There were a number of avenues by which an aspiring officer could obtain his first commission: either by purchase or by obtaining a free vacancy. For most of the 18th century the regimental agent provided the first point of contact, although from 1793 onwards, direct application could be made to the Commander-in-Chief of the regiment. In many cases these applications and any accompanying testimonials as to the young man’s fitness to serve his King were endorsed or even written by commanding officers. However, where there was no such recommendation, the applicants tended to be offered commissions in colonial formations such as 2/60th on Antigua, or in one of the West India regiments.

A typical example came from Lieutenant James O’Neil of the 94th Foot, writing to the Duke of York on 16 December 1795: ‘Memorialist has had the honour to serve 19 years a Subaltern and purchased his first Commission and is now the oldest Lieutenant in the Service. That your Memorialist is not able to purchase a promotion having a Family of 5 Children, two of them Sons able to Serve. One of whom, James O’Neil, he has fitted out at an inconvenient Expence. And he is gone a Volunteer with the present Expedition to the West Indies. Your Memorialist could not afford to fit out his second son Arthur as a Volunteer on an uncertainty, And has some hopes that Sir Ralph Abercrombie may Notice his son James on service. Your Memorialist as an old officer with a heavy family and no mode of providing for them humbly prays your Royal Highness will please to recommend his two sons to His Majesty for Ensigns Commissions, or please to recommend himself for a Company on any service.’

Sir John Cradock: Cornet 4th Horse 1777, Ensign 2nd Footguards 1779, Lieutenant and Captain 1781. Major 12th Dragoons 1785, Major 13th Foot 1786, Lieutenant-colonel 16 June 1789. Served in West Indies under Grey in command of 2/Grenadiers, Colonel 127th Foot 16 April 1795 – reduced. Colonel 2/54th – reduced. Major-General 1 January 1797. Served on staff in Mediterranean and Egypt 1801, then Corsica, Madras and Portugal. Colonel 23rd Fusiliers 2 January 1809.

This particular appeal was partly successful in that both sons were appointed ensigns in 4/60th as of 16 December, but although O’Neil himself went to the 22nd Foot in consequence of the reduction of the 94th, he does not appear in the 1797 Army List.

Generally speaking however the colonel’s backing was crucial in obtaining a commission, particularly as he also had the right to approve any applications to purchase vacant commissions.

While all three King Georges were opposed to the purchase of commissions no realistic, or at least acceptable, alternative had presented itself during the 18th century. The Army is often criticised for giving no serious consideration to introducing a system of regimental promotions based entirely on merit. While this might appear surprising, there were in fact widespread political as well as professional objections to any proposals of this nature, since it was considered that regimental promotion would then come to depend upon patronage. In fact, although the gentlemen of the Navy pointedly looked down on the alleged lack of professionalism in the Army, the professional examinations, or vivas which supposedly governed promotion in that service were wholly concerned with the unique skills associated with ship-handling and maritime navigation. Once a candidate had successfully ‘passed’ as a lieutenant his subsequent career depended entirely on seniority and patronage.

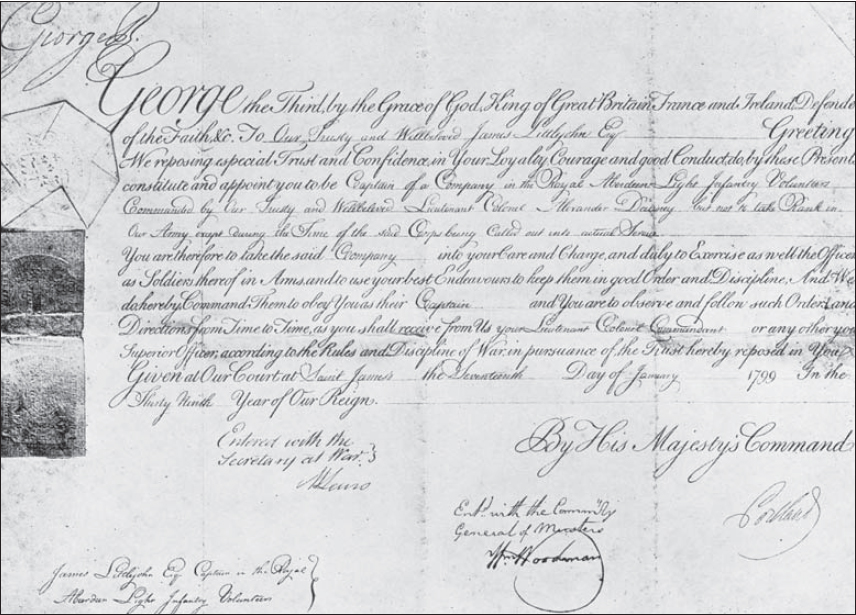

The King’s commission; all officers derived their authority and accounted their seniority from this all-important document. This particular example is made out in favour of James Littlejohn Esq., a captain in the Royal Aberdeen Light Infantry Volunteers. Exactly the same form (printed in a cursive typeface) was used for regular commissions.

In order to purchase a commission a young gentleman had first to obtain the approval of the regimental colonel, then deposit the required sum of money with the relevant regimental agent. The colonel, or more commonly the agent acting on his behalf, would then forward the applicant’s name and any letters of recommendation to the Adjutant General’s office at the Horse Guards for approval by the Commander-in-Chief. This was normally a formality and once the initial commission had been obtained, subsequent steps could be purchased in exactly the same manner. The colonel would request that the officer in question be allowed to purchase the desired promotion or exchange with a named officer in another unit. If a particularly ambitious officer could find no vacancy in his own regiment, the agent could always be relied upon to find one in another of the regiments in his ‘management portfolio’.

Throughout most of the 18th century there was an officially regulated price for commissions. In peacetime – and to a rather more limited extent in wartime – it was also customary to smooth progress by paying something more on top, but for the meantime it is important to appreciate that the regulated price represented what might be termed the absolute value of a particular commission, not the sum which actually changed hands.

This requires some explanation. In the 1790s the regulation price of an ensign’s commission in an infantry regiment was £400, and leaving aside the usual fees and anything else which might be clandestinely agreed, this is exactly what it cost him. A lieutenant’s commission was valued at £500, but all that actually changed hands in purchasing it was the ‘difference’ of £100 and similarly with a captain’s commission valued at £1,500, a lieutenant who wished to buy his way up only had to find the difference of £1,000. Should he then decide to realise his investment by selling out, the £1,500 was made up by reversing the process. That was what he was paid by the three officers benefiting from his departure. His immediate successor paid him £1,000 for his captaincy, another £100 came from the ensign moving up into the lieutenant’s place, and the balance came from the young gentleman paying the full price for the ensigncy. Although at first sight the process might appear cumbersome it was actually quite straightforward since all the paperwork and cash transactions were normally handled by the regimental agent.

Although purchase might justifiably be regarded as the mainspring of the promotion system, seniority also played a very considerable part in determining how an officer’s career progressed. It was the sole regulating factor in both the Ordnance and East India Company service, but its importance in the King’s service should not be overlooked. For instance, if an officer died the senior man in the grade below obtained the vacancy without payment and everyone else shuffled up behind him until eventually a free vacancy was created for a new ensign. Free vacancies also arose when an officer was dismissed from the service by the sentence of a court-martial. In this case however it was an invariable rule that the cashiered officer would be replaced by a man brought in from outside the regiment in order to avoid any suggestion that his colleagues might gain from convicting him. In addition, when a commission did become vacant by purchase it was the senior man who had the right of first refusal.

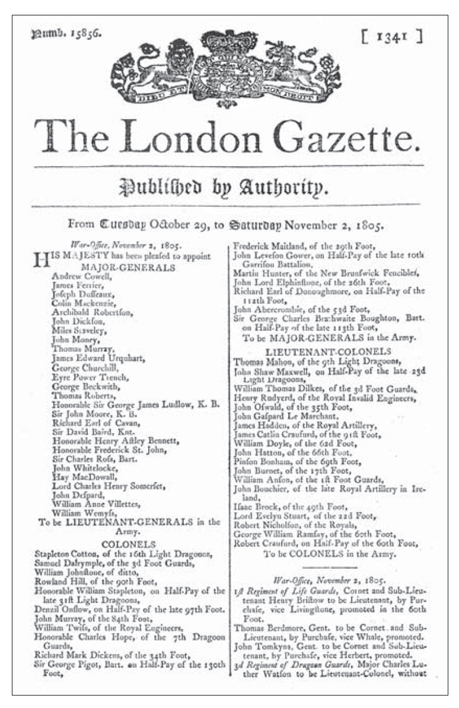

The London Gazette: officers’ commissions and appointments were officially announced in this weekly journal; hence the term ‘gazetted’.

However, it was not always as straightforward as it might at first appear. An officer’s seniority in the army was primarily determined by the date of his commission as it appeared in the official Army List. Ordinarily this also determined his standing within his regiment, but it was quite possible for Army and Regimental seniority to be at variance. Any difference was obvious when an officer exchanged from one regiment into another or joined from the half-pay (which was particularly common in newly raised battalions). His regimental seniority would then be accounted from the date on which he transferred, but his Army rank (other than by brevet – a military commission entitling an officer to take the rank above that for which he receives pay) was still calculated according to the date of his original commission.

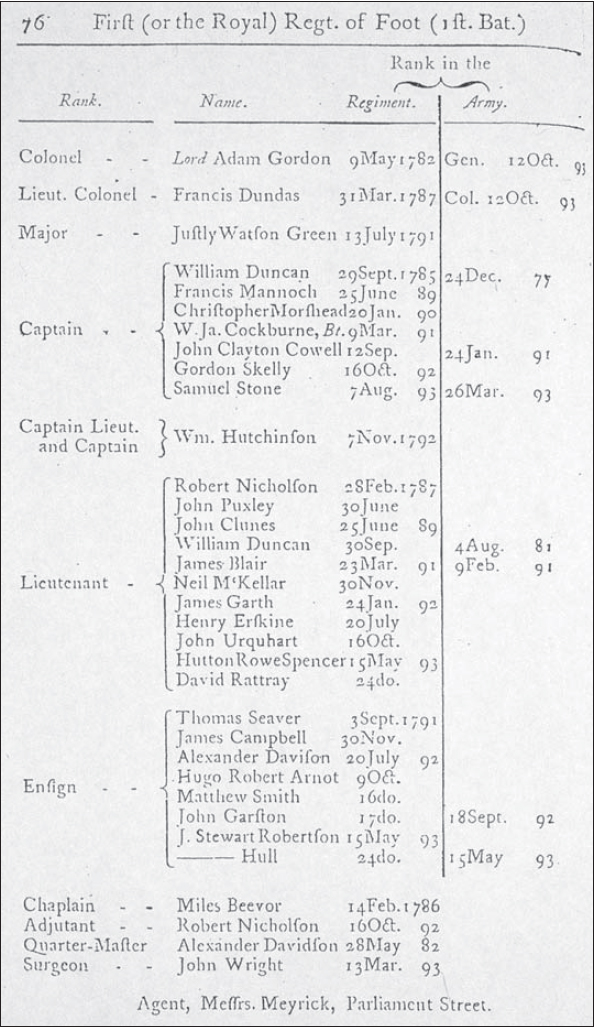

Officers’ seniority was recorded in the annual Army List. In this extract from the 1794 edition officers of 1/1st (Royal) Regiment are listed by their regimental commission dates in their respective ranks. The column on the right however records the original date on which an officer reached that rank in the army, either by brevet or when serving in another unit.

It was therefore possible for an officer to jump the ‘queue’, since although he might then be at the bottom of the list regimentally, he could still be the most senior man by commission date and was therefore entitled to claim the next available purchase vacancy. Vacancies brought about by death, however, were almost always filled strictly according to regimental seniority.

On being appointed Commander in Chief in 1795 the Duke of York insisted that no officer could become a captain without at least two years’ service, or a field officer without six. There had been attempts to impose qualifying periods before, but this time they were pretty strictly enforced. Consequently the old complaint that it was possible for a schoolboy to purchase his way up to lieutenant-colonel in a mere three weeks was firmly addressed. On the other hand it was quite possible to have a situation where those officers who had the necessary qualifying experience lacked the cash to purchase and those further down the List had the cash but not the experience. Therefore, if there were no takers within the regiment there was nothing to prevent a suitably qualified outsider buying his way in to the regiment, either directly or by first exchanging with one of the disappointed. This seems to have occurred more frequently in promotions to field rank where both the ‘difference’ and the service qualification were substantially greater than at company level.

Before leaving the subject of seniority, one further aspect needs to be noted. Up until the early 1800s most infantry regiments had just one battalion, and in those few which did have more than one, such as the 1st (Royal) and 60th, the officers belonging to each battalion were listed independently and in effect were entirely separate corps.

In the expansion of the Army, which followed the collapse of the Peace of Amiens in 1803, all that changed and by 1814 all but a handful had two battalions, or sometimes more. This time the Army List made no distinction between them and listed all the officers belonging to a particular corps in a single sequence. In theory the more senior half of the officers in each grade served with the first battalion while the juniors served with the second. Consequently any promotion invariably led to an exchange of officers between the two. On being promoted a lieutenant serving with the first battalion became his regiment’s junior captain and was automatically posted home to the second battalion. In practice however he normally waited until the most senior captain who had been serving in the second battalion came out to replace him. Depending upon a variety of circumstances he could wait for some time, or conversely, if it was quiet enough at the front, simply take himself off home without waiting.

On the whole this was an excellent system which helped to ensure that the second battalions were properly provided with some experienced officers – particularly as the original intention to reserve them for home defence was soon abandoned. However, there was an unfortunate end to the system in 1814 when the additional battalions were disbanded and their officers placed on half-pay according to regimental, rather than Army, seniority.

Despite an almost universal objection to a regimental promotion system based on selection (or patronage), promotion by merit did in fact take place not just in the recommending of deserving candidates for commissions, but also, to a limited extent, in the form of brevets.

Although a civilian, the agent played a vital part in the management of a regiment. This is perhaps the most famous of them all, ‘Honest Jack’ Calcraft (1726–72).

Ensigns and lieutenants were not eligible to receive brevets, but otherwise almost any officer could receive a promotion by brevet under a variety of circumstances. These could sometimes be quite indiscriminate, as in the case of the ‘victory’ brevet of 1814, which advanced all those officers whose commissions dated to before the outbreak of war in 1803. Local brevets were also granted to East India Company officers in order to place them on the same footing as Royal officers serving east of the Cape of Good Hope. Otherwise brevets were normally given to individual officers either by way of a reward for some exceptional service, to confer local seniority within a specified geographical area, or to lend added authority to a staff appointment. Promotion by this means could be incremental and it was quite possible for an officer to be a lieutenant-colonel or even a lieutenant-general by brevet while still holding the regimental rank of captain.