Whether wearing the King’s red coat or an old slouch greatcoat, an infantry officer’s normal duties fell into four basic categories. He was expected to lead his men to glory in times of war, of course, but stirring deeds which won the empire actually accounted for very little of his time. James Urquhart of the 14th Foot was involved in bush fighting on St. Vincent in 1772–73, fought at Bunker Hill in 1775, and again on board ship at the Saintes in 1782. Allowing an estimated five days for his ‘several actions with the Caraibs’ on St. Vincent this equates to a consolidated total of just one week’s fighting in a career which spanned 40 years. Depending on a variety of factors some officers could naturally notch up rather more combat time, or conversely see out their whole career on garrison duty with never a shot heard fired in anger, but the inescapable conclusion is that even allowing for the associated time required to march to and from the battlefield, and waiting around for something to happen, fighting occupied only a very small element of an officer’s time.

In peacetime he could all too often be required to give aid to the civil power. This was always a hazardous duty, demanding a considerable degree of personal initiative (often on the part of quite junior officers), and certainly required sufficient force of character to stand up to the local authorities as well as to whoever was committing a breach of the peace, riot or tumult. An officer could well find himself aiding the revenue service in combating smuggling or illicit distilling (especially in Scotland). In both cases he had to take great care to operate strictly within the letter of the law, for otherwise it was all too easy to be prosecuted for the actions of his men. Hunting for illicit stills was also a particularly thankless task since, as the commander of a lonely detachment of the 13th Foot stationed at Braemar Castle lamented, the soldiers themselves were often the distillers’ best customers. In Scotland, for a fair part of the 18th century, officers were also employed in supervising work parties on the military roads and, although this could be a lonely duty, it brought officers and men together in a way which may not have been possible in a more tightly disciplined environment.

Another major job on which officers were employed was the recruiting service. This was an extremely unpopular duty as far as most officers were concerned, and perhaps for that reason it was very common to employ newly commissioned subalterns on this service. Unfortunately, entrusting youngsters with large sums of money, far away from proper supervision, could have unhappy results. In Advice to Officers sergeants were cynically recommended that ‘If you have a knack at recruiting, and can get sent on that service with an extravagant young subaltern, your fortune is made; as the more he runs out, the more you ought to get … Nor need you fear anything from his future resentment in case of a discovery; as it is ten to one but the consequences of six months recruiting will oblige him to sell out, and quit the regiment for ever.’

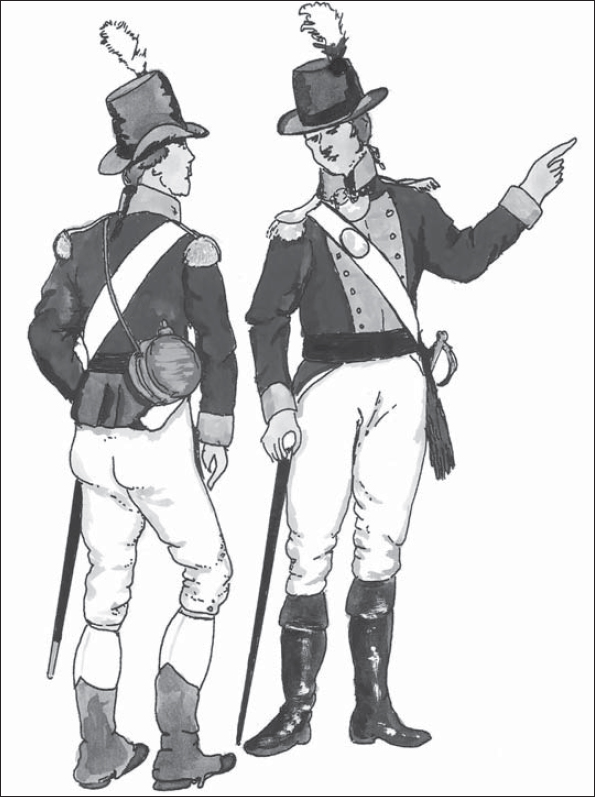

Major John Andre, Sir William Howe’s Adjutant General, after a self-portrait.

Even if dishonest sergeants and the temptations of the flesh were avoided, the recruiting service itself was not without its financial perils. While the sergeant and his assistants were directly concerned in bringing in the recruit, should he then desert en route to headquarters, or be rejected by either the commanding officer or an inspecting field officer on arrival, the recruiting officer was held responsible for any monies already laid out for his bounty, entertainment, lodgings and attestation fees. In addition he was also responsible for the advertisements and any other costs incurred in pursuing a deserter, and equally cripplingly, for the costs of sending a rejected man home again. It was little wonder therefore that the Duke of Cumberland preferred that only experienced officers should be sent out recruiting, or that if subalterns were employed they should do so under the supervision of a more senior officer, placed in overall charge of the ‘recruiting service’.

Such supervision also ensured that unscrupulous young men did not misappropriate the money entrusted to them too blatantly. There is a shrewd suspicion, however, that one reason for sending newly commissioned ex-rankers out on the service was to allow them the opportunity to misapply those funds to the purchase of their kit.

Financial pitfalls were also to be encountered in the officer’s primary area of responsibility, which was the administration of his company or battalion. Once again this clearly entailed the more obvious duties such as ensuring that his men were properly clothed, fed and accommodated, trained and disciplined (either personally or informally, or by sitting on courts-martial and courts of inquiry). At a more mundane, but no less important level, the captain of a company also acted as its paymaster and banker. Some idea of what this entailed, both in terms of the workload and its costs, may be found in a contemporary ‘computation’ of the yearly expenses of an infantry company which included: ‘Charges attending Musters, writing Muster Rolls etc.; Expense of burying Men; Charge of sending after and taking Deserters, and advertizing Deserters; nursing Men and extraordinary expenses in fluxing Men, etc.; and the Expenses of carriage of Gunpowder from ye places ye warrants upon etc. to ye Company Quarters.’ Together with other miscellaneous charges such as ‘printing Furlows and Discharges’ and buying twice-weekly copies of the Gazette, this came to £11 19s 8d per annum in 1727, which, ominously, exceeded the allowance for the purpose by seven shillings. Of itself this might not appear crippling, but in practice it could turn out to be very much higher, especially as prices rose significantly during the course of the 18th century without a corresponding increase in pay scales.

Far from being rich men, all too many Georgian officers found their income wholly inadequate to the task of supporting the lifestyle expected of a gentleman. As Ensign Thomas Erskine of 1st (Royal) complained at length: ‘Officers in the army, even in the most subaltern grades, have the misfortune to be considered as gentlemen which in England, as in other countries, implies a denomination of persons who from accidental circumstances of office or property are divided from the common herd of mankind and are obliged to form a barrier between those two orders, by the luxuries of dress, equippage and attendance, but as the superfluities of life are the only props to this order of society, it is evident how distressing it must be to be installed in it unfurnished with the very article to which it owes its existence.’

Officers of the 61st Foot in Egypt 1801 after Private W. Porter of that regiment. The wearing of round hats is unexceptional, but the grenadier officer, identified by his all-white hackle, is wearing a jacket rather than a coat – perhaps the single – breasted one officially abolished in 1798. Unfortunately it is not possible to see whether the field officer is wearing a coat or a jacket, although his lapels are buttoned back to display the regiment’s buff facings.

An ensign’s annual pay and subsistence amounted to a princely £66 18s 4d in the 1760s. Captain Thomas Simes reckoned his ‘constant expenses’ for breakfast, dinner, wine, beer, laundry, consumables (such as pens, paper, ink and so on), as well as the services of a soldier to dress his hair and shave him, were £46 11s 8d, which left precious little margin for error, let alone the purchase of any new clothing or equipment. Nor did matters improve for the higher ranks. In 1749 Lieutenant-colonel Samuel Bagshawe itemised his annual expenditure, including buying clothing, keeping the two horses which his rank required, and various other outgoings, and rather gloomily concluded that his expenses exceeded his income of £280 17s 1d by £104 5s 7½ d. Significantly those expenses included interest payments of £73 2s 6d on £1,350 borrowed for the purchase of his commissions.

Interestingly enough Sam Bagshawe also related that; ‘The method of an officer’s diet in general is breakfast at his own lodging, dinner and supper in a tavern. I will suppose his breakfast 6d, dinner 13 pence, supper and different kinds of drinkables one day with another two shillings and sixpence.’ Bagshawe’s account suggests that he tended to dine alone, which was certainly the experience of most officers as far as breakfast was concerned, but it was much more common for the unmarried officers to mess together for dinner or supper.

In 1809 a newly commissioned Ensign Keep of the 77th Foot, in barracks at Winchester, wrote a superb description of a regimental mess: ‘One long table accommodates us all, with about 15 officers on each side with a president at one end, and a deputy at the other. The furniture of the table is entirely (like the band instruments) the property of the officers, and by continual contributions is very sumptuous (the Paymaster has deducted from my pay for this purpose £6 10s 0d). Grand silver chandeliers and choice plate with all the other things necessary are provided by this means … We pay 2s 3d each for our dinner, which consists of three courses well supplied, but no dessert except when we have company. It is the only meal we take together; each officer provides himself with his own breakfast things and bedding, both of them are therefore required to be as portable as possible. Tables and chairs and coals and candles are supplied by the Barrack Master. Each Saturday night we give a card party and supper to the married officers and their ladies, and on other occasions the Mess room with newspapers is always open.’

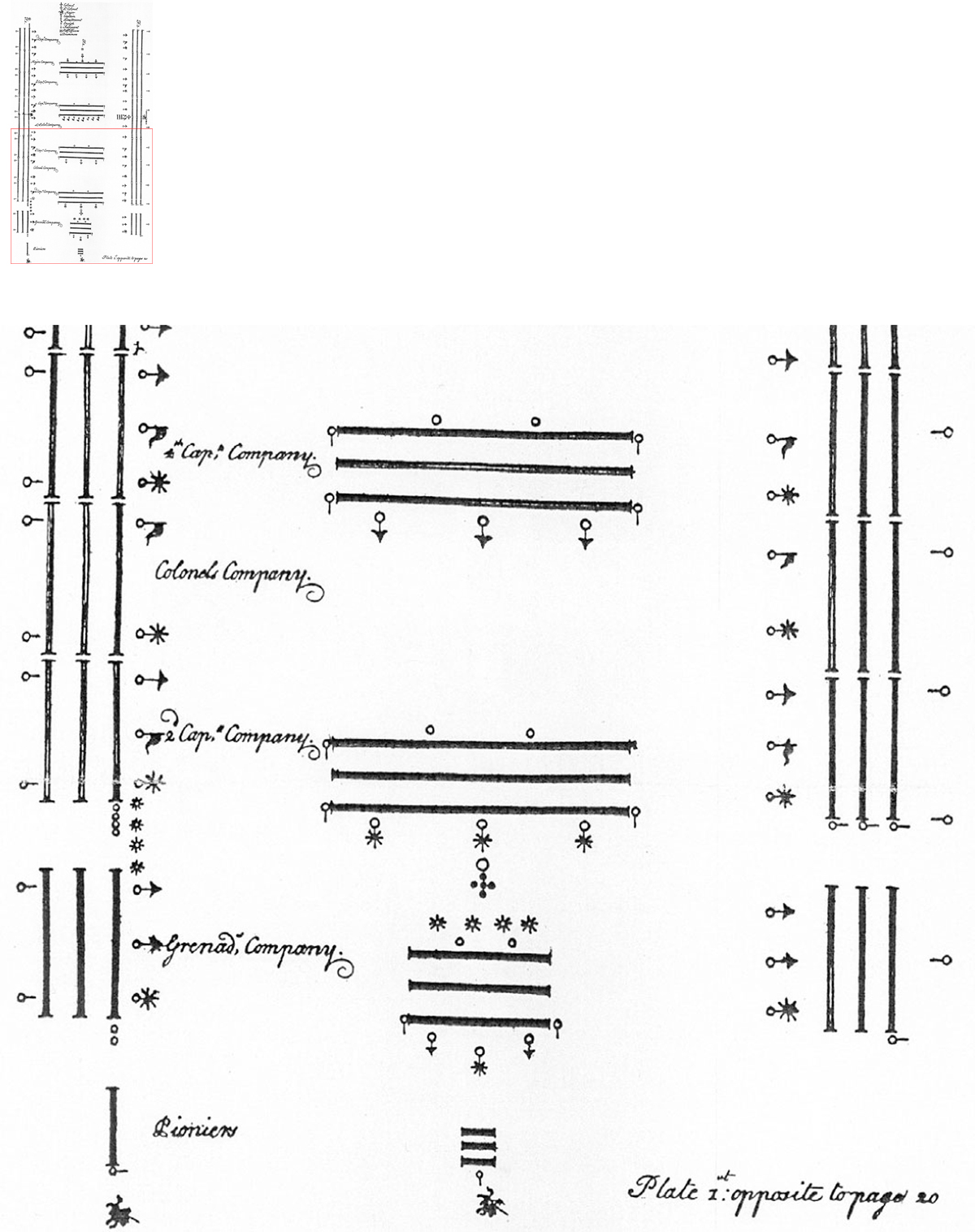

Battalion deployment according to the 1764 Regulations. Note that at this time the captain stood on the right of the company, the lieutenant on the left and the ensign in the centre; except for the three field officers’ companies which paraded only a lieutenant and an ensign.

Although they tended to mess together whenever practical, prior to the move into barracks at the end of the 18th century (and even afterwards) officers lived, as far as possible, in individual lodgings or billets, especially if they were married. In peacetime, or at least in relatively settled conditions, an officer was generally expected to make his own accommodation arrangements, and received a small allowance for the purpose. However, when on active service he received a billet or order from the local town major or commissary allocating him a room – or a whole house if he were of sufficiently exalted rank.

The accepted rule was that two subalterns should share, while captains got a room or a tent to themselves. In New York on 22 February 1759, the officers of the 42nd Highlanders were advised that: ‘No more than one tent will be Allowd for two subalterns, they are therefore to divide themselves and bespeak their tents accordingly as none is to be bespoke for them.’ Ensign Keep was less than impressed by this when he was posted to the barracks at Berry Head in November 1811: ‘Great inconvenience arises from this arrangement – two bedsteads to be put up, dressing tables, writing tables, breakfast apparatus etc, and it is necessary that the inmates should act in thorough good accordance with each other’s wishes, and be thorough good friends, to go on comfortably, in such close approximation together.’

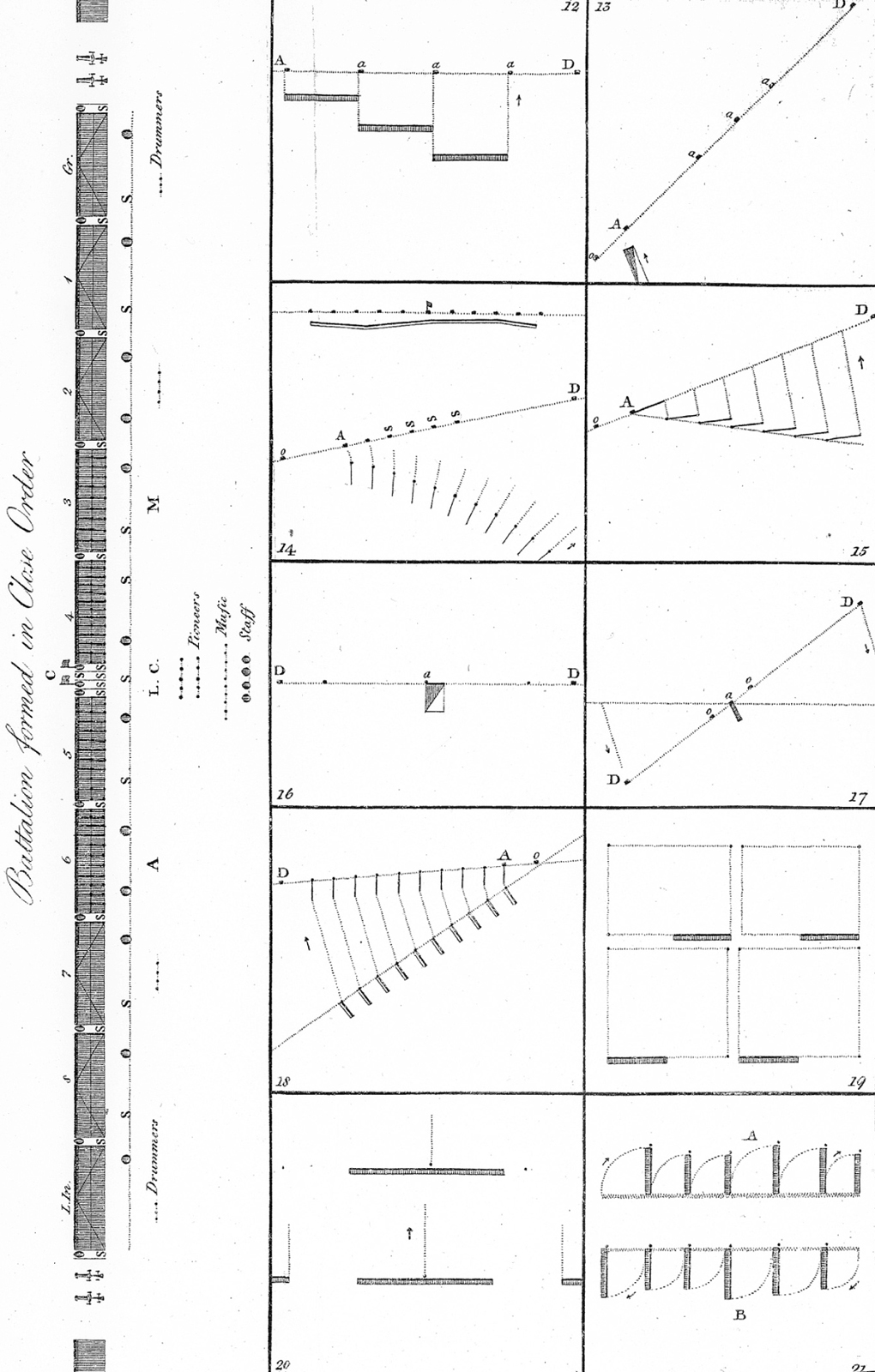

Plate 2 from the 1792 Regulations depicting a battalion formed in close order on parade; the commanding officer is identified by the letter C, the lieutenant-colonel by L/C., the major and adjutant by M and A respectively, and the company officers by O. The four staff officers in rear of the ‘Music’ are the chaplain, surgeon, quartermaster and surgeon’s mate.

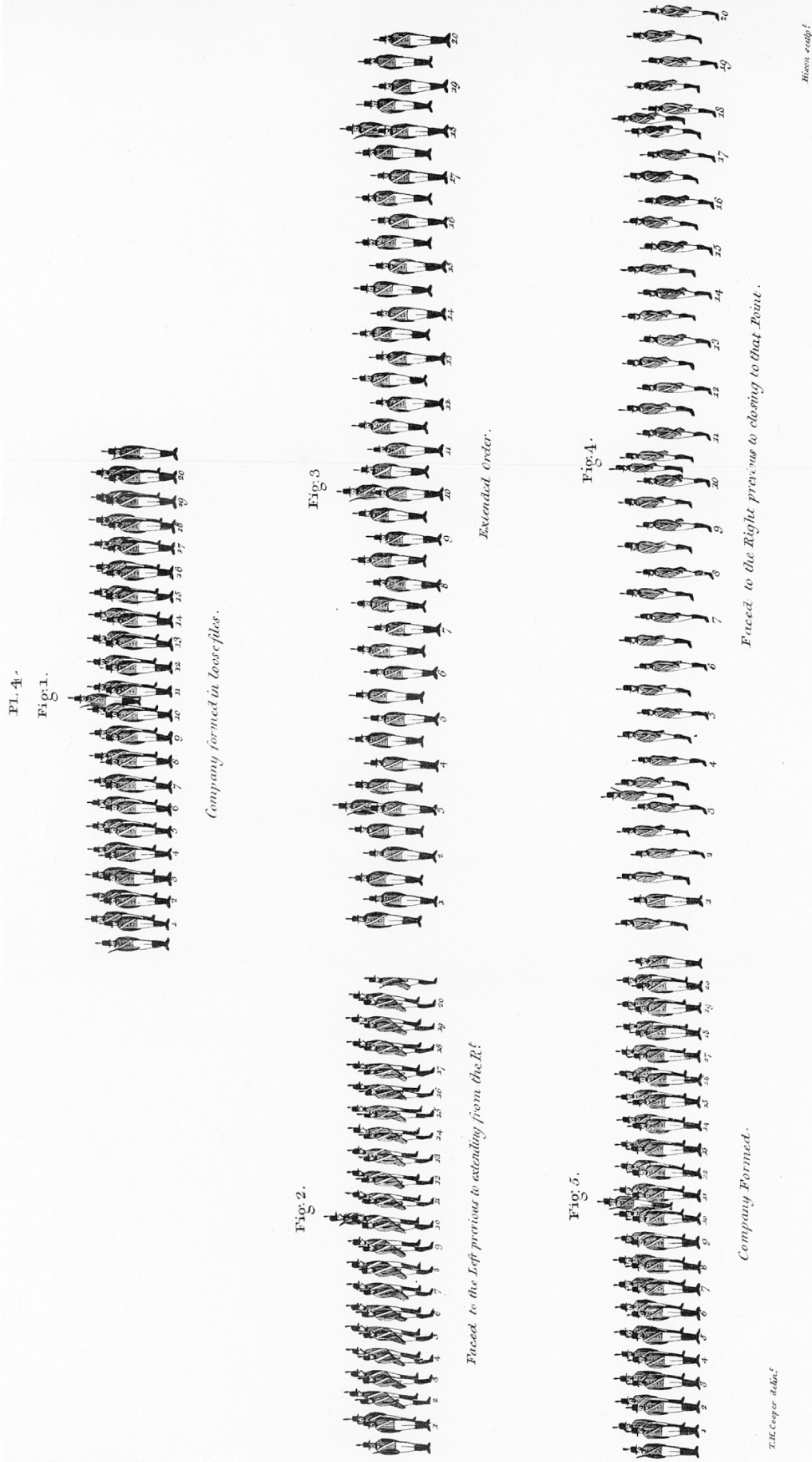

Deployment of a light infantry company as depicted by Captain T. H. Cooper. Note the positioning of the officers.