Since Britain is an island, it was inevitable that an officer’s campaigning experience commenced and, hopefully, ended with a sea voyage of some description. Conditions on board ship naturally varied enormously, but there was general agreement that the most comfortable were chartered East Indiamen and West Indiamen or, in peacetime, stripped-out warships, since both were considerably roomier than ordinary merchantmen.

While the rank and file were normally accommodated in the hold, officers had cabins, although they were by no means luxurious. Lieutenant Frederick Mackenzie of the 23rd Fuziliers recorded that his wife Nancy, their two children, together with Lieutenant Gibbons’ wife, her child and a maid, shared a cabin measuring 7 feet by 7 feet, when the regiment sailed for New York in 1773. Even this miserable space sometimes had to be paid for. When the 79th (Liverpool) Regiment was embarked on West Indiamen for Jamaica in 1779, it was at first proposed that the officers should each pay £30 for their berths. Not surprisingly they maintained that they could not afford what were commercial rates, and flatly refused to embark, but in the end an ‘Accomadation’ [sic] was reached whereby the shipmasters settled for £25, of which £5 was paid by the officers and the balance by the Navy’s Transport Board. In addition to this basic charge, whether they were carried on hired transports or on naval vessels, officers had to lay in their own ‘sea stock’ to supplement the basic ‘victuals’ provided by the purser. Lieutenant Mackenzie and the other officers on board the Friendship chipped in £10 a head for single men and £15 for married ones, irrespective of rank – an advance of pay was usually provided for the purpose – and as a consequence ‘lived exceeding well, and hardly eat any Salt provisions’.

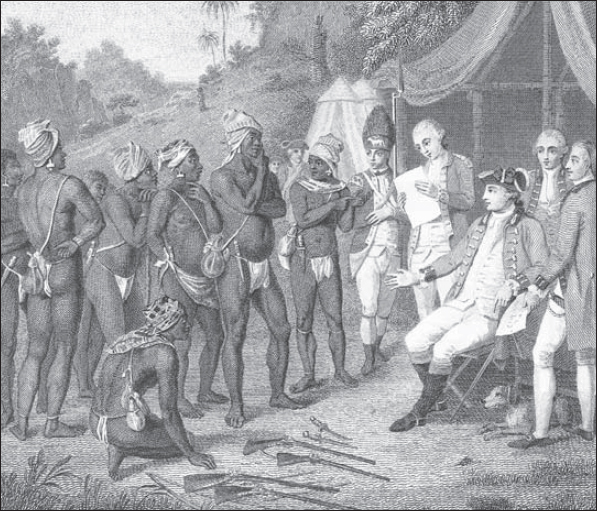

Pacification with the Maroon Negroes, Jamaica 1796, taken from a contemporary sketch and showing few concessions to the climate, although General Balcarres is for some reason wearing an aid de camp’s embroidered coat, perhaps because his own undress coat was insufficiently grand for the occasion.

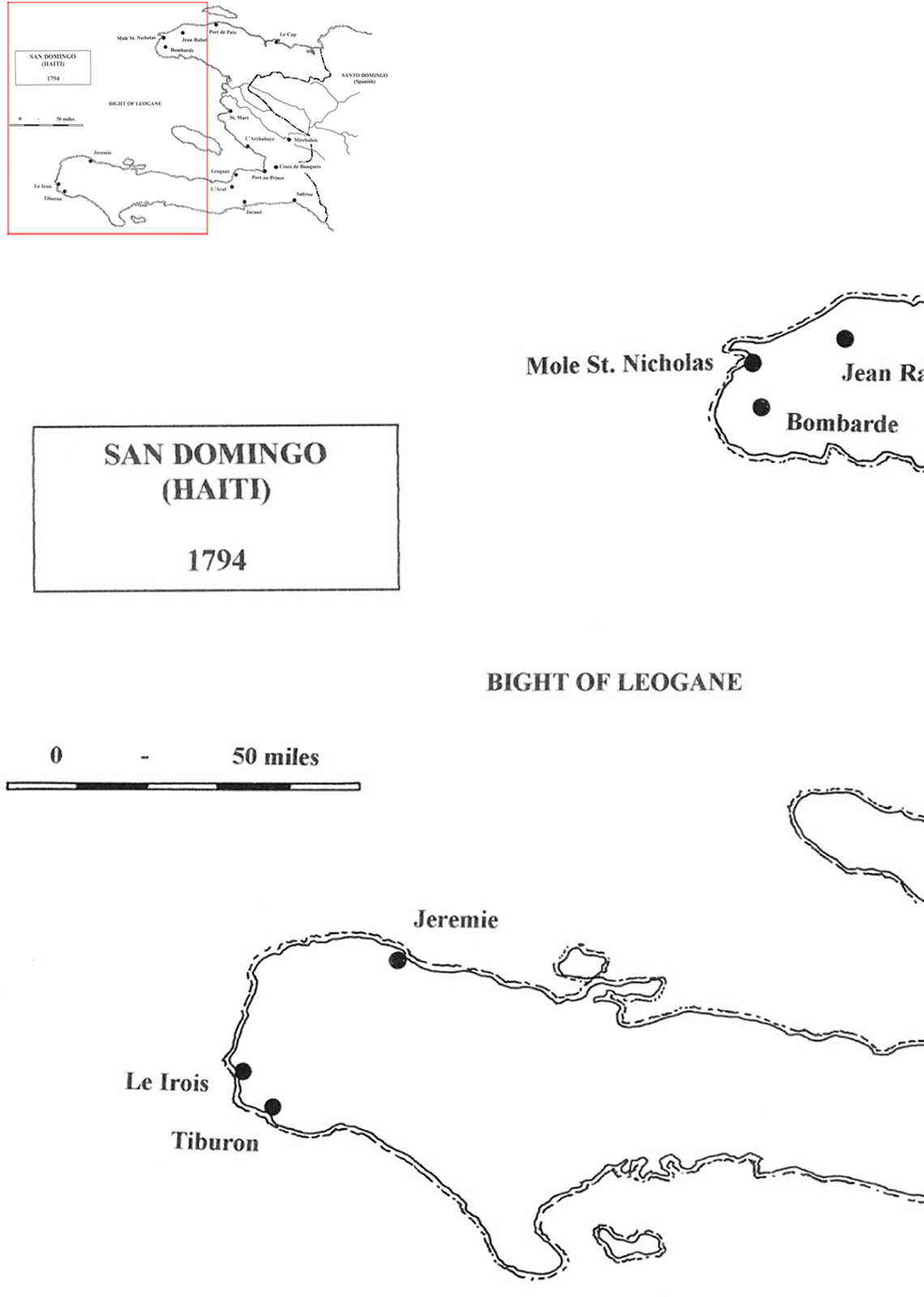

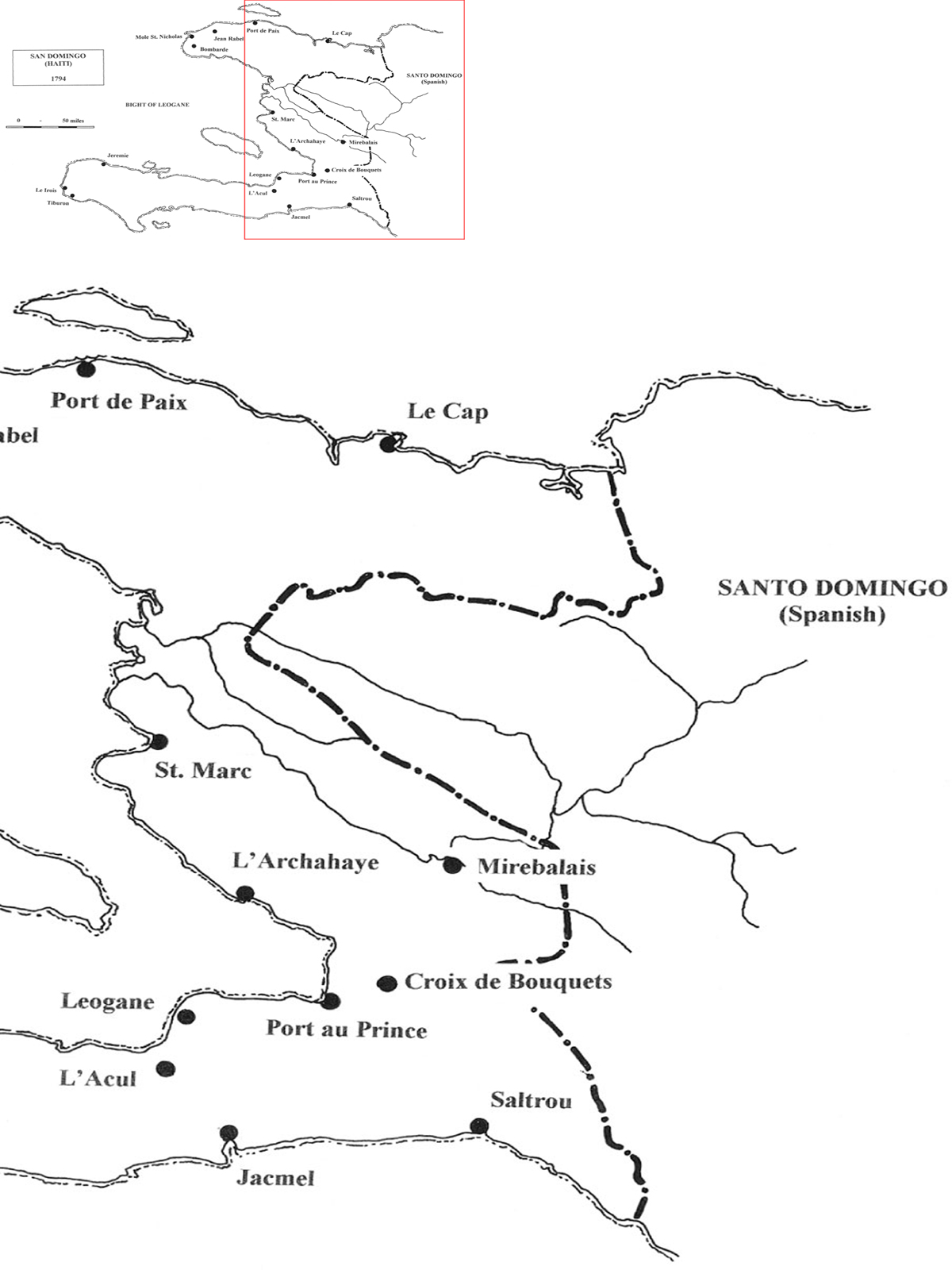

Map of St. Domingo; the principal British garrisons were at Port au Prince, the Mole St. Nicholas, Archahaye, Leogane and Jeremie. A notable feature of the campaign on St. Domingo was the extent to which very junior officers were left to conduct military operations on their own initiative and develop a sense of self-reliance.

Whether jammed together or not, an officer’s lifestyle at home or at least in peacetime could be agreeable enough, but foreign billets often proved a grave disappointment, though it was hardly to be expected that they should invariably be welcomed with open arms.

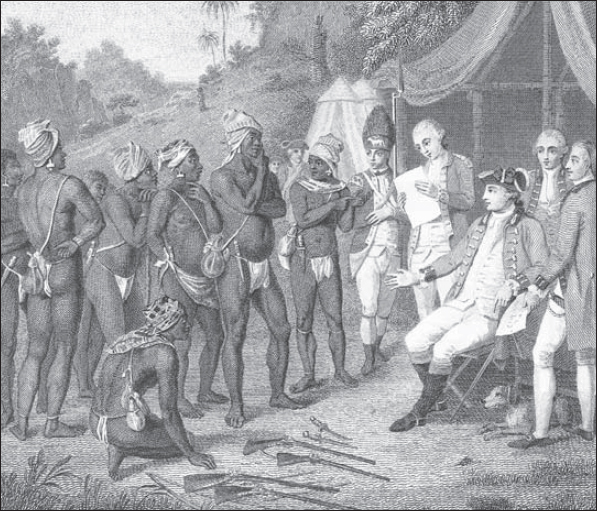

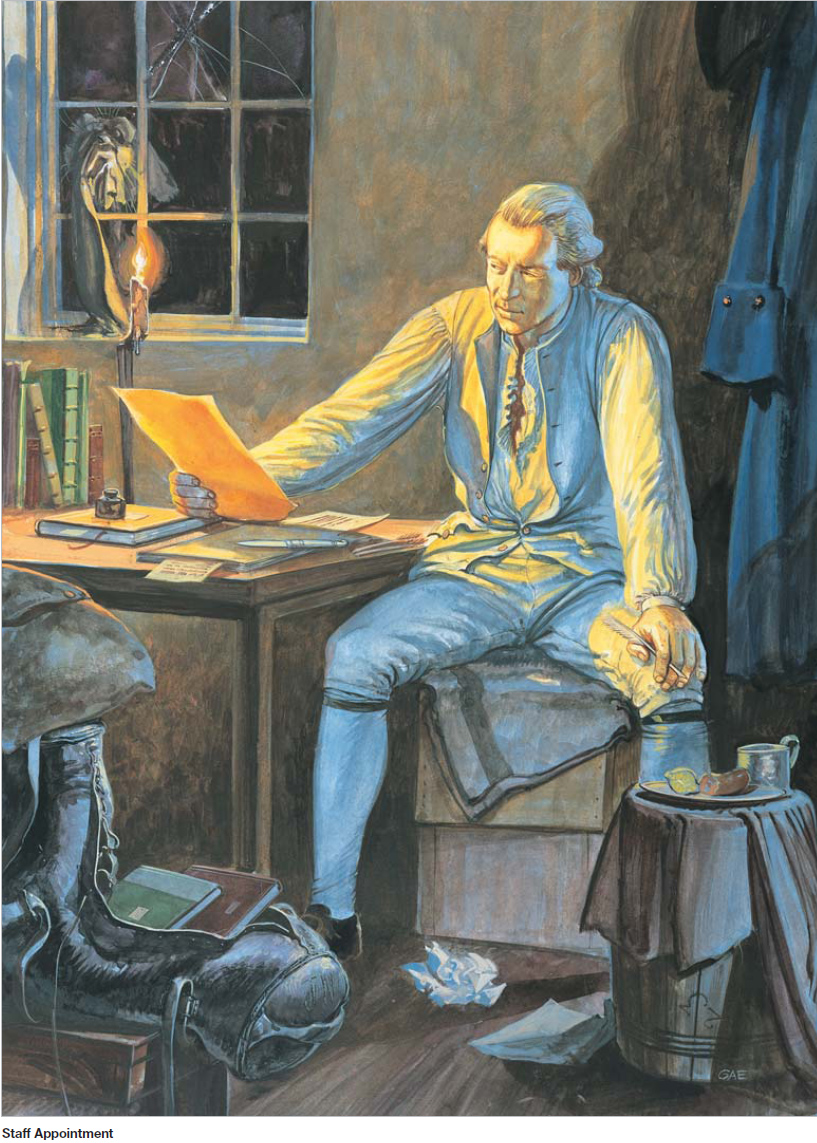

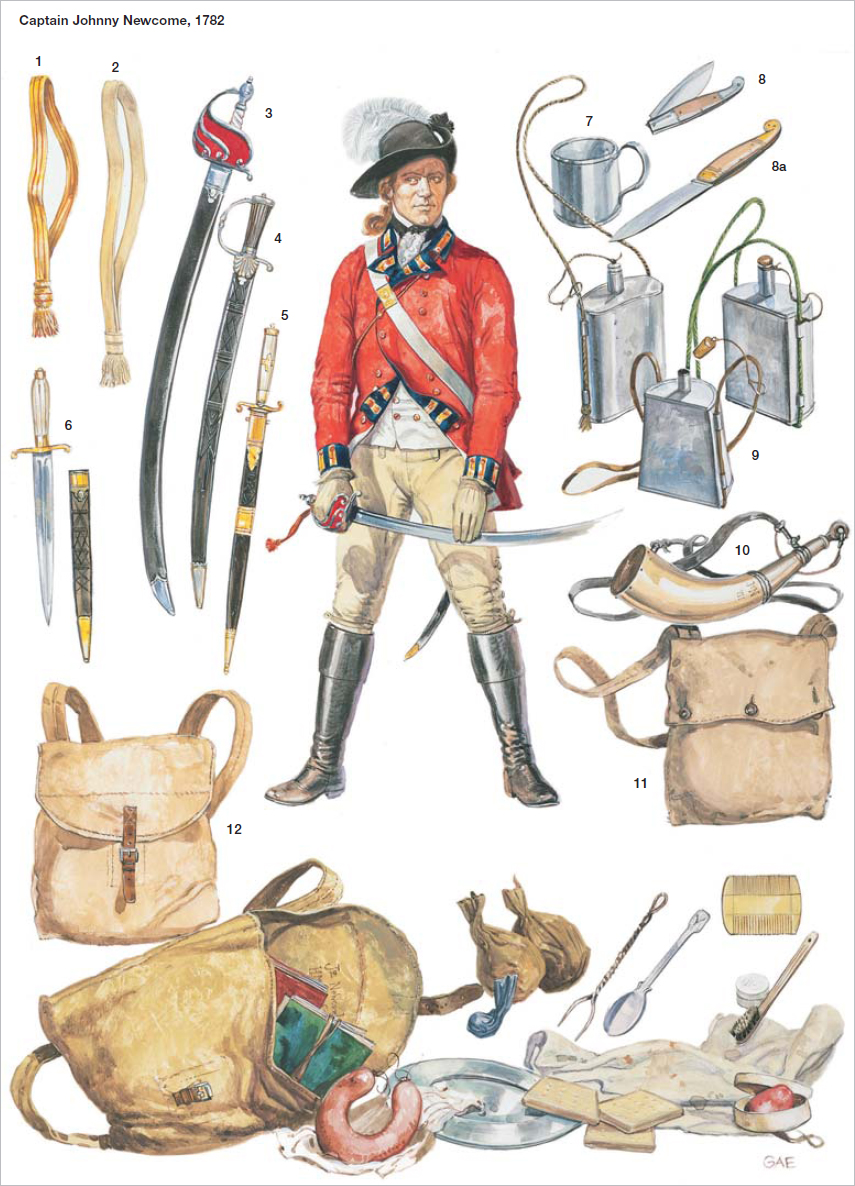

The rigours of campaigning were of course compounded by having to travel light; on receiving his marching orders, most of an officer’s kit had to be packed away and left in storage. On 22 May 1778, John Peebles packed up his baggage and ‘made an assortment for the Field. 2 Coats 8 Shirts washing breetches & waist coats, trouzers’. When bound for Walcheren in 1809, Ensign Keep, then of the 77th, wrote: ‘We … intend taking our boat cloaks rolled up and fastened to our backs like the soldier’s knapsacks, and carrying our eatables in haversacks etc.’

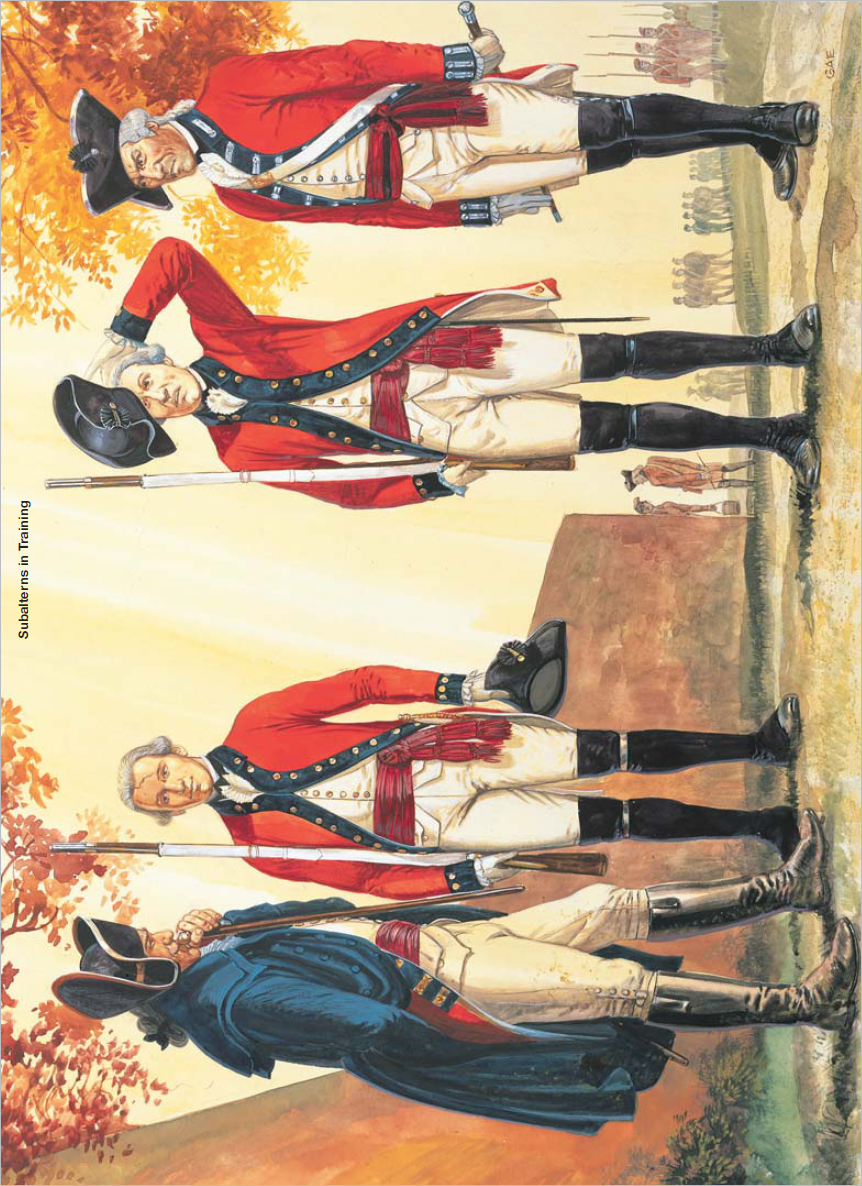

In this particular case the amount of baggage allowed was cut right down to what could be carried on an officer’s own back for operational reasons. Ordinarily officers were allowed a ‘bat’ horse (a bat being a French term for a pack-saddle), which could be led by his soldier-servant or batman. In the 1740s, subalterns were allowed £3 15s to purchase one, regimental staff officers were allowed £5 and captains £7 10s – sufficient for two horses. By 1796 the ‘whole of the personal Baggage of a Subaltern officer’ was officially to be valued at £60 in case of loss, and two subalterns could share another £35 for their camp equippage. A captain on the other hand could claim £80 for his personal kit and another £35 for his camp equippage, while field officers were entitled to £100 and £60 respectively.

Similarly, although only the field officers and adjutant were supposed to be mounted (and could therefore claim for the loss of a horse on active service), it was common for company officers to find themselves at least one riding horse for the march. In addition, many also acquired additional baggage animals, especially if they were married and had dependants of one sort or another.

A surprising number of officers’ wives accompanied them overseas, especially if the posting was expected to be an extended one. There were evidently a fair number in Boston in 1775 for example, which was perhaps only to be expected from what had been a peacetime station. Others followed the army in the field, especially during the Peninsular War, perhaps in part because officers, such as Lieutenant Mackenzie of the 23rd, married much earlier in life than their successors would do during Queen Victoria’s time. Since subalterns found money tight enough at the best of times, there then may have been no alternative but to take their wives campaigning with them, especially as many were young enough and fit enough to regard it as an adventure, as Captain Landman discovered to his cost at Roleia:

‘I overtook a lady dressed in a nankeen riding habit and straw bonnet, and carrying a rather large rush hand basket. The unexpected sight of a respectably dressed woman in such surroundings greatly perplexed me; for the musket shot showering about pretty thickly and making the dust fly on most parts of the road. Moreover at this place, several men were killed, and others mortally wounded, all perfectly stripped, were lying scattered across the road, so that, in order to advance, she was absolutely compelled to step over them. I, therefore, could not resist saying to her, en passant, that she had better go back for a short time, as this was a very unfit place for a lady to be in, and was evidently a very dangerous one. Upon this, she drew herself up, and with a very haughty air, and, seemingly, a perfect contempt for the danger of her situation, she replied, ‘Mind your own affairs, Sir, – I have a husband before me.’