Provision for an officer’s retirement was inextricably linked with purchase. Ordinarily an officer was expected to provide for himself by selling his commissions and purchasing an annuity with the proceeds. If the whole sum was invested it was calculated that an interest rate of 4 percent would produce an annual income equivalent to his pay.

Throughout the 18th century it was firmly been laid down that only those commissions which had been purchased could be sold, but in practice the matter was less straightforward.

If we suppose that after having purchased his ensigncy at the regulation price of £400 an officer succeeded to a death vacancy by reason of a lieutenant’s sudden demise, his subsequent promotion to captain would still only cost him the difference of £1000, and apparently he still expected to gain the full £1,500 when he sold out. This however was by no means a right. In 1812, for example, Major Cocks of the 79th Highlanders entered into a complicated arrangement to buy out Lieutenant-colonel Fulton of the same regiment. In order to expedite matters Cocks agreed to take on the selling of most of the gallant Colonel’s commissions, but not his majority since that had been a free promotion and there was consequently no certainty that he would be allowed to sell it.

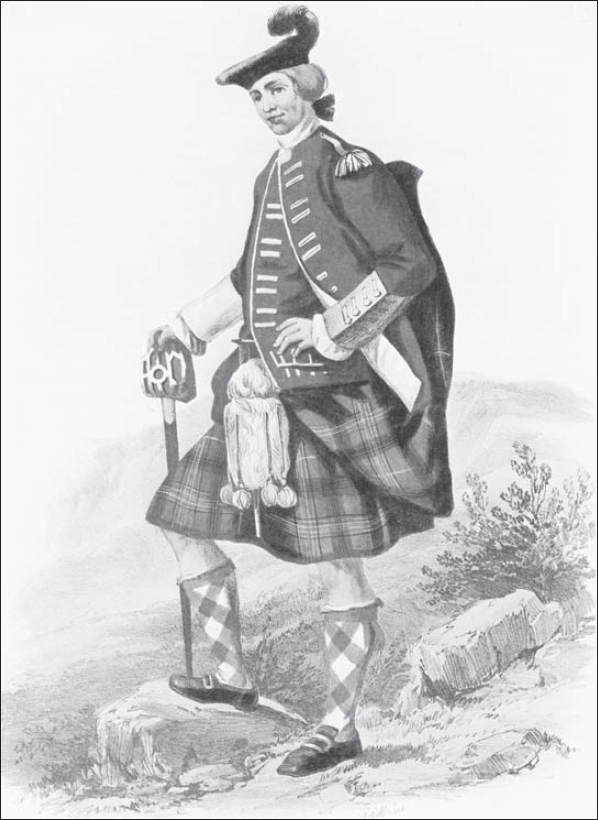

Colonel Sir William Murray Keith, 89th Highlanders; red jacket, dark green facings, gold embroidery. Government set tartan plaid.

On the other hand an ensign who had begun his career with a free commission was in a less happy situation. He would only have needed to pay the ‘difference’ of an easily borrowed £100 to become a lieutenant, and might thereafter have succeeded to a death vacancy as a captain. However, when the time came to retire he had no automatic right to sell the ensigncy or the captaincy and so normally could only expect to receive the ‘difference’ that he had paid for his lieutenant’s commission.

In the circumstances he had two options available to him. The first was to apply through his colonel for permission to sell the free commission(s). Officially this was discouraged since it reduced the number of free vacancies for new entrants, but the privilege was granted in exceptional circumstances. A much more common alternative was to obtain an appointment to a Veteran Battalion, or to retire on half-pay.

The half-pay establishment was made up of phantom regiments and companies disbanded at the end of each war throughout the course of the 18th century. Originally half-pay was provided for the officers of those regiments since they would clearly be unable to find anyone to buy their commissions. In return they were expected to return to the full pay if so required and this actually occurred with surprising frequency. The Government was always anxious to keep the bill as low as possible and whenever a new levy was ordered it was piously expected that as many officers as possible should be drawn from the half-pay. This resulted in a two-way traffic. In the first place an officer who intended to retire as a consequence of wounds, ill-health or old age, but who was unable to sell his commissions could be appointed to one of the many vacancies in the half-pay regiments. This was a relatively straightforward matter and considered to be well worth the additional burden which it placed on the exchequer since the officer’s departure created a free vacancy in his original corps. Alternatively he could exchange with a half-pay officer who wished to return to active duty.

Such exchanges were, as usual, effected through the ever-obliging medium of the regimental agent and were by no means confined to those officers who wished to retire from the service permanently. Those officers who joined the Staff were normally required to ‘retire’ on to the half-pay for the duration of their appointment, while others might choose to do so in consequence of prolonged ill-health or for other personal reasons. Retiring can in fact be something of a misnomer, for while many officers did indeed put their feet up and see out their declining years on the pension, others continued to lead active careers either on the Staff or elsewhere.

In theory too a half-pay officer could be recalled to service at any time – and indeed many were called up during the Irish emergency in 1798 – so a number of conditions were laid down. Half-pay officers could not for example be in Holy Orders and while there was no bar on an officer living abroad, he could not take service with a foreign army. Oddly enough however this did not apply to the East India Company’s armies. John Urquhart, who served as an Assistant Military Secretary at India House in the early 1800s, drew half-pay as a captain in the Royal Glasgow Regiment at the same time, while a contemporary, John Blakiston of the EIC Engineers, was also on the half-pay of Fraser’s long disbanded 71st Highlanders.

When an officer exchanged with another on to the half-pay it was usual for him to receive the ‘difference’, which in this case related to the respective capital values of the half-pay and full pay commissions. Naturally when the time came for him to return to active duty he himself was required to pay the ‘difference’. Alternatively, he could apply for a free vacancy created by augmentation after making a formal declaration that he had not received the ‘difference’ at the time of his earlier retirement.

William, Earl of Sutherland as colonel of the Sutherland Fencibles c.1760.

However, this only applied to regimental rank. Brevets were invariably gazetted as conferring rank ‘in the Army’ and were considered to be temporary. This meant that an officer promoted through one or more brevets had no right to sell them and only drew the additional pay of his brevet rank while he was actually serving. In the meantime he retained his regimental rank (and seniority) and eventually sold it or retired on to the half-pay accordingly. This could lead to decidedly unhappy situations and John Urquhart’s father, Lieutenant-General James Urquhart, was by no means alone in receiving only a captain’s half-pay of a bare five shillings per day.