The most comprehensive collections of British officers’ clothing, equipment and other possessions for this period are to be found in the National Army Museum, Royal Hospital Road, Chelsea, London; and in the Scottish War Museum (formerly the Scottish United Services Museum) in Edinburgh Castle. However, visits to individual regimental museums are also important as they frequently contain unusual items and relics not represented in the national collections.

At the Public Record Office, Kew, London, document class WO25 contains three sets of officers’ service records relating to this period. The first, compiled in 1809–10 covers lieutenant-colonels, colonels and general officers and typically lists promotion dates, stretching back to the 1760s or even earlier and, more importantly, also provide an often extremely detailed personal memoir of service. Two subsequent sets of returns compiled in the late 1820s cover all officers then on either full pay or half-pay. Although mainly covering the period of the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars, they also include family information lacking in the earlier 1809–10 series.

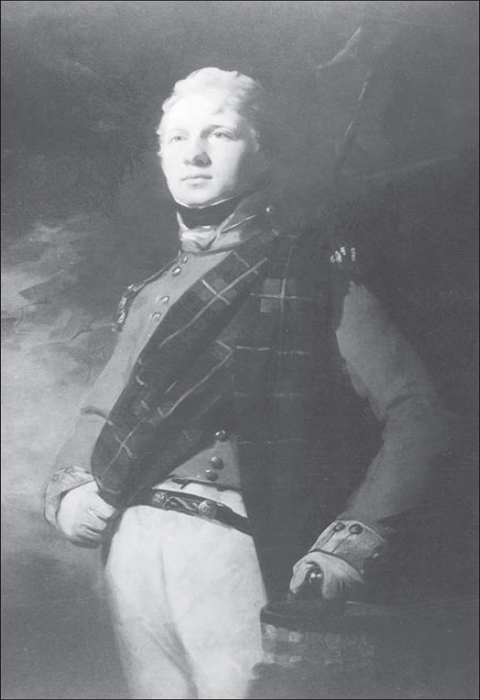

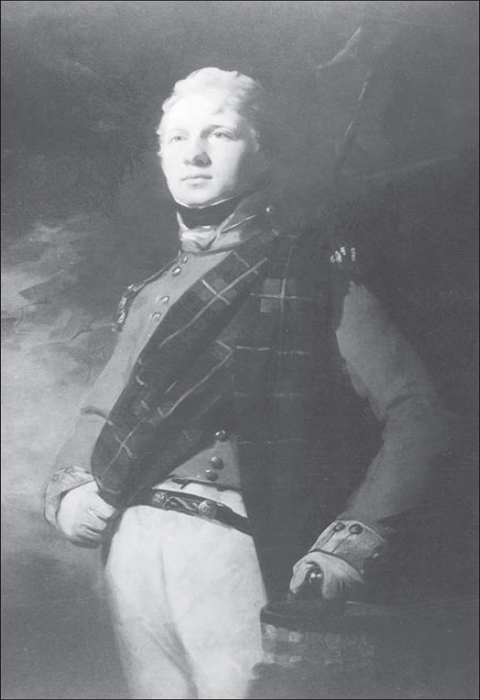

James MacDonnell: Third son of Duncan MacDonnell of Glengarry. Originally commissioned into 1st or Strathspey Fencibles 1793, Lieutenant 19th Foot 2 February 1796. Captain 5th Foot 10 September 1803. Major 2/78th Highlanders 1804 (as depicted here). Lieutenant-colonel (brevet) 7 September 1809. Captain and Lieutenant-colonel 2nd Footguards 8 August 1811. Served Maida, Peninsula and Waterloo. Wounded in defence of Hougoumont, where he and Sergeant Graham gained distinction by their closing the gate after the French got in. Colonel (brevet) 12 August 1819, Major-General 22 July 1830. Died 15 May 1859. (Private Collection)

Another important document class is WO31, containing the commander in chief’s memoranda papers from 1793 onwards. Most of the papers are (successful) letters of application for commissions, promotions and exchanges. The amount of information in the various letters and documents varies enormously, but the applications from individuals obtaining their first commissions contain invaluable information on their backgrounds; a typical example is quoted elsewhere in the study.

Naturally enough there are no re-enactment groups solely devoted to infantry officers, but there are a number of groups on both sides of the Atlantic recreating British infantry units throughout this period. Interpreting a Georgian officer is neither cheap nor easy. Ironically, it is probably still cheaper to buy an original 1796 pattern sword than one of the limited selection of reproductions, but otherwise proper clothing and equipment is extremely expensive. Where an officer interpreter is unable to afford the glorious magnificence of a full set of regimentals, however, it is essential that he obtains a good quality frock or undress uniform, rather than try to make do with a stage-quality costume made from inferior materials in tawdry imitation of a dress uniform. There is simply no substitute for employing the proper materials and – equally importantly – the services of a specialist tailor. However, producing a convincing interpretation of an officer does not rest on clothing and appearance. It is also necessary to construct a detailed legend, ideally based on information gleaned from WO25 and WO31, and then immerse himself in it in order to be able to behave like an 18th-century gentleman. Last and most important of all, an officer interpreter also needs to be as technically competent as his historical predecessors; just as required by the 1792 Regulations.