CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

ONE THING YOU WILL NOTICE EVENTUALLY, IF NOT IMMEDIATELY, is Harvard Square’s flatness—whereas Boston is a city of hills. There seems no inherently representative angle from which to take a definitive photograph, as the square actually isn’t square at all. Which speaks well for a place.

We lack the Italian’s idea of informal gatherings for the evening passeggiata: the lazy, leisurely perambulation that takes a while even to pronounce. Our own congregations tend to be either spur-of-the-moment or reserved for annual rituals like New Year’s Eve in Times Square or Fourth of July parades. Yet Harvard Square always has enough going on that people pause to hold up the cameras of their cell phones for a few shots that aren’t selfies.

The square itself is small-scale, and seen from overhead, Harvard Square resembles the diagram of a nerve reaching into finer fibers, much like the less traveled streets in and around an urban nucleus, and a lot of sky spreads above. Present-day etiquette means that people look straight ahead, avoiding eye contact. If Bill Cunningham passed through on his bicycle—to a New Yorker, Harvard Square would no doubt seem like a day in the country—he’d have an eye for this season’s Harvard Square style: To my eye, the dress is diverse yet so conventional that people appear to be in a kind of time warp, with their braids and Wayfarers, their backpacks, sandals worn with socks, summer dresses with thickly embroidered bodices, and baseball caps.

Knowing that a major Ivy League university is its backdrop, one can easily perceive Harvard Square in terms of what it isn’t: It’s the anti–Harvard Yard; no life of the mind is expected (assuming you jaywalk carefully); many of the people could be anyone, so you can’t be sure if you’re seeing a philosophy professor with pumped-up muscles or a visiting builder from Vermont.

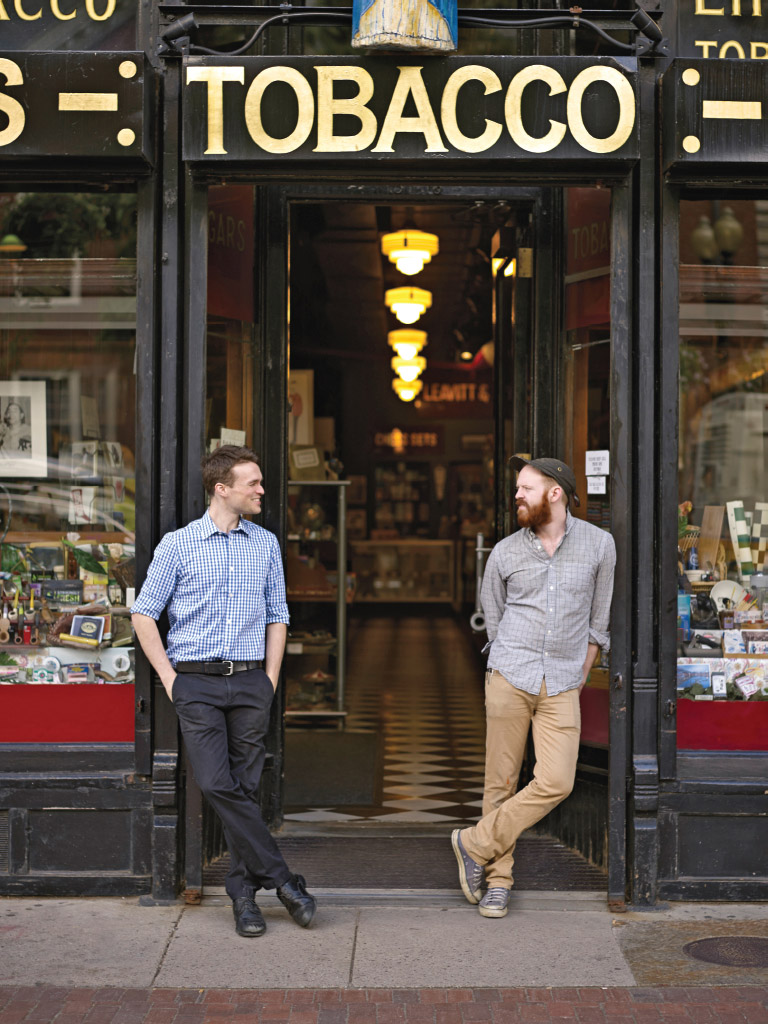

I went there on a recent July day, getting together with an old friend who’s nicknamed UB. He’s lived one square away from me in Cambridge since not long after we met in the late 1970s. Water bottles in hand, we walked and reminisced about what used to be where; he told me that the Garage, an indoor mall of restaurants and stores, really used to be a garage, and furthermore, his father used to park there. He said—with what I thought was respectful perplexity—that the square had a “quirky, almost indefinable idiosyncratic quality that persists despite the removal of so many of the old quirky, idiosyncratic establishments.” “Quirky” is the right word for the spirit of the place, partly because while every new generation has stamped it, certain things (not only people’s attire but their habits and desires, at least as reflected by commerce) do seem recognizable as a part of the yesterday that initially appeared radical, whose subsequent iterations have never quite erased the spirit of the original—or even tried to. The past permeates the present, though certain stores and restaurants—gathering places within gathering places—are gone. The mixture of old and new is slightly disorienting and sometimes dazzling, proclaiming the place’s timeless adaptability. The remembered images are like a sort of flip-book of your youth, letting you move through the succession of yous you have been.

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

Many people animate the square, as do squirrels, birds, and leashed dogs. The nearby parks get boring even for these creatures, apparently. But they aren’t the place itself, which remains just the same when they go away, with its cement sidewalks and low, unintimidating architecture; its nearby tunnel that sends buses and cars away from the congested center; its anonymous-looking subway entrances and exits; the nondescript “Pit” carved out like a small-scale arena with a few steps, intended for informal performances. Of course, Anywhere, U.S.A., has infiltrated: chain drugstores, Au Bon Pain, Starbucks. The beloved WordsWorth bookstore is gone, and Reading International as well. The amazing Grolier poetry bookstore (where the Cambridge police were sent in the 1950s when Allen Ginsburg appeared to read his banned poem, “Howl”) has survived, but is no longer a retail store. There’s no Brigham’s ice cream, though it has been replaced by stores with trendier flavors.

I lived at the edge of Cambridge for a mere year and a half, but I can still return and melt into the place. You can still be within Harvard Square’s microcosm and go to one of the big newsstands—Nini’s Corner or Out of Town News—to get news of the larger world and find out what’s happening in Alaska or buy a copy of French Vogue, and, across the street, choose between jars of capers or cornichons at Cardullo’s, just as Julia Child did when she was debating what to serve with the evening’s pâté.

IT’S ALWAYS INFORMATIVE TO THINK OF A PLACE NOT ONLY AS what it is but as what it isn’t. With the Big Dig surrounding Boston for so many years, the areas within its parameters became somehow smaller and reduced in scale, Harvard Square continuing to bloom as its own amaranth. It’s definitely not a place of faded glory. The square—usually not spoken of in precise terms but as a general area that encompasses everyone’s personal line of demarcation—is crowded though not chaotic. There are still enough alleyways and shortcuts to give the illusion that there’s something left to explore. We’re all familiar with the way we navigate familiar areas: We look for the landmarks at the same time we want to think the place is “ours,” that we have some information, or memory, or anecdote, or some unstated desire about a place—perhaps unstated even to ourselves—that makes it both public and personal, both real and exposed, yet still private. Either perception impinges on the other, but that’s another thing we’re familiar with: not having to reconcile our daily, tuned-out movement down a busy sidewalk, or through a park, or a square, with the same place that sometimes appears in our dreams; the place we can see as being entirely different when we return after dark. The dynamic changes; the light affects your mood and perceptions. There’s no simple description of place unless we tune out contradictions and ignore inherent mystery.

As a time capsule of America, we would unearth in Harvard Square the disparity of wealth; the omnipresence of vehicles; a vast number of earphones and iPhones; dirty puddles glistening on the ground, as well as tiny puddles of pureed chestnut and balsamic reduction squirted onto plates in one of its fancy restaurants. There’s no end to what this place listed on the National Register of Historic Places might show us about ourselves and our proclivities, our desire for the new—as long as the old doesn’t irrevocably disappear.

PUBLIC SPACES ARE ALL ABOUT WHAT CAN BE SEEN AND WHAT’S invisible. The person at the information kiosk can guide you to what’s apparent but can’t reveal the dynamics or the community’s assumptions about what the square should be. However cutting-edge some of the small stores might be or wish to be, the visitor is never overwhelmed by the architecture or intimidated by the clamor that often exists elsewhere in Boston. Drivers are almost mannerly. There’s a rustle of tree leaves, and a real romantic might be moved to think of Longfellow, and the “spreading chestnut tree” near the square, under which his village smithy worked.

Above us is that New England sky, so often confused and confusing: bright sun; sudden clouds; a drop in temperature that can rise even quicker than it fell. You take these changes for granted—or you do if you have a sweater or an umbrella and a bottle of water.

Rain or snow or sunshine, all subtly unite us, as does the presence of a person who has emerged from the T (the first-in-the-nation underground train, replacing the streetcars pulled down Massachusetts Avenue by horses since 1854), standing still in a square, passively requiring others to eddy around her. A great day! Blue skies! Harvard Square!

Then move along, because you’ll have to.

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL

CHRISTOPHER CHURCHILL