Photographs by ANDREW QUILTY

Oculi

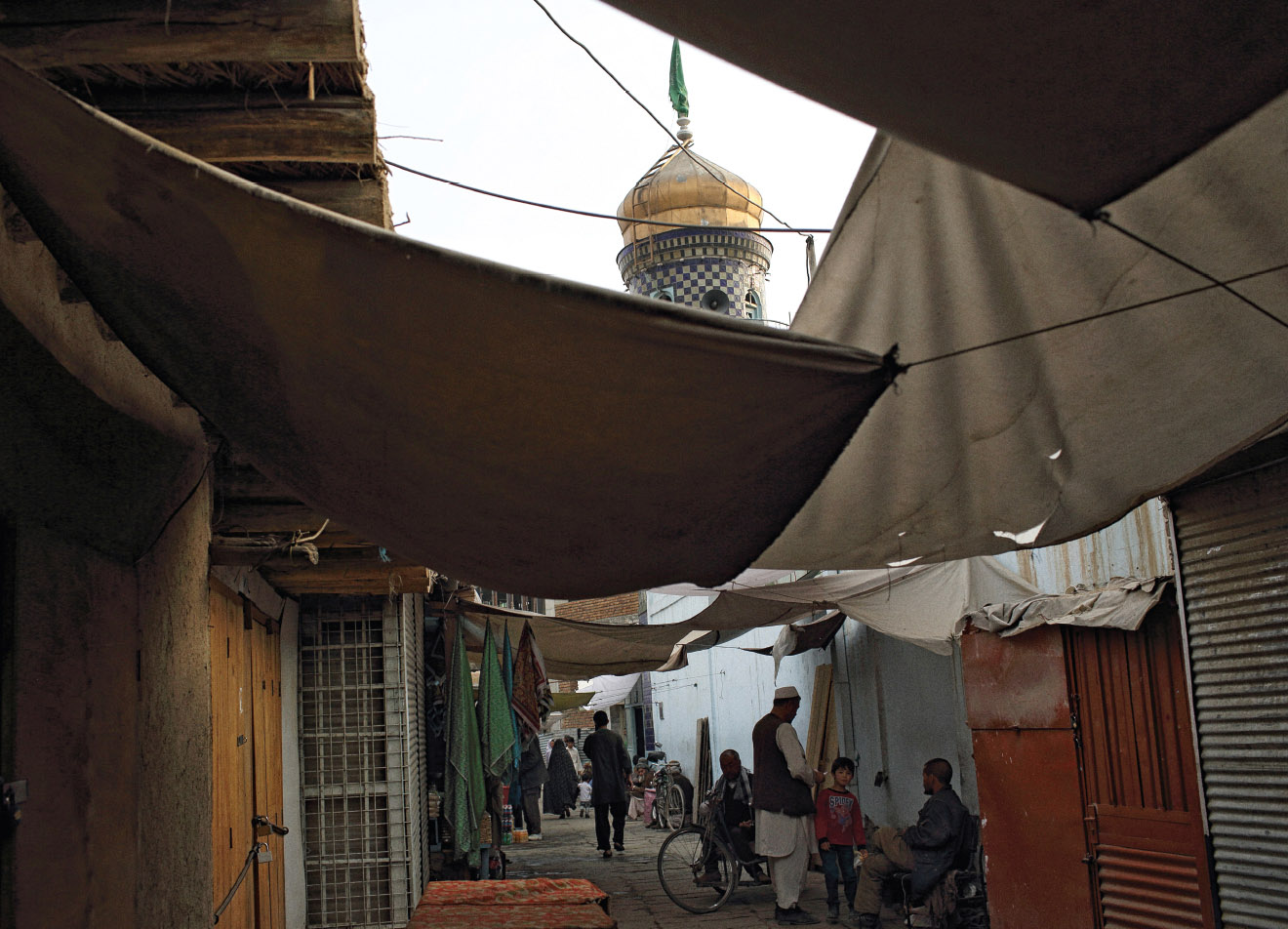

OLD KABUL WAS A CITY NOT OF SQUARES BUT OF NARROW LANES. For five thousand years, pack animals shuffled slaves, sugar, and silk between the Mediterranean, India, and China, through the funnel of the Kabul valley. The town blossomed into a winding maze of stables, warehouses, and workshops; wood carvers, jewelers, and calligraphers flourished in the alleys; the street level rose over the centuries; and new houses grew from fragments of wood, straw, and earth, first deposited at the time of Alexander the Great. In Bagram, north of the city, a spade uncovered a storeroom containing porphyry from Roman Egypt, lacquer from first-century China, and Indian ivories nailed to a crumbling two-thousand-year-old chair. But none of this industry resulted in a city square. In 1839 the British soldier James Rattray observed that “the streets are so narrow, that a string of laden camels takes hours to press through the dense, moving, ever-varying crowds who all day long fill the thoroughfares.”

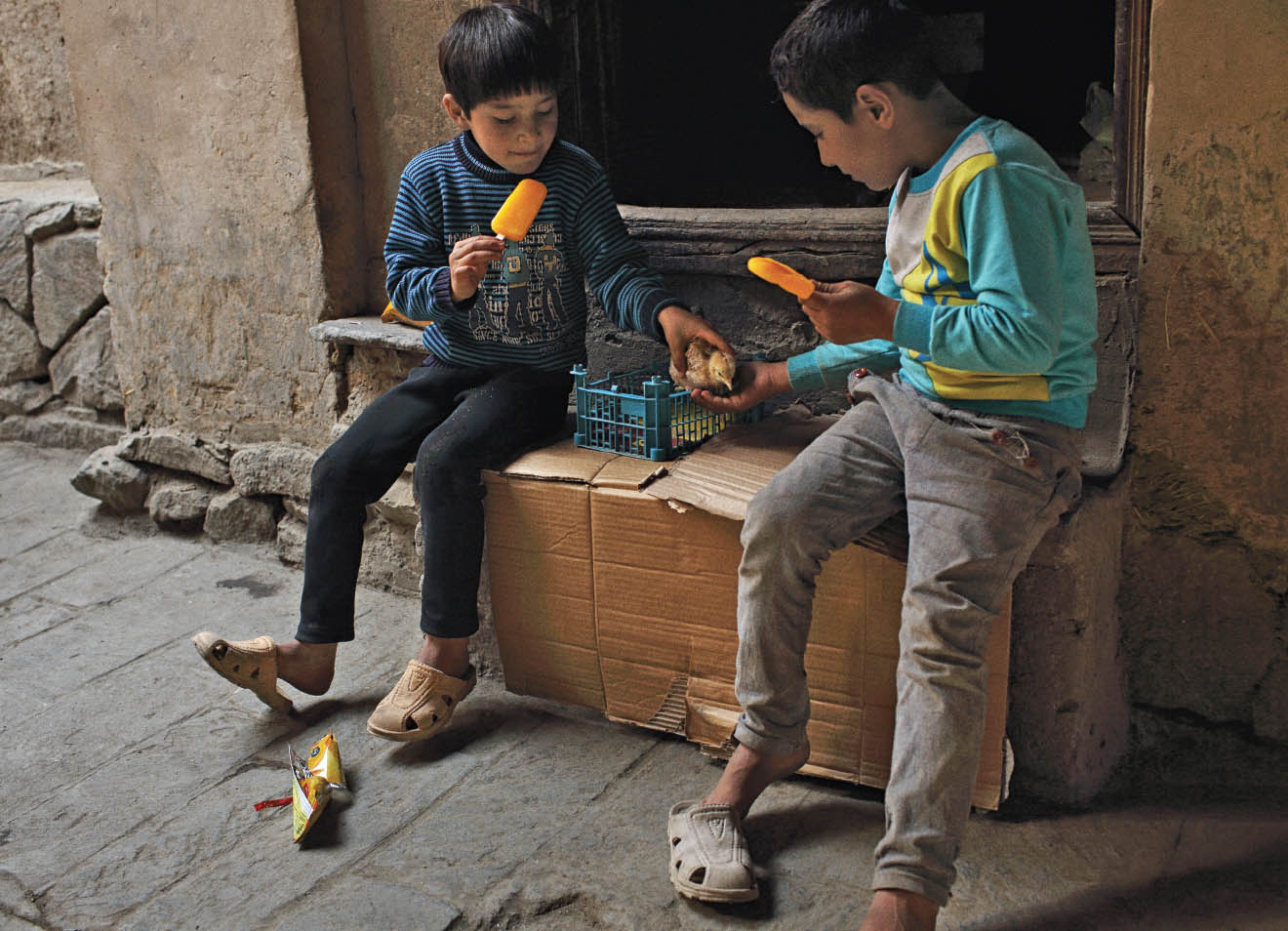

The narrow chaotic bazaar—the commercial space of workshops and stores—around the great mosques, beside the Kabul River, was kept entirely separate from the residential areas. If you had been permitted to penetrate the studded doors, tunnels, and winding passages that led from the bazaar to the residential lanes, you would have discovered generous courtyards, but these were private: inaccessible to all but the most intimate guests. Respectable families stayed behind the high walls of their compounds. They did not stand on the mud roofs like the men who pretend to fly homing pigeons, peering surreptiously into other men’s courtyards. And they certainly did not spend their days in the open like the “brave boys”—the jawanmard—sauntering in the bazaar or squatting in the open spaces to bet on wrestling, cockfighting, and dogfighting.

It was in 1639 that Ali Mardan, a Kurdish immigrant, first tried to give Kabul the equivalent of a square. He brought the idea from Persia, where his father, Ganj Ali Khan, forty years earlier, had demolished a square kilometer of shops and houses in the city center of Kirman (destroying the homes and livelihoods of thousands of Zoroastrian residents who tried—in vain—to protest to the Shah). In their place he had laid out a new formal bazaar, of fired bricks and glittering blue tiles, and a piazza three hundred feet long and a hundred and fifty feet wide. Ali Mardan followed this model, tearing into the informal sprawl of mud shops in the center of Kabul. He replaced them with four straight vaulted arcades—the Char-Chatta—arranged in a cross. It was the center of this cross of shopping streets that formed Kabul’s first real public space—not at the scale of his father’s in Kirman—but a formal secular square nonetheless.

Char-Chatta was famously beautiful, but we don’t know what exactly it looked like, because in December 1841 the Kabulis used this public space to display Sir William Macnaghten, the British resident in Kabul, after the uprising that drove the British from the city (his head, blue-tinted spectacles, and black silk top hat were placed on meat hooks, separately from his dismembered body). The British army demolished Ali Mardan’s bazaar in revenge. Squares are not natural phenomena, and in the absence of Ali Mardan, no one had the authority or confidence to impose a new architectural plan or stop a dense network of timber-framed shops from recolonizing the space. The Char-Chatta disappeared.

One hundred and thirty years later, in 1971, an East German foreigner chose to emulate Ali Mardan by building another square. This time he planned to place the square not in the commercial bazaar but in the residential neighborhood of Murad Khane. Delighted by the new plan, the government issued a forcible acquisition order for the whole area, paid some limited compensation, and began by demolishing two traditional courtyard houses in the heart of the district.

This demolition was supposed to be only the beginning. Under the master plan, all the other two hundred–odd historic houses of Murad Khane—almost the only part of the city to survive the British conflagration—would be bulldozed. The Qizilbash community, some of whom had lived for centuries in the ancient courtyards, would be resettled to concrete blocks on the city’s edge. A four-lane highway was to run through the intricate cedar columns of the caravanserai. Along the highway would stand concrete housing blocks, designed for 1970s socialist workers in an East German mold. In the center would be the new square.

But before the plan could be implemented, the president of Afghanistan was assassinated by Russian Spetsnaz storm troopers; the Soviet Union invaded; and redevelopment was put on hold. After the Soviet withdrawal, Murad Khane lay on the front line of the civil war. It was shelled from the city walls, residents were torn apart by rocket fire, and Ukbek militia bivouacked in the courtyards and burned the garden trees, wooden shutters, and panels for firewood. When the Taliban drove out the militia in 1995, the houses filled with refugees from outlying villages. During this whole period, no one built on the empty site, and no further houses were demolished. Forty years later, all that remained was the space where the two houses once stood, surrounded by the ancient residential streets of Murad Khane, a square in miniature.

When I first saw the Maidan-e-Pompa, the square of the pump, its surface was a composite of crumbling mud brick from old buildings, layered like a mille-feuille cake with bright blue and pink plastic bags and sprinkled with the feces of men and goats. Its new function as a garbage dump had raised the ground level in a slope, so that the north side was three feet higher than the south. Some of the studded wooden doors were so far below ground that residents had to climb over courtyard walls to enter their houses.

The entrance to the square was through the arch of a gate leading from the silver bazaar. Behind the gate were bridges built over the alley to prevent anyone from entering on horseback; they were now too low for pedestrians, so you moved up the lane bent double, as though in the entry to a mine shaft. Beyond the tunnels, high mud walls ran along either side of the lane. Set low into the walls were more thick studded gates, entrances to family houses. In the bazaar, just behind, someone once recorded a hundred thousand women in a week (on their way to pray at the shrine for children or for health, to lock a padlock or tie a thread around the railings), but now the lane was almost always silent and deserted.

A high mud-brick wall concealed on either side where one building ended and another began. The only windows were tiny squares twenty feet above the street level that could be used as firing positions. The Qizilbash of this area had been Shia in a Sunni city, Turkic-Persians among Pathans and Tajiks, and once wealthy courtiers when others were poor, and they had built this quarter to protect themselves from attack. Repeatedly in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the mobs had stormed the Qizilbash quarters, and the Qizilbash had tried to protect their families, firing position by firing position, tunnel by tunnel, studded gate by studded gate. The lane also protected the inhabitants from the other lanes. Each originally protected a separate clan. Access from one lane to another could be had only from the main bazaar street and the guarded gate.

But when the courtyard houses were demolished and the square was created, everything changed. Two very separate lanes were suddenly connected. Or rather, they ceased to exist: when you emerged from the narrow tunnels, there were now no lanes. Instead of facing the blank mud wall of an unbroken terrace, you could stand in the center of the old terraces and see the facades of houses designed to be invisible. The private had suddenly become public.

You could see, how, on every inner courtyard, from roof crest to ground, the houses were faced with carved sliding panels; each panel could be raised in the summer to create an open colonnade; the panels were decorated with flowers; and they were separated by thick cedar columns carved with lotus flowers and acanthus leaves. You could see peacocks carved on every window frame. The opening of the new square had granted these houses identities and facades.

Thus, the Maidan-e-Pompa—this accidental, embryonic space—allowed me to glimpse for the first time the hidden courtyards of the old city of Kabul. Through seeing them, I fell in love with them. I decided to move to Kabul, to get closer to these buildings, to restore them, and to support the lives and crafts of the residents. I began in the square itself, asking whether the residents would allow me to clear the garbage. There was suspicion. Some believed I was searching for buried treasure left by the British in 1841. But eventually, Kaka Khalil, the chief of the lane by the shrine, agreed to work with me, and so did the champion wrestler three lanes farther down.

We established a small charity—Turquoise Mountain. With a hundred other local residents, we began by clearing the garbage out of the square, dropping the street level by three feet: allowing for the first time, in half a century, people to walk upright beneath the bridges that led into the lanes. People could now enter their houses through the door, instead of climbing over the compound wall. We stripped the mud off the house at the north end of the square till it stood in bare timbers; we jacked it into the air, replaced its waterlogged, wooden foundations, cleaned half an inch of black caramel off the plaster niches—when the princess’s family left, it had been used for boiling sugar—and repaired each peacock in the window frames. (We eventually repaired over a hundred such residential houses.) We paved the edge of the square and planted grass in the center and lined it with plane trees, and on the south side we placed a water pump—which was why this wasteland without a name became known as the Maidan-e-Pompa. Children from families on both sides of the square began to congregate at the water pump. The boys used it as a soccer field.

ANDREW QUILTY/Oculi

But I never could have predicted how the community would take to the new square. When we opened a primary school on the south side of the square, the two hundred children who turned up on the first day were almost all boys. The fathers said they did not trust what we might teach their daughters. So we invited the fathers to sit in the back of the class (after two weeks they were so bored that they were willing to allow their daughters to attend). When the community asked for a clinic, I resisted because I was worried about insurance, and because a clinic was “not in my strategic plan.” But the residents insisted, and offered another room adjoining the square, and I reluctantly agreed. The wealthier residents agreed to pay more for their treatment, in order to subsidize the poorer residents, and the clinic became the most successful part of the square.

After five years of clearing garbage, leveling streets, installing water supply and electricity, and restoring buildings, we had created, around the square, an architectural office, a community center, a tea shop, a woodworking shop, a masonry yard, the beginnings of a school of traditional crafts, a primary school, and a clinic. But most of this was invisible, still hidden behind the high mud walls of courtyard buildings that formed the edge of the square. The schoolchildren trooped in their pale blue uniforms from the bazaar, past the old wooden gate, under the tunnel, then, at the corner of the square, turned through another studded gate and up an old staircase out of sight. You could hear the sound of their chanting lessons through the narrow window, twenty feet in the air, but that was the only hint of a school.

And then the square fought back. One of my foreign volunteers thought, for example, that a playground would be a good idea, since there were none in the area. But the community would not accept a playground in the square. Instead they offered us an empty compound, just behind the lane gate, on the back of the bazaar. We got the children to design their own slides and swings and tunnels. And for a year they seemed to use it happily. But one day I returned from a trip out of the country and found the playground locked. After three days I managed to enter and found a goat in the playpen and chickens on the broken seesaw. No one could quite give me a straight answer on what had happened. A couple of months later, someone asked if we could relocate the architectural office. Finally, people offered a good alternative site for the primary schools and clinics, just three hundred yards away but no longer in the square. The square was folding back into the private space of the residential lanes, and all the other activities were being pressed beyond the studded gates into the bazaar.

Our long-planned institute for training craftspeople emerged, not on the square but in what once was a merchant’s warehouse and mansion on the riverfront. When it was offered to us, goats lived in the upper stories, banana boxes were shoved against the crumbling plasterwork, and lightbulb crates filled the courtyard. We had to restore more than a hundred separate rooms. We created a library in a high narrow courtyard with white-plastered walls; we placed the finance department in a tiny gallery of first-story wooden balconies; and we put a calligraphy school in a vast courtyard faced with forty-eight separate carved panels, on four sides, with tall cherry trees and an explosion of flowering vines. Sixty jewelers and gem cutters trained in rooms set with tiny shards of red and blue glass pressed into the plaster two hundred years earlier. The rear buildings were taken over by wood carvers and filled with the sweet scent of sawed cedar.

Next the community offered us a caravanserai on the river’s edge—originally used to house the horses and goods of traveling merchants—as a site for a ceramics school. We moved the primary school out of the square into another courtyard house beside the bazaar, and we rebuilt a large area of warehousing into the clinic, now treating twenty-three thousand patients a year. In front of this complex of buildings sat the champion wrestler in his plastic chair, squeezing his arthritic knee and telling stories about hoodlums from his youth to calligraphers and fruit sellers. The blacksmiths—standing in special pits so they could keep the anvil on the ground—smiled as they beat molten metal. Students, patients, jewelers, and shopkeepers moved daily through the line of rubber-bucket sellers and brewers of magical potions. We had saved many traditional buildings and were selling crafts, which had seemed doomed to disappear, on three continents. The project of regenerating Murad Khane had never appeared so successful. But all our sites had been gradually shifted into the much older context of narrow streets, trading courtyards, and bazaar alleys beside the river. It was no longer in the new space of the square.

I tried to convince myself that our institutions were inspired by that square, even if they had reemerged away from it. I felt that the open space where the wrestler sat was a kind of square: It was a space that brought together men and women, the Qizilbash and others (although in truth, it was simply the place where the bazaar street came out on the riverbank; it looked nothing like a square). I often walked back from our institute, through the bazaar and past the wooden gate, toward the old square. The sounds of children chanting their lessons or the masons knapping flint had gone, but children from both sides still gathered around the water pump. On those visits, the square seemed to me, a European, the quintessence of the ancient city. But I was beginning to realize that what I so loved about that square (and any square)—the glimpses of the private facades, the intersection of the two quite different streets, and the open public space in between—was, for many of the Qizilbash, a scandal.

I realized that, in a decade, I had never seen an adult sit or even stand under the plane trees that we had so carefully planted in the Maidan-e-Pompa. If the trees were there at all, it was because I, not the community, watered them and, more often than I liked, replanted them. The center of the square had reverted to a dirt patch. Kaka Khalil did not greet the people on the other side of the square, because they lived in what was, in his father’s day, the separate lane of the Afshar. No one seemed to ever take the shortcut through the middle of the square. Instead, if people were walking from the bazaar, they stayed to the barely visible line of the old streets. Over forty years had passed since those two courtyard buildings had filled the entire space, creating a solid wall between the two streets. But everyone except the youngest behaved as though they were still there. The community backed our projects, the craft schools and clinic were flourishing, but they were determined that they should stay in the bazaar and never return to the square. The old fortified private lanes seemed to persist in the imagination, although their gates could no longer be closed.

Murad Khane had survived the East German plan and the Afghan government demolition order; it had survived my attempt to bring workshop, school, clinic, tea shop into the square or to make it a place for adults to relax or children to play. And I suspect that it will not be a decade before the space has been colonized again with private houses and the old locked alleys have reappeared. And old Kabul has again lost its square.

ANDREW QUILTY/Oculi

ANDREW QUILTY/Oculi