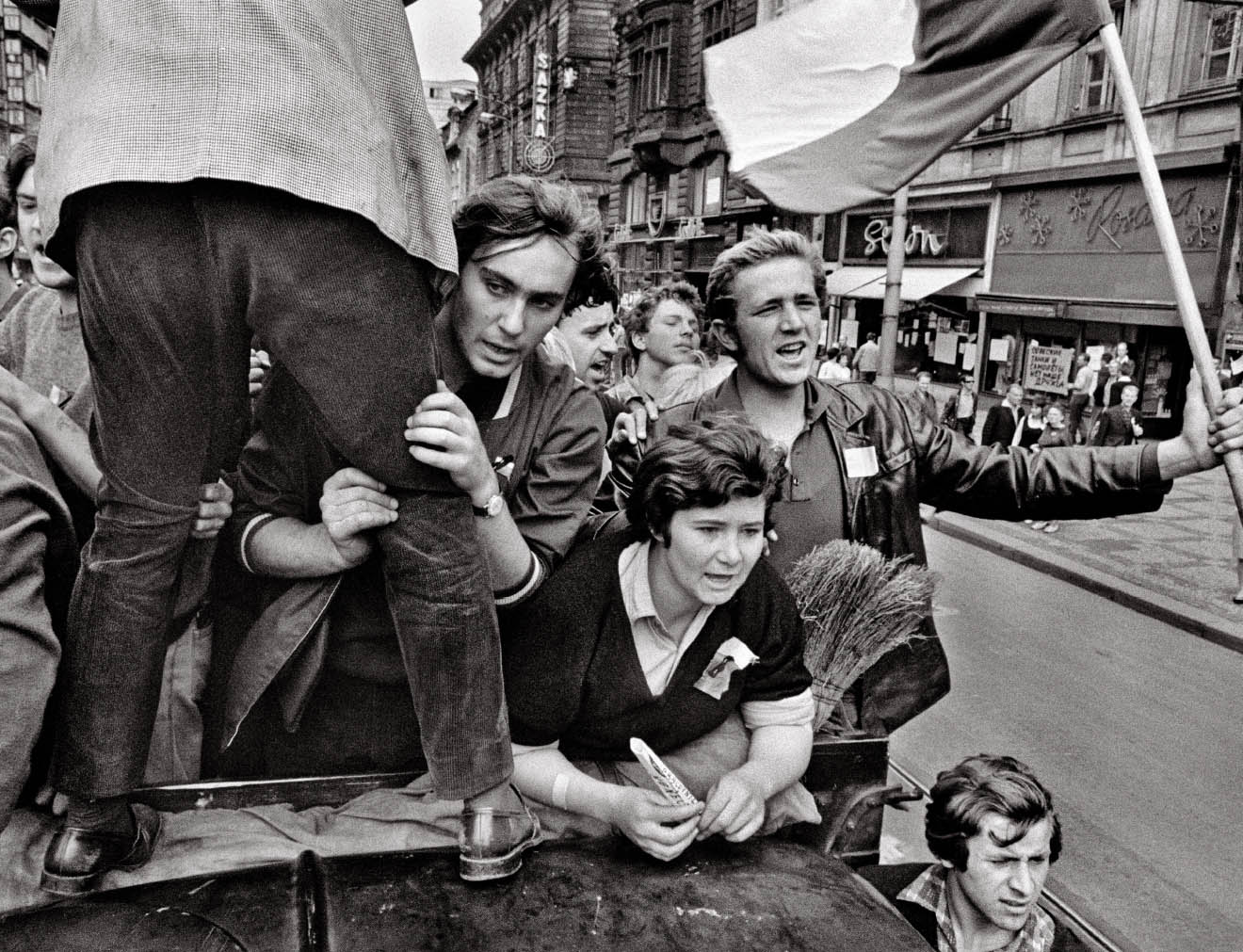

JOSEF KOUDELKA

Magnum Photos, Wenceslas Square, Prague, August 1968

WHENEVER I VISIT A GREAT FOREIGN CITY, I AM DRAWN TO ITS public squares, the scenes of ancient horse trading and market gossip, military coups and populist uprising. Even in Moscow, where I lived for years and still visit frequently, I cannot resist the pull of Red Square, the ultimate agora. Over time Red Square has been the scene of Orthodox worship; vigorous commerce in livestock, food, housewares, and books; public executions; the declarations of the tsar; political agitation; military displays; and mass protest rallies. The tourists who come from the Russian Far East, from the Caucasus, from the Polar North, can sense on Red Square a ghostly parade of Soviet history, bloody and tumultuous, drifting across the cobblestones.

Sometimes there are startling, and amusing, changes. In the 1990s, after the fall of the Soviet Union, GUM—the enormous department store and arcade that was commissioned by Catherine the Great and that faces onto the square—was suddenly filling with Western luxury brands so expensive that wry Muscovites referred to it as “an exhibition of prices.” In 2013 even the most ironical and cosmopolitan post-Soviet citizen was taken aback to arrive at the square only to find there a Louis Vuitton trunk two stories high. The square had been a kind of sacred place: For people of a certain age, it was the scene of high Sovietism, not commercialism. The gigantism of Louis Vuitton’s luggage museum seemed a Western capitalist step too far. After absorbing countless messages of protest, a spokesman for Vuitton said the company had agreed to remove the trunk “so as not to upset any sensibilities.”

The Kremlin and Red Square outside its walls was designed to be the center of a great political and spiritual power. Ivan the Terrible, then agents of subsequent tsars, read their decrees from Lobnoye Mesto, the Place of Skulls, a stone platform not far from St. Basil’s Cathedral. On Palm Sunday, the patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church would ride a donkey on the square as a reenactment of Calvary. A praetorian guard known as the Streltsy used to guard the Kremlin and were considered a cherished military elite—until 1698, when they staged an uprising against Peter the Great. The executions were grotesque: hangings, the roasting of flesh, the ripping apart of men with iron hooks.

After the Bolshevik Revolution, Lenin returned the capital to Moscow from Petrograd. Red Square resumed its centrality. Lenin began the Soviet tradition of military display and Communist exultation. But to get a sense of the sacral centrality of Red Square, dig up (on YouTube) the twenty-minute color film of the Victory Day celebration on June 24, 1945. It is a gray, drizzly summer morning. The clock on the Kremlin bell tower strikes ten; representatives from every division in the Red Army and Navy have assembled on the square. And standing on Lenin’s Tomb—the salmon-colored polished granite structure known to the military and secret police as Post Number One—is Stalin. A great parade of men and hardware begins. In the thirties, Stalin ordered that the cobblestones of Red Square be made thick enough to absorb modern weaponry, and now row after row of tanks, machinery that helped crush the German army, grinds across the vast plaza. Then comes the most dramatic moment of all: Soldiers from various divisions bring various Nazi military flags and standards toward the tomb and throw them into a heap. This was the apotheosis of Red Square as the scene of Soviet triumph.

Victory parade, Red Square, Moscow, June 24, 1945, courtesy RussianArchives.com

THE SOVIET LEADERSHIP EMPLOYED RED SQUARE AS AN ARENA of awe. The few who dared to challenge the Soviet leadership saw it as an arena of confrontation. This is the case for many capital squares on earth—the square is the arena of political confrontation.

In August 1968 Soviet and Eastern bloc tanks rolled into Prague, crushing the Prague Spring, Alexander Dubček’s Action Programme of political liberalization, which had brought far greater civic liberty to Czechoslovakia. Soviet troops and intelligence agents arrested and brought the Czech leadership to Moscow; the cars rumbled across Red Square and through the Kremlin gates. A new period of “normalization”—meaning full-blown state repression—returned (and would stay in place for the next nineteen years). The Soviet press instructed the population on the ideological waywardness of Dubček, accusing him of regressing to capitalism, just as it had done during similar uprisings in Berlin and Budapest.

At that time, there was no “dissident movement” in the Soviet Union, but there were tiny pockets of people, mainly in Moscow and Leningrad, who met in kitchens to talk about politics, culture, and the world beyond the Soviet Union. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who had been able to publish during the post-Stalin “thaw,” was working secretly on The Gulag Archipelago. In June 1968 the physicist Andrei Sakharov wrote what would become his most famous essay, “Peace, Co-existence, and Intellectual Freedom.” And Natalya Gorbanevskaya, a poet well known among Moscow and Leningrad intellectuals, went about conceiving something audacious.

On August 25, 1968, Gorbanevskaya (with her three-month-old son in tow) arrived at Lobnoye Mesto, on Red Square, at noon with seven others, including Viktor Fainberg, a philologist who had spent a year in prison in the 1950s because he fought back against an anti-Semitic attack; Larisa Bogoraz, a linguist who was married at the time to the jailed dissident writer Yuli Daniel; and Pavel Litvinov, the grandson of Maxim Litvinov, who had been Stalin’s first People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs. Very calmly, the group sat down on the stone platform where Ivan the Terrible once spoke, and they unfurled a series of signs: “Hands off Czechoslovakia!” “Shame on the Occupiers!” “For Your Freedom and Ours.”

After just a couple of minutes, agents of the KGB arrived on the scene.

One officer belted Fainberg mightily, knocking out his front teeth. A van pulled up to the scene, and the officers hauled the protesters away. Some were sentenced to labor camps, some to internal exile. Presumably because Gorbanevskaya had an infant, the authorities waited a year before arresting and punishing her. In April 1970 she was (falsely, absurdly) declared a “chronic schizophrenic” and thrown into psychiatric prison, first in Moscow, then in Kazan, and given a debilitating course of drug “treatments.” She was released after two years. (In 1975 she emigrated to Paris.) But something had been achieved. As Gorbanevskaya told the dissident journal The Chronicle of Current Events, “We were able for a moment to break the flow of unbridled lies and cowardly silence and to show that not all citizens of our country agree with the violence that is happening in the name of the Soviet people.”

In private, the Soviet authorities very coolly assessed the Red Square event—all five minutes of it—and sensed that there was behind it a growing sense of opposition to their leadership and to the regime. Yuri Andropov, then the head of the KGB, went before the Party’s Central Committee to report on this relatively amorphous-seeming phenomenon of dissidence: “They do not have a definite program or charter, as in a formally organized political opposition, but they are all of the common opinion that our society is not developing normally.”

The men and women who came to Red Square to protest against the invasion of Czechoslovakia went barely noticed by the vast majority of the population, and yet they provided inspiration to Czech democrats, including Vaclav Havel, who heard about them through underground channels. “For the citizens of Czechoslovakia,” Havel said, the demonstrators who came to Red Square out of a civic sense of duty represented “the conscience of the Soviet Union.”

Mikhail Gorbachev, the future (and last) leader of the Soviet Union, was a young man in 1968, but he had Czech friends who had believed in Dubček and Russian friends who very privately expressed dismay at the regime even as they climbed the Party ladder. In 1987 Gorbachev was asked the difference between Prague Spring and perestroika. “Nineteen years,” he said.

IT HAS BECOME COMMONPLACE TO ASK WHY DICTATORS AROUND the world simply don’t replace their city squares with skyscrapers, or barbed wire, or garbage dumps—anything to dissuade the restive masses from assembling and voicing their demands. Does Hosni Mubarak regret not having run a highway through Tahrir Square? How long before Recep Tayyip Erdogan builds the Taksim Mall in Istanbul? Even in a democracy, you wonder if leaders don’t sometimes regret their own city squares. Isn’t it possible that, during the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations, the mayor might have wished he’d built an arts center in Zuccotti Park?

The central square, once the locus of power, of military display and political parades, is a constant point of anxiety. Tiananmen Square in Beijing. Independence Square in Kiev. Freedom Square in Tbilisi. Ala-Too Square in Bishkek. Azadi Square in Tehran. Dignity Square in Daara, Syria. Pearl Square in Manama, Bahrain. In every one of these places, and in many more, there have been major upheavals, set pieces of political drama.

In 1989 my wife, Esther Fein, and I were working in Moscow as newspaper reporters, she for The New York Times and I for The Washington Post. (We had done plenty of reporting from Red Square; Revolution Square, in Leningrad; and various central squares around the Soviet Union, particularly in the Baltic capitals: Tallinn, Riga, and Vilnius.) We arranged to meet some friends in Prague for Thanksgiving; they were coming from Germany, where they had just covered the epochal breach in the Berlin Wall and the onset of revolutions everywhere.

The night before we arrived, there had been a demonstration on Wenceslas Square, largely students. Riot police had cleared the square, and the rumor was that someone had been killed in the melee. Wenceslas Square had been the scene of tragedy before. In January 1969 two students, Jan Palach and Jan Zajíc, burned themselves to death to protest the Soviet repression of the Prague Spring. Now the square was filled with students handing out leaflets, arranging demonstrations and teach-ins. Day after day there were demonstrations on the square, and the Czech Communists, lacking any commitment of support from Moscow, and seeing what had already taken place in Germany and Poland, began issuing concessions.

But it was too late. Soon Havel, accompanied by the once-fallen leader, Alexander Dubček, spoke from a high window above the square and vowed to bring freedom to Czechoslovakia. Down below, the people shook their keys and shouted, “Havel to the Castle!” as if this were the musical-comedy version of Kafka. A dissident playwright, a former political prisoner . . . to the Castle! And, of course, that is precisely where he went, via democratic election.

In my experience, the drama on Wenceslas Square was one of the very few set pieces that led, more or less, where one might have wished. A kind of historical enchantment. Havel went from being a dissident to running the nation, and as president, he never lost his sense of moral direction, his modesty, his sense of the absurd. Yes, the set piece on Wenceslas Square ended well and stayed—at least for now—on a desirable path.

“What happened in November 1989 is well known,” wrote Ivan Klíma, a novelist who was a prominent player in both the Prague Spring and the events twenty years later. “Not a window was broken, not a car damaged. Many of the tens of thousands of pamphlets that flooded Prague and other cities and towns urged people to peaceful, tolerant action; not one called for violence. For those who still believe in the power of culture, the power of words, of good and of love, and their dominance over violence, who believe that neither the poet nor Archimedes, in their struggle against the man in uniform, are beaten before they begin, the Prague revolution must have been an inspiration.”

JOSEF KOUDELKA

Magnum Photos, Wenceslas Square, Prague, August 1968

NO REVOLUTION HAS A SINGLE SOURCE. THE REVOLUTION I WAS witnessing in the late 1980s and early ’90s, in Moscow and beyond—the implosion of communism and the Soviet Union—had many sources: the widespread cynicism about ideology; the collapse of the economic system; cheap oil; the rise of a technological age; dissent of various forms around the empire; the independence movements in the Baltic states and, later, Ukraine and the Caucasus; pressure from the West, including Reagan and every other president since the end of World War II; the moral suasion of the human rights campaigners; the demands of a new generation; and above all, the well-intentioned but ultimately futile attempts by the reformist wing of the Party, led by Mikhail Gorbachev, to rescue the situation.

And to see this drama play out, one could do worse than witness the set-piece dramas on Red Square. When I arrived in Moscow in 1988, May Day was in its final throes of Sovietism. On my first trip to the celebration, I saw all sorts of Party-approved reformist slogans: “Uskorenie!” (Acceleration!) “Perestroika!” (Rebuilding!) The parade was more a late-Soviet version of halftime at a bowl game than a Stalinist propaganda fest. The Party had stripped away, as much as it could afford, any sign of Cold War confrontation. There was no sense of threat or swagger.

The following year, 1989, with uprisings on the horizon throughout Eastern and Central Europe, the slogans grew even more benign and cloying: “Peace for Everyone!” “We’re Trying to Renew Ourselves!” It was almost as if one would eventually find a sign, in the name of the Party, reading, “Please! Don’t Be Angry with Us! We’re Trying! We Really Are!” Or “Have You Noticed That We’re Letting Eastern Europe Go Its Own Way?”

By May Day 1990, Red Square was ripe for upset. It was Tocqueville’s insight, while writing about the French Revolution, that the most vulnerable and dangerous moment for any regime is the moment when it liberalizes. In many of the Soviet republics and in some Russian cities, May Day had been canceled. The central authorities decided to go ahead, but with concessions. In the weeks before the event, the head of the Moscow Communist Party organization announced that factory workers could march or take the day off, their choice. Very relaxed. The Party leadership also allowed various opposition organizations, including Democratic Platform and Memorial, to join in the festivities so long as they did not carry any seditious banners.

My colleagues assembled on the reviewing stand. It was, by Moscow standards, a fine spring day. There was minimal traditional agitprop. One of the first sounds to come blaring out of the loudspeakers was Pete Seeger crooning “we’ll see that day come round,” from “One Man’s Hands.” The members of the Party politburo, in addition to well-known liberals like Gavriil Popov, the economist-turned-Moscow-mayor, took their places atop Lenin’s Mausoleum to review the parade. (Boris Yeltsin told me how Gorbachev handed out the assignments on where everyone should stand; at the luncheon afterward, people sat at the table according to their rank.)

The first hour was uneventful, benign, like the previous year. Gorbachev alternated between a pleasant smile and a studious boredom; he had been to so many of these parades before. In fact, some of the early signs carried by factory workers—“Enough Experiments,” “A Market Economy Is Just Power to the Plutocracy”—seemed to indicate a conservative anxiety about the future of economic reform. (A well-founded anxiety, as it turned out. The post-Communist plutocracy and the way they lived would make the privileges accorded to the Party elite look trivial by comparison.)

But somehow the tenor of the parade, and the marchers themselves, changed suddenly, unaccountably, the way the temperature of the ocean can change suddenly as you swim from one depth to the next. Now there were flags from Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia—a clear and impudent display of support for the independence of the Baltic states. Then we saw the old red, white, and blue Russian tricolor. Was this the first time anyone had seen such a flag on the square since Nicholas II?

Now came the more daring banners: “Socialism? No Thanks.” “Marxism-Leninism Is on the Rubbish Heap of History!” “Seventy-two Years on the Road to Nowhere.” “Ceauşescus of the Politburo: Out of Your Armchairs and into Prison!” There were portraits and tributes to Boris Yeltsin and Andrei Sakharov. And perhaps most terrifying of all to the members of the Party leadership, red Soviet flags with the yellow hammer and sickle cut out—an echo of what had been seen in places like Bucharest, where the Party leadership met a bloody end. Gorbachev never betrayed any emotion, no outrage or even surprise. He did not flinch even when a Russian Orthodox priest stood in front of the mausoleum, hoisted a huge crucifix and bellowed, “Mikhail Sergeyevich, Christ has risen!”

Yegor Ligachev, Gorbachev’s conservative rival in the ruling politburo, writes in his memoirs that the alternative groups on Red Square were “crazies.”

After about twenty minutes of this, when the anti-Kremlin slogans could no longer be ignored or absorbed by the politburo as the harmless outpouring of democratic faith, Gorbachev turned to Ligachev and said, “Yegor, I see it’s time to put an end to this. Let’s go.”

“Yes, it’s time.”

Later, after they had descended from the mausoleum and left Red Square, Ligachev, in front of other politburo members, scolded Gorbachev, telling him that such events were “confusing the country.” Ligachev did not get a positive reply. Gorbachev, he writes, “waved off my warning and reproached me for harping on the same old thing.”

There would not be a May Day demonstration on Red Square for over a decade. There were, however, other sorts of demonstrations. In 1991 fourteen members of a performance group calling itself ETI, or Expropriation of the Territory of Art, lay down on the cobblestones in front of Lenin’s tomb and spelled out the word “khui” (cock). These artist-provocateurs were, as the Russian slang goes, “giving the cock” to Soviet power. Which is immensely more obscene to the Russian ear than a raised middle finger.

REVOLUTIONS DO NOT END WITH THE RALLY AT THE SQUARE. IT is not even clear that revolutions end.

One of the most remarkable things about Jehane Noujaim’s documentary The Square is the way that it refuses to hand itself over to romanticism—the legitimately thrilling outpouring of liberating emotion and the momentary sense of triumph—that surrounded the events of 2011. By staying on the scene month after month, year after year, Noujaim and her team portray not only the heroism of the demonstrations but also their complexity, their contradictions, and the forces arrayed against the goals of pluralism and democratic practice. History is not played out solely on the square. The institutions of power are too often impregnable. And even if the focus of protest falls—Hosni Mubarak, in this case—that is hardly proof that the institutions he represents will shrivel and disappear.

The early huge demonstrations on Tahrir Square were both shocking and exhilarating. They were demonstrations of will. But Wenceslas Square, and then the long and transformative presidency of Vaclav Havel, is the rarity, the exception. The Czech historical experience was such that it had relatively recent historical memory of democratic practice and a market economy. They suffered terribly for a half century under Soviet rule, but that history was a kind of resource—a political, economic, and spiritual resource lacking in so many other places. Similar set-piece dramas on squares in Beijing, Tripoli, Bishkek, Manama, Yangon, and so many other capitals have met with resistance, blood, counterrevolution, and deepened repression, not least to make sure that no movement comes to the square again.

Sometimes a regime even moves the square. In 2005 the military junta in Burma moved the capital to the inland city of Naypyidaw. Sometimes a regime makes sure that its public space is reserved solely for the display of its own power: In Riyadh, Deera Square is known (to those who dare) as “Chop Chop Square” because it is used, most notoriously, for the executions of murderers and adulterers, to say nothing of people deemed to be practicing witchcraft.

But just because demonstrations on the square—in public space—do not lead, in most instances, to the swift democratic election of a wise and gentle philosopher king (or queen), the sheer act of congregation surely has lasting effect. Egypt today is back in the hands of an authoritarian regime, led by General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, that is, arguably, worse than that of Mubarak. But Egyptians are not likely to forget Tahrir and their brief period of empowerment. As has been said, democracy is not a one-day event, a sudden uprising of popular will commemorated with subsequent annual parades; democracy is a process, an evolution.

THE DREAMY NARRATIVE OF WENCESLAS SQUARE DID NOT COME to Red Square, nor to Tiananmen or Tahrir or so many others. And to anyone who watched the May Day outpouring in 1990, or the resistance to the August 1991 coup, Putin’s Russia must feel like a profound disappointment. Russian history, which spans a thousand years of autocracy and totalitarianism, could not be overcome quite so easily. The pursuit of both democratic politics and a free market in the 1990s was so chaotic, so untethered from a legal structure, so riddled by greed and corruption, that Russians came to scoff at the word demokratia and use the derisive dermokratiya (“shit-ocracy”). Putinism is the nationalist-authoritarian reaction to those years.

But even while the regime is said to be enormously popular (thanks in large part to the state’s grip on television and, increasingly, the Internet), the urge toward the public square does not fade. In January 2012, as an anti-Kremlin, anti-corruption movement was brewing in Moscow, eight members of the radical-feminist anti-Putin collective known as Pussy Riot, wearing identity-concealing balaclavas, climbed Lobnoye Mesto, chanted, “Putin is scared shitless,” and began singing their song “Raze the Pavement!” Before the authorities could drag them from the stone podium and arrest them, they sang:

Free, free, free the pavement!

Egyptian air is good for the lungs,

Turn Red Square into Tahrir!

Have a great day among strong women,

Tahrir, Tahrir, Tahrir, Tripoli!

After pulling off another protest action, this time in the city’s largest cathedral, the seat of the Russian Orthodox Church, two members of Pussy Riot—Nadia Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina—were arrested, endured a modern show trial, and were sentenced to a prison camp. Before they were sent to jail, Tolokonnikova delivered a closing statement that echoed the spirit of the men and women who first went onto the square forty-four years before, in August 1968.

“I don’t consider that we’ve been defeated. Just as the dissidents weren’t defeated. When they disappeared into psychiatric hospitals and prisons, they passed judgment on the country,” she said. “Don’t twist and distort everything we say. Let us enter into dialogue and contact with the country, which is ours, too, not just Putin’s and the patriarch’s. Like Solzhenitsyn, I believe that in the end, words will shatter concrete.”

The members of Pussy Riot were young, and they had the daring of youth. They took their acts of protests to the very center of Russian power: Red Square and the altar of the most famous Orthodox cathedral in the country. As Tatiana Volkova, an art curator and activist, writes, “The center of power is inaccessible.” Until Pussy Riot dared to ascend Lobnoye Mesto, the protests had been held across the Moscow River on another square, Bolotnaya Square (or Swampy Square). Any attempts to cross the Great Stone Bridge and march toward Red Square were prevented.

While the duo from Pussy Riot languished in prison camps, Putin, who had returned to the Kremlin for a third term as president, cracked down on all dissent, all opposition media, on any institution or individual who dared to question his judgment or the structures of the state. He crushed the popular movement that Pussy Riot had come out of, and he even followed the Chinese example in cracking down on social media. Russia is now an immensely more isolated and oppressive place.

The battle over society—its direction, its temper, its organization, its character—is often played out on the square. But the battle rarely ends; it does not easily resolve.

OBERTO GILI