INTRODUCTION

THE INVENTION OF THE GOSPELS

When the cross upon which Christ was supposedly crucified was discovered by Empress Helena in Jerusalem, the phrase invention of the cross was used. In Latin in venire means “to be brought to light,” “to emerge.” The original meaning of invention is a coming to light of what is already there—it is both a discovery and a return.

In this sense, we might speak today of an invention of the Gospels, meaning those that were already there but lay in oblivion for many centuries, buried in the sands near Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt. Might this rediscovery of forgotten Gospels, beginning in 1945, also be an “invention of Christianity”? Might it be an occasion for a return to the sources of a tradition that is thought to have been aware of its own roots, but which in reality has been largely ignorant of them?

Some would detect here a “return of the repressed”: These sacred texts and inspired writings express and reveal the collective unconscious of a people or group. Thus these rejected Gospels reappearing in our time would be manifestations of a return of Christianity’s repressed material.

They are often called apocryphal, meaning “hidden” or “secret.” The original Greek word, as evidenced in the prefix apo-, means “under”—“underneath” the scriptures.

Similarly, that which we call unconscious or subconscious refers to what is underneath consciousness—and may secretly influence or direct this so-called consciousness. In this sense we might also speak of these as “unconscious Gospels”—for their language is in fact closer to that of dreams than of history and reason, which we have come to associate with the so-called canonical Gospels. The latter were put to effective use in building Church institutions that staked a claim, so to speak, on the entire territory of Christianity, fencing in a land that was originally open and free.

It is not my intention to set the canonical and the apocryphal Gospels against each other, nor to privilege one over the others. My aim is to read them together: to hold the manifest together with the hidden, the allowed with the forbidden, the conscious with the unconscious.

It is interesting that the Church of Rome’s current official list of approved biblical scriptures was established only in the sixteenth century at the Council of Trent. It was not until the eighteenth century that Ludovico Muratori discovered a Latin document in Milan containing a list of books that had been considered acceptable to the Church of Rome much earlier, around 180 C.E. Now known as the Muratori Canon, it represents a consensus of that period as to which books were considered canonical (from the Greek kanon, a word originally meaning “reed” and then “ruler,” or “rule”).

Thus the canonical Gospels are those that conform to the rule, and the apocryphal Gospels are those judged not to conform to it. The function of this rule is obviously to establish or maintain the power of those who made it. This was not a process that happened overnight. A significant feature of the Muratori Canon is that it allowed usage of the Apocalypse of Peter, which was later excluded from the Roman canon. Other Gospels, such as the Gospel of Peter, were considered canonical by some Syrian churches until sometime in the third century.

There are those who are disturbed by this indeterminacy in the origins of Christianity. Yet the coming to light of these ancient apocryphal writings, on the contrary, should remind us of the richness and freedom of those origins. If becoming a truly adult human being means taking responsibility for the unconsciousness, which presides over most of our conscious actions, then perhaps now is the time for Christianity to become truly adult. It now has the opportunity to welcome these Gospels, thereby welcoming into consciousness that which has been repressed by our culture. Our culture now has a chance to integrate, alongside its historical, rational, more or less “masculine” values, those other dimensions that are more mystical, imaginary, imaginal1 . . . in a word, feminine, always virginal, always fertile. The figure of Miriam of Magdala, so often misunderstood and misused, now begins to reveal the full scope of her archetypal dimension.

These Gospels were discovered by Egyptian fellahin less than forty miles north of Luxor, on the south bank of the Nile, in the area of Nag Hammadi at the foot of the Jabal-at-Tarif, in the vicinity of the ancient monastic community of Khenoboskion. It was there that some of the earliest monastic communities of St. Pachomius’s order were founded. This collection of manuscripts must have been buried sometime during the fourth century C.E. Thus it was apparently a group of orthodox monks who saved these texts, suspected of being heretical, from destruction.

We must bear in mind the context of theological, and especially Christological, crises that tormented the Christianity of this era. These monks may have buried these priceless texts in order to protect them from the inquisition by the Monophysite hierarchy, which claimed that Christ has only one nature: the divine. His humanity, the hierarchy said, was only a passive instrument used by the divinity. In contrast to this, orthodoxy maintained that Jesus Christ was both truly God and truly human—meaning he was a fully human being, with a sexual body, a soul, and a spirit (soma, psyche, nous). His intimacy with Miriam of Magdala was evidence of this fullness.2

May it have been that these texts were threatened not only by elements of the orthodoxy, as has often been claimed, but also by the Monophysites, who were shocked by certain details evoking the incarnation of the Word with a realism that was too explicit for them? This human body that spoke and taught was also a body that loved—and not merely with a chaste platonic love, but with all the sensual and psychic presence of a biblical love.

THE GOSPEL OF PHILIP

Most of the books of the Nag Hammadi codices are Coptic translations of Greek originals. The Gospel of Philip is a part of Codex II, the most voluminous manuscript in the library of Khenoboskion. The papyrus measures roughly 11 inches long and between 5.5 and 6 inches wide; and the text is 8.5 inches by 5 inches. Each of its 150 pages contains from 33 to 37 lines, whereas the other manuscripts have no more than 26 lines per page. In addition to the Gospel of Philip, Codex II contains the Gospel of Thomas, a version of the Apocryphon of John, the Hypostasis of the Archons, an anonymous writing known as “The Untitled Text” (and sometimes as “The Origin of the World”), the Exegesis on the Soul, and the Book of Thomas the Contender.

The Gospel of Philip was inserted between the Gospel of Thomas and the Hypostasis of the Archons. A photographic edition of Codex II was published by Pahor Labib,3 with the Gospel of Philip appearing on plates 99–134. A first translation was made by H. M. Schenke,4 who divided the Gospel into twenty-seven paragraphs. Although this division has been debated (E. Segelberg, R. M. Grant, J. E. Ménard), I have found it useful for this edition. It presents the Gospel of Philip as a kind of garland of words no less enigmatic than those of the Gospel of Thomas, and more elaborate, because they are certainly of a later date than the text of Thomas. Several other translations of this Gospel have appeared in German and in English (R. M. Wilson, R.-C. J. de Catanzaro, W. C. Till, Wesley Isenberg). To my knowledge, the only previous French translation is that of my colleague Jacques Ménard, of the University of Strasbourg.5

Opinions are divided as to the dating of this Gospel. Giversen and Leipoldt date it to as late as the fourth century. This is unlikely, for it would mean that it disappeared only a few years after it was written. Furthermore, fragments of this text are quoted in previous writings before the third century. I follow Puech’s more authoritative dating of approximately 250 C.E. If it is true, as most scholars believe, that this Coptic version is a translation of an earlier Greek text, then it would push back the dating of the original to around 150 C.E. This Gospel poses the same problem as that of Thomas: Being a compilation of passages, we have no means of assigning all of these logia to a single date. We must deal with the fact that the evangelic flavor of certain passages contrasts with others (no doubt of later date) that have a more gnostic character. This is not to assign a lesser value to these later passages, for age alone does not confer an automatic certificate of authenticity or orthodoxy. Like all texts considered to be “inspired,” the Gospel of Philip is witness to the diverse influences in which the cultures and beliefs of an era mingle. Such diversity always informs the supposedly perennial sources of inspiration.

In this presentation I have followed Professor Jacques Ménard’s arrangement of Codex II (indicated by the page number at the top of each page of Coptic text), plus that of Dr. Pahor Labib’s photographic edition (indicated by the plate number at the top of each page of Coptic text).

The arrangement of the passages in this translation follows that of H. M. Schenke. I have also found it useful to employ a special numbering of the passages from 1 to 127 to facilitate references to logia.

It would be hard to overemphasize the difficulties involved in the translation from the Coptic of these often sibylline texts. Professor Ménard drove himself to the point of risking his physical and mental health while working on them. I often diverge from him in both translation and interpretation of certain passages, for my concern has always been to find a meaning in these logia, even if it sometimes requires a departure from philological literalism. An archaeologist is required only to make an inventory of the broken fragments of the vase; but the hermeneutist must at least imagine, if not establish, how the vase was used.

There have been a number of more or less serious presentations of these puzzling texts. But when we have been used to laboring within the confines of archaeological and philological reductionism, who would be so bold as to attempt to elucidate their meaning to discover how they might be a source of inspiration for contemporary readers, just as they were for readers of the early centuries of Christianity? The problem with all texts bearing the name Gospel is that we no longer listen to them as Gospels—that is, as good news, as liberating teachings for human beings of all times. Instead we read them as historical documents, curious dead words of the past that are of interest primarily to scholars. Above all, we must seek to find an alive and enlivening meaning in them, as in all inspired scriptures.

With more honesty than modesty, I must admit that the translation presented here falls into the category of an essay rather than a definitive version. I hope that skilled and patient researchers will find it useful in future efforts with this text.

I have learned that to translate is always to interpret. This is where the “passion” of a text lies. The text is subject to our interpretation, and is itself a kind of decoding that always involves the subjectivity of a Logos that has been heard, or perhaps only thought. We still do not know what Yeshua really said. We know only what a number of hearers and witnesses have heard. Scripture consists of what has been heard, not what has been said.

PHILIP

Like the Jews in their diaspora, the Christian Jews (or Judeo-Christians) made great efforts to conserve their threatened traditions by putting them into writing. These texts often claimed to have the stamp of authority of one or another of the primary evangelists from Israel and its diaspora: Peter, James, John, Philip, and so forth.

In the ancient world, the concept of literary property was radically different from what it is now. An author who wrote under the name of an apostle was considered to be performing an act of homage, not an act of forgery. Pseudepigrapha, the technical term now used to describe this process, was commonly practiced. The Gospel of Philip is pseudepigraphic in this sense, like most of the other Gospels.

Why was the patronage of Philip evoked for this collection of rather long and mysterious writings? In Greek, the name Philip means “lover of horses.” In ancient times, the horse was often a symbol of noble lineage, as well as of freedom.

In the canonical Gospels the name Philip is cited on several occasions:

The next day [after the baptism of Yeshua in the Jordan], John the Baptist was still there with two of his disciples. Seeing Yeshua pass, he said: “This is the Lamb of God.” Andrew and John heard him and went to Yeshua. Seeing that they were following him, Yeshua turned around, saying: “What do you seek?” They answered: “Master, where are you staying?” He said to them, “Come and see.” They went to see, and stayed with him.

The next day Yeshua wished to return to Galilee. He met Philip and told him: “Follow me.” Philip was from Bethsaida, the city of Andrew and Peter.

Meeting Nathaniel, Philip said to him, “We have found the one written about by Moses in the Law, and by the prophets; he is Yeshua, the son of Joseph of Nazareth.” Nathaniel answered him: “What good can come out of Nazareth?” Philip told him: “Come and see.”6

Philip, a disciple of John the Baptist, was thus the third to be called by Yeshua, and quickly became a disciple. He used the same words that Yeshua had used in speaking to Andrew and John: come, leave, and see—look, contemplate, discover.

Philip subsequently takes his place on the list of twelve apostles called by Yeshua. According to Matthew 10:3 and Luke 6:14, he is named as the fifth, just after John. Mark 3:18 lists him after Andrew. In the Acts of the Apostles, after the departure of Judas Iscariot, Philip is named as the fifth among the eleven, just before Thomas. Yeshua seems to have “tested” his faith before accepting him, just prior to the multiplication of the loaves and fishes:

Lifting up his eyes, Yeshua saw a large crowd approaching him, and said to Philip: “Where will we buy enough bread to feed all these people?” He said this to test him, for he knew well what he was going to do. Philip [speaking as a knowledgeable man] replied: “Two hundred dinarii would not buy enough bread for each person to have a little of it.”7

Shortly before the Passion, as John later recounts, Yeshua had already gone to Jerusalem, and was visibly close to Philip:

Among those who came up to worship during the feast were several Greeks. They came to Philip [his Greek name would have facilitated this], who was from Bethsaida in Galilee, and asked him: “Sir, we wish to see Yeshua.” Philip went to tell Andrew, and they both went to tell Yeshua. Yeshua said to them: “The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified.”8

Later, during the conversation between Yeshua and his friends at the Passover meal, Philip is again prominent:

“If you knew me, you would also know my Father. But henceforth, you will know him, and you have seen him!” Philip said to him: “Lord, show us the Father, that will suffice us.” And Yeshua answered him: “I have been with you this long, Philip, and you still do not know me? Whoever sees me, sees the Father. How can you say, ‘Show us the Father’? Do you not know that I am in the Father and that the Father is in me? . . . Believe me: I am in the Father, and the Father is in me.”9

Philip has been called to contemplate, like Thomas, “the One who is before his eyes.” He is called to discover his Teacher and, through him, every human being, as a Temple of the Spirit, the abode of the Father. The river cannot exist without its Source. It is by plunging into the river that one can know the Source, which is God. Although “none has ever seen Him,” all that exists is witness to God’s existence. None has ever directly contemplated the Source of life, yet the smallest act of love and creation is witness to his presence. It is by living that one discovers life. It is the Son in us who knows the Father; the Father of Yeshua is also our Father. Like John, Philip is invited to become the evangelist, or the messenger of the incarnation.

Philip also appears in the Acts of the Apostles. The Teacher had led him to discover the presence of the Principle (the Father) in all its manifestation (the Son); now he has progressed to the point of understanding, from reading the scriptures himself, that Yeshua is the hoped-for Messiah. This is what he teaches the Ethiopian whom he meets on his way:

However, an angel of the Lord addressed Philip, saying: “Arise, and go south, on the road which goes down from Jerusalem to Gaza, in the desert.” Philip arose and left. Then he saw an Ethiopian eunuch, a minister and guardian of the treasure of Queen Candace of Ethiopia, who had come to Jerusalem to worship in the presence of YHWH.

Returning home, he was seated in his chariot, reading the prophet Isaiah.

Then the Spirit said to Philip: “Go forward, and join him in his chariot.” Philip approached, and heard that he was reading from the prophet Isaiah. He asked the man: “Do you truly understand what you are reading?”

“How could I, without someone to guide me?” the man answered. And he invited Philip to come up and sit with him.

Now the passage which he was reading was this one:

“Like a sheep he was led to the slaughter,

and like a lamb silent before its shearer,

so he does not open his mouth.

In his humiliation justice was denied him.

Who can describe his generation?

For his life is taken away from the earth.”

The eunuch asked Philip, “About whom, may I ask you, does the prophet say this, about himself or about someone else?” Then Philip began to speak, and starting with this scripture, he proclaimed to him the good news about Yeshua. As they were going along the road, they came to some water; and the eunuch said, “Look, here is water! What is to prevent me from being baptized?” He commanded the chariot to stop, and both of them, Philip and the eunuch, went down into the water, and Philip baptized him. When they came up out of the water, the Spirit of the Lord took Philip away; the eunuch saw him no more, and went on his way rejoicing. But Philip found himself at Azotus, and as he was passing through the region, he proclaimed the good news to all the towns until he came to Caesarea.10

Here, Philip appears as scriptural hermeneutist, and as baptist. Both of these qualities recur in the Gospel that bears his name. It is also interesting that the person whom he teaches is an Ethiopian royal official. Can it be mere coincidence that it is in Ethiopia that we find, even today, richly ornamented crosses with a representation in the center of a man and a woman joined closely together? For this is one of the most important themes of the Gospel of Philip: the union of man and woman as revelation of the Love of the creator and savior.

Philip is also the apostle of Samaria, where his teaching was accompanied by signs and wonders rivaling those of Simon Magus.

Philip went down to the city of Samaria and began proclaiming Christ to them. The crowds with one accord were giving attention to what was said by Philip, as they heard and saw the signs that he was performing. For in the case of many who had unclean spirits, they were coming out of them shouting with a loud voice; and many who had been paralyzed and lame were healed. So there was much rejoicing in that city.

Now there was a man named Simon, who formerly was practicing magic in the city and astonishing the people of Samaria, claiming to be someone great; and they all, from smallest to greatest, were giving attention to him, saying, “This man is what is called the Great Power of God.” And they were giving him attention because he had for a long time astonished them with his magic arts.

But when they put their faith in Philip preaching the good news about the kingdom of God and the name of Jesus Christ, they were being baptized, men and women alike. Even Simon himself believed; and after being baptized, he did not leave Philip, amazed as he was by the great miracles that he saw taking place.11

Philip also appears as a greatly venerated figure in the so-called apocryphal texts. The Pistis Sophia reminds us that “Philip is the scribe of all the speeches that Jesus made, and of all that he did.”

According to historians, all that we can be sure of is that Philip probably preached in Syria and in Phrygia, around the Black Sea, and that he was probably martyred or crucified in Hieropolis. In his ecclesiastical history, Eusebius of Caesarea (V, XXIV) quotes a letter from Polycratus, bishop of Ephesus, to Pope Victor (pope between 189 and 198):

Great luminaries lie buried with their fathers in Asia, sleeping the sleep of death. They will arise on the day of the coming of the Lord, the day when he comes amidst the glory of the heavens, when he awakens all the saints; Philip, one of the twelve emissaries, lies with his fathers in Hieropolis, and with two of his daughters.

THE MAJOR THEMES OF THE GOSPEL OF PHILIP

What interest is there in translating and studying these often obscure and suppressed texts of the origins of Christianity? First, there is their historical significance. A minimum of honesty demands that we endeavor to know where we come from, what are our sources and our points of reference.

What are the sources and founding texts of the established denominations, of Christianity, of our civilization itself?12 Christianity is a religion that is little known, if not unknown altogether, and this applies especially to its origins. What we know about it is mostly the history of its institutional churches and their great achievements, but also of their wars, Crusades, and sometimes their obscurantism and their inquisitions.

To reach into Christian origins is to find ourselves in a space of freedom without dogmatism, a space of awe before the Event that was manifested in the person, the deeds, and the words of the Teacher from Galilee. There is an awe and a freedom in interpreting these deeds and words as a force of evolution, transformation, and Awakening for everyone, as well as for those who believe in him.

From an anthropological13 point of view, these Gospels remind us of the importance of the nous, that fine point of the psyche which is capable of silence and contemplation, as mentioned in the Gospel of Mary Magdalene. They also remind us of the importance of the imagination.

In his book Figures du pensable (Figures of the Thinkable), Cornelius Castoriadis points out that it is imagination that really distinguishes humans from other animals. As we now know, the latter are capable of thought, calculation, language, and memory; but “human beings are defined above all, not by their reason, but by their capacity of imagination.”14 Imagination is at the deepest root of what it means to be human: Our societies, institutions, moral and political norms, philosophies, works of art, and also what is now called science—all of these are born of imagination.

This recognition of imagination gives rise to a momentous idea: Human beings and their societies can change. For Castoriadis it was the ancient Greeks who first realized the imaginary nature of the great meanings that structure social life. From this realization arose the science of politics—in this sense, the questioning of existing institutions, and changing them through purposive collective action. It also gave birth to philosophy—in this sense, the questioning of established meanings and representations, and changing these through the reflective activity of thought. To politics and philosophy we should add poetry and spirituality, in the sense of their questioning of reality supported only by sensory experience and reason to the exclusion of intuition and feeling—in other words, the objective world stripped of a Subject who perceives it or, more exactly, who interprets it and tells its story. There is neither human story nor cosmic story without the presence of imagination to speak it.

When this faculty of imagination is not kept alive, there is no more story to be told, and institutions begin to stiffen and become dogmatic. Their objectifications then take on the quality of absolutes. When imagination becomes stuck or frozen, creation and poetry are no longer possible, and this also closes the door to democratic processes as well the arts and sciences. If people lack imagination, how can they find solutions to the challenges of life?

Thus one of the functions of these inspired texts is to stimulate our imagination—or, more precisely, our power of interpretation. If, as Sartre said, human beings are condemned to be free, then it is because they are condemned to interpret. Neither in the world nor in books do we find anything with a built-in meaning. It is up to human beings to give things meaning and thereby participate in the creative act.

The Gospel of Philip affords us an opportunity for reflection, imagination, and meditation regarding certain aspects of Christianity that are sometimes hidden. The hermeneutic stimulation of this recently discovered text has at times been too strong for some, resulting in excessive and self-indulgent interpretations. For this reason, I have thought it wiser to return this Gospel to its context, and to relate it to the traditions that are its source: the Judaic tradition and the earliest forms of Christianity that grew out of it. This “orthodox” reading is quite distinct from other interpretations that have so far been offered by major commentators. It differs notably from that of my colleague Jacques Ménard, who attempted to make this text fit into the narrow category of Gnosticism, in particular Valentinian Gnosticism. Of course I do not deny such a gnostic influence—the text’s numerous terms influenced by the Syriac language testify to it, and we know that this cultural milieu was the matrix of the related currents of Mandaean and Manichean beliefs.

The themes proposed by this garland, or pearl necklace, as I have described this Gospel, are numerous. Like the individual pearls in a strand, each logion shines in its own way and could inspire a long commentary. In the framework of a shorter book, we are limited to only a few of them that seem particularly potent as invitations to deeper questioning and as challenges to certain habitual and preconceived notions.

We recall Peter’s question in the Gospel of Mary Magdalene:

How is it possible that the Teacher talked

in this manner, with a woman,

about secrets of which we ourselves are ignorant?

Must we change our customs,

and listen to this woman?15

Such a question also applies to certain logia of the Gospel of Philip. Must we change our habitual ways of looking at conception, birth, and relations between man and woman? Must we reconsider our entire image of the Christ, of the real nature of his humanity and his relation to women, especially to Miriam of Magdala?

Is sexuality a sin, a natural process, or a space of divine epiphany, a “holy of holies”? These are all themes for which we shall sketch out interpretations here, placing them in resonance with Jewish tradition. But we must also consider other themes that are no less important and just as inspiring for reflection. In logion 21, for example:

Those who say that the Lord first died,

and then was resurrected, are wrong;

for he was first resurrected, and then died.

If someone has not first been resurrected, they can only die.

If they have already been resurrected, they are alive, as God is Alive.

This reminds us that Resurrection (Anastasis in Greek) is not some sort of reanimation. As the apostle Paul pointedly mentioned in his letter to the Corinthians: “Flesh and blood cannot inherit the Kingdom of God.”16

The Gospel of Philip invites us to follow Christ by awakening in this life to that in us which does not die, to what St. John called eternal Life. This Life is not “life after death,” but the dimension of eternity that abides in our mortal life. We are called to awaken to this Life before we die, just as Christ did.

The apostle Paul further points out that it is not our biological-psychic body that resurrects, but our spiritual body, or pneuma in Greek.17

What is this so-called spiritual body? Is it not already woven in this life, from our acts of generosity and the giving of ourselves? For the only thing that death cannot take from us is what we have given away. The Gospel of Philip emphasizes this power of giving, this capacity of offering that the soter (Greek for “savior”) has come to liberate in us. It is this “body given in offering” that is our body of glory, our resurrected being.

It was not only at the moment of his manifestation

that he made an offering of his life,

but since the beginning of the world that he gave his life in offering.

In the hour of his desire,

He came to deliver this offering held captive.

It had been imprisoned by those who steal life for themselves.

He revealed the powers of the Gift

and brought goodness to the heart of the wicked.18

As in the other Gospels, we find this metaphysics of the Gift, or agap , which resides in the very heart of Being, and which the Teacher unveils through his words and his acts.

, which resides in the very heart of Being, and which the Teacher unveils through his words and his acts.

Another important theme showing a kinship between this Gospel and that of Thomas is the idea of non-duality. Some have found a distinctly Eastern flavor in this logion:

Light and darkness, life and death, right and left, are brothers

and sisters. They are inseparable.

This is why goodness is not always good,

violence not always violent, life not always enlivening,

death not always deadly.19

Such words offer a challenge to many forms of education and conditioning, but also to political attitudes. In politics it is surely unwise to separate good and evil by too sharp a division: One never occurs without the other, like day and night. This also recalls the parable of the good seed and the unwanted seed in chapter 13 of Matthew: To root out one is also to destroy the other.

Instead, we must wait for the time of harvest, meaning the time of insight. We would so much like to be pure and perfect, mistaking ourselves for God, who alone knows the ultimate meaning of good and evil. Might this be the original mistake, the original pretense or self-inflation, the cause of all kinds of suffering, of hasty judgments and exclusions? Was not Christ himself rejected and crucified by people who considered themselves just?

The Gospel of Philip reminds us of that humility, which is liberating. It is sometimes in the name of the good that the greatest evil is done, and the bloodiest and most unjust crimes are committed in the name of God and his justice. To face this fact should deliver us from fanaticism. We must accept the truth that even the best actions are never performed without at least some bad consequences. It is from the same pollen that the bee produces both honey and venom. Both the saint and (unfortunately) the inquisitor quote the same Gospel passage.

As long as we use words, we will have evils, according to the Gospel of Philip:

The words we give to earthly realities engender illusion, they turn the heart away from the Real to the unreal. The one who hears the word God does not perceive the Real, but an illusion or an image of the Real.

The same holds true for the words Father, Son, Holy Spirit, Life, Light, Resurrection, Church, and all the rest. These words do not speak Reality; we will understand this on the day when we experience the Real.

All the words we hear in this world only deceive us.

If they were in the Temple Space [Aeon], they would keep silent

and no longer refer to worldly things,

in the Temple Space [Aeon] they fall silent.20

This silence is that of the apophatic, contemplative theology that continued to develop in the following centuries:

Of God, it is impossible to say what he is in Himself, and it is more proper to speak of God by denying everything. Indeed, he is nothing that exists. This is not to say that he cannot be in some sense, but that he is above everything that is, above being itself.21

In his Apologia, II, St. Justin (100–165 C.E.) says that the terms Father, God, Creator, and Lord were not divine names, but names for the blessings and works of the divine.

Though it is good to be silent, it is still necessary to speak. Here, too, the Gospel of Philip avoids the trap of “either/or” dualism:

The Truth makes use of words in the world

because without these words, it would remain totally unknowable.

The Truth is one and many,

so as to teach us the innumerable One of Love.22

We are in the world, and this world is one of words and misunderstandings. We must nevertheless try to make ourselves heard, if not understood. This is what the Gospel of Philip invites us to do in dealing with subjects that were undoubtedly the source of much misunderstanding in his times, as they still are today.

THE SACRED EMBRACE, CONCEPTION, AND BIRTH

Without trust and consciousness in the embrace, there is nothing “sacred.” There is only release, desire-fulfillment, and biological wellbeing. Procreation is possible, but not creative engendering and conception. This theme in Philip has roots in the Jewish tradition and is developed quite explicitly in the later writings of the Kabbalah.

In kabbalistic literature, the manner of procreation is emphasized as being an essential link between a society and its ultimate destiny. Body and mind are equally involved in the act, to the point that the “spark” of divinity is said to implant itself in the matter of engendered bodies via the movement of thought of the parents during their moment of union. It is as if this thought had in itself the power to incarnate—to employ a word overly rich in implications—the divine in the heart of engendered bodies, and thus to perpetuate a genealogical lineage of altogether extraordinary quality.23

The Gospel of Philip distinguishes birth from conception. Some children are well born but poorly conceived; conception is linked with imagination and desire, with an encounter between two beings, not merely two appetites. This is why logion 112 claims:

A woman’s children resemble the man she loves.

When it is her husband, they resemble the husband.

When it is her lover, they resemble the lover.

It is possible to procreate children (through impulse and chance) without having conceived them; and they can be conceived in different ways. There are troubled or impure conceptions (i.e., the result of egocentricity or selfish aims). There are also immaculate conceptions, with pure intentions (i.e., giving freely, an expression of creative generosity, a child desired for itself ).

There is also a decisive role played by desire, imagination, and the thoughts of the parents regarding their future child as a member of a holy people in either the inner or the outer sense of that term. An intimate relation founds an intimate genealogy, which ultimately depends on intention and desire more than on any historical or juridical status.24

Compare the above with the following passage from the beginning of logion 30 of the Gospel of Philip:

“All those who are begotten in the world

are begotten by physical means;

the others are begotten by spiritual means.”

Again, the resonance between this Gospel and the later Jewish tradition is striking. The physical act of love harbors a secret that has serious implications for the whole problem of a “chosen” or “holy” people, or a Kingdom of God. And the question of our possible membership in such an elect turns out to have nothing to do with the family or ethnicity to which we belong. Instead, it has to do with the quality of trust and consciousness in the embrace, which makes us children of the nuptial act, icons of the union.

In the thirteenth-century Letter on Holiness, attributed to Rabbi Moses ben Nahman,25 this theme recurs:

The Letter on Holiness, or Iggeret ha-Kodesh, is only one of several titles by which this work has been known. No doubt it is the most widely-known, but surely the most evocative of these titles is The Secret of Sexual Relations. This shows the real subject matter of the letter, but his main concern is to bring holiness—divine life—into the very heart of the intimate act between couples. What is at stake in this concern is very crucial: nothing less than the reproduction of Israel as a “holy people,” according to the Biblical expression. How to give birth to children of a holy people, to Jews belonging to the Israelite community, is not a question with an obvious answer. The attempt to answer it must not go astray in a fog of legalistic rules defining inheritance and kinship, such as a Jew being defined as a child born to a certain person, or worse yet, enthno-genetic theories that define Jews as those of certain ancestors, and so forth. We know something about how one becomes a holy person; there exists a whole panoply of rules and disciplines for this. But for the author of the Letter on Holiness, to be born holy, to be born as a member of the people of Israel, requires a special attitude of the parents during the crucial moment that determines the form of the embryo: the sexual act. This holiness cannot be conferred by the mere transfer of hereditary traits. Nor does it have anything to do with the child’s status in the social, juridical, or religious order. Education plays no role yet. The entire significance of a “holy” lineage hinges on a voluntary, conscious act of love and spiritual meditation involving the parents—plus a few clinical precautions regarding the act of intimacy. But it is made clear that this intimate transmission of essential Judeity is totally out of the control of any social identity norms. No human tribunal is capable of judging mystical “intentions.” In this way, there emerges an Israel-being which eludes any scholarly definition. Consequently, the simple fact of being a Jew partakes of mystery: The secret of being Jewish is how one was conceived, not how one was born.26

Instead of the usual moral or clinical point of view, often accompanied by rationalizing or repressive tendencies, the Letter on Holiness treats the sexual act as belonging to the divine realm. It accords it the status of an act of theophany, exactly as does the Gospel of Philip. The sacred scriptures that societies have chosen to accept as references have undoubtedly had enormous influences, not only on the history of theology, but also on social behavior and mores—and the rejection of certain other scriptures has had immeasurable consequences.

Charles Mopsik is particularly explicit on this point:

The idea of God that monotheistic religions have imposed upon people seems to exclude any reference to sexuality as a way of approaching or experiencing the divine. Moreover, the concept of the unique God as an all-powerful Father, with no feminine partner, has formed the consensual basis of ordinary theological discourse. This has deeply influenced Western philosophy and the metaphysics that has grown out of it. These mental frameworks and representations have had all kinds of consequences for Christian and Islamic history and civilization, as well as for Judaism. These ideas have penetrated so deeply into people’s minds that they do not realize they are the fruit of a particular religious ideology, and far from axiomatic. The inability of contemporary believers and non-believers to free themselves from these structures is partly due to the fact that these religious and philosophical systems have proclaimed their concept of an asexual or unisexual God as the only reasonable one, and have relegated all others to the category of mythology. They pretend to be the sole inheritors of the biblical tradition, and jurists and theologians of the three monotheistic religions see differing conceptions of divinity as dangerous deviations.27

Yet at the origins of Christianity, in the heart of the Jewish communities from which it arose, another voice had made itself heard:

“The mystery which unites two beings is great;

without it, the world would not exist.”28

That passage from Philip resonates with the biblical tradition: In the beginning, as Genesis says, YHWH created male and female in his own image. Hence it is neither man nor woman that is in the image of God, but the relation between them. Philip also resonates with the Western philosophical tradition:

There is a certain age at which human nature is desirous

of procreation—procreation which must be in beauty and not in

deformity; and this procreation is the union of man and woman, and is

a divine thing.29

This may come as a surprise to those who associate Plato with readings that cast suspicion on “the works of the flesh.” But we must also point out that equally divergent interpretations have arisen from readings of Genesis.

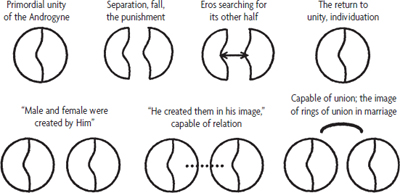

Some have seen Plato’s teaching as an evocation of the androgynous nature of humanity—at once male and female—a kind of primordial wholeness for which we have a nostalgic longing. Erotic love would thus appear to be a desperate yearning for our missing half. In Greek mythology and thought, the separation of man and woman is seen as a punishment. In Hebrew mythology and thought, however, this same separation is seen as a blessing and gift of the Creator (for example, the passage from Genesis, “He saw that it was not good for man to be alone”). Sexual differentiation is even seen as an opportunity to gain deeper knowledge of the creative source of all that lives and breathes.

The goal of a sexual relationship is not merely to regain our missing half, thereby gaining access to individuation, or to our original androgynous nature. That part of ourselves seeks its other half is really a kind of self-love; there is no access to otherness here, only a sort of inward differentiation, which is deemed painful and unfortunate.

In the Hebrew tradition, as in the Gospel of Philip, love is more a seeking of one wholeness for another wholeness. It is born not of lack, of penia, but of pleroma, an overflowing toward otherness.

A human being is born either male or female, but he or she must become a man or a woman—not just mature biologically, but become a person, a subject capable of meeting another person or subject, in a love that is not needy or demanding. Trust and consciousness in the embrace is the echo of this love.

Here is how we might symbolize the Greek and the Hebrew views:

Certain authors of the Hebrew tradition trace this encounter all the way back to two beings who are sexually differentiated but share a single soul, or a single breath, before birth itself. This is a metaphysical way of emphasizing the fact that we were created to form a couple, through which we experience the epiphany of the presence (shekhina) of YHWH.

In his book on “the secret of how Bathsheba was destined for David since the six days of the beginning,” Rabbi Joseph Gikatila writes:

And know and believe that at the beginning of the creation of man from a drop of semen, the latter comprises three aspects: his father, his mother, and the Holy Blessed-Be-It. His father and mother shape the form of the body, and the Holy Blessed-Be-It shapes the form of the soul. And when a male is created, his feminine partner is necessarily also created at the same time, because no half-form is ever created from above, only a whole form.30

Rabbi Todros ben Joseph HaLevi Abulafia (1222–1298) also said:

Know that we have in our hands a tradition which says that the first man had two faces (partsufim), as Reb Jeremiah said . . . ; and know clearly that all the parts of the true tradition (kabalah), taken as a whole and in their details, are all built on this foundation. They revolve around this point, for it is a profound secret which mountains depend upon . . . ; according to the initiates of the truth of which the tradition is truth, and of which the Teaching (Torah) is truth, the two verses in question do not contradict each other: male and female were created by Him; and in the image of God he created them (both from Genesis 1:27). The two verses are one. He who knows the secret of the image, of which it is said: in our image in our likeness (Genesis 1:26) will understand. . . . I cannot explain it, for it is not permitted to put this thing in writing, even indirectly, and it is to be transmitted only by word of mouth to upright men, from the faithful to the faithful, and only chapter titles and generalities are to be transmitted, “for the details will tell themselves.” These last words are borrowed from the formula of Haguira Ilb on the rules for transmission of the secrets of the Maaseh Merkaba (Workings of the Chariot), and they are of great interest to us, inasmuch as they clearly show that the masculine/feminine duality is the foundation of the Kabbalists’ concept of the divine Chariot. Moreover, the Kabbalah as a whole is considered to be founded on the secret of this dyad. Thus sexual difference characterizes the human soul, the “image” in which it was created, as is the divine realm which is its model.31

Thus both in the Jewish tradition and in the Gospel of Philip, the love relationship is not to be used for our own fulfillment, for the relationship itself is our own fulfillment, and the revelation of a third term of love, between lover and beloved. This third term is the source of differentiation as well as of union. The biblical tradition calls it God, and the evangelical tradition calls it pneuma, or the Holy Spirit, the breath that unites two beings.

This theme of the union of two breaths turns out to be especially important in the Gospel of Philip.

THE BREATH THAT UNITES: THE KISS OF YESHUA AND MIRIAM

The Teacher loved her [Miriam] more than all the disciples;

he often kissed her on the mouth.32

The many reactions aroused by this logion, which I have previously discussed in The Gospel of Mary Magdalene, recall a strange state of affairs: Whereas Yeshua has often been depicted with a young man resting his head on his breast (and such images have not been without effect on the behavior of the clergy), it is practically unimaginable to paint him in a pose of intimacy with a woman. It is as if such contact with a woman would detract from the perfection of his humanity and his divinity, though the very opposite is the case. How many times will it be necessary to repeat the adage of the early church Fathers: “That which is not lived is not redeemed”? In other words, that which is not accepted is not transformed?33

Was Jesus Christ fully human, a “whole man” (as Pope Leo the Great said, Totus in suis, totus in nostris), or not?

The doctrine of the Council of Chalcedony says so: “Christ is at once perfect (totus) in his divinity and perfect (totus) in his humanity.” Thus to depict him as sexually defective should amount to blasphemy. So why all the fuss?

A serious consideration of this subject is required. The Gospels discovered not so long ago at Nag Hammadi invite us to do so. It would undoubtedly help us to be free of the guilt, unhappiness, and degradation that have surrounded what, if one takes the biblical texts seriously, is a means of knowing and participating in the holiness of God himself.

St. Odilon of Cluny uttered the following words. How was this possible?

Feminine grace is nothing but blood, humors, and bile . . . and we who recoil at the touch, even with the tips of our fingers, of vomit and excrement, how could we therefore desire to hold in our arms the very sack of excrement itself?

How could anyone desire to canonize such hatred and contempt?

In any event, the Gospel of Philip has Yeshua embracing Miriam on the mouth, and with love rather than disgust. We must emphasize once more that the meaning of this kiss cannot be understood apart from the Judaic and gnostic context of that era.

You must know in your turn what the ancient ones—blessed be their memory—have taught. Why is the kiss given on the mouth rather than some other place? Any love or delight that aims for true substance can express itself only by a kiss on the mouth, for the mouth serves as source and outlet of the breath, and when a kiss is made on the mouth, one breath unites with another. When breath joins with breath, each fuses with the other, they embrace together, with the result that the two breaths become four, and this is the secret of the four. This is even more true of the inner breaths (the sefirot), which are the essence of all; so do not be surprised to find them intertwined in each other, for it expresses their perfect desire and delight.34

We must also mention the kiss in the Song of Songs, as well as God’s kiss to Moses at the moment of his expiring. The Hebrew word for kiss (nashak) means “to breathe together; to share the same breath.” And the word for breath is the same as the word for spirit; this is true not only in Hebrew (ruakh), but also in Greek (pneuma) and Latin (spiritus). Thus Yeshua and Miriam shared the same breath and allowed themselves to be borne by the same spirit. How could it be otherwise?

Charles Mopsik notes that the kiss of union does not necessarily imply a sexual aspect to the relationship, though it may be a prelude to it. It is in this union that the secret is revealed, a secret that leads us to the bridal chamber. For the Gospel of Philip, as for the older Hebrew tradition, this chamber is the holy of holies.

THE BRIDAL CHAMBER, HOLY OF HOLIES

...and the holy of holies is the bridal chamber . . .

Trust and consciousness in the embrace are exalted above all.

Those who truly pray to Jerusalem

are to be found only in the holy of holies . . .

the bridal chamber.35

This logion only reinforces the resonance between this Gospel and the Letter on Holiness attributed to Nahmanides, which offers a kind of explanation:

The sexual relationship is in reality a thing of great elevation when it is appropriate and harmonious. This great secret is the same secret of those cherubim who couple with each other in the image of male and female. And if this act ever had the slightest taint of anything ignoble about it, the Lord of the world would never have ordered us to make these figures, and to place them in the most sacred and secure of places, built upon a very deep foundation. Keep this secret and do not reveal it to anyone unworthy, for here is where you glimpse the secret of the loftiness of an appropriate sexual relationship. . . .

If you understand the secret of the cherubim, and the fact that the [divine] voice was heard [in their midst], you will know that which our sages, blessed of memory, have declared: In the moment when a man unites with his wife in holiness, the shekhina is present between them.36

If this is really true, if the union of man and woman is the holy of holies where his presence (shekhina, Sophia) is manifest, the place where his breath is communicated (ruakh, pneuma), how is it possible for Pope Innocent III (d. 1216) to say, “The sexual act is itself so shameful as to be intrinsically bad,” or for one of his theologians to say, “The Holy Spirit departs of itself from the bedrooms of married couples performing the sexual act, even when it is done only for procreative purposes”?

Both Jewish tradition and the Gospel of Philip say exactly the opposite. If any wedding chamber were really abandoned by the Holy Spirit, it could only result in the birth of “animal humans” rather than beings capable of knowledge and worship of God. Hence the place of holiness has become a place of vilification, and the intimation of paradise has been reduced to a gateway to hell.

In his Meïrat Enayim, Rabbi Isaac d’Acco offers this parable:

A newborn infant was abandoned in a forest with nothing but grass and water for nourishment. He grew up, and here is what happened to him: He went to a place where people were living and one day saw a man coupling with his wife. At first he laughed at them, saying “So what is this simpleton doing?” Someone told him: “It is thanks to this act, you know, that the world continues. Without it, the world would not exist.” The child exclaimed: “How is it possible for such a base and filthy act to be the cause of a world so good, so beautiful, and so praiseworthy as this one?” And they answered: “It is the truth, all the same. Try to understand it.”37

Nahmanides adds: “When the sexual relation points to the name, there is nothing more righteous and more holy than it.” Yet it is necessary to “point to the name.” For the pure, everything is pure. Purity resides in the intention and motivation that direct the act. This recalls the previously discussed theme of the transmission of holiness as something more than biological genealogy.

The elders kept their thoughts in the higher realms and thereby attracted the supreme light toward the lower ones. Because of this, things came in abundance and thrived, according to the strength of the thought. And this is the secret of the oil of Elisha, as well as of the handful of flour and the jar of oil of Elijah. It was because of these things that our masters, blessed of memory, said that when a man joins with his wife with his thought anchored in the higher realms, this thought attracts the higher light downward, and this light settles in the very drop [of semen] upon which he is concentrating and meditating, as it was for the jar of oil. This drop thereby finds itself linked always to the dazzling light. This is the secret of: Before you were formed in the womb, I knew you ( Jer 1:5). This is because the dazzling light was already linked to the drop of this righteous man in the moment of sexual love [between his parents], after the thoughts of this drop had been linked to the higher realms, thus attracting the dazzling light downward. You must understand this fully. You will then grasp a great secret regarding the God of Abraham and Isaac, and Jacob. These fathers’ thoughts were never separated from the supreme light, not for an hour or even an instant. They were like servants indentured for life to their lord, and this is why we say: God of Abraham, God of Isaac, and God of Jacob.38

There are many other texts from the Jewish tradition that could help us to better understand the Gospel of Philip. Moshe Idel, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has already pointed out the connections between this tradition and Christian gnostic texts.

It seems certain that these texts reflect a Jewish notion of the pre-existing Temple. In the Midrash Tanhuma, regarding the reference to the royal bed in the Song of Songs, the anonymous commentator says: “His bed is the Temple. To what here below is the Temple compared? To a bed, which serves to bear fruit and increase. The same applies to the Temple, for everything that was found there bore fruit and was increased.” This allows us to conclude that a sexually nuanced perception of the holy of holies already existed in ancient Judaism. Shortly after the destruction of the temple, we find that the bridal chamber substitutes for it as a place where the Shekhina (Presence of God) resides.

The whole exercise (mitzvah) proposed by the Teacher in the Gospel of Philip consists of introducing love and consciousness into each of our acts, including the most intimate. In this way, this space-time (the world) becomes a space-temple, a place of manifestation of the presence of YHWH, the One Who Is (I am who I am, Exodus 3:14), in complete clarity, innocence, and peace.

In a future work I hope to offer a very detailed analysis of each logion of the Gospel of Philip, relating it to its Jewish, gnostic, and canonical Gospel parallels. For now, I have had to content myself with a translation of this difficult and fascinating text, along with some suggestions for possible interpretations. In this introduction I have articulated some of the questions raised by this Gospel. I have never pretended to have the answers to these questions, yet this must not lead me to deny the nearness of a source that is capable of satisfying the thirst for these answers.