At the turn of the century it was still possible to describe New Zealand as a series of settlements linked by a few railway lines and a growing network of telephone wires. The South Island enjoyed better communications than the North. By 1926, however, the North Island was booming. Where population in the two islands had been nearly equal in 1901, that of the North Island now stood at 62 per cent of New Zealand’s total. In the same period urban drift was pushing up the population of towns and cities. Auckland and its suburbs with a population of about 192,000 had grown by 185 per cent in the 25 years; Wellington, with 121,000, by 145 per cent. In the South Island only Christchurch with its population of 118,000 — a growth of 107 per cent in the past quarter century — had a comparable level of expansion.1

By 1925 the transport network in the North Island neared completion. The North Auckland main trunk line carried its first express train in 1924,2 and when Coates opened the road through the Dome Valley north of Warkworth the following year, the so-called ‘roadless north’ was finally connected with the North Island’s network of highways. The regular shipping link from Helensville to Dargaville and Matakohe entered a slow decline, and in 1947 the Harbourmaster’s office at Helensville was closed down. Elsewhere around the North Island formerly remote areas were also joining what had become a national economy. The extractive industries — gold, gum and timber — had lost their significance; supplies were exhausted. Small dairy farms appeared in previously isolated areas in the Kaipara, Waikato, southern Taranaki and eastern Bay of Plenty. Much of the flat land around Ruawai and Te Kopuru was now producing butterfat. Efficient transport links were the breakthrough for settlers who had been clearing the land and enduring little more than subsistence living.

In the cities modern suburban sprawl was a fact of life. In Auckland, Mount Eden, Onehunga, Devonport and Remuera had largely filled out by the end of the war; Kohimarama, Ellerslie, Royal Oak, One Tree Hill, Mount Roskill, Mount Albert and Westmere were the urban frontiers of 1925. Wellington had Seatoun, Miramar, Hataitai, Wadestown, Ngaio and Karori. Local authorities, banks, insurance companies and real-estate agents joined hands in this march of progress. Street lights, and then domestic power with its capacity to activate a growing range of household appliances, supported an army of electricians and equipment manufacturers. Indoor plumbing became possible as sewerage reticulation spread outwards from the centres of cities. Homes grew larger, and material aspirations seemed limitless. Younger people of the post-war generation, many of them new to city living, were ambitious to succeed. They looked for vigorous political leadership to promote greater prosperity. Older people on fixed incomes and under threat from changes to their environment and the rising cost of living anxiously sought security and stability.

A. E. Davy in the 1920s. (Alexander Turnbull Library)

By 1925 Reform and Labour were competing for the cities’ votes; the Liberals had seen their support halved at successive elections since 1914, and there was little left. Labour held the inner-city seats in the three main cities and was challenging Reform in the suburbs. Reform’s leaders had long since hit on the tactic of frightening upwardly mobile voters with assertions about Labour’s policies. In election years the Christchurch Press always labelled Labour ‘the Reds’. One Labour candidate called the device ‘the old goat’ that Reform let out to butt the voters before polling day.3

In the run-up to the 1925 election daily newspapers went to extraordinary lengths to promote the new Prime Minister. In July a London newspaper eulogised Coates. ‘Physically, [he] is a tall, lithe man, erect and soldierly in figure, whose body, compact of bone and muscle, is a stranger to fatigue. He has clear eyes, a tanned face, and a kindly mouth.’ This description was faithfully reproduced in many local papers.4 The Christchurch Press felt compelled regularly to editorialise about the Prime Minister and developed the happy knack of turning any perceived flaws into selling points. ‘He has never professed to own the gifts of the orator, who as often as not is nothing but a gasbag. … Audiences from the far North to furthest South have seen for themselves that he has something to say, and knows how to say it clearly and effectively. … He has broken most of the rules of the orthodox politician, and he has discovered that the public likes it.’5 Most dailies treated Coates as a breath of fresh air.

Reform’s campaign turned out to be a king hit. Coates: comfort and confidence; Labour: chaos, confusion and communism — these were shaken into a cocktail packing a potent punch. Never before, and seldom since, has the business community opened its cheque-books so wide to any political party Reform’s organiser, ‘a spare-built individual, quick in speech and very active’, with a passion for autocycles, a man by the name of A. E. Davy, placed many full-page advertisements in newspapers, inviting voters to take their ‘Coats off with Coates’ and extolling the virtues of ‘Coates and Confidence’, ‘Coates and Certainties’. Pictures of Coates with a rising sun behind him, and a smaller circle nearby with the words, ‘If you love New Zealand, Vote for Sound Government — Security — Progress — Vote Coates’ appeared in most papers in the country. A. S. Richards, the Labour candidate in Marsden, said that ‘in places inhabited only by a Maori, a kiwi bird and a dog’ he had seen large portraits of the Prime Minister issued by the Reform Party. John A. Lee later recalled: ‘We had the Prime Minister’s photo coming to us in the morning news, in the evening news, wrapped around sausages, wrapped around fish — indeed it was impossible to avoid the intrusion of the … photo upon your sight many times a day.’6

The Reform Party’s manifesto was released on 2 October. It was a bland statement on which the press performed what today would be called a ‘beat up’. The policy ‘is not drawn up to tickle the ears of the listeners by telling them merely pleasant-sounding things,’ said the Herald. ‘Instead, [it] pays the people the compliment of taking it for granted they have a practical, intelligent interest in the conduct of their own affairs.’7 The document talked about Empire, security, stability and equal opportunity, and went on to borrow President Coolidge’s slogan of ‘More business in Government, less Government in business’. It promised ‘sound finance’, completion of major public works, and a gradual reduction of external borrowing. There was a vague hint that customs duties might be reduced. In the centre of it all was the core of Coates’s personal philosophy; the freehold would be offered to all holders of Crown leases, although there was, as the Auckland Star conceded, no further detail about the terms of the offer. The document ended by stating that Reform’s ‘bedrock principles’ were ‘national safety and progressive development’.8

The official portrait as Prime Minister, 1925.

The National Party, as the Liberals were now called, had little new to offer. Moreover, members were compromised by their mid-year eagerness to fuse with Reform. During the campaign some National candidates praised Coates. Robert Coulter, National candidate for Tauranga and later Labour MP for Waikato and Raglan, was widely when he called Coates ‘a good sort’ and ‘a straight goer’ at the Prime Minister’s meeting in Te Aroha.9 More seasoned members of the Opposition like David Buddo of Kaiapoi were left grumbling that the Reform Government was really ‘moribund’, except for its extravagant borrowing.10

Labour leaders, on the other hand, tried hard to promote their party’s land policies in the hope they could make an electoral breakthrough into rural areas. They called their policy the ‘usehold’, but Reformers and National Party supporters alike quickly nicknamed it the ‘loosehold’.11 The more Harry Holland talked about it at election meetings, the more he came across, as the Round Table commented some months later, as the ‘man of words’ pitted against the ‘man of action’.12 Moreover, a shipping strike in Australia that spread to New Zealand waters in October, tying up several ships and angering farmers, did nothing to improve the fortunes of a socialist party linked to organised labour.

Coates, always with Marjorie at his side, travelled around the country in regal style, local candidates rushing to touch his hem. In the deep south, then in the far north, he gave overflow audiences a standard speech about the need for ‘strong and safe Government’, and called his own policies ‘liberal and progressive’. He talked of governing for all, and said he proposed to introduce a national contributory insurance scheme whereby everyone would be insured against sickness and unemployment. He promised help for large families where budgets were severely stretched.13 What his oratory lacked in eloquence was more than made up for by a generous political disposition, genial friendliness, smiles and handshakes.

When the ‘Man from Matakohe’ went north, crowds mobbed him at the Huarau station. There was much excitement when the Prime Minister called briefly at Ruatuna to visit his mother. On 17 October Coates and Marjorie arrived in Dargaville. The local paper described it as ‘Kaipara’s Red Letter Day’. As if by magic, the rain dried away and there were flags and greenery everywhere. A group of returned servicemen, ‘my own digger pals’, Coates called them, pulled the car into Dargaville while the town’s band played ‘For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow’. The mayor and councillors put on a civic reception. In the evening the largest public meeting in the town’s history cheered their MP when he mounted the stage. A piper played ‘Cock o’ the North’. Coates spoke mostly about local issues, then appealed to the audience’s ‘sense of fairness’. He told them that he wanted to develop ‘liberty, political and economical, free from class ascendancy and privilege’. He wanted to uphold ‘the principles of freedom and equality of opportunity so that the humblest member of the community could be said to carry a field marshal’s baton in his knapsack and by qualification and application be able to fit himself for the higher ranks of citizenship’. He favoured moderate economies in Government; he wanted people to be able to export, and saw it as his responsibility to ensure there were jobs.14 It was not the speech of an average Tory’, revealing as it did a more egalitarian philosophy nearer to Labour’s. Some of Coates’s colleagues acknowledged this about their leader. In Henderson during the campaign, the loquacious Parr said of Coates that he was ‘no Tory … he came from the people and was for the people; he stood all the time for justice to all sections of the community’.15

In Whangarei the crowd was so large that the overflow assembled in the Lyceum Theatre; the Prime Minister went on to address them at the end of his Town Hall meeting.16 On 2 November Coates was greeted by an ecstatic crowd of 3,000 in the Auckland Town Hall, with another 2,000 outside in Greys Avenue listening through loudspeakers. As usual he was running late, and he had almost lost his voice. His speech kept to generalities, to home, hearth and security. Next day he finished his campaign in Thames to ‘a storm of applause’.17 Coates clearly enjoyed it all, and demonstrated just the confidence and sense of security that the public was looking for. He was only beginning to realise how high were the expectations of him.

On the evening of 4 November the results flashed up on screens in the cities’ main streets. Reform had won its biggest victory in the party’s career. The Government won ten more electorates in the North Island and seven in the South Island, securing a total of 55 seats. The handful of dissidents who stood as Country Party candidates were slaughtered. After several recounts Labour finally ended up with twelve seats — five down on 1922. National reached twelve with the help of the aged Sir Joseph Ward; resolutely holding on to the label of ‘Liberal’, he made his come-back in Invercargill.18

Coates’s victory was a stunning result, almost as sweeping as Seddon’s last hurrah in 1905. The public was not yet ready to trust Labour, and opted instead for Coates’s personality and promise. The Christchurch Press called it a ‘magnificent victory’; the Northern Advocate, a victory for ‘stable government’. The Auckland Star said next day that the Prime Minister had

captured the imagination of a large section of the public. He appeals to it as a vigorous man in the prime of life, honest and direct in his dealings, approachable and breezy in disposition, and one who is not bound by convention, but has the courage to put new ideas into practice. Probably the influence is largely psychological and most voters would find it difficult to put into words.19

Behind Coates what is there? The same old pack of men who were declining with Reform through the last decade. In the Reform advertisements they were wisely kept out of the text. Reform is like a second-hand car that has been painted and is selling as brand new.20

It was an image that came to many minds over the next three years.

In the Kaipara electorate Coates had only one opponent. W. E. Barnard was a lawyer from Helensville and later Labour’s Speaker of the House. Coates’s campaign was handled in his absence by a very active committee. They staged a series of ‘village meetings’ on his behalf. Barnard scored only fractionally better than Gregory had done in 1919; the Prime Minister won 81 per cent of all votes cast, the biggest percentage obtained anywhere in the country by a Reform candidate. He lost no polling places; at sixteen of them his Labour opponent won not a single vote.21 The Reform hierarchy was cock-a-hoop. Sir Heaton Rhodes called the victory a ‘tribute to [Coates’s] personality’. Bell wrote to Downie Stewart in glee: ‘What a fine power Coates has developed and what a happy sense of proportion in politics. He has kept us free from petty recriminations such as Ward delighted in, and it is unalloyed delight to win as Coates has won.’22

After dining with the Bells on election night, Coates went round the Wellington newspaper offices addressing enthusiastic crowds assembled in front of the screens. He told them that the battle was over and that the best thing they could do was to ‘bury the hatchet’. His goal was to deliver on the promises he had made. Then he went off to celebrate with friends, getting home at 3 a.m. Next morning he was back at his desk appearing to be ‘not a whit the worse for the strenuous campaigning he had undertaken’.23 His family was soon shifting into the traditional home of prime ministers at 260 Tinakori Road, now known as Ariki Toa, or ‘home of the chief. He was there by right of election, not merely succession.

Unexpectedly large wins often have their perils. Likening the situation to Seddon’s victory of 1905 which he then had to deal with, Sir Joseph Ward pointed out a few days after the 1925 election that it was possible for a winning party to be embarrassed by its riches, an observation frequently echoed by Sir Charles Fergusson in his quarterly reports to the Dominion Office.24 With 55 seats Coates had more than twice the votes in Parliament of his combined opponents. So great was the victory that Coates could do almost anything he liked. Interest quickly settled on the personnel of Coates’s Cabinet from which Sir Francis Bell and Sir Heaton Rhodes had signalled an intention to retire. ‘Will [Coates] rise to the occasion?’ asked the editor of the Auckland Star. ‘Will he reconstruct his Ministry, dropping the “duffers” and the reactionary elements, and putting in their place the ablest and most enlightened in the party? That will be the first test. The Ministry is notoriously weak.…’25 Next day the editor added: ‘Man’s chiefest enemy is security, and wisdom scents danger when there is unanimity of praise.’ Others, including Reform’s usually uncritical supporters such as the Press, were also asking whether Coates would have the courage to move decisively, and suggested new names for the Cabinet. Generally it was Nosworthy (whom the Governor-General found boring) and Bollard who were singled out for execution.26

Coates, however, was plagued by a sentimental streak. He was a man of his word, and he had promised Finance to Downie Stewart. Stewart was now back from New York, but not yet feeling fit enough to assume Finance. He resumed his other duties, but Coates, in what Stewart called ‘his usual generous way’, allowed his colleague to defer taking over the Finance portfolio until 24 May 1926.27 In the meantime Coates delayed. Weeks ticked by, during which the public and press grew more and more restless. Early in the New Year the Herald urged reconstruction, and there was considerable speculation about the reasons for Coates’s delay.28 On 18 January the Prime Minister at last announced three new ministers. O. J. Hawken took over Agriculture from Nosworthy, and F. J. Rolleston relieved Parr of Justice and assumed Defence, which Rhodes had held for five and a half years. Rounding off the trio was J. A. Young who became Minister of Health in place of Sir Maui Pomare, whose own health was giving trouble. Sacking ministers, however, was not in Coates’s make-up. There were rumours that he wanted to dispose of Nosworthy, but he had initially been appointed in 1919 at the same time as Coates, and the fact that he had challenged him for the leadership only a few months before made demotion doubly difficult. Coates did not complete his Cabinet reconstruction until Parr went to London as High Commissioner at the end of April 1926. R. A. Wright, known around Parliament as ‘Monkey’ Wright, assumed the Education portfolio on 24 May and on 12 June 1926 K. S. Williams took Public Works from the Prime Minister, who had long signalled an intention of reducing his own work-load. As MP for the remote Bay of Plenty, Williams had more than a passing interest in better roads. All the older members of Cabinet, however, were kept on; at thirteen it was now the largest Cabinet on record. The Reform caucus grumbled publicly. The Auckland Star was scathing. ‘Week after week has passed and still these members retain their posts.’ The paper suggested that Coates was not cabinet-making, but engaging in a complex process of joinery, ‘and of an apprentice type at that’. The Prime Minister was losing his reputation for decisiveness.29

It was not just sentimentality that caused Coates to procrastinate. His caucus changed dramatically with the election of 1925. John A. Lee waspishly described the new members as ‘elderly men of Victorian sentiment … washed out of their armchairs into the House, where they … busied themselves in trying to turn the clock back’.30 There was more than a grain of truth in the comment. Of the 55 MPs now in the Reform caucus, only four were younger than the Prime Minister, who turned 48 in February 1926.31 A majority came from rural electorates, and their speeches revealed a decidedly conservative, even reactionary disposition. Many had agreed to stand before Coates became Prime Minister. Few can have had expectations of personal victory. Nosworthy and Bollard, both of them part of the older rural set, were nearer in style and temperament to the new majority in caucus than the Prime Minister himself with his liberal, tolerant, slightly State-interventionist outlook. The ‘man of action’ whose election campaign seemed to point to the future was paralysed by remnants of his party’s past.

Perceptions of indecision in high places played a part in the Government’s stunning by-election reverse in Eden in April 1926, only five months after Coates’s great triumph. When Sir James Parr resigned his seat, the Auckland feminist and City Councillor, Ellen Melville, thought her track record as a Reform candidate entitled her to the Reform nomination. However, business backers of the party, including members of the so-called ‘Kelly Gang’, insisted on the former mayor of Auckland, Sir James Gunson. The party’s organiser, A. E. Davy, endeavoured to persuade Melville to step aside. Stories reached the press of money being offered to Melville to oblige Gunson,32 who eventually won the Reform nomination. Melville decided to contest the by-election in any event: she called herself Independent Reform. Gunson paid the price. What had been expected to be an easy Reform victory turned into a fierce campaign necessitating visits from Coates to Oratia, Te Atatu, Glen Eden and New Lynn. Labour’s Rex Mason won with 41 per cent of the vote, confirming the Labour Party’s claim to be Parliament’s official Opposition, and beginning Mason’s record-breaking service as an MP.33

The press made some scathing comments about Reform’s handling of the by-election. The Auckland Star said that the Reform Party could blame no one but itself: ‘the whole business was badly managed from beginning to end, insurgency and schism have been allowed to develop and the whole position of the party … has been greatly weakened’.34 There was a perception abroad that the Prime Minister lacked the firm grip on his party’s organisation exercised in former times by Massey

The truth is that the Prime Minister lacked the political skills to capitalise on the stunning vote of confidence he had been given in November 1925. He had proved himself knowledgeable about public works and railways, issues that he had mastered since his days on the Otamatea County Council. A businesslike approach to development issues never deserted him. But when he had said often enough on the platform that he was a newcomer to politics, he meant it. Overall political management was as novel to him as the house he had just moved into. Between 1919 and 1925 his portfolios had taken him out of Wellington much of the time. Strategic thinking about how to position the Government on issues of the day had remained firmly in the hands of Bell and Massey. With Massey now dead and Bell soon on his way to London and Geneva on an extended trip, there was no one left with shrewd strategic instincts. Moreover, Coates’s own thoughts were turning more to the upcoming Imperial Conference due to begin in October in London. In January 1926 Coates had announced the establishment of a Prime Minister’s department to provide a ‘greater measure of efficiency in dealing with official matters’,35 and the Prime Minister’s Private Secretary, F. D. Thomson, was put in charge. However, the changeover seems inexplicably to have taken several months; responsibility for preparing the Governor-General’s speech for the opening of Parliament, a task consistently undertaken by Bell in the past, was overlooked until the last minute. It was then hastily cobbled together. The address that was read on 17 June was one of the thinnest on record — a Vague document’, complained one newspaper.36 The Prime Minister then failed to take the opportunity to speak during the Address in Reply and to discuss the legislation proposed for the session. This was partly due, as Downie Stewart conceded later to Bell, to the fact that the Opposition was so low in numbers that no debates could continue for long.37 However, there was a sense that Coates’s Government was still drifting, despite the message from Eden.

Complicating matters was the state of the economy. By June 1926 the Bank of New Zealand was predicting a ‘hard winter’.38 At no point in the 1920s were export prices simultaneously good for all of New Zealand’s products. By the middle of the year wool, meat and butter prices had all fallen disastrously below the levels of 1925, and the country was heading for its second trade deficit of the decade.39 Coates’s Government came under sustained attack from the Labour Opposition as unemployment steadily increased during the winter. At the end of June Holland claimed there were fifteen hundred unemployed in Auckland, and another six or seven hundred in Wellington.40 The Government took on an extra 450 men in Railways, and the Public Works Department absorbed 700 more employees. Emergency legislation empowering local authorities to borrow to provide employment was rushed through Parliament. But still the numbers out of work grew. Some argued that immigration which had brought 37,103 new migrants to New Zealand over the previous five years should cease.41 There was an ugly mood developing around the country, which Coates seemed powerless to placate. In Parliament his party, despite its huge majority, was on the defensive.

The Prime Minister did push ahead with some of the policies he had discussed during the campaign. While nothing further was heard about the national contributory insurance scheme he had bruited (it was finally dropped on the eve of the 1928 election), the freehold option was extended to virtually all tenants of Crown land. A Family Allowances Bill was introduced on 17 August. The bill was handled by Anderson, who was Minister of Pensions, but it was very much Coates’s brainchild. Allowances of two shillings per week per child were payable to a mother with three or more children, where the family income was below £4 per week. They began from 1 April 1927. A sum of £250,000 was appropriated by Parliament for the purpose. The Labour Opposition called the allowances paltry, but Coates made it clear that there could be no increase in taxes for the purpose. ‘Anything in the shape of increased taxation would be the worst day’s work we could do for the workers of the Dominion,’ he declared. He would have liked the sum payable per child to have been more generous, but said that in the present economic climate ‘it would be most unwise … to attempt anything of an extravagant nature’.42 The measure was designed to help those with large families, and was another milestone in the development of the welfare state. It drew opposition from some conservatives in the Legislative Council, and the Press and the Employers’ Federation strongly disapproved.43

Also on the list of promised legislation was the Town Planning Bill introduced on 22 July and passed on 20 August. Similar legislation had been promised for 25 years and finally surfaced at the end of the war. It was subjected to such criticism that it had been dropped. The new bill obliged local authorities of 1,000 or more citizens to introduce a rudimentary system of zoning, and gave local authorities the power to make building by-laws. It determined the minimum width of streets. Each local authority was obliged to produce a draft scheme and to submit it to a Town Planning Board no later than 1 January 1930. The bill excited much controversy. Many local authorities felt it took away their rights, and several particularly resented the powers of the board.44 Local authorities were also affected by the Local Government Loans Board Bill given a second reading on 29 July. The Prime Minister himself handled the bill and made it clear that he felt that too much money was being borrowed too easily by local politicians. The bill now required a local authority to clear any proposed loan with the Local Government Loans Board before proceeding.45 Again there was some feeling that the legislation amounted to Government intrusion on local rights.

More complicated, and even more controversial, were the issues raised by the Motor-omnibus Traffic Bill introduced at the tail end of the session. Over the years many local authorities had invested more than £6 million in tramway services, only to discover that with the improvement of roads private bus companies were undercutting the publicly provided tram services. Many of these were now running at a loss and costing ratepayers dearly. Coates wrestled with the issue in December 1925 when a set of proposed regulations was circulated. They provoked cries of anguish from private bus operators, since the regulations began with the assumption that local authority tram systems should be protected from private competition. Nevertheless, the regulations were gazetted in May 1926 under the Board of Trade Act 1919.46 Immediately doubts were raised about whether the Act allowed such regulations, and several controversies were soon entwined with each other.

A Parliamentary select committee was set up. It reported to the House that a bill should be passed. The Government now proceeded to ram such a bill through the House. In the process the whole issue became the subject of heated debate. The bill divided the country into motor omnibus districts and made the local authority, which in most instances owned the trams, the licensing authority. All bus services were required to be licensed. And any existing private bus operator could require the local authority to buy out his bus service, although there was no allowance for payment of goodwill.47

What the Government found most embarrassing was the Labour Party’s declaration of support for the bill with the words: The Labour Party stands, and always has stood, for the community service as against private service resting on a competitive basis. … Privately-owned buses cannot be permitted to enter into destructive competition with the publicly-owned tramway and bus services.’48 Had Coates become a socialist? Alexander Harris, Reform’s MP for Waitemata, clearly thought he had, and inveighed against his own Government, accusing it of creating monopolies rather than being for free enterprise. Referring to the state of affairs on Auckland’s North Shore, where a Devonport private company ran buses in competition with the tram service from Takapuna to Bayswater, Harris spoke out on behalf of the many employees of the private operator whose jobs were now endangered because the Takapuna Borough Council had been constituted the local licensing authority and clearly favoured its own tramway company. Along the way Harris suggested that the measure was intended as a payback by Government ‘to one of its friends’.49 Ministers stoutly denied the accusation, and Downie Stewart challenged Harris to leave the ranks, only to see Harris supported a few minutes later in debate by V. H. Potter, Reform MP for Roskill. A series of amendments was moved, mostly by Harris. The Government majority prevailed, but there were members from all parties on most sides of the issues. The bill had created ideological confusion and political mayhem. R. M. Burdon has written of the issue that Coates’s apparent ‘surrender to the principles of socialism’ was ‘being discussed in scandalised tones wherever two or three, who held the rights of private enterprise sacred, were gathered together’.50

The historian, John Gaudin, has pointed out that the Government was moving over ‘unsure ground’. It was facing up to the same regulatory or control issues that were plaguing other countries with expanding public and private services. Rapid urban growth, consumer demands and burgeoning free enterprise were producing cutthroat competition as well as challenges to authority, especially where public investment was involved. For many years governments had acknowledged growing difficulties but had usually stopped short of legislating. In the one session of 1926 Coates dealt with years of accumulated demands. Town planning, transport regulation, control over local bodies’ loans, joined a list of other measures such as film censorship, an extension of rent restrictions, registration of electrical wiremen, dentists, opticians, veterinary surgeons and engineers. Coates’s Government shrank from none of them, although it was difficult in times of economic downturn to explain to the public how such measures would assist in producing what was so universally sought — an economic upturn. When the session finished, editors of newspapers were left scratching their heads, too. The New Zealand Herald mourned that there had been no further progress towards tax reduction; instead there seemed to have been an extension of bureaucracy.51 It was probably as well that the Prime Minister was off to London where the issues would provide a pleasant, personal diversion from domestic preoccupations.

On the evening of 14 September 1926 after a brief farewell, Coates and Marjorie boarded the Makura in Wellington. Downie Stewart was Acting Prime Minister. Coates had two or three ‘fairly rough days’ on the way to Rarotonga, but the two of them were soon enjoying the break. Coates and Stewart communicated regularly, Stewart always contriving to have an account of affairs at home waiting for his chief at each port of call. Coates encouraged Stewart to delegate, telling him that Nosworthy, McLeod, Rolleston and Anderson would be a ‘great help’, and that ‘old Wright and Williams will soon be a source of strength and help to you’. Pomare could be relied on to handle detail ‘quite well’. Above all, Coates was anxious to have all proposed appointments to boards cleared with himself.52 Stewart, in turn, was worried about the continuing high levels of unemployment, and intended subsidising work out of revenue rather than loan moneys, which are supposed to bear interest’.53 For the most part, however, he simply ran a ‘holding operation’ while the Prime Minister was away, talking and corresponding frequently with the Governor-General, smoothing over difficulties where possible, and referring thorny issues to London.

The Coateses arrived in New York from San Francisco in the first week of October. They boarded the Majestic on 9 October along with several other people with an interest in the Imperial Conference, including Sir James Craig, Ulster’s Premier, and some Australians and South Africans. On the 14th they arrived in Southampton to a mayoral welcome. Coates declared his pleasure at being in the ‘homeland’.54 Next evening they reached Waterloo Station where they were met by a party of 20 New Zealanders, including Sir James Parr, Sir Thomas Mackenzie and Sir Alexander Godley. They were whisked to the Hotel Cecil in the Strand. It became their headquarters for the duration of the conference, which began in the Cabinet Room at Downing Street on 19 October. A large crowd cheered as the prime ministers arrived wearing silk hats and tails, each of their cars displaying their national flags.

Imperial conferences had lost none of their interest for the British press since the days of Laurier, Deakin, Botha, Seddon, Ward and Massey. Conjecture about arrival dates, details about the personal appearances of the prime ministers, and the size of the various delegations, had been swelling newspapers for weeks. When the Maharajah of Burdwan arrived in London with a retinue of 20 he made the New Zealand party look puny by comparison.55 Mackenzie King of Canada at 52, flush with an electoral victory after his spat with the Governor-General, Lord Byng, was welcomed as a leading statesman of academic distinction; Stanley Melbourne Bruce of Australia at 42, the youngest of the prime ministers, had also been re-elected a few days after Coates, and was a barrister and merchant, with a Military Cross won at Gallipoli. Wearing spats and limping from a war wound, he was described by the press as ‘a finely built “youth”’. The former Boer general, J. B. M. Hertzog, was 60, a judge, barrister and farmer. The press labelled him ‘the Pooh Bah of South African polities’. W. T. Cosgrave of Ireland was 46. He had survived a sentence of death after the uprisings of 1916, but was in poor health. The press knew little about W. S. Monroe of Newfoundland, who was relatively new to politics. At 45 years of age, the Maharajah was 6 feet 3 inches, and dubbed the ‘giant of the conference’. Coates, in the eyes of the press, ran him a close second. The Liverpool Evening Press called Coates ‘a magnificent figure — more than six feet tall, immensely broad and powerful; he looks a man in his early thirties rather than one of 48 years’.56

Prime Minister Coates in London, October 1926, speaking to Mrs Elliott-Lyn, the first English-woman to own and fly her own aeroplane. (Evening Post)

Nothing made the British warm more to their visitors than the declarations of loyalty that grew louder the nearer they all got to the seat of Empire. Before he left New Zealand Coates declared that he intended ‘to continue unaltered New Zealand’s traditional attitude towards Great Britain’.57 A few days later he declared that ‘we must keep New Zealand British’, adding that better trade relations would ensure that. ‘We owe a preference to British workmen against those not of our race,’ he declared.58 From New York Coates was quoted as saying: ‘We value the right of consultation in Empire affairs, but we recognise that it is not always practical to give actuality to the Dominions’ separate views. We gladly admit that final decision rests with the Imperial Government.’ Coates added, ‘a little wistfully’, that the Dominions far away sometimes ‘felt forgotten’, whereas Britain’s nearer neighbours seemed ‘more insistent and clamorous’.59 Hertzog was probably the person he had in mind when he made this comment. In the South African elections of 1924 Hertzog’s Nationalist Party had defeated the urbane internationalist, General Smuts; official pronouncements from Pretoria had taken on a more stridently parochial tone. Before leaving for the conference, Hertzog stated that he wanted ‘equal and absolute national freedom’ for the Dominions, each of whom he expected to have its own ambassadors, and to be able to sign treaties. Without this, the ‘Commonwealth of Nations must prove a fatal illusion’. The Irish Free State also wanted ties loosened with London, and after his own spat with the King’s representative in Ottawa, Mackenzie King of Canada was of a mind to accommodate them.60

The British Cabinet had been preparing for some months now and expected that the question of consultation between the Dominions and formal relationships with London would bulk large.61 They seem to have been surprised by the determination of the voluble Hertzog, who had brought a first draft of an intended declaration with him. Against the judgement of Coates, Bell and Bruce, a committee was established which eventually produced the famous Balfour Declaration, stating that the Dominions were ‘autonomous communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the Crown, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations’.62 Both Coates and Bell thought it was a ‘rotten formula’ that would weaken the ties of Empire, but they had little option but to go along with the declaration. Governors-General were soon telegraphed about their change of status; Fergusson noted disapprovingly in his diary on 21 November that in future he was to hold ‘exactly the same position as the King!!!, and to be no longer representative of H.M.’s Government’. That role would now be performed by a High Commissioner.63

The Governor-General, Sir Charles Fergusson, at Tongariro, May 1928.

The conference turned its attention to questions of trade and defence. Coates was no less enthusiastic than Massey and Ward before him for developing the Empire into a self-sufficient trading bloc with low tariffs between its members. The trouble was that free trade had long been a British article of faith. To give preference to the Dominions could only mean erecting barriers against everyone else, and since the Dominions specialised in producing only some of Britain’s needs, British governments shied at ‘Imperial Preference’. Elements within Baldwin’s Conservative Government favoured the idea, but progress at the 1926 conference, as at its predecessors, moved at a glacial pace. Coates made a strong case for closer trading ties, but conceded after the formal part of proceedings was completed on 23 November that the conference had produced no new developments. Like Massey before him, however, he kept reminding British audiences that New Zealand ‘offers you preference’ because ‘we prefer to buy British’. He asked them to reciprocate.64

On Imperial defence, however, Australia, New Zealand and Britain were swimming in the same direction. After the war Britain had been persuaded to construct a naval base at Singapore to defend its interests in the Far East and the Pacific. Progress on the base was slow, and for a time threatened by Ramsay MacDonald’s first Labour Government. By 1926, however, Stanley Baldwin’s Conservative Government was pushing ahead with the base and looking for a co-ordinated Imperial effort to provide the necessary services.65 Bruce and Coates strongly supported construction. Coates indicated before he left home that New Zealand would be prepared to pay more towards the base.66 In the end it was agreed that New Zealand would pay a total of £1 million over a decade, in annual instalments. New Zealand’s Parliament ultimately endorsed this in September 1927.67 New Zealand believed it had made a major contribution to its regional defence, and in 1928 paid the first instalment towards the dockyard, only to see progress slow in 1929 when MacDonald’s Government returned to office in London.

Coates was correct when he said that the conference had produced nothing materially new. But for 50 years now Imperial conferences had only in part been about what went on in formal sessions. The Dominions’ leaders always took the opportunity to fly flags around the British Isles, usually with trade promotion or financial investment in mind. There was a host of official receptions, dinner parties, freedom of the city presentations, visits to factories and awards of honorary degrees. Marjorie Coates was initially overwhelmed by it all,68 but came to enjoy the regular functions, the highlight of which was dinner at Buckingham Palace. There she met Queen Mary. The Queen had done her homework and surprised them with her knowledge of the Coates family. They also met Winston Churchill and his wife, whom Marjorie thought ‘the most beautiful woman I had ever seen in my life’.69

After visits to Liverpool, Sheffield (where they were given a canteen of cutlery), Belfast (where they were guests of Sir James Craig at Stormont Castle) and Dublin (where Coates was awarded an honorary degree by Trinity College) they went to Leominster to visit Coates’s family. There they spent time with Joseph Coates, a first cousin, who was an even larger physical specimen than Gordon.70 Then it was back to London where Marjorie spent Christmas with her relatives. Following a weekend at Chequers with the Baldwins and a quick trip to France to view war graves, they sailed for New York on 5 January and made their way to Washington, DC. Coates had a meeting with Secretary of State Frank Kellogg to discuss the South Pacific. They then made a brief call at the White House, where Marjorie found conversation difficult with ‘Silent Cal’ Coolidge. The Prime Minister was soon on his way to Montreal and Ottawa.71

King George V with his Prime Ministers at the Imperial Conference, 1926. Front: Stanley Baldwin (U.K.), W. L. Mackenzie King (Canada). Back: W. S. Monroe (Newfoundland), J. G. Coates, (N.Z.), S. M. Bruce (Australia), J. B. M. Hertzog (South Africa), W. T. Cosgrave (Ireland).

With his even taller cousins aboard the Aquitania, 1926.

Coates and Mackenzie King of Canada were not exactly soul-mates; the latter was as academically lettered as the former was unschooled. Yet King was a political survivor who held office as Prime Minister longer than any other person in the Commonwealth until Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore. Although King prayed a great deal, sang hymns and regularly received visions of his dead mother, he was a shrewd judge of people. In his diary he compared the visits of Bruce who stopped by in Ottawa on 3 January 1927 and then Coates ten days later. King found Bruce ‘a little bit inclined to lecture on [the] responsibility of Dominions’.72 After entertaining Coates and driving him about Ottawa, the Canadian Prime Minister was much more impressed. Coates ‘made a charming little speech’ at the Canadian Country Club, which was followed by a ‘few remarks in splendid fashion’ by Marjorie. Next day at the Château Laurier Coates again endeared himself to his host: ‘It was a simple sort of speech — not much to it — but a nice spirit and along lines devoid of question or reproach, a great contrast to Bruce … who has been most offensive and jingoist in some of his remarks & advice.’ So much was the contrast on his mind that King made the mistake of calling for three cheers for Mr Bruce, catching himself to his own mortification, and to the others’ amusement, halfway.73

Following trade talks King took the Coateses on a tour of the beautiful Gothic Parliament Buildings, which had been reconstructed after fire destroyed much of the complex in 1916. They saw a ‘wonderful flaming sunset effect in the corridor windows’. After dinner at Government House hosted by his nemesis, Lord Byng, King drove the Coateses through the cold to the station, whence they departed for Toronto. Their train-ride took them across Canada with a stop for one day in Winnipeg. Marjorie in particular enjoyed the trip through snow-covered country and was entranced by the icicles hanging from trees. Full of appreciation for the Canadian Prime Minister’s hospitality,74 they boarded the Makura in Vancouver, bound for Tahiti and Wellington.

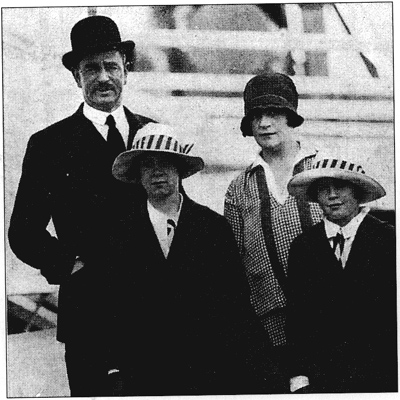

Arrival back, February 1927, with Sheila and Barbara.

Preparing them for the homeward leg of the journey was a letter from Downie Stewart. Things were running better at home, he said; butter and wool prices had firmed up. ‘Politically, I hear a good deal of growling from different parts of the country, but I cannot find much foundation for it, and no doubt a tour of New Zealand by yourself would soon tone things up again.’75 In fact it was another ‘tour’ that was beginning to occupy people’s minds. Back in September 1926 it had been announced that the Duke and Duchess of York were to visit New Zealand. Downie Stewart, Bollard and the Governor-General were busy planning itineraries. The Coateses stepped off the Makura in Wellington on 14 February, barely a week before the Royals arrived.