The Prime Minister hurried in from a Labour caucus meeting, arriving just as the doctors concluded that Coates was dead. ‘My God, what a tragedy! This man cannot be spared. Can’t you do something to help us?’ he beseeched them.1 On being assured there was not, his eyes filled with tears. He returned to the Government caucus room. Labour MPs immediately stood in silence, and passed a resolution of sympathy for Coates’s family before disbanding. News of Coates’s death spread around Parliament Buildings like wildfire. Rodney Coates seems to have heard news of Coates’s indisposition and telephoned Marjorie with the news that he had had some kind of seizure. A bulletin announcing his death was being broadcast over the radio just as Marjorie received a crackly trunk call from Wellington. Margaret Harding, who had so faithfully served him, heard the news over the radio. Iri recalls that Coates’s sisters, Ada and Dolly, arrived from Ruatuna. Dinner was served, with Ada cutting the meat, ‘all as if nothing had happened. Only Mum was excused. She sat by the fireplace looking a hundred years old. After a quick bite I was allowed to sit with her. Sheila had been visiting Chub [Barbara] in Whangarei and they arrived during the evening.’2 There was a feeling of shock as people tried to comprehend how someone, seemingly so fit and active, should suddenly die.

Steps were taken immediately to postpone the budget which Nash was to present that night. When the House assembled at 7.30 p.m. Fraser moved to adjourn proceedings until 2 June when ‘fitting references will be made to the life and work of this great statesman’. It is clear from his demeanour then, and over the next few days, that the Prime Minister had lost a true friend and confidant. Fraser’s tribute to Coates was both shrewd and remarkably fulsome, coming from someone of a different political persuasion. It is worth quoting in some detail:

By the death of Mr Coates New Zealand has lost a statesman of front rank. In Parliament, in Cabinet, as Prime Minister, in the councils of the British Commonwealth of Nations, and on the battlefield he proved himself to be of the truest steel — a trusted counsellor, a true friend and comrade, an intrepid leader, and a courageous and gallant soldier. He was deservedly popular among members of Parliament because he was always courteous and considerate, even in the midst of strong controversy. While in office and out … he always endeavoured to reconcile different and sometimes opposing points of view in the interests of the country’s unity and progress.

Whatever his party affiliations, Mr Coates was a progressive at heart — liberal-minded, a true Liberal in the widest sense of the word. This fact became more and more apparent as the years went on. He frequently expressed and acted on the most democratic sentiments in regard to the welfare of the people as a whole. He felt and manifested good will towards all sections of the community and, especially during the war years, when the war effort required frequent consultations, reconciliations and adjustments, he showed a well-informed and well-balanced appreciation of the position, difficulties and outlook of the wage-earner as well as of the farmer and business man. …

On all occasions he put his country first. Even the oldest political ties and party associations had to take second place when they clashed with his firm and fixed faith and principle of country, commonwealth and the common cause first.

As a member of the War Cabinet he was pre-eminent in certain phases of his work of which he had a special and intimate knowledge. His services were invaluable. To its all-important work he gave all of his best thought, his utmost energy, and his great experience of civil and military matters. He died as he lived, at his post — at work — in war harness.

His death is a great loss to New Zealand. It is a severe blow to the work of the War Cabinet and our war effort. …3

Those who genuinely mourned Coates were the members of the War Cabinet as well as his personal friends like Hamilton, Downie Stewart, Fred Waite, Bill Endean, Bert Kyle and Jack Massey; Holland issued a bland press statement which talked of Coates’s ‘lifetime of distinguished service not exceeded by any other man.…’ But he was just going through the motions. In reality, a thorn had been removed from his side, and there was no sign of grief.

In the Kaipara electorate, on the other hand, there was real ‘grief and desolation’ at Coates’s death.4 ‘A Mighty Totara Has Fallen’ was the headline in the North Auckland Times next day. Tributes flowed in from local authority leaders, the Northern Wairoa Returned Services’ Association, the Yugoslav community and local Maori, as well as from around the world.5 Marjorie, Sheila, Iri and Rodney quickly made their way to Auckland where they met up with Josie, and later, Pat, whom Fraser had accompanied to the train in Wellington so that she could go north to join her mother. Together they made their way to Wellington, arriving on the morning of Saturday 29 May as the first stages of the State funeral were about to begin. A requiem service was conducted by Archbishop West-Watson in the packed Cathedral Church of St Paul6 before Coates’s casket, draped with the New Zealand ensign and a Maori cloak, was transferred to the foyer of Parliament Buildings. There it lay on a bier surrounded with flowers. Members of the armed services, with which Coates had been associated for much of his life, were constantly in attendance. The four guards who came and went in relays consisted always of two soldiers (one Pakeha, one Maori), a sailor and an airman.

Next afternoon the casket was carried to a gun carriage outside Parliament by eight soldiers. They were flanked by Coates’s closest political associates, including Fraser, Hamilton, Nash, Forbes and Holland. The cortège moved by a circuitous route to the Wellington Railway Station. The band of the Trentham Military Camp played the ‘Dead March’; an escort of servicemen followed. Outside Defence Headquarters a big crowd had gathered. A military detachment with fixed bayonets and steel helmets presented arms in salute. Promptly at 4p.m. the train for Auckland, which Coates had boarded so many times at the very last minute, pulled out of Wellington. Marjorie and her daughters, Rodney and Tui Montague began the long pilgrimage to Auckland, stopping at many stations en route. Fraser, Nash and most of the rest of the ministry along with other parliamentarians, were also aboard.7

In Auckland the funeral took on a genuinely bicultural aspect. Elders from all Maori tribes had gathered at St Mary’s Cathedral in Parnell where they exchanged speeches with ministers. Princess Te Puea arrived, and was escorted into church by the MP for Southern Maori, E. T. Tirikatene. The Governor-General, Sir Cyril Newall, the British High Commissioner, Sir Harry Batterbee, with whom Coates had struck up a friendship, J. A. C. Allum, mayor of Auckland, judges, lawyers and military leaders, packed the elegant wooden building. Archdeacon E. M. Cowie, who had known Edward and Eleanor Coates, gave the address. A large crowd gathered outside the church, disrupting traffic.8

Coates’s casket is carried from Parliament, May 1943. Prime Minister Peter Fraser on the left, Adam Hamilton on the right, with Walter Nash, George Forbes and E. T. Tirikatene behind him. (Alexander Turnbull Library)

Funeral procession along Lambton Quay, May 1943. (Alexander Turnbull Library)

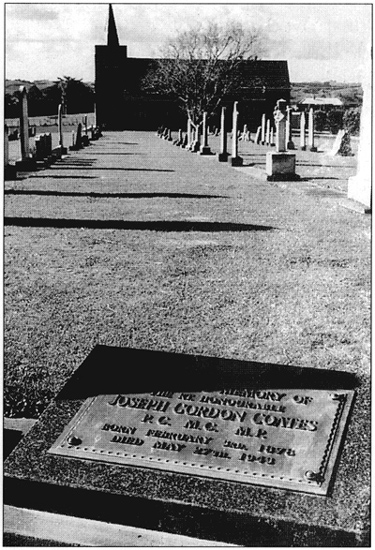

The casket lay overnight under military guard in the station-master’s private room from where it was conveyed by hearse to the junction of Matakohe and Ararua roads on the morning of Tuesday 1 June. There it was transferred to a gun carriage. Once more ministerial colleagues accompanied the procession as it wound its way up the hill, this time with the band of the Royal New Zealand Air Force playing the ‘Dead March’. Unable to walk far, Marjorie Coates watched from the top of the hill. On the sunny knoll overlooking the township and a wide arm of the Kaipara Harbour, where a crowd of nearly 5,000 friends and constituents had gathered, the arrival of Coates’s casket was greeted with shrill Maori wails and green ponga fronds shimmering in the air. A male Maori choir sang a Maori hymn, and then the vicar of Paparoa, the Rev. M. L. A. Bull, conducted the committal service. The crowd sang ‘Abide with Me’ and the choir sang the ‘Nunc Dimittis’. The casket was lowered into the grave beside a typically dishevelled Northland cabbage tree and a totara, and next to Coates’s mother and father. A firing party discharged three volleys over the grave; these were interspersed with wails from local Maori. A bugler played the ‘Last Post’; the escort then presented arms in a final salute. ‘Reveille’ sounded out, following which Marjorie, her daughters, Rodney, Ada and Dolly Coates filed past the open grave, followed by the Prime Minister and the many dignitaries present. Gordon Coates was at rest in a spot that he had known well, lying about four miles by road from Ruatuna, but much closer by the track which he rode so frequently as a boy.9

The official party, including Princess Te Puea, family and friends, were invited back to Coates’s home for afternoon tea. Many noted that Fraser was genuinely upset, tears streaming down his face. After recovering his composure, he was anxious to be of assistance to the family.10 The Prime Minister assured Rodney of the Government’s support should he wish to contest the by-election for Kaipara. Rodney’s health was not good. He declined Fraser’s invitation, much to the chagrin of his sister Ada, who would have much liked the invitation herself. However, the tall, able horsewoman, renowned for her abrupt style, was never asked. She became openly hostile to some of Coates’s supporters when they proceeded to select a Dargaville lawyer, Clifton Webb, instead.11

Meantime newspaper editors, clergymen, colleagues and friends had been wrestling to come to terms with the meaning of the life so suddenly snuffed out. Since Coates’s death had been unexpected, few had had time to collect their thoughts. Yet, there is a remarkable consensus in their columns on the main features of Coates and his historical significance. Nearly every newspaper and commentator drew attention to Coates’s physique and energy. The words Vigorous’, Virile’ and ‘strenuous’, used by the Dominion, were repeated in many other places, and drew attention to the essentially male characteristics of the man and the influence these had on his followers.12 The New Plymouth Daily News spoke of his ‘arresting figure’, which the Nelson Evening Mail and the Otago Daily Times linked to his manners, speaking of his ‘vigorous and picturesque personality’, and his ‘gallant’, ‘courteous’ and ‘debonair’ style. One called him a ‘happy warrior’.13 Others spoke of his ‘urbane’, ‘cordial’, and ‘honourable’ characteristics. The Hawkes Bay Herald Tribune called him ‘nature’s gentleman’, a view that some others who noted his frankness, his occasional brusqueness, and even his slightly autocratic tendencies, would probably have disputed. Nothing disguises the fact, however, that Coates was what was often called a ‘man’s man’.14 There were no shades of grey in any of the descriptions.

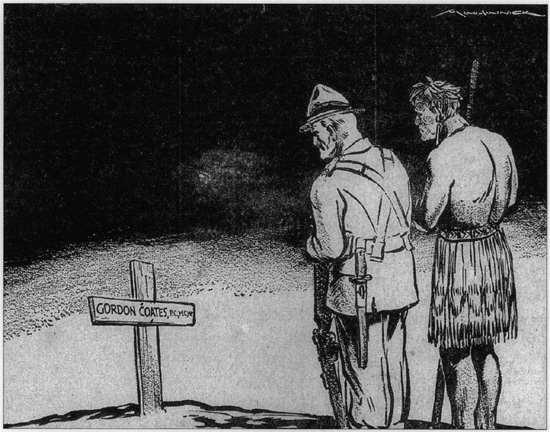

Minhinnick, ‘Died on Active Service.’ (New Zealand Herald, 28 May 1943)

When it came to his political thought and style there was agreement that Coates was ‘liberal in outlook’, possessed ‘wide vision’, was ‘forthright’, ‘courageous’, ‘tireless’, ‘fearless’ and ‘determined’.15 No one labelled him an intellectual; indeed, some drew attention to his modest educational achievements. But most commentators noted his quick comprehension — what the Taranaki Herald called his ‘keen intelligence’.16 Opinion varied about the legacy Coates left. The Northern Advocate felt he had done more than any politician to put Northland on the political map, a judgement that was certainly true.17 Others thought his legislation establishing the system of main highways and his relentless pursuit of electric power generation in the 1920s to be his enduring monuments.18 Everyone praised the way in which he had put party considerations aside in the national interest during the last three years of his life.

Coates’s parliamentary colleagues reassembled on the afternoon of 2 June to remember him. Again the same adjectives flowed, backed by occasional anecdotes. Once more Fraser spoke movingly, and quoted from Sir Walter Scott’s ‘Coronach’:

He is gone on the mountain,

He is lost to the forest,

Like a summer-dried fountain

When our need was the sorest.

Hamilton called Coates a loyal colleague and a treasured friend. He mentioned his ‘utter indifference to personal criticism’ which sometimes caused him to be misunderstood, and to become ‘easy prey to the scandal monger’. Yet his life, in Hamilton’s view, was an open book’.

Apart from Hamilton, it was the Labour MPs who spoke with most feeling. Although some of them had been in Parliament for many years with Coates, they had only come to know him intimately since he joined the War Cabinet. Nash, whom Coates had misguidedly at one point likened to Stalin, clearly enjoyed getting to know Coates during the war. He recalled Hamilton saying to him at the time the War Cabinet had been formed: It will be alright. You need not worry [about Coates]. You will wonder at times, just what he is going to do, but he will never let you down. He will never fail you.’ Nash added that when Fraser had been overseas in 1941 and he was left holding the fort, ‘no man could have been more helpful [than Coates], more faithful, more loyal, more complete in his devotion to what I wanted done.…’19 Nash was pointing to that characteristic of Coates’s — to offer complete loyalty to someone in authority, something he had learned in France in 1917–18, and which Forbes took advantage of during the Depression.

Perhaps the most perceptive comment about the significance of Coates’s life came from the editor of the small Kaikohe weekly, Northern News. Having had the benefit of several days to reflect, he wrote:

Now and then, in a world that seems increasingly breeding men lacking both in colour and character, there arise men who seem incarnations of the spirit and temper of the people among which they were born and bred, typical embodiments of their national characteristics. Such a man was Abraham Lincoln, of the America of a century ago; such in a great measure was Joseph Gordon Coates of present-day New Zealand, a nation in the making. A son of the soil, brought up largely amid pioneer conditions, his was essentially the pioneer character: self-reliant, intensely practical, facing difficulties with cheerfulness and courage as enemies to be vanquished, instinctively judging men by what they are and not what they seem to be. Such conditions breed strong forceful characters, impatient of conventions that would restrain their energies, seeing only the job to be done and the most direct means of doing it. A tendency perhaps to over-estimate the need for frank speaking and to under-estimate those little social graces and hypocrisies that do much to smooth the rugged edges of social intercourse. Every man has the defects of his good qualities. …

Mr Coates was not, and never professed to be, a great statesman, but he had some statesman-like qualities and he served his generation energetically and honestly according to his lights and his ability. Higher praise no man can have.20

The sage of Kaikohe had struck the right note. Apart from Sir Francis Bell’s few days in office, Coates was the first New Zealand born Prime Minister. He was a genuine product of the Antipodes. Brought up according to British traditions, he was nevertheless, like many early colonials, less formal in manner and speech, and less structured ideologically than his forebears. In a crisis Coates was capable of considerable creativity. He lacked the boldness of a Savage, Fraser or Nash; social experimentation was not second nature to him. Yet he helped move New Zealand’s conservatives towards State intervention. He was clearly and unequivocally a transitional figure in New Zealand politics between the earlier, simpler world of Seddon and Ward, and the later regulated, controlled environment of Fraser, Nash, Norman Kirk and Robert Muldoon.

Coates’s affairs took a long time to sort out, largely because his mother’s estate had still not been disentangled. Coates’s Wellington friend, Jack Stevenson, was believed to hold a will signed before Coates had gone to Ottawa in 1932 but was unable to find it. Coates — perhaps with some premonition — had asked Josie to type up a will for him not long before his death, but she had not yet done so. As a result, the only extant document was the will Coates had left in October 1916 before he went to the war.21 Written at a time when he was newly married with only one daughter, and was still anticipating sons, it was hopelessly out of date. Basically the will divided Coates’s estate between Marjorie and family on the one hand, and Rodney.

Montague was soon assigned to William Perry who was appointed to fill Coates’s place in the War Cabinet. Fraser asked her, however, to help sort out Coates’s affairs, which she did, sometimes stepping on Marjories sensitivities in the process. Montague destroyed many of Coates’s papers that she believed irrelevant, and made the rest available to O. S. (Budge) Hintz of the New Zealand Herald; he had signified an interest in writing a biography but seems to have been easily waylaid by his naval duties. Montague gathered in Coates’s debts, his accounts at the Wellington Club, his Bellamy’s bills and his dry-cleaning accounts, while Oliver Nicholson worked in tandem with Jack Stevenson. They commissioned valuations on the farm, part of which belonged to Coates. The early months of 1943 had been especially dry and the farm was carrying debts for cattle feed. Moreover, stock prices were down. When all the mortgages were allowed for, Coates’s share was estimated at a net loss. Stevenson passed on this news to Fraser. Cabinet decided on an ex gratia payment of £1,250 to Marjorie, who was very short of money.22 Fraser offered further to assist Rodney, who was one of the executors of Coates’s estate, with an approach to the Inland Revenue Department about back taxes owing from the farm. However, it took time for Rodney to gather up the relevant material. In July 1945, he suddenly died of a heart attack in a Wellington hotel on the night before an appointment with the Prime Minister.

This turn of events further complicated matters. It was not until 1948 that Coates’s estate was eventually finalised. Des Coates, Rodney’s only son, and the executor of his estate, decided to renounce any share in his uncle Gordon’s. Ada Coates, who lived until 1976, bought the Ruatuna homestead block of 252 acres with the aid of her widowed sister Eva Aickin, and in due course it passed to Joy Aickin who has continued to farm pedigree cattle to this day. Des Coates farmed 800 acres from Rodney’s share of the Unuwhao Block. The rest was divided into five farms which were sold to returned servicemen.23 Marjorie and her daughters were able to receive payments from that share standing in the name of Gordon Coates.

Meantime, the daughters had all gone their various ways. Sheila remained in the north with her family and Barbara (Chub) worked in Auckland, where she developed a lifelong passion for bowls. Pat was employed in Auckland for a time by the Security Intelligence office. She met Ben McCulloch, who was an American serviceman in Auckland, and married him in May 1944 before going to live in California. Iri had joined the Department of External Affairs and was posted to the United Nations in New York in 1946. Sir Carl Berendsen hosted her wedding to an American, Lincoln Bloomfield, in the New Zealand Embassy in Washington DC in July 1948. Josie worked for the US Signal Corps in Auckland. In November 1946 she took Marjorie, who by now found walking difficult, to see Pat and her first child. In Washington DC Josie was offered a job at the Australian Embassy, met an American, and was married in 1949. Once more Sir Carl hosted the function at the New Zealand Embassy. All three daughters have lived and raised families in the United States. Marjorie returned to New Zealand and lived first with Sheila and her family in Walton Street, Whangarei, and then with Barbara (Chub) at Arcadia Road, Epsom. Marjorie died in 1973, Barbara in 1994.

Coates’s Memorial Church, May 1950.

Coates’s reputation lived on after his death. In 1944 a group of ‘anonymous well-wishers’, who in reality were Sir Ernest Davis, Oliver Nicholson and Noel Cole, decided to erect a memorial to Coates at the Dargaville turn-off to the main northern highway. This was the point where Coates, whenever driving north, had announced to whoever was with him: ‘Well, I’m home again.’ After much debate about the wording to be placed on the plinth it was unveiled on 28 July 1944 and read:

To the memory of the Rt Hon Joseph Gordon Coates PC, MC and Bar, MP (1878–1943) Prime Minister of New Zealand 1925–28. Member of Parliament for this district from 1911 until his death. Farmer, soldier, statesman. He was indeed a Man.

There followed a Maori inscription which, translated, means ‘Rest thou, O father, upon the great work you have performed for Pakeha and Maori alike’. A smaller inscription below records that ‘18 miles west of this corner at Matakohe, Joseph Gordon Coates was born and had his home, and there in the churchyard he lies at rest’. The granite for the plinth originated in the Channel Islands and came from a pier of the Waterloo Bridge in London.24

Peter Fraser remained faithful to Coates’s memory long after he had been relegated to part of the National Party’s history. Immediately after Coates’s death, Fraser suggested to Rodney Coates that the burial should be on Auckland’s North Shore. ‘We have Savage on the other side and the two memorials would be the gateway to the North,’ he said. When Coates’s family preferred to bury Gordon Coates at Matakohe, Fraser instructed the Department of Internal Affairs to maintain an interest in the upkeep of Matakohe cemetery. Ada Coates persuaded the Government to contribute to a memorial church, and plans were completed in 1945 by Horace Massey of Auckland.25 By the time construction was finished in 1950, Holland was Prime Minister. Fraser’s heart was now giving him trouble, but he went north with Holland for the official opening of the church on 27 May 1950, the seventh anniversary of Coates’s death. It was a reunion of many of Coates’s surviving friends and supporters. Official cars ferried family and former colleagues to Matakohe, including Adam Hamilton, Carey Carrington, Sir Alexander Young, Tom Seddon, and Tui Montague (now Massey). Margaret Harding was there; Princess Te Puea was unable to attend, but sent a message of regret, noting that Coates had been ‘a faithful friend of mine’.26 It was a sentiment shared that day by all present.