CHAPTER II

THE COLLISION

A CROWDED HARBOUR

WEDNESDAY, 5 DECEMBER 1917, HALIFAX HARBOUR WAS crowded with marine activity. The British ship Middleham Castle had just been replaced in dry dock by the Norwegian ship Hovland. Another British ship, Picton, was being unloaded so she could enter dry dock when repairs to Hovland were finished. Picton had been towed to Halifax with a damaged rudder. Nearby, two other British ships, Curaca and Calonne, were loading horses for shipment overseas. Farther along were Canada’s two submarines, CC1 and CC2, recently arrived from the Royal Canadian Navy’s west-coast base at Esquimalt, B.C., after an arduous trip of nearly four months through the Panama Canal. Still closer to the harbour entrance, under command of Lieutenant Donald F. Angus, were Alfreda, Armstrong, Beryl, Liberty, and Lighter, the five boats operated by the Canadian Army Service Corps that ferried troops and supplies to the islands in the harbour. Tied up across from Halifax at Dartmouth were the US Navy ship Old Colony and a US Coast Guard cutter, Morrill. Old Colony was in fact a passenger ship that the navy had taken up and agreed to transfer to the British. She was en route to England, and put into Halifax for repairs because her officers were worried she was unprepared for a winter journey across the North Atlantic.

The schooner St. Bernard was at the wharf by the Acadia Sugar Refinery, beside a Canadian ship with the unlikely name of Ragus (sugar spelled backwards). Kanawha was at the Furness-Withy wharf and Max C., a former sailing vessel, at the N.M. Smith wharf. Also in harbour was the steamer North Wave. Anchored down harbour closer to the sea were a British light cruiser, Highflyer, and an armed merchantman, Knight Templar. Another armed merchantman, Changuinola, would arrive outside Halifax that evening. Those ships were to escort the convoys scheduled to sail in the next few days, and they were substantial ocean-going vessels. Highflyer was 113 metres in length, displaced some 5000 tonnes, and had a crew of 450. Knight Templar, a converted passenger liner, and Changuinola, a converted fast cargo vessel, were larger still, though with smaller crews (about 220 in the case of Changuinola), as they did not carry the full armament and equipment of a purpose-built warship.

These British and US ships dwarfed the small patrol vessels of the Royal Canadian Navy.2 The largest, such as the Acadia, and Margaret and Cartier (both tied up at the dockyard, near the berth of the permanently moored HMCS Niobe), Canada and Hochelaga (anchored off the shore), displaced from 700 to 1000 tonnes, were a little under sixty metres in length and operated by crews of fifty to seventy officers and seamen. Smaller still were the first group of steel anti-submarine trawlers that had recently arrived from the shipyards, about thirty-nine metres in length and displacing about 300 tonnes. According to historian John Griffith Armstrong, there were at least fourteen of the new wooden anti-submarine drifters present at various places in the harbour, also newly arrived from the shipyards. These craft were only eighteen metres in length and each carried a crew of eleven.

Also in port was the convoy liaison tug, Hilford, as well the tugs Nereid, Roebling, Douglas H. Thomas, Booton, Maggie, Musquash, Gopher, Lily, Stella Maris, and Wasper B. Musquash and Gopher had been commissioned in the Canadian navy and fitted with minesweeping gear. These, together with seven trawlers purchased in the United States and commissioned under the uninspiring names P.V. I through P.V. VII (“P.V.” presumably stood for “patrol vessel”), operated in pairs, towing a cutting wire between them. They swept the harbour approaches every morning to guard against mines that might have been laid under cover of darkness by disguised German ships. The cutting wire was designed to break the mooring lines of contact mines, which were anchored to float beneath the surface and explode against the vulnerable lower hull of any passing ships that touched them.

Crossing back and forth across the harbour were the two ferries, Dartmouth II and Halifax II. A third ferry was being repaired. Today, two bridges join Halifax and Dartmouth. In 1917, the shortest way from Halifax to Dartmouth was to cross the harbour by ferry.

After narrowing as it passes between Halifax and Dartmouth, Halifax harbour widens into the large anchorage known as Bedford Basin. At the entrance to the Basin, HMCS Acadia was on station under the control of the Royal Navy inspection staff as a guard ship to ensure that none of the ships on passage to or from neutral ports departed before they had been examined and cleared. Although harbour records could not be found, Lloyd’s records of shipping movements, and the incomplete records for merchant shipping that survive in Canadian naval records, suggest that on 5 December 1917 there were perhaps fifty merchant ships in Bedford Basin, possibly more. Many were British, but there were also ships from other Allied and neutral nations. About twenty-seven of the vessels, carrying cargoes to British and French ports, had come for the slow convoy scheduled to sail on 7 December. Many of the rest would have been ships sailing to or arriving from neutral ports, including several on the Belgian Relief service, for inspection by the Royal Navy examination unit. Among the latter was the Norwegian ship IMO.

FIGURE 2.1 | Norwegian SS IMO, from stern, well before the explosion. Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, M2013.28.1 IMO/Kristiania. Samuel H. Prince Collection.

She had crossed the Atlantic in ballast (empty) on her way to New York to pick up a cargo of relief supplies when she put into Halifax, as required by the British Admiralty, to be checked to make sure she was not carrying any contraband (i.e., anything that might be useful to the enemy). Having been cleared for departure by the Royal Navy contraband control staff, her captain was impatient to leave. By the time she was coaled, however, the anti-submarine nets were closed for the night.

MORE THAN A HARBOUR

In 1917, Halifax was more than just an important harbour. It was the provincial capital and the city where Nova Scotians went to get an education or seek medical help. It was the home of Dalhousie University, St. Mary’s College, the Academy of Mount St. Vincent, the Royal Naval College of Canada, the School for the Deaf and Dumb, and the School for the Blind. It was the home of the provincial hospital, Victoria General, as well as of the provincial mental and tuberculosis hospitals. It was the main treatment centre for venereal disease. It was the commercial centre of the province and the region. Although there are no records for the week of the explosion, hotel records from the previous week show that of the 110 guests registered at the Halifax, King Edward, and Queen hotels, half were from Nova Scotia and neighbouring New Brunswick. There were eighteen from Ontario, most from Toronto, and twelve from Quebec, all from Montreal. There were ten from the United States and five from the United Kingdom.

Halifax was also the place where many Nova Scotians did their military service in the fortress garrison, and the navy’s dockyard, harbour craft, and patrol vessels. On 5 December, there were soldiers and sailors in Halifax from Advocate Harbour and Amherst, Bear River and Bridgetown, Conns Mills and Denmark, Ellershouse and Hantsport, Hubbards and Glace Bay, Little River and Mahone Bay, Parrsboro and Reserve Mines, Springhill, Tatamagouche, Westville, Woods Harbour and Yarmouth, and seventy other Nova Scotia communities. Everyone in Nova Scotia knew someone in Halifax. For all that, Halifax was still a small community. Its population was 55,000.

There was something else about Halifax in December 1917 that, in retrospect, seems almost unbelievable. Despite the city’s vast experience with war and the current war-related activities, despite the continual visits from ships carrying munitions, and despite the widespread belief that German Zeppelins could cross the Atlantic and bomb the city, Halifax had no emergency plan. The submarine nets and the guard ships at the harbour entrance were to prevent enemy ships or submarines from entering. There was nothing similar to protect the civilian population, though there were strict rules about blackouts to make certain that arriving ships did not show up against the glow of the city: “At night … we practically lived in darkness. Shades had to be drawn and openings covered to keep any particle of light from showing. Being a garrison city … we were ever fearful of bombardment from German battleships. There were constant reports of German U-boats lurking outside the harbor.”

Yet if something did happen, the city authorities and the military had no plans to warn the city’s residents. The need for such a warning had never occurred to them.

There was another problem. The city’s fire protection was—in the opinion of the insurance industry—far less than adequate. The Nova Scotia Board of Fire Underwriters was so concerned about that, and the fact that most homes were of wooden construction, that it asked the US National Bureau of Fire Underwriters to review the situation in Halifax. Its report found the Halifax fire department “weak in trained men,” the city’s water supply “barely adequate” and “somewhat unreliable,” and the city’s fire alarm system “unreliable and inadequate.” It said residential areas like the North End were “mainly frame with shingle roofs and, although most of the dwellings are detached, some are in frame rows and there is the liability of extensive fires because of the shingle roofs.” The bureau reported that Peter Broderick, Halifax’s sixty-year-old fire chief, “makes occasional inspections for dangerous conditions but these are of little value and records of inspections are not kept.” (Broderick died in 1916 shortly after the report was written, but his son who was also a firefighter lived long enough to become one of the first persons killed in the 1917 explosion.)

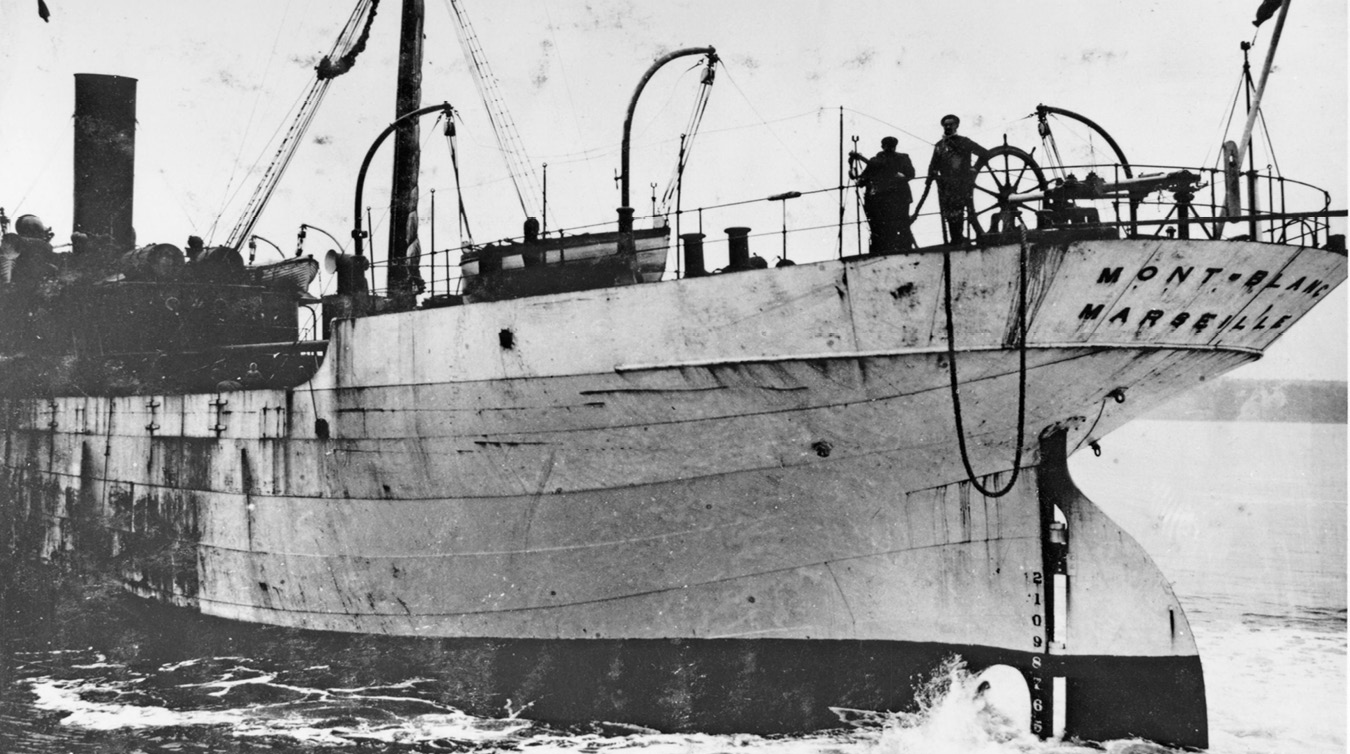

MONT-BLANC ARRIVES

The most important event in the build-up to the 1917 explosion was the arrival at Halifax of the French steamship Mont-Blanc carrying a deadly cargo of explosives, the cargo that would explode on 6 December.

The chain of events that led to the explosion involved three other vessels and a number of decisions, and failures to make decisions, that taken together make a set of coincidences that rival the story of Titanic’s meeting with an iceberg.

The smallest vessel involved was the tug Stella Maris. Every day, she made regular runs from the dockyards deep in the harbour along the Halifax shore to Bedford Basin, towing scows carrying ashes so she could dump them in the deep waters of the basin. At night, she tied up. She was at work early on the morning of Thursday, 6 December, and her presence affected what happened.

FIGURE 2.2 | French SS Mont-Blanc, from stern, well before the explosion. Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, MP18.196.11.

The second player was an American steamer, Clara. What little is known about her is from the message sent by the British convoy officer in New York to Halifax on 3 December stating that she and Mont-Blanc were both on their way to join the slow convoy due to sail from Halifax on 7 December. Clara was a bigger ship than Mont-Blanc, and carrying a cargo of steel and oil to La Rochelle, France.3 She had departed from New York on 1 December, a day earlier than Mont-Blanc. Clara must have arrived, like Mont-Blanc, on the late afternoon or evening of 5 December, when the anti-submarine nets were closed, as she was waiting in the examination anchorage on the morning of 6 December. Clara proceeded into port before Mont-Blanc and was well into Bedford Basin before the collision that led to the explosion. Nevertheless, Clara was a key factor in what happened. In fact, her pilot, Edward Renner, was criticized at the subsequent inquiry for the way he directed her that morning. By the time of the inquiry Clara had sailed with the slow convoy, whose departure had been delayed to 11 December by the disaster. Renner did not remember her name, and the inquiry appears to have made no effort to discover it, let alone obtain a statement from the ship’s captain.

The first of the two major players was SS IMO, the Norwegian ship that had been delayed from sailing Wednesday evening because of the late arrival of coal. On her departure from Bedford Basin on Thursday morning, she collided with the incoming Mont-Blanc, the main protagonist in the disaster. The crews of both ships were long-serving seafarers; as such, they were unlikely participants in a catastrophe.

TWO EXPERIENCED SHIPS

At forty-seven years of age, IMO’s captain, Haakon From, had spent more than a quarter of a century at sea, twelve years as captain. He had been to the Antarctic both on IMO and on his previous ship, Fulwood. His crew was equally experienced. The second engineer, Anton Andersen, was sixty-one—he had spent nearly half a century at sea. Even younger ship’s crew like Louis Skarre and Sigrid Sorensen, both twenty-nine, had been at sea for a decade. Many—including Andersen, Skarre, Sorensen, and From himself—were from a Norwegian fishing town called Sandefjord. The others were from Sandefjord’s neighbours, Tonsberg and Larvik, and another smaller town, Huvik. These towns had bred several generations of world-class seamen, for they were the homes of the Norwegian whale fleet, and Norwegians were the world’s most experienced whalers. While the bulk of IMO’s crew was Norwegian, there was one Frenchman, Joseph Trepanier. Although IMO was in Halifax while in transit to New York to pick up relief supplies, she was normally a whaling supply ship. Originally built as a passenger ship, Runic of the British White Star Line, she was a substantial vessel of about 5000 gross tons, and 131 metres in length. She was thus considerably larger than Mont-Blanc, 3121 gross tons and 100 metres in length.

Because the French keep detailed handwritten records—records that can still be found at the Marine museum in Paris—a great deal is also known about Mont-Blanc. Her captain, Aimé Le Médec, had been a captain for only a year and this was his first voyage with Mont-Blanc. He had joined her in Bordeaux as she left for New York. However, Le Médec had been with the Compagnie Generale Transatlantique (the French line) since 1906, when he already had eleven years at sea. He also came from a seagoing family. Born in the Loire Valley, Le Médec was the son of a sea cook and he grew up in the seaport of St. Nazaire, as did his second-in-command, Jean Glotin, and the chief engineer, Antoine Le Gat.

Like the crew of IMO, the crew of Mont-Blanc crew came largely from seaport towns. The two second lieutenants, Pierre Hus and Joseph-Eugène Levesque, were from Saint-Malo, home port of the French explorer Jacques Cartier. Five sailors were from Mont-Blanc’s home port of Bordeaux; others were from St. Nazaire, Saint-Malo, Nice, Rochefort, Noirmoutier, and Lorient—all towns along the French coast. The men in charge of the engine room were mainly French, but the oilers were Algerian—Cisse Bonna, Doye Assane, and Sissoko Toumani, all from Dakar. The ship’s steward, Theodore Duvicq, was also Algerian. When Mont-Blanc took on two new crew in New York, one, Marcel Colon, was French, but the other, Emile Colson, was American. He replaced Mathieu Chastanier as ship’s baker, an unusual job for a foreign national on a French ship.

Neither From nor Le Médec was left to his own resources in Halifax harbour. IMO’s pilot was William Hayes, who at fifty-six was the most senior pilot in Halifax. Mont-Blanc’s pilot was Francis Mackey, forty-three years old with nineteen years of experience as a pilot. He was the only pilot in the harbour with a master’s ticket. Neither Hayes nor Mackey had ever had an accident. Moreover, the weather was not a factor in what happened. Thursday, 6 December 1917 was a clear day with only a light wind.

In contrast to IMO’s humanitarian mission, Mont-Blanc transported war supplies under the direction of the French government. The ship had come from Bordeaux to New York, where she had been crammed full of deadly explosives. According to a copy of the manifest sent to the Governor General of Canada, her forward hold contained 2330.9 tons of barrels of wet and dry picric acid, the most common filling for high-explosive artillery shells used by the Allies in the First World War. Aft, she carried two other types of high explosives: 161.5 tons of gun cotton and 225 tons of trinitrotoluene, better known by the abbreviation TNT. On Mont-Blanc’s deck, tied down with ropes, were iron drums containing 244.3 tons of monochlorobenzol. The latter, whose uses included the production of picric acid, was more stable than benzol, the hydrocarbon fuel from which it was derived. The use of the short form “benzol” on the ship’s bill of lading led the officials who conducted the inquiry into the accident and subsequent authors to believe that the highly volatile fuel had in fact been on deck, a violation of safety precautions. That was not the case, as an explosives expert who testified late in the inquiry suggested, and he was proved right as further documentation came to light. Monochlorobenzol, like TNT and gun cotton, was less flammable than the picric acid that formed the bulk of the cargo. Nevertheless, Mont-Blanc was a floating bomb.4

MONT-BLANC’S TRIP TO HALIFAX

After taking on her cargo, Mont-Blanc had steamed up the Atlantic Coast on her own. The British officer in New York said she was too slow for an American convoy: Perhaps the Canadians would let her join a slow convoy in Halifax? Mont-Blanc certainly was slow. At 3121 gross tons, 100 metres long, and 12 metres wide, her heavy and unwieldy cargo left her with a maximum speed of 7.5 knots—about 14 kilometres per hour—and probably less. To defend herself, she had two guns, one fore and one aft, adding to the appearance of sloppiness and the fact of overcrowding. There were piles of shells beside each gun (stacked around the barrels of monochlorobenzol) and six soldiers—Emile Arnoux, Louis Gueguenou (a last-minute replacement), Camille Ligonnière, François Montmayeur, Leopold Raymond, and Yves Gueguiner—who squeezed in with the crew to staff the guns in case of attack.

Shipping a dangerous cargo in a ship so slow and ill protected may have seemed foolhardy, but it reflects the Allies’ position in the fourth year of war. In November 1917, the month before the explosion, forty-seven large Allied ships and twenty-three small ones were sunk by enemy action. The week Mont-Blanc sailed to Halifax, German submarines sank seventeen more Allied merchantmen, all more than 1600 tons. Those losses forced companies, such as the French line, to purchase second-class ships like Mont-Blanc—she was acquired on 28 December 1915—and to load them with deadly cargo.

Mont-Blanc arrived outside Halifax shortly before sunset and was immediately joined by her pilot, Francis Mackey, who had just brought out another ship. Mackey’s presence made Mont-Blanc’s captain confident that his ship could enter harbour immediately. The examining officer, Mate Terrence Freeman, Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve, checked Mont-Blanc’s papers and found everything in order, but he told Le Médec the gates of the anti-submarine net were closed for the night. Le Médec and his crew would have to resign themselves to another night at sea. Mackey remained on board. After clearing Mont-Blanc for entry, Freeman wired his superiors news of her arrival: “5:25 p.m. Anchored in X.A. [Examination Anchorage] till morning French steamer ‘Mont Blanc’ from New York to Bordeaux, France, with cargo of explosives for French government. Crew allied and neutral.”

While Mont-Blanc was in New York, they had watched uneasily as wooden panels were installed in the holds, and more uneasily when they saw workmen using copper nails to prevent sparks and wearing only canvas or rubber-soled shoes. They had rigidly followed the resulting no-smoking policy, especially when barrels of monochlorobenzol were lashed down on deck. They were relieved to have survived their lonely trip from New York to Halifax. For the rest of their journey, they would be part of a convoy.

THURSDAY MORNING

On Thursday morning, the morning of the explosion, the first ship in the examination anchorage to get under way was the armed merchant cruiser HMS Changuinola. Once the submarine nets were raised, she moved quickly into the harbour and dropped anchor near Highflyer. She was not involved in the events that followed. Next to enter was Clara. Her pilot, Edward Renner, kept her moving swiftly along because, until Clara approached Bedford Basin, there was little other traffic except the two ferries shuttling back and forth between Halifax and Dartmouth. Trailing along well behind Clara was the slower Mont-Blanc. As she entered the harbour, her crew looked around with relief. They were safe for a while. Her first mate asked the captain if he should raise the red flag showing Mont-Blanc carried munitions. Le Médec said no. It was against the rules—the British were afraid spies would be able to report the movements of munitions ships, identifying them as priority targets for Germany’s submarines and surface raiders.

While Changuinola, Clara, and Mont-Blanc were entering harbour, IMO was getting under way in Bedford Basin, the innermost part of the harbour. Her pilot, William Hayes, had gone home overnight, but was back at first light. At his signal, IMO raised her anchor and circled around the other ships at anchor. Because she had been cleared the day before, she did not notify anyone she was leaving. She simply began her journey out of Bedford Basin and into the Narrows en route to the open sea. Because of Norway’s neutrality, IMO had crossed the Atlantic alone and intended to continue on her own to New York. Her crew had painted her with a big red cross and had hung a banner with the words “BELGIUM RELIEF,” a practice with many of the humanitarian vessels in order to alert German submarines of their protected status.

RIGHT OF WAY

The rules in Halifax, as in other harbours, called for ships to keep to starboard (to the right), and to pass each other port to port (left to left). That meant Mont-Blanc should have been entering the channel on the starboard or Dartmouth side of the channel, and IMO should have been exiting along the opposite, Halifax shore. The ships would have been well separated, even in the Narrows. Mont-Blanc did—until the last moment—stay on her proper course, but IMO left harbour on the port side of her channel—the Dartmouth side, and the same side as the incoming Mont-Blanc. There was a reason for IMO’s course, and it is understandable that she was where she was. Nevertheless, her position on the wrong side of the channel was the first major development in a chain of events that would lead to the collision and the subsequent explosion.

As IMO cleared Bedford Basin, she prepared to cross over to the Halifax shore and signalled her intention to do so with a single short whistle blast that meant she was altering course to starboard. However, the incoming Clara had already moved across to the Halifax shore and replied to IMO with two short whistle blasts, which meant she was keeping to port—that is, on the Halifax side. There was lots of room and no reason why the two ships had to change channels. The ships remained on their courses and passed starboard to starboard without incident. Because of the narrowness of the channel, Clara’s pilot, Renner, was able to use a megaphone to call to IMO and tell her that another ship was coming up behind him. That, of course, was Mont-Blanc.

The rule about keeping to starboard is a convention, just as are the rules about keeping to one side of a highway. On a highway, however, it doesn’t matter whether all vehicles keep to the right or all vehicles keep to the left, as long as all do one or the other. Things are different on water. Though it was usual for ships to pass port to port, it was all right for them to pass starboard to starboard providing both agreed. Since very few ships had radios in those days, ships meeting each other indicated their intentions by whistling. One whistle meant a turn to starboard. Two meant a turn to port. Three meant stop or going astern.

Once Clara passed, IMO again prepared to cross to the Halifax or starboard side of the channel. However, she then saw Stella Maris come out of the Halifax dockyards. Because Stella Maris was slow and somewhat ungainly with her scows in tow astern, IMO decided to remain on the port side of the channel until she had passed her. She whistled twice to show she intended to stay to port, leaving the Halifax shore clear for Stella Maris. It is not clear from testimony at the later inquiry whether Stella Maris accepted that decision by replying with two whistles, as would have been appropriate. What is clear is that Stella Maris stayed along the Halifax shore and IMO remained where she was. Once the vessels passed, Stella Maris continued toward Bedford Basin. IMO continued toward the sea, still on the wrong side of the channel—and still more time had passed.

THE COLLISION

While all this was happening, Mont-Blanc was making her slow journey into the harbour. She had passed Highflyer—from which the officer of the watch noted the sloppy way she was loaded—and Changuinola, who was anchored near Highflyer, and worked her way by the Dartmouth ferries, whistling at them as she passed. (Captain Aimé Le Médec liked to let others know of his presence.) By the time she reached the narrowest part of the harbour—the part that now lies between the two bridges—Mont-Blanc had lost sight of Clara. She never did see Stella Maris, who was far too low to the water to be seen around the bend in the harbour. However, those on Mont-Blanc’s bridge could see the masts of a large ship advancing toward them (they did not know yet that it was IMO)—a ship that appeared to be on their side of the channel.

Mont-Blanc whistled once, both to let the oncoming ship know of her presence, and to make clear she claimed the starboard side of the channel, as was her right. She heard an immediate reply of two whistles, indicating the oncoming ship was not conceding the right of way. Mont-Blanc whistled again and heard another two-whistle reply. She could now see plainly that a large ship was coming directly toward her, a ship that had twice whistled it was refusing to concede the right of way. Desperate to avoid a collision, Mont-Blanc swung hard to port and blew her whistle twice to indicate that she was changing direction. She had decided to concede the right of way to IMO, just as IMO had conceded it to Clara. However, Mont-Blanc was changing at the very last minute and IMO had not replied to indicate she accepted that decision.

The problem was that even as Mont-Blanc was manoeuvring, IMO was taking her own precautions. Because she accepted the fact that Mont-Blanc was in the correct channel, she first tried to stop, blasting her whistle three times to indicate that was what she was doing. As IMO reversed her propellers, she signalled again with three more whistle blasts. Unfortunately, her forward momentum prevented an immediate stop, and the reversing of her propeller swung her bow toward the middle of the channel, directly into Mont-Blanc’s new course. The two ships collided and IMO’s bow ripped a gash three metres deep in the starboard side of Mont-Blanc’s hull. Since IMO’s propellers were already in full reverse, she pulled away from the collision immediately. A sailor named Edward McCrossan, watching from Curaca, described what he saw:

I could see the tips of the propellers of the IMO in the water. They were not in motion either ahead or reverse. I could see that the IMO had some way on her but couldn’t see if the Mont-Blanc was moving or not. The IMO ran into the French ship…. I heard no noise when she struck. As she backed out she blew three blasts of her whistle. As soon as she [IMO] backed out, I could see fire on the Mont-Blanc just at the water’s edge. It was a tiny flame at first…. The fire got bigger and bigger as the Mont-Blanc drifted towards the pier.

It was roughly ten minutes before 9 a.m., on 6 December 1917. The Halifax explosion was less than fifteen minutes away.