CHAPTER IV

THE EXPLOSION

EVEN TODAY, WITH OUR AWARENESS OF 9/11, THE FIRE BOMBINGS of Hamburg, Dresden, and Tokyo, and the use of atomic weapons against Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it is hard to comprehend the extent of the destruction of Halifax in 1917. Before the explosion, the city was a vibrant port community of 55,000 to 60,000. After the blast, one-fifth of the population was dead or injured, another third was homeless, the Richmond district of the city’s North End was destroyed or on fire, and the inner harbour was full of half-submerged and battered vessels. The railway yards were a wasteland of broken and overturned cars and damaged engines, and the naval dockyard and the army’s Wellington Barracks were a shambles. It was the same on the other side of the harbour in the north end of Dartmouth. About the only things left standing in the devastated areas of both cities were the tall concrete chimneys of the various factories. At a 1992 conference at Saint Mary’s University, scientists Alan Ruffman and David Simpson and historian Jay White showed that the explosion may not have been the most powerful explosion before the atomic bomb, but it was a contender.

The effects of the explosion were not felt all at once. First, there was a ground wave that shook buildings. Then came a shock wave that smashed windows and sent glass flying. After that, there was a hail of debris. Before the debris started falling, a huge wave tossed ships around and carried victims high onto land. Between the two shock waves, and between the shock waves and the debris, there was time to run or take cover. Then, as the survivors tried to cope with the devastation, there came what the official historian, Professor MacMechan, called a “black rain.” It consisted of a mix of oil, iron filings, and dirt, and it poured from the sky, covering everything—including the victims—in black. It pushed dirt into many of the open wounds, causing infection that would lead to death. A layer of black can still be found in the soil in Halifax’s North End.

First to feel the impact were those close to Mont-Blanc. Everyone in Niobe’s pinnace was killed. William Becker was the only survivor from Highflyer’s whaler. Though injured, he managed to swim to the Dartmouth shore. Two others in the whaler survived for a few minutes. Joseph Murphy was still alive when he was pulled from the harbour, but he died moments after he was rescued. Lieutenant Ruffles managed briefly to hang onto a plank. When Becker called to him asking if he could make it to shore, Ruffles replied, “I don’t think I can manage it.” The Stella Maris was slightly farther away, so she escaped the full impact of the initial explosion, but she was driven onshore by the force of the wave. Some of her crew were thrown into the water and drowned—nineteen of twenty-four souls died, including her captain, Horatio Brannen.

Most small craft in the area took a terrible beating. The tugs Douglas H. Thomas, and Nereid, and Roebling were severely damaged, as was the collier J.A. McKee, the schooner St. Bernard, and the patrol vessel CD-73. The tug Musquash was set on fire and drifted toward the Picton. The US Coast Guard cutter Morrill’s upper and forecastle deck port side plates were depressed, and its starboard forward rigging was carried away. Morrill was further damaged when the steamer North Wave drifted into her. The impact left open seams in her main deck, and the hurricane deck forward of her pilot house was moved slightly to starboard. On Picton, where Frank Carew and his sixty-eight longshoremen had worked desperately to cover the hatches, Carew and fifty-three longshoremen were dead immediately. Two more died within minutes. A boulder from the harbour bottom weighing more than a ton dropped on Picton and went through her upper deck.

Two days prior to the explosion, Calonne and Curaca each hired twelve men to look after horses going from Halifax to Europe. Most were to be paid $20 a month plus return transportation to Canada. The foremen were to get $100 a month. The “Agreement and Account of Crew” stated: “The said persons will be required to feed, water, groom and exercise the horses and keep stalls in good condition as directed by the Foreman in charge, also clean up ship after horses are discharged, at, or before reaching the final port of discharge and to assist in loading and disembarkation of horses.” When Mont-Blanc exploded, seventeen of those twenty-four men were killed. Two others were sent to hospital. Only five were not seriously injured. To explain why he discharged his crew, her captain wrote in his log, “ship destroyed.” These men saw Mont-Blanc on fire and even noticed her drifting close to where they were working. But, like almost everyone else, they had no idea of the danger she presented. They were still loading horses when she exploded.

Hovland was partially protected by the dry dock, but five of her crew were dead. Though she was some distance away, there were three dead and fifty injured on the British warship Highflyer. Even farther away, passengers on the Dartmouth ferries had to drop down to escape injury:

I was crossing the harbor and providentially went on deck, a thing I never do, but the day was bright and mild and I thought I would go up. I saw the fire on a ship but did not think it much, we all watched it and it grew worse and then a volume of smoke went up and flame…. I had my full senses the whole time and knew exactly what was going on when I knew there was an explosion. I with the others on deck lay flat on the deck and not one of us was scared but those who remained in the cabins were fearfully cut and bruised. I had no idea there was any damage done and when we docked and I saw the ruins of the town, I was very much surprised.

Inside in the cabin, passengers were not so fortunate. Two women whose father was crossing rushed down to meet him when the ferry docked: “We met the people coming off the boat and a dreadful scene met us. Everyone was bleeding and those less cut were supporting those less fortunate. At the tail end of the crowd came Dad. He had been sitting between two windows.” Their father was not cut, but another passenger, Flora Murphy, lost an eye from the flying glass.

On IMO, most below deck survived, but those above deck—Captain From, Pilot William Hayes, the helmsman, and the deck hands—were killed. One sailor, Sigurd Olsen Hunstok, was blown through the air from the bow to the stern. Later, his left arm would have to be amputated in three successive operations: each time the infection spread, more of his arm was removed. He returned to IMO’s home port of Sandefjord, where he became a successful businessman and learned to use his right hand—he had been left-handed. IMO itself was thrust ashore in Dartmouth and would stay there for a month, but she survived. Niobe looked battered. All of her funnels were bent, and all of her woodwork was smashed into kindling. Some of her crew had been washed into the harbour. An official report said: “Besides the damage done to the funnels, there were gaping holes in the superstructure. Stanchions, lines and blast brass protecting the gun position had been strewn from stem to stern, as though enemy fire had raked the ship. Men sprawled over the deck, dead or knocked out by the blast.”

While the Mont-Blanc disintegrated, her crew largely escaped. They were still running when their ship exploded, and just four were injured by flying debris. Only gunner Yves Gueguiner died from those injuries. All the rest survived to talk about it for the rest of their lives. The cook, who settled in Bordeaux, was always ready to share a glass of wine and recall the events that day in Halifax. One other survivor was Mont-Blanc’s cat. She escaped from the explosion minus part of an ear and some of her fur. She was later named “Halifax” and adopted by the crew of the Calvin Austin, a relief ship that came up from Boston.

HARBOUR DAMAGE

All along the harbour there was further damage. The Acadia Sugar Refinery was in ruins. Ragus was upside down. Her captain, John Blakeney, and her crew were dead. At Pier 2, the main Canadian army reception area, all the partitions were torn down. The last ship with injured from abroad had arrived two days earlier, so there were just a few soldiers on duty. One member of the Army Medical Corps staff, Quarter-Master Sergeant Ernest Carr of Prince Edward Island, was fatally injured in his North End home just before he left to report for duty. The military quarters at the pier had to be vacated. At Pier 1, the submarines, CC1 and CC2, were bounced around in the water by the force of the blast. Both broke adrift when the wave swamped them.

Pier 6, which had been set afire by Mont-Blanc, was gone. There was no trace of the schooner, St. Bernard, which had been moored there. Stella Maris was piled up on the shore. Bits of Pier 7 remained, but it was mostly wrecked. Pier 8 was demolished. Its ruins could be seen beneath the water. Pier 9, the railway terminus, was partially intact, but the sheds, tracks, and freight were jumbled together. Hilford was in that wreckage. The wave after the explosion lifted it six metres and dropped it on shore. The captain, Arthur Hickey, was washed overboard and drowned, but two crew members survived. Calonne was now alongside, her hull intact but her upper works and deck houses in ruins.

On the Dartmouth shore, the Curaca was aground, her aft part underwater. She had drifted across the harbour from Pier 8. Oland’s Brewery was so badly damaged it was never rebuilt. One of the owners, Conrad Oland, was among the seven dead. (One account says that beer from the brewery flowed into the harbour.) However, in Bedford Basin there was minimal damage. On Nieuw Amsterdam, for example, there were a few cracks in the paint and a couple of splintered doors. One member of the crew—who had his head stuck out a porthole—received a bump. No one else was even bruised.

There were a few miraculous escapes. One sailor from the Middleham Castle was blown half a mile through the air and landed, wearing only his boots, on the hill by Fort Needham. (Many survivors were minus all or some of their clothing.) The Patricia’s driver, Billy Wells, survived, even though he was injured and carried along by the tidal wave that swept over the piers. But the fire chief and his deputy were dead. Their car had been blown through the air and landed upside down. So were the rest of the crew of Patricia—Michael Maltus, Frank Killeen, James Duggan, Walter Hennessey, and Frank Leahy. The police department was more fortunate. A check of morgue records suggests some police lost parents or children, but no officer was killed.

Jack Ronayne, the reporter who had gone to cover the story, was dead. So were Constant Upham and Isaac Creighton, the men who owned stores near the docks. Upham had phoned in the fire alarm. Also dead was Lieutenant-Commander Murray. He was still on the phone when the explosion occurred. Also dead was Vincent Coleman, who had gone back in an effort to warn incoming trains. Most who gathered to look out the window of the Hillis Foundry were dead, although the foundry’s concrete frame withstood the blast. The wife of a naval officer walked through the debris to find her husband. “Derelict trams dotted the tracks,” she said, “broken telephone poles, splintered trees, doors burst open, gaping roofs and everywhere the glitter of strewn glass.”

IMPACT AREAS

At the North End station, part of the roof had fallen into the tracks. The rest had to be pulled down for safety. In the Richmond rail yards, there was devastation. Train cars with food and other supplies had been waiting to be loaded onto ships. The explosion blew over many of those cars and twisted them out of shape. A total of 374 freight cars were damaged or destroyed. Four were presumably tossed into the harbour, for they were never found. In addition, the explosion damaged eighteen sleeping cars (one-quarter of the stock) and seven military hospital cars. Five engines were also damaged, though all eventually returned to service. There were fifty-eight railway employees dead, and many more injured.

The explosion shook the incoming Boston Express, but it survived. The train was running slightly behind schedule and passed Rockingham just before 9:05 a.m. The conductor of that train was J.G. Gillespie: “The cars tilted over as far as the safety chains on the trucks would allow them to go. Then they came back. Glass was broken on both sides of the train. The engineer was thrown against the boiler-head, and injured, but was able to continue his work. None of the passengers was hurt by the glass.” Other parts of Richmond were not so lucky. The Richmond Printing Company was destroyed, leaving thirty female employees buried in the wreckage.

The Canadian army’s Wellington Barracks, just up the hill from the naval dockyard, were devastated. Major-General Thomas Benson reported to Ottawa that the wooden buildings were “totally destroyed … including the Royal School of Infantry Building.” The building containing military records had not only collapsed but burned to the ground, destroying personnel files for one of the units. The married quarters were shattered and the injured included spouses and children of military personnel. “Another seriously damaged building,” Benson reported, “is the Armouries [about 1.5 kilometres to the south of the barracks] the roof being so shattered and the girders so broken and displaced as to render use of the main floor unsafe.” A recruit described the scene at the Armouries:

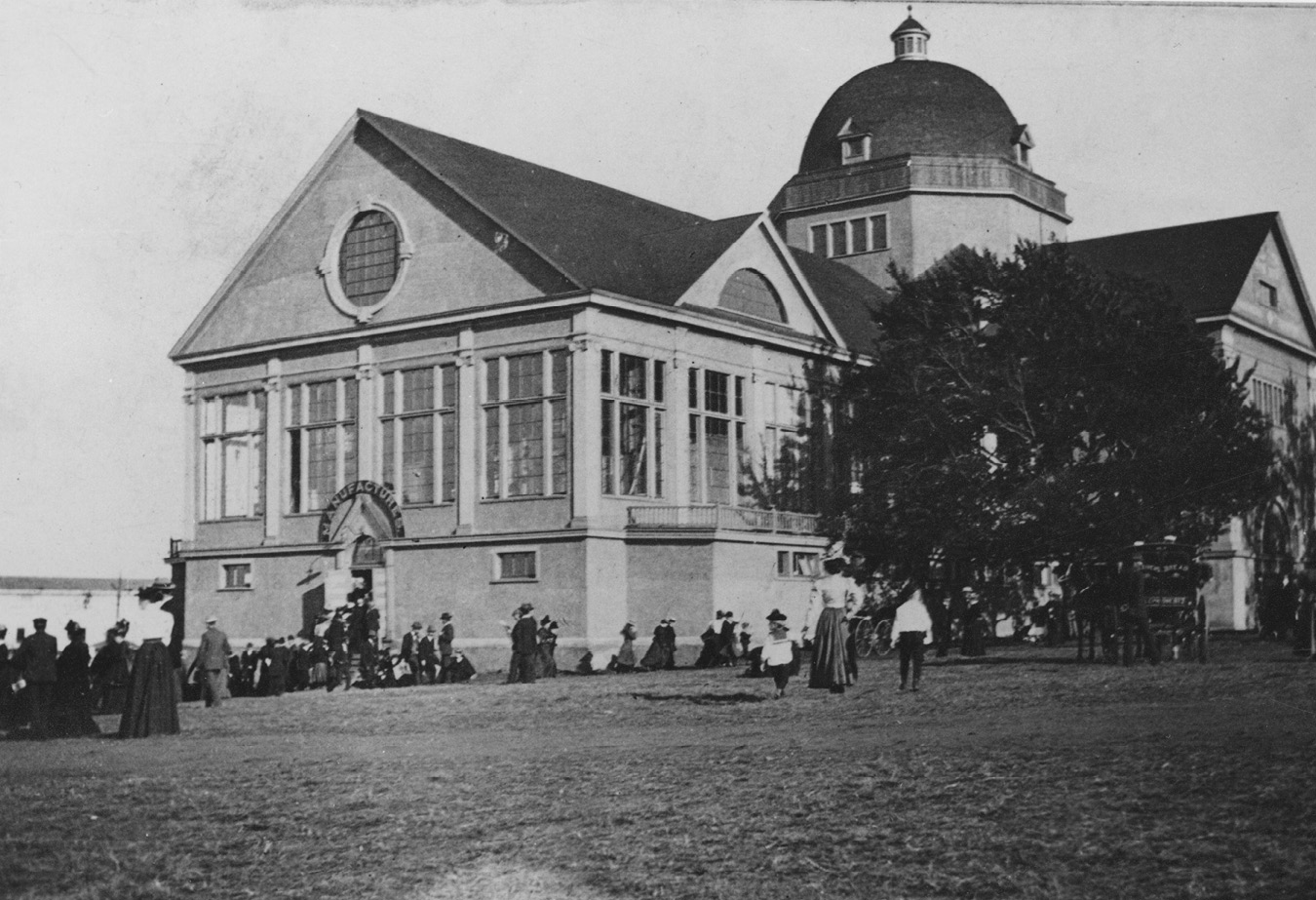

FIGURE 4.1 | Halifax Main Exhibition Building Halifax, before the explosion. Before and after images of the building illustrate the devastation. Nova Scotia Archives.

FIGURE 4.2 | Halifax Main Exhibition Building, after the explosion. Nova Scotia Archives, J.A. Irvine, Album 36 photo 6 / negative: N-5758.

Right close to the windows were three or four poor fellows lying dead just about three yards from the place where we had got the order to “about turn.” Another fellow had three of his ribs broken. The windows were blown in on them killing them instantly. There were several holes in the slated roof. The iron girders supporting the roof and the iron framework connecting it were twisted as if they were thin strands of wire…. Debris was piled high, lying all around.

Benson’s detailed report on casualties, forwarded to Ottawa on 12 January 1918, shows that 18 soldiers were killed, 502 injured, and 4 were still missing. A few of those casualties were at the Armouries; eighty per cent were at the Wellington Barracks, where there were 7 killed, 409 injured, and 4 missing among the 600 personnel present. On 15 December, Benson had reported that in the married quarters 19 of 29 wives were injured, and 49 of the 76 children. Among units stationed outside the devastated area it appears that quite a few of the personnel killed and injured were at their homes in the North End.

Howard Bronson, a physicist at Dalhousie University, worked out that there were three impact areas: up to 800 metres; 800 to 1600 metres; and 1600 metres out. He observed: “In a general way it can be said that buildings within a radius of half a mile of the explosion were totally destroyed and that up to one mile they were largely rendered uninhabitable and dangerous. No section of Halifax escaped serious damage to doors, windows and plasters.” Engineers from Boston verified this. They found practically all buildings within 800 metres (half a mile) were levelled, except an Acadia Sugar Refinery warehouse, the Hillis Foundry, and a machine shop with steel frame at the dockyard. (All three were severely damaged, however.) In buildings just beyond 800 metres, the glass was largely destroyed and the roofs, chimneys, and walls needed replacement. Farther away, the damage was almost entirely broken glass.

CIVILIANS WORST HIT

It was civilians, not sailors or soldiers, who got the worst of it. The Richmond area of the North End was a graveyard of shattered, burning homes. There were 794 homes destroyed and another 437 so badly damaged that about one-third would have to be demolished. Another 394 had minor damage, including shattered doors and windows. The death toll was close to 2000, the injury toll at least 9000, totalling roughly eighteen per cent of the city’s population. At a tenement known as the Flynn House on Mulgrave Street, every member of the four families living there was killed. Not surprisingly, the largest numbers of dead were Roman Catholics. Richmond was where working- and lower-middle-class people lived. In 1917, many of its denizens were Roman Catholics. The chairperson of the citizens’ finance committee reported later:

While every building in Halifax and Dartmouth was more or less damaged, the devastated area is found near the scene of the explosion and embraces chiefly districts occupied by workers and poorer classes. Between three and four thousand of such dwellings had been completely destroyed by the explosion or by fire.… It is evident that the destitute poor in the area will number upwards of 20,000…. It is to be clearly understood that in this estimate only the people rendered destitute are to be considered and this is the portion of the population least able to bear the loss.

Other religions did not escape entirely. At the Protestant orphanage in the North End, 27 of the 40 children were dead. The matron, Mary Knaut, herded them into the basement when Mont-Blanc exploded and they were trapped when the orphanage burned. Knaut died with them. Grove Presbyterian had 107 families in its congregation and 148 people dead, an average of more than one per family. There were 200 dead at St. Mark’s Anglican Church and 91 at Kaye Street Methodist.

At least five Halifax places of worship were beyond repair: St. Mark’s (Church of England), St. John’s and Grove (Presbyterian), Starr Street Synagogue, and Kaye Street Methodist. There was similar damage to the churches across the harbour in Dartmouth. Grace Methodist, a wooden structure, collapsed as a pile of rubble. Dartmouth Baptist Church was also severely damaged. The windows were blown out at Christ Church and St. James Presbyterian. Many people associated with these churches were affected by the explosion. The minister at Kaye Street Methodist, Rev. W.J. Swetnam, was in the manse with his family. In preparation for a concert that evening, his wife Lizzie Louise was playing the piano for their son Carman. Swetnam and their daughter, Dorothy, were watching. When he regained consciousness after the blast, the minister found his wife and son crushed under the piano, clearly dead. Dorothy was alive, but trapped in agony under a house timber. With the help of two neighbours, Swetnam desperately sawed her free.

Another Methodist clergyman, Rev. Harold Tomkinson, wrote: “To cut the story short, everything has gone. The parsonage and church are gone—our personal property and everything. Mrs. Tomkinson [his wife, Grace] is badly battered and bruised and likely to lose her left eye. Constance [their daughter] has had to have her cheeks and ears stitched. The baby’s [their daughter Joan] head has been cut. I got clear with a few face bruises.” (Constance went on to a storied career as a show girl and author, and her younger sister Joan, also an avid writer, became one of the first female stockbrokers on Wall Street.) In Dartmouth, the brand-new manse for the minister of Stairs Memorial Presbyterian Church was destroyed. Although there were no deaths in the Jewish community, a number of people were seriously injured. One congregation that escaped was Fort Massey Presbyterian, home church of the lieutenant-governor, McCallum Grant, and his predecessor, David McKeen. Its members lived in the south end of the city, away from the worst of the blast. As the annual report for 1917 noted: “The terrible explosion of December sixth dealt mercifully with this congregation. Our houses, though injured are habitable; our church, though severely damaged, stands and no family lost a single member.”

THREE SHOCK WAVES?

In addition to stating that there were three distinct impact areas, Howard Bronson, the Dalhousie University physicist, said in a paper presented in 1918 that the university seismograph showed three distinct shocks—one at 9:05 a.m., one thirty seconds later, and one an hour after that. Later scientists have discounted this. They say the first explosion was felt in two ways and that the other shock waves did not occur. Bronson himself said that there were doubts about a third shock, but it was possible some explosives had detonated on the harbour bottom and gone unnoticed. Bronson was one of Canada’s most distinguished physicists. After finishing his Ph.D. at Yale in 1904, he worked as research assistant to Ernest Rutherford. After McGill, Bronson moved to Dalhousie and became head of the physics department in 1910. One of Rutherford’s other associates was Niels Bohr, who won the Nobel Prize for his work on the structure of atoms.

Whether or not there were two explosions narrowly separated from one another, there were definitely two impacts—and there was a gap between the two. Scores of individuals not only described the two impacts, many tell what they did between the first and the second. George Adam, pastor of Toronto’s Emmanuel Congregational Church, was in Halifax campaigning for the Conservative-Unionist slate in the upcoming federal election. He was at the Halifax Hotel: “A violent tremor shook the building and I imagined that the hotel had collapsed. Three or four seconds passed, then came the terrific crash. The windows of my bedroom crashed in, frames, glass and blinds. The table and chairs were pitched over like ninepins.” Another guest, William Baxter, said he felt “a shock resembling a violent earthquake…. A few seconds later another shock was felt more severe than the first … and broke the plate glass which fell over [me] and a friend [who] was badly hurt.”

At Mount St. Vincent Academy, Catherine White noted the same phenomenon: “When the explosion occurred we were in our classroom and all of a sudden there came an awful noise. The building shook like a leaf. We thought some power plant had exploded. About a minute later, the full force of the explosion hit us and every window in the building crumpled.” White was farther away than Adam and Baxter, so she would have noticed a longer gap between the first and second explosions. Bronson, who was closer than White, but farther than Adam or Baxter, described the same experience: “At the time of the explosion, I was standing in my laboratory on the second floor of the Dalhousie University Science Building about 3500 metres from the explosion. I first felt a shaking of the building no greater than that caused by heavy blasting in the railroad cut, but it seemed to be directly under the building and I started for the boiler room, fearing an explosion there. I had gone less than 30 feet when the crash came which completely destroyed the windows and sashes on three sides of the building, broke heavy doors and locks, and even shifted partitions.”

The senior Canadian Army Medical Corps officer in Halifax, Lieutenant-Colonel Bell (assistant director medical service, Military District 6), who was presumably at his office in the headquarters buildings in the south end, matched Bronson’s estimate of a thirty-second gap. A consulting firm, Gilmour, Rothery & Company, agreed with Bronson that the gap was not entirely the result of the distance from the scene. It, too, said there were two distinct explosions. The first was the result of the gun cotton exploding, which acted as a detonator for the picric acid and TNT that exploded later.

In addition to causing damage, the explosions shattered windows all over Halifax, sending glass into the eyes of those watching the fire. Many bled to death as a result. At the officer’s mess at Wellington Barracks, several officers were hit when the window shattered. One died from his injuries. Frances Rudolf’s closest friend saw the mushroom cloud from her window and called to her sister to look. The window blew in and sent glass through one eye—the eye had to be removed. At the King Edward Hotel, close to the North End station, guests were having breakfast. “One could see the poor dead people with napkins in their hands covered with blood as they had taken them up to wipe their faces when they were cut by the flying glass.” It was the same on the trolley cars. Leslie MacDuff walked from his school to Spring Garden Road and then Coburg Road, where he could see people getting off the trolleys. “They were cut with flying glass. There was blood all over.”

Lieutenant-Colonel Bell reported: “The terrific force of the concussion even two miles from the scene of the explosion … was so great that the windows were burst in with such violence as to drive bits of glass completely through plaster walls and into doors at the far side of the room. As a result of this force and the position of the people, the pieces of glass were driven into the face; the eyes being especially affected. Hundreds are disfigured for life with ghastly scars.” This was certainly true at the Royal Naval College, where the senior class of Canadian naval cadets had gathered at the window:

All the windows were blown in, and the glass was driven with great force into the building, and was responsible for most of the injuries, a number being badly cut about the face and eyes. The partitions between the classrooms etc., being only of light construction, were knocked down by the force of the explosion and the roof of the college was damaged in several places. The part of the building that suffered most was the new wing at the North End. In this section, the roof lifted clear away from the north wall and the floor has collapsed in a remarkable way…. The gymnasium also suffered rather badly, a large piece of the steel plate from the ship … being driven through the roof, making a large hole in it, also on the floor below.

One of the cadets, W.B.L. Holms, would be known as Scarface for the rest of his life. (One source says what came through the roof was not steel plate from Mont-Blanc but the boiler of Hilford, the tug that had been picked up by the blast and dropped on the wharf.)

Because the explosion came minutes after the cadets had been called to divisions, the junior cadets had gone to the side of the building facing away from the harbour and consequently suffered mainly minor cuts. Among the seniors, Willet Brock had been looking at a newspaper when Mont-Blanc exploded and the flying glass hit him entirely on his right side. He was one of thirteen cadets to be injured. The head of the college, Commander Edward A.E. Nixon, was knocked unconscious and cut around the face—he had to be carried from the building. The seemingly lifeless body of Chief Petty Officer William King was taken to the morgue in a cart, where he awoke two days later. For those farther away or with protection, the explosion was not that bad. Most students at the School for the Blind were taking music lessons in rooms away from the harbour. One of the few who felt a strong impact was Edward Davis. He was practising piano. He recalls: “The piano first gave a slight lurch. I pushed it back. When the second gigantic crash came, this time the piano dealt me a mighty blow and sent me lurching across the room.”

THE WAVE

The explosions pushed water away from around Mont-Blanc, creating what amounted to a tidal wave. The wave tossed ships around in the harbour and washed along the shore. Joseph Cogan, the man who tried in vain to get his captain to move the Hilford, was in the engine room when his ship was lifted up and dropped onto the pier. He found himself hanging onto the rail by the wheelhouse when he recovered consciousness. His captain was dead. In a radio interview forty years later, a sailor from Niobe, Reuben Hamilton, recalled that wave:

It took place on the exact moment when I had my first foot on the ladder to go up on the next deck, you know, the companionway, I remember that, I had only one foot and in another few seconds I would have been on the upper deck. But I was knocked flat, stunned only for a few minutes, but I was unhurt. I wasn’t hurt at all, wasn’t hurt. The Niobe was permanently tied to a dock in the naval dockyard … tied with her anchor chain, huge, strong powerful…. There was this tidal wave by the force of this concussion and the Niobe was lifted up on this wave and she broke every line there was a-tied … Then she swung around away from the gangplank and, of course, again the gangplank disappeared, and there was no gangplank…. There were a lot of men pushed into the water, right then and there.

A wireless operator on Niobe, Frank Loomer, saw the same thing:

The ship was thick with dust so I couldn’t see a foot but I knew the way all right so got up to the quarter deck and gangway where a bunch of sailors were standing waiting for the rain of metal to stop…. We stood there maybe half a minute, then someone yelled to run for it, and we all rushed down the gangplank, which was tilted over 15 degrees. I had just reached the jetty when the water began to pour over it and I waded through about two feet of it for about 30 feet to high ground and beat it up the hill.… I guess that those who came after us got swept away, for the water came up so rapidly that they couldn’t have been able to stand against its rush.

When the wave hit, Roy Partridge was in a small boat: “My boat was lifted twelve feet on the crest and then was dropped straight down twenty-five feet. I had just time to close the front end of the cabin when we plunged down, head first. I thought we were all gone but my boat, although half filled, freed herself and bobbed to the surface.” David Cochrane was also in a small boat. The man he was with had his face blown off. Cochrane was found later in a coal barge. He did not regain consciousness for twenty-three hours.

BLACK RAIN

According to witnesses, it was about three or four minutes after the explosion before the final impact: black material falling from the sky. A teacher in Dartmouth, Miss M.A. Christie, said that at first she thought it was raining. She saw lumps of oily soot as large as a fifty-cent piece. There were also hard black lumps, like cinder. Survivors say it took weeks to get the black out of their skin. A passenger on an incoming train said there was a concussion, the windows burst, and then “a thick, black cloud of dust settled over everything.” Loomer, who had been on Niobe, wrote a friend, “I was as black as a coal miner and covered with dirt.” Loomer was not injured, but those who were had black dust in their wounds. MacMechan’s official history says that this oily soot, almost like a liquid tar, fell for about ten minutes, blackening everyone and everything, including the corpses, making it impossible to distinguish white from Black people. (This explains why the first bodies to reach the morgue were assumed to be from Africville.)

Since most homes in Richmond were detached dwellings, no firestorm took hold, but there were hundreds of individual fires. Along streets like Lower Barrington, Gottingen, and Russell, however, where the houses were very close together, the fire spread from one wooden building to the next. One major building, Dominion Textiles, was destroyed when sparks from neighbouring buildings blew through its damaged windows. It had been only slightly damaged in the explosion. Rear-Admiral Chambers was walking down from his house and he saw fires start and then gradually spread:

Even as we watched fires were springing up in all directions, and increasing with amazing speed. First a puff of white smoke, like a tuft of cotton wool, then a bright spark, then a raging furnace. One wondered when the flames would stop as they burrowed further and further into the comparatively intact part of town. Fortunately, the day was an extremely fine one, and such wind as there was blowing took the flames away from the better part of town; but even so the progress was truly alarming.

Chambers noted in his first report to London that the day was clear and cold, and what wind there was came from the south. That helped stop the fire from spreading. The fire reached its peak between 11 a.m. and 12 noon, and the major fire threat ended when firefighters assisted by sailors stopped it from spreading from the North End to the downtown.

There were two distinct ethnic communities in the Halifax–Dartmouth area in 1917: the Indigenous and Black communities. The first account of the impact on the Mi’kmaq was produced in 1992 and appears in the book Ground Zero: A Reassessment of the 1917 Explosion in Halifax Harbour. The research shows that the Mi’kmaq community was almost directly across from Mont-Blanc when she exploded, and that the community never recovered from the impact. As a result of the explosion, it virtually ceased to exist. The Mi’kmaq school had not yet opened when the explosion occurred. The school’s principal, George Richardson, stopped to watch the fire from Halifax before crossing on the ferry. He was killed in the explosion.

The story of the Black community has not been told, partly because records of deaths of non-whites were not properly kept. The list of dead includes such entries as “Mi’kmaq girl” or “black man,” but no names. For example, one letter about Calonne’s crew listed the names as F. Flack, A. Slade, Jack Halliwell, Arthur Moyse, and Hinds (coloured). Hinds was Joseph A. Hinds, forty-two, from Barbados. One of Calonne’s carpenters, he was the only one listed solely by his surname. Most resident Blacks lived by Bedford Basin in a settlement called Africville. Although the area was affected, few names of dead Blacks have surfaced. Both Stanley Mintis and James Allison are reported to have died as they walked along the railway tracks. Esther Roan was taken by train to Truro the day of the explosion and died in the emergency hospital at the Truro Court House the next day. And the Nova Scotia Archives now lists Aldora Andrews and Charles Henry Simonds as residents of Africville killed by the explosion. As far as can be determined, those were the only deaths in the Black community.