CHAPTER VIII

ORGANIZING THE RESPONSE

THE KEY ELEMENT IN A MODERN-DAY COMMUNITY EMERGENCY plan is an Emergency Operations Centre, or EOC. The EOC is a well-equipped place where the various emergency agencies, such as police, fire, ambulance, social services, and public works get together. It is not necessarily a place where orders are issued—“command and control” is a myth even in the military—rather, it is a place with good communications where information is shared and priorities can be discussed. It is also a place to determine who will perform a given task. For an EOC to be effective, it is crucial to have good communications and to have all key players present. Halifax, of course, had no emergency plan and no EOC, but, despite that, a coordinated response system was quickly organized—a system that included all of the elements now acknowledged as crucial to emergency response: shelter, food, transportation, and communications. As well as one that is often not recognized: the handling of the dead. The man who was responsible for that was the city’s deputy mayor, Henry Colwell.

Henry Colwell came to Halifax from Saint John, New Brunswick, as a teenager, after his father died. He took a job as a messenger to help support his widowed mother, and then worked his way up to travelling salesperson. Later, he and one of his brothers took a major gamble. With $300, they bought a business worth $16,000, agreeing to pay the remaining $15,700 in three years. One year later, they paid off the entire amount. Over the next two decades, by extending their contacts and taking trips to London to buy from the best British suppliers, the brothers built Colwell Brothers, the high-quality men’s clothing store that still exists today—Colwell’s grandson John eventually became chief executive officer.

At the time of the explosion, Halifax had both a municipal council and a Board of Control (or executive committee)—a strange adaptation of American-style politics to Canadian local government. The mayor and four controllers were elected at large, and the five formed the executive committee, with the controller who got the most votes as deputy mayor. However, unlike the US, where the executive is separate from the legislature, in the board of control system the executive members sit as voting members of council. In 1917, Henry Colwell got more votes than any other candidate for controller, so he automatically became deputy mayor. On 6 December, Mayor Peter Martin was away campaigning (he was the Roman Catholic Unionist candidate in the two-member Halifax constituency for the upcoming federal election), so Colwell was acting mayor. Acting at first on his own, and then working with a committee he helped create, Colwell played the key role in turning the initial chaos into a coordinated response. In doing so, he applied the same quiet efficiency he had showed in building his business.

It seems likely that Colwell was at his store on Barrington Street when the explosion occurred. It is clear that a little later he was at city hall. There he rounded up the city clerk, Fred Monaghan, and the chief of police, Frank Hanrahan, and took them to visit the senior Canadian army officer in Halifax, Major-General Thomas Benson. Even with what he knew then, Colwell felt that the situation in Halifax was far beyond the capacity of local government. He also felt that the first priority was to help the victims. Doing that would require transportation to move them to medical centres, and trained medical staff to look after them once they got there. The key to both was the army. Benson told his visitors that military hospitals like Cogswell Street and Camp Hill were already overflowing with civilian patients, the Citadel was trying its best to provide shelter and sustenance for homeless survivors, and soldiers were giving first aid. But soldiers could commandeer civilian vehicles for emergency use, and the military could help with the handling of the dead.

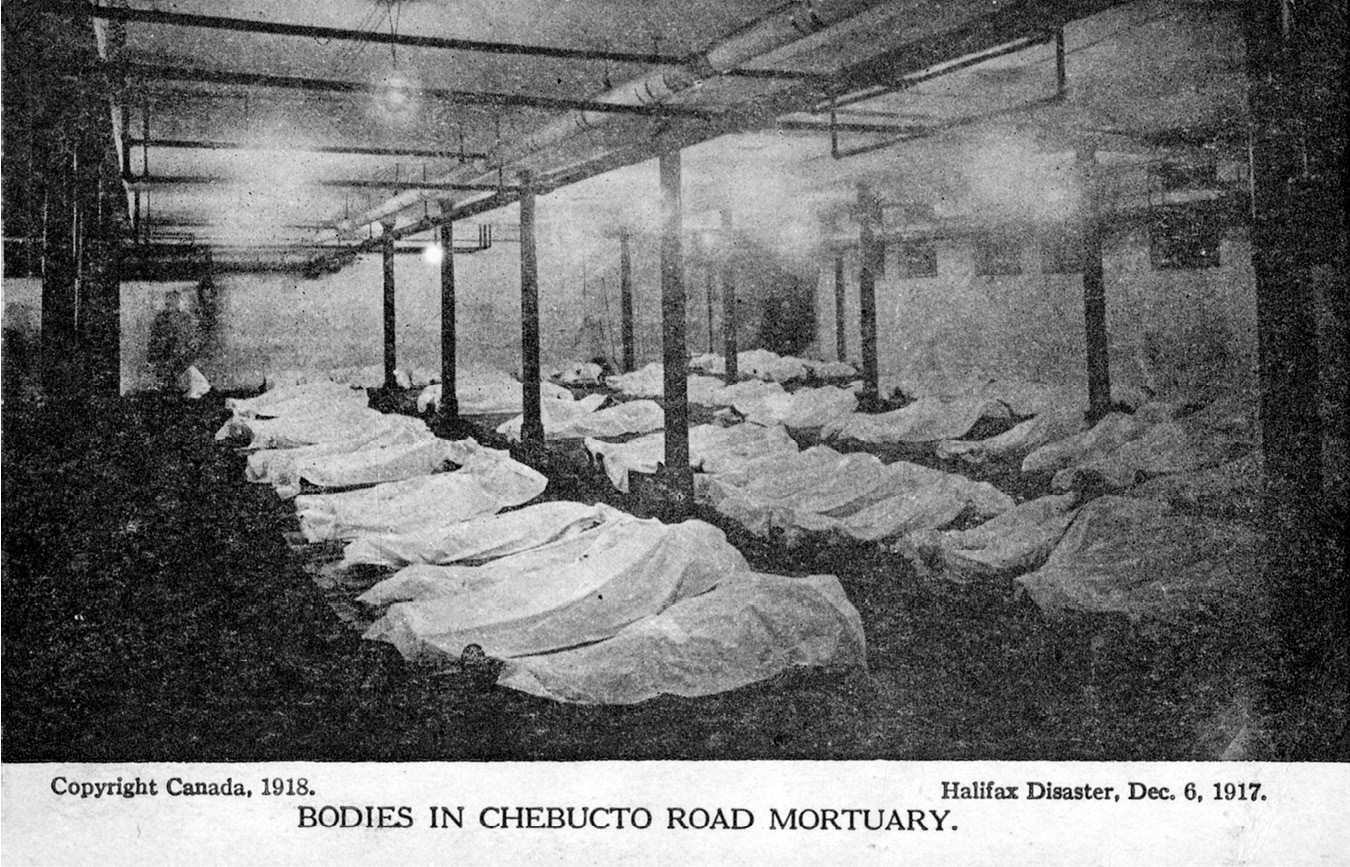

As a result of Colwell’s visit, Benson ordered units from the 1st Depot Battalion and 1st Quebec Regiment, among the CEF units quartered on the Commons, to set up a roadblock at the junction of Cunard, Agricola, and North Park streets. They were told to “commandeer all vehicles as … these would be invaluable for the removal of the injured to the various hospitals.” When the 257 soldiers of the Halifax Rifles arrived from McNabs Island, they started searching the ruins for survivors, wrapping the injured with blankets, taking them to hospital, and using blankets to cover the dead. Later, they were assigned to the morgue, a task their officers admitted “was the most revolting and hardest work.” In addition, Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph B. Simmonds, commanding officer of the Princess Louise Fusiliers, headquartered at York Redoubt, had arrived with about 100 soldiers of his unit, and started clearing bodies off Barrington Street by stacking them alongside it. There was no place else to put them. Simmonds had obtained some labels from his family’s hardware firm in Dartmouth and attached these to some bodies to show where they were found, but many bodies were moved without any attempt to indicate where they had been before they were stacked in piles.

The army’s taking over civilian cars led to a few angry exchanges, but protests were ignored, even though there was no legal basis for the seizures—martial law was never declared, and the municipality never passed any kind of emergency bylaw. The new drivers kept going for days with little rest as they carried victims to hospital, moved supplies to the various shelters, and provided a transport service from the railway terminus to City Hall and the hospitals. Typical was Lieutenant L.L. Harrison of the 1st Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery. He helped with the injured until 2 a.m., drove a senior officer around during the night, and then, at 5 a.m. Friday, started meeting trains bringing in doctors and nurses. He worked until 9 p.m. Friday—thirty-six hours non-stop. Some cars were not commandeered. When Captain Frederick Tooke, one of the Army Medical Corps doctors dispatched from Montreal, arrived in Halifax Monday morning, he noted that many drivers were women. The soldiers had been less aggressive with women, allowing them to keep driving their own cars.

Before Colwell and his delegation met Benson, a number of messages went out from Halifax reporting what had happened and calling for assistance. George Graham of the Dominion Atlantic Railway had reached his headquarters in Kentville. W.A. Duff of the Intercolonial Railway had communicated to Truro and the railway’s headquarters in Moncton, and his reports were passed on to the minister of Railways, in Ottawa. Colwell had got Duff to send another message asking for help from other municipalities. This message helped trigger a response from Nova Scotia communities like New Glasgow, Amherst, and Sydney, and from Moncton in neighbouring New Brunswick.

All of this was important, but there was still no central place where it could be established what had been done and what needed to be done. This was understandable. The explosion was catastrophic. It was not possible for any one person or organization to comprehend all that had happened. In addition, the various responses were rapidly changing the situation. Those who pulled victims from the wreckage, loaded them onto carts, and got them to hospital reduced the need for search and rescue, but increased the problems at the hospitals. The soldiers who piled bodies by the roadside, cleared the roads, but increased the need to deal with the dead. The movement of so many victims so quickly to so many locations—first-aid centres, military installations, physicians’ offices, a train to Truro, church halls, ships in harbour, the hospitals, other buildings—meant there was an enormous and growing need for information. Residents and outsiders wanted to know if their families were safe and, if so, where they were.

RELIEF COMMITTEE FORMED

At 11:25 a.m., two and a half hours after the explosion, Henry Colwell convened a meeting at city hall. Those present at the start included Controller John Murphy and two aldermen, Frank Gillis and John Furness. Controller G.A. Taylor and Alderman Robert B. Colwell (a retailer who was not apparently related to Henry Colwell) showed up later. Also on hand were Lieutenant-Governor McCallum Grant, Judge Robert Harris, and some prominent private citizens: G.S. Campbell, A.E. Jones, J. Norwood Duffus, W.A. Black, J.L. Hetherington, R.H. Metzler, George Henderson, I.C. Stewart, R.T. MacIlreith, and A.S. Mahon. Missing were Mayor Peter Martin, who was out campaigning, and Controller G.F. Harris. Harris and a friend had walked down to see the fire. The friend survived, but Harris was killed in the explosion. Also missing was the fire chief—he was dead—and someone from the medical community, all of whom were involved with treating the injured. There is no record of anyone attending from key lifelines such as the telephone, gas, or electric companies. They were busy restoring service.

Colwell said he had called a full meeting of city council for 3 p.m. because the conditions made it impossible to reach people before that. Rather than wait for that meeting, he suggested that those present—councillors and private citizens—select a committee to manage the response. He proposed that the lieutenant-governor, McCallum Grant, take the chair. Colwell said he himself would keep minutes. Everyone should feel welcome to join in. After a brief discussion, a new body was created: the Halifax Relief Committee. It would consist of Controller John Murphy, Alderman Robert B. Colwell, and four private citizens: R.T. MacIlreith, R.G. Beazley, J.L. Hetherington, and W.S. Davidson. The mayor would serve ex-officio. Colwell would be secretary.

When the larger meeting broke up, the new committee met immediately and chose MacIlreith, a prominent lawyer and former mayor, as its chair. He carried on as chair even when the committee was reorganized with the arrival of the Americans, stepping down only when the federal government took over in January. R.T. MacIlreith had a great deal of experience in public office, having served as mayor of Halifax from 1905 to 1908. To assist him and the other members of the executive committee, there was a transportation committee headed by Alderman F.A. Gillis, a food committee directed by J.L. Hetherington, a shelter committee run by Controller John Murphy, a finance committee chaired by Judge Harris, and a mortuary committee led by Alderman Robert B. Colwell.

The men who put that organization together knew each other. McCallum Grant was a successful businessman and a director of the Bank of Nova Scotia. He was also a member of Fort Massey Presbyterian Church, the establishment church, as had been the Honourable David McKeen, the former lieutenant-governor. Arthur Barnstead, who took over the morgue—his father had handled the morgue when bodies from Titanic were brought to Halifax—and A.D. MacRae, who handled registration and inquiry, were also members at Fort Massey, as were two of the men who would dominate the subsequent inquiry: W.A. Henry and Judge Arthur Drysdale. The executive committee had a good mix of the city’s religious elite: R.T. MacIlreith was an Anglican; R.G. Beazley was a successful local businessman, a Roman Catholic, and a Liberal; William Seymour Davidson was a steamship agent, a Liberal, and a Baptist.

However, Colwell, a Baptist, was the dominant player. First, he saw that a relief committee was appointed and that it had a chairperson. The mayor was a committee member, but he was not the chair. Since Martin was a Unionist candidate in an election that was splitting the country, having someone else in the chair made sense. Second, Colwell himself was secretary, which meant the job was not given to the city clerk, a man known to enjoy more than a drink or two. It also meant Colwell was the one who recorded what happened, and thus had the records necessary to show what action was required. Secretary can be a powerful position.

As the day wore on, Robert B. Colwell coordinated the response in the North End (with the fire chief and deputy dead, he was running the fire response). MacIlreith and the acting city engineer visited Chebucto School and chose it as a morgue. J.L. Hetherington selected the warehouse of John Tobin and company as a storehouse for food, which, the food committee decided, would be available free.

The Dominion Coal company and Cunard’s were distributing coal. Imperial Oil was providing oil until the supplies ran out. A line of credit had been opened at the Bank of Nova Scotia and Judge Harris told the committee it could get money “to any reasonable amount” if there were urgent needs. Despite extensive damage to its equipment and the loss of thousands of telephone lines, Maritime Telegraph and Telephone had already installed special lines to service the Halifax Relief Committee at City Hall. In addition, Intercolonial engineer W.A. Duff had a telegraph link established to the Ocean Terminals. By mid-afternoon, trains were not only arriving at the northern outskirts, but preparations were well under way to use the new line, which cut around Halifax to the Ocean Terminals by Point Pleasant Park in the south end of the city—where they still go today.

FIGURE 8.1 | R. T. MacIlreith, chair of the Halifax Relief Committee, visited Chebucto School and helped select it as as the mortuary in 1917. Nova Scotia Archives. Cox Brothers, 1918; NSA, Halifax City Regional Library, accession no. 1983-212.

While this was happening, someone—it is not clear who—organized volunteers into teams and divided the North End into zones. Then, people with cars went house to house through their districts collecting the homeless and injured and transporting them to shelters. By then, the Strand Theatre, St. Paul’s Hall, the Monastery of the Good Shepherd, St. Mary’s, the YMCA, and the Knights of Columbus Hall had been turned into emergency shelters. W.A. Major and C.H. Climo, who were assigned to one of the zones, said the children were grateful to be looked after, but many men and some women refused to leave their homes. Major said they preferred to live in one or two small rooms in their own residence than to go downtown. At one home, Major and Climo found a mother and father and seven children. While the parents tried to salvage some belongings, the children stood watching. At the parents’ request Major and Climo found a man from the telephone company who took the children out to supper. They drove back and told the parents where they could find their children.

At 3 p.m., when the committee met again, two new persons were present: Rear-Admiral Chambers and Major-General Benson. The admiral met the general after leaving the dockyard and accepted his invitation to attend. He was an astute observer and he described the scene from memory in a private memoir that he wrote less than two years later:

The conference was a remarkable experience—Held in the shattered town hall amidst splintered woodwork and floors covered with broken glass. In many cases those present had been at work since the explosion without even an opportunity to ascertain whether their nearest and dearest were in safety. Some showed traces of quick surgical attendance in the shape of plasters and bandages. I was much struck with the sane and business-like way in which the situation was faced. The difficulties were enormous, all telephonic communications were down and the roads were blocked, but I left the building with the impression that order was already beginning to arise out of chaos, and that what could be done would be done.

Given the temper of the times, it was a formidable tribute. British military personnel were not noted for their willingness to accept or even compliment civilian leadership. It was also interesting to note that Chambers did not seem bothered by the fact that four of the seven members of the executive committee were politicians. Perhaps he did not know. He was new to Halifax. Since the minutes say only that a representative of the Navy was there, Colwell apparently did not recognize Chambers either. It is not clear who the bandaged persons were, but they may have been Controller Taylor and Robert Colwell. They had been visiting Rockhead prison when Mont-Blanc exploded. The prison was badly damaged, so it would not be surprising if they were injured.

Although Chambers made no comment at the meeting, afterward he sent a private note to the lieutenant-governor, McCallum Grant. The engineers from Highflyer had picked up the crew from the Mont-Blanc and taken them on board. They suspected they might have deliberately set the fire that led to the explosion. Chambers felt that Grant should know that. Chambers also realized that the Canadian army was having difficulty meeting all the demands placed upon it. When the American ships Tacoma and Von Steuben arrived, he sent the captains to General Benson, telling them he was sure their services would be useful. As reported later, Benson asked the Americans to assist with security.

NEW ARRIVALS IMPRESSED

The executive committee held one more brief meeting that afternoon. Although most telegrams failed to make it, somehow word had come through that the Americans were sending relief supplies. R.T. MacIlreith agreed that he personally would call on the Collector of Customs to see if duty could be waived. As the meeting was breaking up, the director of the Academy of Music, John O’Connell, showed up to offer his premises as an emergency shelter. (It did open a shelter and a visiting theatre company looked after and entertained refugee children.) By the time that second meeting was held, the relief trains from Truro and Kentville had arrived, and the one from New Glasgow was a few hours away. When the passengers on those trains reached Halifax, they were shocked at what they saw, but were impressed by how much had been done. Percy McGrath recalls: “We had taken whatever medical supplies we had on hand and [on arrival] we walked the distance from Rockingham to a part of the North End station and a hotel, which, I believe, was the King Edward. After walking through debris for about the first mile, we came across a temporary roadway with dead bodies piled on each side to the height of 3–4 feet like cordwood.”

McGrath also recalls—and this was significant—that when they reached City Hall, they were all given specific assignments. Acadia’s principal, Dr. Cutten, made notes. Two nurses from the Acadia seminary, Mary Rust and Florence Saunders, were sent to care for the injured on board the Old Colony, and stayed there for eleven days. (The Old Colony, which had moved from the Dartmouth side of the harbour to Halifax, remained in service as a hospital ship.) Drs. Elliot and Allen were sent to help at Camp Hill, as were nurses Grace Andrews and Ethel Brown. A druggist, H.E. Calkin, went with them. Automobiles were on hand to move them to where they were required. The makeshift relief committee was already functioning efficiently. W.B. Moore wrote later: “I was surprised to find a better organization for the application of relief for sufferers than I had anticipated and attempts to establish order out of chaos seemed fairly successful.”

The train from New Glasgow reached the outskirts of Halifax at 4 p.m. and, by 5:40 p.m., when those on board made it to City Hall, the committee had even better arrangements: “The Nurses were sent, one half each to Cogswell Street and Camp Hill Military Hospitals. Some of the Surgeons going to Cogswell Street, Camp Hill, Nova Scotia Hospital, Dartmouth and Dr. M.R. MacDonald and a nurse to one of the first military aid stations on the city docks…. [All] the surgeons and nurses … worked the night of Thursday. In most cases, with short periods of rest they remained on duty through most of Friday and Saturday—the nurses remaining at work until Tuesday.” When the later trains arrived, they were met by soldiers from the military transport pool.

Although the Relief Committee did not meet again until the next morning, others kept working. The hospitals were still overwhelmed—many injured did not see a physician until sometime on Friday—and the transportation team had to keep meeting the incoming trains. Canadian soldiers patrolled the devastated area, one group looking for any new fires, the other searching for looters. The people who were doing the canvass of the damaged area also stayed on the job. W.A. Major said that he and his partner called at every house where they saw a light. They stopped at one house about 11 p.m.: “We came across six men sitting in a small kitchen around a stove. All had sent their women folk and children to safety. One man had his arm broken and his head damaged, and the others were more or less injured, but they preferred to stay in their own neighbourhood, and were thankful at having their lives saved and the women and children in safety.” Someone, perhaps the official historian Archibald MacMechan himself, underlined that passage.

LIFELINES

In the wake of a disaster, some priorities are obvious. They include rescuing those who are trapped, getting the injured to hospital, putting out fires, and finding shelter for the homeless. However, if a community is to start operating again, there is another priority: restoration of essential services. In addition to battering the harbour and destroying thousands of individual homes, the Halifax explosion played havoc with telephones, telegraph, electric power, and gas. Even as community leaders were trying to deal with the first set of problems, others were tackling these services. Within hours, some services were partially restored. Within days, all were well on the way to full recovery.

For the first half-hour, some local telephone service in Halifax continued, though 1000 lines were knocked out and all long-distance service was lost. Service between Halifax and Dartmouth was maintained, because the cable across the harbour had been damaged but not destroyed. At 9:40 a.m., however, after a warning from the Canadian army that there might be a second explosion, Maritime Telegraph and Telephone ordered its staff, including 165 operators, to abandon their posts. That shut down the phone service for several hours. When the staff returned, they restored service to the downtown area and between Halifax and Dartmouth, though not to the North End: “All the poles, cables, wires and telephones in the devastated area were … almost wiped out of existence, or were so broken and tangled up with the electric light and powers wires that they were of no further use.”

Long distance took somewhat longer to fix. As the company’s general manager, James H. Winfield, reported in a speech in 1920, the problem was exacerbated by the fact that all long-distance lines passed through the North End and 2.4 kilometres of those lines were gone. Those connections were eventually restored by hooking up suburban phone lines—that did not pass through the North End—to long-distance lines at Rockingham. In effect, the suburban service was turned into long distance. Other minor problems were solved by staff picking tiny pieces of glass out of the equipment and covering the holes with cotton, beaverboard, tarpaper, or anything else that came to hand. Even while it was repairing its existing service, the telephone company was meeting new demands. While some workers made urgent repairs, others installed lines for the relief effort. In addition to putting in the special lines to City Hall on the day of the explosion, MT&T put in trunk lines at the City Club when the Halifax Relief Committee moved there. It did the same for the American Red Cross and for the medical committee run by Lieutenant-Colonel Bell. When Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Low, of the Ottawa construction firm Bate, McMahon and Company, arrived to start the rebuilding process, he was immediately given trunk service.

In one way the company had been fortunate. Although many staff received cuts and bruises, just one was killed and just one failed to return to work. The one who was killed was eighteen-year-old Mary Elliott, who was at home off duty when the explosion occurred. The one who failed to show up was an operator named Daisy Shrum, who was at work Thursday morning and stayed at work until ordered to evacuate. Then she went home to Dartmouth by ferry, returned to Halifax, again by ferry, and went to Camp Hill Hospital. She was a VAD—a member of the Voluntary Aid Division of St. John Ambulance. When MT&T tracked her down five days later—they had been trying to find out if she was killed or injured—she was surprised. She thought her work as a volunteer was more important than being an operator at the phone company. It never occurred to her to check in.

Though the telephone company itself was all right, it needed power—and that was a concern. Power was out in much of the city and the power company was reluctant to turn it on for fear of starting fires. However, MT&T’s batteries would last only so long. Under pressure from MT&T and city officials, the power company agreed to turn the power back on. No fires resulted, though there were occasional blackouts for several days. Normal power service was re-established in a week. With power back on and operators back at the switchboards, there were soon long queues of people outside the main St. Paul telephone office wanting to make a call—at times the line reached to the middle of the street. Next day, when a snowstorm struck and the operators, all women, were trapped at work, they slept on their desks and turned the ladies restroom into a self-service restaurant. They posted a sign above the door—“meals at all hours”—served free hot soup provided by G.W. Colwell from his delicatessen on Barrington Street, and kept the telephone service going.

There were other problems. The gas lines were broken in so many places that the gas service had to be shut down. The streetcars were not working. All the stores and businesses that survived had broken windows. In Dartmouth, the explosion exposed water pipes. Residents in the lower part of town kept their taps running so the water would not freeze. The reduced pressure prevented those higher up from getting any water at all. Despite the problems, the physical aspect of the recovery went very quickly. For example, some streetcars were running by noon the day of the explosion (though this service would come to a halt next day when a blizzard stopped all traffic). The telegraph service had some lines open within an hour and, by late the day of the explosion, there were six lines open to Montreal, three to Saint John, New Brunswick, and one each to Boston and New York. By sending some messages by train to Truro and then on from there by telegraph, the telegraph companies were able to move 1000 messages an hour even that first week. Repairs to gas mains were finished by Sunday, seventy-two hours after the explosion. By Monday, gas service was restored to the south end of the city, as were street lights.

By using extra crews and cranes brought in from Stellarton, Amherst, and Moncton, the Intercolonial Railway managed to clear the two tracks out from the North Street station by noon Saturday, fifty-one hours after the explosion. The telegraph link between the station and Richmond was put in later that same day, and the sagging station roof was knocked down. At 6 p.m. Saturday, the Dominion Atlantic train to Kentville left from the now roofless North Street station. Even before that, trains went in and out of the south end, though arriving passengers found themselves in a wilderness. There was no south end station.

Some services were slower to recover. The postal service was out completely for four days, and it was weeks before regular mail service was back. So many homes were destroyed, and so many people had moved, it was difficult for postal workers to make deliveries. The courts did not start up again until 16 December, though when they did it was hard to believe there had been a break. The same men faced charges of petty theft and the same women appeared on offences relating to alcohol and prostitution. These charges were made under the Nova Scotia Liquor Control Act. There were no outbreaks of crime connected with the explosion. Finally, although the rest of Canada voted on 17 December, the election in Halifax—a two-member constituency—was delayed. In that election, Prime Minister Robert Borden won a majority with the help of the military vote.

Other things were all right at first and then problems developed. The coal supply, for example, lasted well into early January and then a crisis loomed. By 5 January, there were only 1500 tons held by the Dominion Coal Company, and residents were using 250 tons a night. (The consumption was higher than normal because so many homes were open to the weather.) Rear-Admiral Chambers told London that he was forced to let his coal go to civilian use (he did have some reserves) but that a crisis was approaching. The situation improved in late January when the Jedmoor arrived with 4000 tons. By then, the Admiralty had been forced to use old stocks from coal piles frozen solid in the below-zero weather.

STORM STRIKES

The day after the explosion, emergency food stations were in full operation. The morgue was starting the painful process of cleaning the bodies and searching for ways to identify the dead, and the mortuary committee had arranged to meet the owners of cemeteries. Meanwhile, the city engineer, H.W. Johnston, was appointed head of the building committee. A wire was sent to Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Low, whose company had built the military camps at Valcartier, Quebec, and Camp Borden, near Barrie, Ontario, asking him to come and help. He would direct emergency repairs and the construction of temporary accommodation for the homeless.

There was, however, a new problem. At 10 a.m. Friday, snow began to fall. By noon it had increased in intensity and was being driven by high winds. Because the air was fairly warm, the drifting snow was damp, making it difficult to clear. Even as the first storm was building, the Halifax Relief Committee authorized another key element in the response. It approved a plan by Clara MacIntosh, lady superintendent of St. John Ambulance, to canvass the devastated area. Only by doing that, she argued, would the committee have a grasp of exactly what was going on. The canvass, which is described in detail later, was carried out despite the deteriorating weather. It helped identify many of the needy, but it did not stop the flood of people coming to City Hall, which was becoming increasingly overcrowded. It also did nothing to stop the worsening weather.

By 9 p.m. Friday, the day after the explosion, there were 40.6 centimetres of snow on the ground. This completely tied up traffic in Halifax—cars and trucks were abandoned on the streets—and halted incoming trains. (The train from Saint John took seven hours to get from Truro to Halifax, averaging less than 14 kilometres an hour.) Some telephone and telegraph lines, repaired after a sleet storm the previous weekend, were down again. The streetcar company, which had begun an abbreviated service, had to give up. All the cars it got into service were now stuck in snowdrifts. The storm buried the North End, leaving the debris and the burned bodies beneath a blanket of wet, drifting snow. Saturday was worse. The temperature began to climb and a driving rainstorm hit Halifax. There were 3.4 centimetres of rain.

The storms sent ships skidding across the harbour, some dragging their anchors. The anchors tore apart the telephone cable linking Halifax to Dartmouth. Because of the storms, it was impossible to work in the harbour and contain the damage. By the time the storms ended, the existing cable was so badly torn and twisted that it could not be repaired. At that point, the company had some good fortune. It had cable in stock for an improvement in service. It used that cable for the link under the harbour. By 15 December, nine days after the explosion, the cable between Halifax and Dartmouth was replaced and telephone service between the two communities was restored.

Saturday morning, despite the rain, the mayor’s office was filled with volunteers doing their best to take down names of needy survivors on pads of paper. Then a woman typed them up, marked them “Relief Executive, City Hall,” and sent them to the agency distributing blankets or food or coal or oil. Percy Strong recalls using a grocer’s delivery wagon to do some of those deliveries: “The food was put up in baskets each containing one tin of corn beef, two tins of baked beans, one tin condensed milk, one tin of salmon, one loaf of bread, one pound of butter and a quantity of tea and sugar. Sufficient for a couple of meals.” While most orders were filled, it was impossible to keep track of who had received what, though Salvation Army volunteers typed out lists for future reference. Down the hall, other volunteers took down information about missing people. Still others tried to keep track of those prepared to take in the homeless. (One volunteer noted that most of those who did offer to help were obviously not that well off themselves.) There were also constant phone calls from the south end of the city where train after train of physicians was arriving. They expected to be met and driven to their assignments. The only way to do that was to send already exhausted horses. Motor cars could not get through. At 4 a.m., when a report came from Old Colony that a nurse had collapsed, two nurses volunteered to replace her, but there was no way to get them there. The situation was not helped by one city official who had managed to find a supply of alcohol.

MEDICAL PLAN

Thursday night, Lieutenant Harrison took Major R.B. Willis of the headquarters staff from hospital to hospital. Willis found that the hospitals were overcrowded and that there were injured in damaged buildings and temporary hostels throughout the city. He reported this to the Halifax Relief Committee, but they did nothing to change the situation. They left it up to the physicians to sort out the problems. On Saturday, however, the committee decided it had to do something about the stream of incoming physicians, nurses, and medical supplies—it was becoming a headache. Someone had to meet the trains and find places for the arriving medical personnel to stay. Since that was not a medical problem but an organizational one, the committee asked Judge William Bernard Wallace to head a medical supply committee. He asked Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Weatherbe, a permanent force officer of the Royal Canadian Engineers who had returned from a tour of duty overseas, to set up a plan. (Major Philip Weatherbe, a physician, was also involved with the medical response; he is sometimes confused with Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Weatherbe.) Paul Weatherbe helped put together a medical system that is still a model for catastrophic medicine. It had five key elements: overall control of medical personnel, dressing stations, a flying squad, a unified supply system, and emergency hospitals. (Although the committee’s formal head was Judge Wallace, Weatherbe did the work.)

First, Weatherbe arranged for relief trains to be met and for those on the trains to be sent to predetermined billets. For the first task, he got assistance from C.A. Hayes of the Intercolonial Railway, who was now in Moncton. The railway telegraph was working again and Hayes kept him informed of who was arriving. For accommodation, he found private homes in Halifax. Since the major hospitals were in the residential south end, that was not difficult—many people were pleased to take in physicians and nurses. Lieutenant-Colonel Bell billeted twenty-five in his own home. The largest number, seventy, stayed at a Roman Catholic convent on Spring Garden Road, within easy walking distance of the Victoria General, Camp Hill, the YMCA, and St. Mary’s.

Weatherbe had an enormous number of medical staff to deal with. That first day, fifty-one physicians came from places like Amherst, Antigonish, Bedford, Hantsport, Hopewell, Mulgrave, New Glasgow, Petite Riviere, Shubenacadie, Truro, and Wolfville—all in Nova Scotia. And from places like Bathhurst, Campbellton, Fredericton, Moncton, Plaster Rock, Saint John, and Sackville, in New Brunswick. Another seventy-two came from the Canadian Army Medical Corps. Overall, there were 311 physicians involved in the initial response—and that does not include US or British naval personnel. There were also 459 nurses.8 To handle this many staff, Weatherbe needed and got the full support of the army. His assistants were Captain T.J. Byrne, Canadian Army Medical Corps, and Lieutenant J.G. Rycroft, Royal Canadian Garrison Artillery, a highly regarded instructor who had transferred from the British artillery in 1907 and trained gunners for both the garrison and overseas service.

Because it was far from clear whether all the injured survivors had been recovered, Weatherbe arranged for a medical team to be on stand-by at City Hall. These physicians were ready to answer calls for medical help, whether those came from search parties, from hostels like the one at St. Paul’s Church hall, or from private homes. “[All] cases requiring medical aid—seventy-five or eighty a day—were … without exception, attended to within one half hour at the latest from the time the call was received…. Not including cases attended at the dressing stations or hospitals, upwards of 400 cases were given personal attention from the morning of December 8th to the night of December 12th by doctors dispatched from the medical relief office at City Hall. Every doctor dispatched to attend a case reported to the office immediately on the completion of his visit, and was then ready to go out on another call.” Since many of those physicians were from out of town and did not know their way around, the committee asked cadets from the Halifax Academy to act as guides. Howard Glube recalled:

Within a couple of days I was called out as a guide because the Halifax Academy had a cadet corps—all the males in the school, grey and white uniforms we all wore. After the explosion we were mobilized and we had to report to a centre depot with a band around our arms, a Red Cross band, to act as guides to the doctors who had come from Boston, New York and Montreal. My job as a kid was simply to guide the doctors from outside the city, from the States and Montreal to locations that calls had come in and that a doctor was needed—I was already working as an errand boy in a jewellery store on my bicycle. I knew every street.

In her book, Shattered City, Janet Kitz says that one of the first to make house calls was Philip Gough, a veterinarian. Driven by Howard Glube’s older brother, Joe, Gough went house to house, dressing wounds and arranging for transport to hospital if a person’s medical needs were beyond his skills.

On Friday and Saturday, teams of volunteers visited the devastated area and made notes of the problems they encountered. St. John Ambulance volunteers followed up on these notes. Equipped with kit bags covered with oilcloth and filled with first-aid supplies, they assisted people with minor injuries and sent word to the medical relief committee when something more was required: “wounds requiring stitches, fractures, serious burns, removal of glass from eyes, etc.” When these people visited one home, their presence would be reported to neighbours. Others would arrive at the home and it would become a miniature dressing station. Realizing the effectiveness of this approach, Paul Weatherbe added another element to his medical response plan. Using a number of buildings just outside the main devastated area, he set up fourteen treatment centres—in effect, making the informal dressing centres formal. A 1914 map shows these were spaced around the North End in a perfect semi-circle. (One was the home of veterinarian Philip Gough.) Treatment was also provided at St. Mary’s Hall, St. Mary’s College, Halifax Ladies’ College, the Knights of Columbus Hall, the Halifax Dispensary, the Convent of the Sacred Heart, Amanda Private Hospital (Dr. Ligoure’s house), and St. Paul’s Hall. The Old Colony, now moored on the Halifax side of the harbour, housed 150 convalescent patients and gave outpatient service to those it took on board the day of the explosion.

The fourth element in the plan was a medical supply system. At the Technical College on Spring Garden Road, more than two-thirds of the windows were shattered and some heavy oak doors were split down the middle. A few partitions were down and there were pieces of glass sticking out of the walls. However, the building was structurally sound and, after some make-shift repairs, was made headquarters for the medical supply system. It involved forty-four people and was run by F.H. Milburne of the Canadian Red Cross. He came in on the special train from Saint John, bringing with him all the supplies in that city that had been waiting for shipment overseas. On a twice-daily basis, Milburne’s centre provided supplies of all kinds, including drugs, to the hospitals, the dressing stations, and other places looking after the injured. When it started up, it acquired all the stock of the Halifax Branch of the National Drug & Chemical Company. Later, it got extensive supplies from the T. Eaton Company. (Eaton’s also sent its head druggist to assist.) Deliveries were made using two automobiles and drivers supplied by the Canadian Commercial Travellers Association on a volunteer basis: “The hospitals were visited twice daily by two members of our staff, and all their requisitions were filled the same day…. We found some slight difficulty in securing small surgical instruments which, we found, were greatly needed…. Kept two others employed delivering material to all the hospitals and dressing stations, maintaining a large prescription department, employing three registered pharmacists and other help, and was the chief basis of medical supplies.” What the centre did not have, it made. A team of Red Cross women volunteers wrapped and rolled bandages as required. They also sewed cloth into sheets and pillow slips.

The service did not confine itself to medical supplies. As the victims were discharged from hospital, they were clothed. That included everything from mitts to underwear, boots to sweaters, dresses to suits, ties, handkerchiefs, and braces. Records show that supplies were delivered to fifty-seven different locations; not only hospitals and dressing stations, but places like the St. Paul’s Hall, Imperial Oil in Dartmouth, and the School for the Blind—everywhere injured were being treated. Overall, 801 people were supplied with clothing; the largest group was 178 from the YMCA. The supply centre stayed open until mid-February. There was one other element in the plan: emergency hospitals. This story is told later.

REGISTRATION AND INQUIRY

With so many dead and so many missing, the city was flooded with telegrams asking about particular individuals. The day after the explosion an Information Bureau was established in the city clerk’s office. Its role would be to handle queries from outside Halifax. Locating people was not easy. In some parts of the city, all that was left was charred ruins. There was no one left—no occupants, not even a neighbour, to say who had gone where. Even in areas where the damage was less severe, many people still could not be found. Because of damage, including smashed windows, they had moved elsewhere. There were no signs saying where they had gone. (After the Kobe Earthquake, some residents left notes saying where they were. One Canadian wrote a note, put it inside the plastic cover of a tennis racket, and propped the racket up in the ruins.) It was not just the outsiders who were searching for information. Survivors would wander through five or six hospitals looking for their relatives. If they were lucky, they might find out they had been sent to Truro or, later, to New Glasgow.

To cope with the problems of registration and inquiry, a committee was formed with A.D. MacRae (chair), R.G. Burell, W.I. McDougall, A.S. Mahon, and J.A. Clark. The committee published a notice making three requests:

- That all parents and guardians seeking lost children and all persons who are housing lost children are requested to call at the City Clerk’s office and Register.

- All persons who are homeless or need shelter are also requested to register with the City Clerk when they will be assigned quarters as soon as possible.

- All persons who are willing to provide accommodation for sufferers are requested to file their names, together with accommodations available with the City Clerk.9

One registration centre was the YWCA, where Josephine Clark and Helen Wright both lived. Every day, as soon as they got home from work—the only day they missed work was the afternoon of the explosion—they sat at typewriters and took down information about those who were looking for someone. “We worked there after work for about a week. The look on their faces … they were just so absolutely beside themselves with grief and worry. They couldn’t find their people. We just put it on blank paper in a typewriter—their name and who was missing.” Eventually this process became more formal. The registration committee set up a registration centre and printed forms to be filled out.

Many people took a more direct approach. Many put a note in the newspaper stating that they were all right and where they were. The following heading, for example, appeared in the Echo on 12 December: “INFORMATION FOR THE BENEFIT OF FRIENDS.” This was followed by notes like: “Leo Pettipas, Bloomfield Street, is all right”; “Hector McKinnon, C.G.R. brakeman, late of 37 Duffus Street, is at 11 Henry Street, with a fractured rib”; “John Munroe, 3 Ross Street, is alive and has one daughter at the V. G. Hospital”; and, “D.M. Matheson (teacher) and family are living. His daughter is badly injured.” When a reporter from Providence arrived in Halifax, he was handed 150 telegrams from Rhode Island, all seeking information about family members. He persuaded two local residents to help him and set to work. The reporter was not the only one searching. Soldiers in Europe wired home asking about their relatives in Canada. Some news was good. Often it was bad: “Regret Mrs. Albert Thomas Smith severely injured, three children severely injured, two others slightly injured,” or “Regret to have to advise you, wife injured out of danger, boy killed.”

Inquiries about missing persons continued for months. On 28 December, Lena Green wrote to the Truro Hospital asking about her father and brother, Edward and Calvin Green. The Truro Central Relief Committee replied that it had no information about anyone named Green. It is not clear why that letter went to Truro. Edward Green, sixty-nine, and his son Calvin, thirty-four, were both killed in the explosion and were among the bodies registered at the Chebucto School morgue. Lena Green herself was badly injured and had been unable to write earlier. Another inquiry to Truro came from William Wright of English Corner. Mr. Wright wanted Joseph McQuade to know he would help him in any way he could. The letter was not delivered. McQuade had died in the explosion.

By the time forty-eight hours had passed, it seemed as if things were getting organized. There was a functioning relief committee that was making what appeared to be all the necessary decisions. There were subcommittees dealing with food and clothing and transportation and the morgue. Fuel was being taken care of. So were the medical needs of the community. The city had arranged a line of credit. On Saturday, however, the first Americans arrived from Boston. As will be seen later, they would persuade Halifax within a matter of hours to change almost everything—and not necessarily for the better.