CHAPTER XIV

THE AMERICAN LEGEND

IN Burden of Desire, HIS NOVEL ABOUT THE HALIFAX EXPLOSION, Robert MacNeil has one of his characters comment on the response to the explosion. The woman disparages what the Canadians did, then remarks, “I think the American man, whoever he was, really straightened them out. He gave them the push they needed. Now, they [the Canadians] have some organization.” The comment by MacNeil’s character is of course fiction, but it accurately reflects a myth about Halifax: it was the Americans who brought order out of chaos and rescued their beleaguered Canadian neighbours. It is true the American response was quick and generous, but it is also true that it was less positive than legend would have it.

If the truth is so different from the legend, why has the myth persisted? Why do people not talk about the first-class job the city did in creating a relief organization? Why is there not greater awareness of the incredible medical system that was put together overnight? Why do people remember the Americans instead of the women who did the initial canvass in the North End? Why does Prince’s thesis concentrate on business recovery instead of on the incredible job done by individuals and civic leaders? Why does everyone remember the aid provided by Massachusetts, but not the aid received from neighbouring Nova Scotia communities before anyone from Massachusetts arrived? Why does no one recall the initial response from Maine or the response by the US Navy, which occurred long before the first Americans arrived by train?

There are a number of reasons why what really happened is forgotten and why the myths persist. One is that the initial informal response was never properly documented. There are no records telling of the hundreds of individuals who rescued those who were trapped in the wreckage, or of the thousands of people who took care of their own needs and also took in their neighbours. In any case, even if writers or researchers came across such accounts, they would need to know a great deal about the reality of disaster to see a pattern. That understanding did not develop until well after the Second World War, more than thirty years after the explosion. However, there are records of the response from Massachusetts, Maine, and Rhode Island—not only in the formal reports filed by those states, but in media accounts published at the time.

A second reason why the role of the Americans has survived as such a strong image of what happened in Halifax is that Abraham C. Ratshesky of Massachusetts, and those who came with him, had a major influence on the response. They managed to persuade the Canadians to make changes to the management of the relief process, changes that gave the impression that their advice had created a new organization, not altered an existing one. Despite the weaknesses in their approach, they played a key role in the administration of emergency medicine. Everyone who was treated in a hospital staffed by Americans—noting that their patients were less seriously injured and thus more likely to survive—remembers what the Americans did for Halifax.

A third reason why the American myth survives is that the Americans were very good at publicizing what they did. The team from Massachusetts, for example, was accompanied by reporters, and Ratshesky took good care to make certain the reporters had lots to write about—not just after his team reached Halifax but also while it was en route.

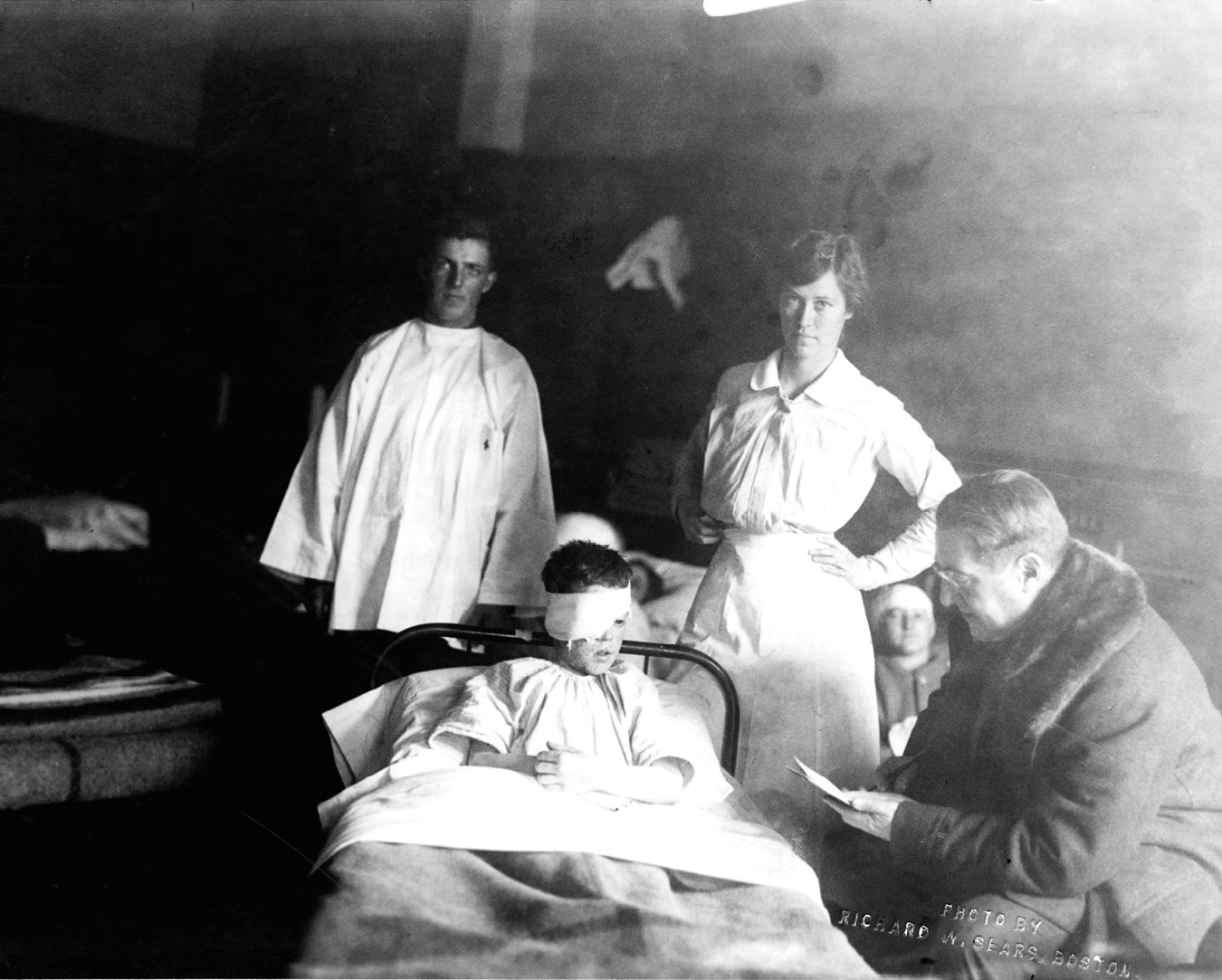

FIGURE 14.1 | Massachusetts’ expedition leader Abraham C. Ratshesky (seated right) visits an injured child in Halifax. The Americans were very good at publicity. Wyner Family Jewish Heritage Center at the New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

It would be unfair to say those reports carried false information about what the Canadians were doing and had already done, but it is true the reports contained mainly positive material about what the Americans were doing. As the chapter on the media will show, that publicity not only affected what American newspapers reported about Halifax, it played a significant role in shaping the world’s impression of what was going on in Halifax after the explosion.

There is, however, a fourth and more important reason why the American legend persists. The Americans recognized some of their early shortcomings and took some pains to acknowledge and correct their faults. In short, the Americans may have made mistakes in Halifax, but they learned from them and ended up doing something so impressive and so sensitive that the memories of American involvement are positive for very good reason. These positive achievements form the basis of the legend that the Americans accomplished much. For that, they deserve all the credit they have received.

RATSHESKY

The man who embodied the initial American attitude in its response to Halifax was Abraham Ratshesky, the personal representative of the governor of Massachusetts and one of that state’s most powerful political figures. Ratshesky did not come to Halifax merely to assist. He came to show the Canadians how to get things done. He was chosen for the job because he had already been involved in relief expeditions to Chelsea and Salem, two Massachusetts communities that had been hit by serious fires. Those fires left many people homeless and caused a few deaths, but they were minor incidents compared to what happened in Halifax, which was a catastrophe, not a disaster. However, Ratshesky did not know that, and those he dealt with in Halifax did not know it either. His experience impressed all who met him.

The son of immigrant parents, Ratshesky defied his father’s wish that he become a lawyer (he had been sent to the prestigious Boston Latin School). He dropped out of school and joined the family clothing business. He was so successful that in 1895, when he was thirty years old, he and his brother founded the U.S. Trust Company, which operated in Boston as a bank until 2003.14 During that same period, Ratshesky found time to serve on the Boston Common Council and in the state senate, and to attend four Republican conventions as he helped rebuild the Republican Party in Massachusetts. By 1917, Ratshesky was a philanthropist, wealthy enough to buy a house and donate it to the Red Cross for its state headquarters, and wealthy enough to start the Beth Israel hospital fund with a personal gift of $200,000, which in 1920 was a great deal of money.

In his report to the Massachusetts governor, Ratshesky says that when he arrived in Halifax from Boston forty-eight hours after the explosion, “an awful sight presented itself—buildings shattered on all sides; chaos apparent; no order existed. Everything was in turmoil. The first necessity was organization.” Ratshesky says he and his colleagues did not want to appear as intruders, but it was imperative to create an effective response organization. When Samuel Henry Prince completed his doctoral thesis on the explosion in 1920, he put forward the same view. Prince said there was no emergency plan in Halifax and that the city did not put together an effective response until Ratshesky arrived: “When Mr. Ratshesky of the Public Safety Committee of the State of Massachusetts came into the room it was the coming of a friend in need…. Only nine hours later, the Citizens’ Relief Committee was ready, and a working plan adopted, and from it came a wonderful system worthy of study by all students of emergency relief. With the coming of the American unit … the systematic relief work may be said to have in reality begun.”

C.C. Carstens echoed that in the American journal Survey: “Never before in any extensive disaster were the essential principles of relief so quickly established as in Halifax. In less than twelve hours from the time the American unit from Boston had arrived, the necessary features of a good working plan were accepted by the local Relief Committee.”

It is easy to understand why Abraham Ratshesky felt that something had to be done. When he arrived outside Halifax on Saturday morning, his train was held up for four hours until snowplows cleared the tracks. Halifax was still digging itself out from under the blizzard. When at last the train reached the city’s south end, no one was there to meet it. When Ratshesky and his colleagues finally got a drive to City Hall, the car smelled—it had been used to transport bodies—and the driver was depressed. He had lost his wife and four children in the explosion. At City Hall, phones were ringing, victims were wandering around, volunteers were taking notes or typing, and Boy Scout and cadet messengers were scurrying in and out. No one seemed to be in charge. Neither Mayor Peter Martin (he was back but laid up at home with bronchitis) nor the chair of the Halifax Relief Committee, R.T. MacIlreith, was anywhere to be seen. Not surprisingly, Ratshesky and his colleagues had the impression that the response was in chaos.

In fact, they did not see the worst of it. Because their train went around Halifax, they did not see the devastated area of the city, where many victims were still huddled in basements trying to keep warm and where charred bodies were buried under the drifting snow. They did not see the shelters where some of the 20,000 homeless were being cared for, or the hospitals where seriously injured victims were awaiting surgery. Yet their first impressions were misleading. While there were many problems that would take weeks, even months to solve, much had been accomplished already. Volunteers had banded together to rescue the injured and transport them to hospital. Officials from the Dominion Atlantic and Intercolonial railways had used the railway telegraph to call for help and put together special trains to bring in badly needed medical personnel and supplies. Prominent citizens had formed a relief committee and appointed persons to handle such key functions as food, shelter, fuel, transport, medical care, and a morgue. Bank credit was established. The phone system was working and there was power in the undamaged part of the city. More significant, there had been one full canvass of the impact area and a second was under way that day.

Given these advances, why were Ratshesky and his colleagues so convinced nothing had been done? The answer is that while he had seen the impact of major fires in Chelsea and Salem, Massachusetts, Ratshesky had seen nothing even close to Halifax. One-fifth of the city’s population had been killed or injured. Nearly half of the rest were homeless. There were hundreds, perhaps thousands of people trying to find lost relatives. There were hundreds of burned bodies in the wreckage. The IMO was lying wrecked on the Dartmouth shore and the Hilford was piled in debris by the wrecked railway station. With so much carnage and so many visible problems, it is not surprising Ratshesky—and others who came later—thought little had been done. Things were so bad, it was impossible for them to realize that forty-eight hours earlier they had been much worse.

CHANGED STRUCTURE

Although no one from the city was there to greet him when his train arrived, Abraham Ratshesky soon found a welcome in Halifax. This was the result of a chance encounter with Edna May Williston Best (Sexton), who, on hearing of the disaster, had joined the Boston train in Fredericton, where she was campaigning for Union government in the upcoming election. Wife of Frederic Sexton, founding principal of the Nova Scotia Technical College, she was an activist in women’s rights, and especially the promotion of technical education for women; she was a graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Best had thrown herself into the war effort as a vice-president of the all-women Nova Scotia chapter of the Red Cross, whose members produced very large quantities of such items as bandages, bed linen, and pyjamas for military hospitals. (In the wake of the explosion, they looked after the purchase and delivery of supplies for each of the fifty-seven temporary hospitals and dressing stations.)

When the train was held up as it approached Halifax, Best got off and walked (“had to ‘skedoodle’”) into the city, encountering C.A. Hayes from the Intercolonial Railway. She told him a special train from Boston had arrived, and Hayes, who was a native of West Springfield, Massachusetts, immediately went to greet the people from his home state. Telling Ratshesky how pleased he was to see him, Hayes mentioned that the prime minister, Sir Robert Borden, was in a private car nearby. Perhaps Ratshesky would like to meet him? Ratshesky said he would be delighted to do so. (He had already noted in his diary that he had seen the prime minister out for a morning stroll.)

Hayes then went to the prime minister’s railway car and told Borden about Ratshesky’s arrival. Borden went over to say hello. The two men hit it off immediately. Both men came from the political right, and both had struggled to build parties that were in disarray. Just as Borden had led the Conservatives out of the Canadian political wilderness, Ratshesky had helped build the Republican Party in Massachusetts. As soon as Ratshesky mentioned his experience at Chelsea and Salem, Borden was impressed. Like anyone experiencing his first catastrophe, Borden was shaken by what he had seen. Now he had a new and compatible colleague who had experience and was prepared to use it. Borden suggested they go together to City Hall. Ratshesky suggested Hayes, Major Harold Giddings, and John Moors of the American Red Cross join them. A few minutes earlier, Ratshesky felt snubbed. Now he and his key associates were heading to City Hall with the prime minister of Canada and the head of the Intercolonial Railway.

After a quick look at the seeming chaos at City Hall, Ratshesky suggested it might be better if the group went somewhere else to talk. Borden agreed. They moved to the City Club, taking along Hayes, Giddings, Moors, and the only two people with official status they had seen at City Hall—Judge Harris, chair of the relief committee’s finance committee, and Lieutenant-Colonel Bell, the army’s chief medical officer. Ratshesky was free to put his ideas to a group that included four people from Massachusetts, one from the existing Halifax Relief Committee, one who had been left out of the initial medical planning, and the prime minister of Canada. An added benefit was the absence of local politicians.

In a private room at the City Club, Ratshesky told this small but influential group that a committee of citizens must be selected to run the response process. He said this committee should be formed at a meeting of community leaders. From that group, a smaller management group should be selected. Since this is exactly what had been done, it is not clear how Ratshesky managed to sell this entirely unoriginal idea. Perhaps he was deliberately trying to oust the politicians and municipal officials from the relief structure, or maybe he was merely ill informed about what had happened before he arrived. Whatever the reason, Ratshesky sold Borden on his proposal, so that afternoon, on Borden’s initiative, a second and larger meeting of citizens took place and a new committee was appointed. The original committee had seven members, the new one had twenty-two, and then, a few minutes later, twenty-five. At American insistence, three were added: May Best; Agnes Dennis, president of the Nova Scotia Red Cross and wife of Senator William Dennis, publisher of the Halifax Herald; and May McCurdy, another vice-president of the Red Cross and wife of F.B. McCurdy, the Halifax financier and Member of Parliament for the Nova Scotia riding of Queen’s–Shelburne (he was also parliamentary secretary for the minister of Militia and Defence). Eventually, the committee expanded even more.

Next, a new managing committee was chosen. It consisted of seven members; a quorum could comprise just three persons, providing one of the three was chairperson or vice-chairperson. There were fifteen subcommittees: the old ones of transportation, food, clothing, shelter, registration, medicine, finance, and the morgue were still there, but to those were added new ones for rehabilitation and reconstruction, which would supervise the recovery process and the rebuilding of the North End. There was still a committee for information but none for publicity. It was not until 11 December that anyone suggested the media should be kept informed.

R.T. MacIlreith was still chairperson, J.L. Hetherington still ran shelter, and Judge Harris still ran finance. Ralph B. Bell, who had taken over H.S. Colwell’s role, stayed on as a full-time secretary. Clara MacIntosh was still a member, though not chair, of two committees. But the only politician now running a committee was Alderman F.A. Gillis, with transportation. The two mayors were still ex officio members of the executive committee, but they rarely attended. Most significant, the new key committees of rehabilitation and reconstruction were run or staffed by Americans. Other Americans were “advisors.” The organization set up by Controller Colwell was dismantled.

THE AMERICAN PLAN

At the time of the Halifax explosion, J. Byron Deacon of the American Red Cross was writing a text on community recovery. He had very clear ideas of the impact of a disaster and what should be done in the aftermath:

With scarcely less rapidity than the advance of the flames or the flight of the refugees comes the formation of relief forces, first within the ill-fated city itself and then, as the news of the calamity spreads … in other cities towns and states…. No doubt in the very first few days following disaster, these little bands render substantial help in meeting the great press of obvious and immediate needs but their period of usefulness is short-lived and by continuing to maintain a separate existence after it has passed, they seriously hamper the execution of more comprehensive relief measures.

The imperative first step in the organization of the relief forces which must be taken by the fire-stricken community is the appointment of a provisional central relief committee. The membership of this committee should include citizens of such commanding prominence as to assure the entire confidence of the community.

Deacon said the committee must include women with broad experience in philanthropic and civic work, “since they more than any other group in the community know the helpful resources of the city and how to invoke them on behalf of those in distress.” This explains why the Americans were so insistent that women be on the management team.

Reinforcing the myth that disaster victims are a mob in need of control, Deacon said it was essential that “the military are called out to keep order, and to be responsible for feeding and sheltering refugees.” He said that the senior military officer should be given the power to seize supplies. Saloons should be closed, the sale of liquor prohibited, and looting severely penalized. “The city should be placed under martial law.” Deacon said many victims, whom he called “refugees,” would take shelter with relatives or friends or be taken in by strangers. Others would go to churches, schools, and other public buildings. “These people,” he said, “must be marshalled and colonized in refugee camps, at first in tents and later in frame barracks and inexpensive small cottages.” People must not be allowed to take care of their own needs.

Then he came to the crunch: “Accurate information regarding the present and previous income of each family, its physical conditions, previous occupation, amount of losses, resources in savings, insurance, real property, ability and inclination of relatives to help … is the essential basis for determining whether rehabilitation grants should be made and in what amount and for what purpose.” He said that much of that information could be obtained by interviews with the victims, but that other sources must be tapped.

Before the Americans arrived, attempts at control and coordination were not all that successful, partly because there were so many people in need, partly because so many organizations, including the various churches, were doing things on their own. There was in fact some friction among the churches. There were also some problems created by the fact that all aspects of the response were run at the City Club. Spurred on by Deacon’s views, Abraham Ratshesky was determined that the relief effort would be under much tighter control:

We did not come here from Massachusetts to take control of any of the relief activities, but we came to help and to give to the city of Halifax, if wanted, the benefit of our experience in handling serious fires in our own land. I feel that a great step forward was made today and it means that every drop of medicine, every piece of clothing, every tool, in fact everything, will be put where it is needed most urgently in the quickest possible time.

Ratshesky also had another goal: a change in the philosophy of relief. The Canadians had been handing out food, clothing, and fuel to anyone who asked. The Americans were appalled. They believed people should not receive aid unless they had no resources of their own. That was J. Byron Deacon’s approach and it was the philosophy of Prof. Franklin Giddings of Columbia University, who later supervised Prince’s thesis on the explosion. “One thing is certain,” Giddings wrote. “Our social workers and our uplift organizations do not know what results they are getting and by what methods they are getting them, in the same rigorous sense in which a well-managed business organization knows…. The major value of scientific study is moral … nothing but the scientific study of society can save us from the humiliation of obtaining money under false pretences.”

Giddings believed that social workers have to monitor social assistance or people will cheat. It is the job of social workers to watch for and catch the cheaters, saving them from sin. Applying that in Halifax meant meticulous investigation of every potential recipient. It meant another round of questioning: not informal chats, but detailed questioning based on carefully prepared interview guides that probed not only what was wrong, but what resources the victims had before the explosion and what resources they could call on, such as money in the bank. Ratshesky, in other words, had persuaded the local community to adopt Deacon’s approach to disaster relief and Giddings’s philosophy of social welfare. That is why there was a new and tough-minded approach to social welfare. That is why the new questionnaires were long-winded and formal. That is why the relief workers started asking for personal financial information. That is why there was now a blacklist of victims suspected of cheating the system. And it is why, a few weeks later, there was a victim revolt. Ratshesky and his colleagues had been in Halifax only a few hours, but they had pulled off a major coup. The fact that it left a sour taste all through the North End was not their immediate concern. They thought people receiving assistance were cheaters anyway.

In an unpublished book about the explosion, journalist Dwight Johnstone, the friend Samuel Henry Prince took sleigh rides with, described the result as inhuman: “Sentiment, the salt that preserves the humaneness in social work, is squeezed out between the pages of the card catalogue; and the work often degenerates into a cold professionalism where the heart interest in any ‘case’ is conspicuous by its absence. Something of this was seen in Halifax and criticized accordingly.”

Johnstone was not the only critic. This new approach to relief caused so much friction that local politicians (now happy they had been bumped off the committees) turned against the Halifax Relief Committee. Before long, the volunteers, worn out and under attack, wanted out. And, eventually, so did the Americans.

To be fair, the concerns that developed in Halifax were not entirely the result of the new structure and American–Canadian tensions. The explosion put 1500 families, or roughly 9000 people, on the relief rolls. By mid-January, 8000 people were in hostels or sharing accommodation with others. Another 1000 were still in hospital. That was 15 to 20 per cent of the city’s population, which was overwhelming. It was no wonder there were difficulties deciding what should be done and how.

BLOW YOUR HORN

There was, of course, another reason why the American legend persisted: the Americans tend to blow their own horn and, with lots of American reporters present and hungry for copy, it was easy for them to do that. The American version of the creation of an emergency hospital at Bellevue, for example, makes it sound like an entirely American achievement. Ratshesky says that Major Harold Giddings and Lieutenant-Colonel Bell, “acting at my request … found a large building near the centre of the city known as Bellevue.” The minutes of the Halifax Relief Committee tell a different story. The decision was made at an executive meeting that ended at 1:30 a.m. on Saturday—before the Americans arrived: “Bellevue has been vacated by the military authorities and … would be available for an emergency hospital, and it was decided that such emergency hospital should be taken in charge by the Boston contingent of the American Red Cross.”

Like other buildings in Halifax, Bellevue was damaged. Ratshesky says it was in bad condition, “not a door or window remaining whole, and water and ice on the floor of every room.” He describes how it was refurbished:

By 12.30 o’clock on the first day of our arrival, Major Giddings with his quartermasters, ably assisted by about fifty of the crew of the United States training ship Old Colony, who had arrived with an officer in charge with orders to report to me for service in any way required, together with a company of Canadian soldiers, ordered by General Benson, immediately set to work, cleaning the rooms, covering the windows with paper and boards, as best they could, washing floors and woodwork, and removing all furniture to the upper part of the building.

In his reports to Ottawa, Lieutenant-Colonel Bell was generous with his praise of the Americans, especially of the unit that stayed the longest:

Too much can not be said in praise of the American doctors, nurses and social helpers. Their work was excellent, their spirit willing, and their assistance generous and invaluable. Some of the best surgeons in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Maine were represented, while every U.S. Unit did splendid work. Special mention must be made of the American Red Cross Unit from Boston under the very capable leadership of Dr. W.E. Ladd. The unit was fully equipped and remained in Halifax, doing excellent work until 5 January 1918.

Bell was not impressed with Ratshesky’s description of what happened at Bellevue, as he made clear in a report to Ottawa:

Much has been published in local as well as US papers about this accomplishment and in practically every instance it has been pointed out as a mark of American efficiency. It is only fair to the Engineers, Army Medical Corps and Ordnance Corps to state emphatically that this work, except for assistance in cleaning the building and handling cases of goods, beds, etc., was entirely done by the local units. Captain H. Baret and Sergeant-Major Ansty deserve the greatest credit for this rapid and well-organized work.

Bell added that while the Americans were well equipped, they did not bring any orderlies with them. Canadians recruited from the training depot did that job. Ratshesky’s version of what happened appeared immediately in the Boston press. Bell’s remained in confidential government files for more than half a century. The legend became part of the public record. The reality was never reported. It is not surprising the legend survived.

Lieutenant-Colonel Bell was not the only one who was put off by this American tendency to brag. One local newspaper was so taken with the Americans that it forgot the initial medical response was by local physicians: “notwithstanding that they were called upon to treat their regular patients also helped materially with the wounded.” The Halifax Medical Society reviewed that report at one of its meetings and decided a formal reply was called for. Quoting the offending article, the society wrote:

Some of the medical men of this city have resented this manner of describing the part they played in the surgery arising out of the explosion. The fact is that they and certain colleagues from outside Halifax bore the whole burden of surgical relief until the various hospital units from the United States were installed in their respective buildings. The Massachusetts State Guard was the first American unit to arrive, namely on December 8th, on which day it entered work at Bellevue. Three other units did not take over hospital duties until December 9th. One American unit (Rhode Island) arrived on December 10th and took over hospital duties on December 12th.

The Canadian doctors could have added that they carried on the bulk of the medical response even after the Americans arrived.

AMERICAN HOSPITALS

Despite these reactions, the American legend persisted because the real problems with the emergency hospital situation were never discussed. They are not evident in a casual reading of the records and came to light only fifty years later, when John Crerar MacKeen, the Royal Military College cadet, published an account of his experiences. On the day of the explosion, as we have seen, he had helped recover the wounded, and would later serve as a volunteer in the military patrol of the devastated area; but, on 7 to 10 December, he was at Camp Hill, changing dressings until “his fingers were infected.”

MacKeen’s account describes a medical crisis at the hospital. Halifax physicians who performed the initial surgery, and the physicians from Truro, Kentville, Wolfville, Windsor, New Glasgow, Amherst, Sackville, and Moncton who backed them up, worked without relief for four days. By the time Captain Frederick Tooke arrived from Montreal on Monday morning, one physician had operated sixty hours non-stop. He and others like him were exhausted. Given American physicians had been arriving in Halifax since Saturday morning, MacKeen’s story seems hard to accept, but he was absolutely right. The first physicians to arrive—the ones from Truro, Kentville, Wolfville, Windsor, New Glasgow, Amherst, Sackville, and Moncton—had gone where they were asked to go. The Americans were not prepared to do that. Except for a few physicians who came alone or in small groups from towns in nearby Maine, the American doctors insisted on working as teams. That means they, not the Canadians who were supposedly running the show, decided how their services would be used.

When the first group from Boston arrived Saturday, instead of being sent to the overcrowded existing hospitals—where exhausted Canadian physicians had already worked for thirty-six to forty-eight hours—the Americans took time out for lunch with the prime minister, then went to their billets. Abraham Ratshesky told Lieutenant-Colonel Bell that the Americans should work as a group, “my opinion being that the greatest good could be done in keeping the unit working together and establishing a hospital at the first possible moment.” He was correct that mixing medical staff from different communities and different hospitals could lead to problems, as they all had their own protocols.

However, the decision to keep the Americans together as groups also had serious negative effects. The number of physicians and nurses assigned to each new hospital was based not on the size of the hospital or the number of beds it had, but on the number of physicians and nurses from a particular US location. Thus, although Bellevue, Halifax Ladies’ College, the YMCA, and St. Mary’s had roughly the same number of beds, they had a very different number of doctors. The Ladies’ College and St. Mary’s had one physician for every six beds, Bellevue one for every twelve, the YMCA one for every thirteen. The nursing staff was also unevenly divided. St. Mary’s had one nurse for every two beds, Bellevue, one for every three. However, the Ladies’ College had one American nurse for every twenty beds, the YMCA the same. Both had to back up their American nurses with Canadian volunteers.

That was only part of the story. The decision to send the Americans to their own locations meant that the existing hospitals—the Victoria General, Camp Hill, Cogswell Street, and the Infectious Diseases Hospital in Dartmouth—were staffed entirely by the exhausted Canadians. Yet these hospitals also had the most seriously injured patients. That was partly because buildings such as the YMCA were filled by those with comparatively minor injuries, and partly because the most serious cases could not be moved. The patients desperately in need of skilled medical help were left in the existing hospitals and cared for by Canadian physicians, many of them general practitioners. In other words, while the Americans created their new hospitals for the least injured survivors, the Canadians kept treating the ones with the most serious injuries. There were a few exceptions to this pattern. A Massachusetts eye surgeon saw an American named Bertha Ferguson even though she remained at Camp Hill. The physician came over because of a personal request that came from Massachusetts’ lieutenant governor, Calvin Coolidge, later president of the United States.

When Lieutenant-Colonel Bell’s daily reports were passed around Militia Headquarters in Ottawa, senior officers scribbled marginal notes about the nurse–patient ratio. On 21 December, the Surgeon General informed Bell: “The ratio of nurses employed on the 16th of December seems very high. A total of 319 to serve a total of 1,314 beds, of which 796 were occupied, means a nurse to every three patients.” Bell replied rather feebly that the highest ratio was at St. Mary’s and that the American Red Cross was paying for these nurses. He added the ingenious explanation: “The fact that these nurses are very much cut up with many small rooms and difficult stairways necessitates the employment of a larger number of nurses that would be used in an ordinary hospital.” That was far from the truth. The real reason why there were so many nurses was that the American insistence on remaining in groups had led to an uneven standard of medical care, from nurses as well as doctors. The Americans insisted on working in units no matter how many of them there were and how many patients needed treatment.

AMERICAN COMPLAINTS

The Americans had some concerns, too, though they, like the Canadians, kept quiet—at least while in Halifax. The first complaint came from the medical staffs of Tacoma and Von Steuben. When they arrived Thursday afternoon, they offered their services at local hospitals. According to them, they were rebuffed. Captain Powers Symington of the Tacoma commented: “Conditions were abnormal and no adverse criticism is intended but looking back with the light of this experience it is clear that relief efforts were not as productive of beneficial results as they might have been.” The complaint is a bit surprising. Dr. Petterson from Old Colony went to Camp Hill immediately after the explosion and was put to work for the rest of the day. The physicians from Tacoma took over on board Old Colony, assisted by Canadian nurses.

The second complaint was more serious and became public when the Americans returned home. Although the physicians from Providence told Lieutenant-Colonel Bell that the medical canvass (which they had done reluctantly) did not suggest problems in Halifax, they told the Providence newspaper a different story. Dr. Frank Adams said that the canvass turned up hundreds of injured people, “and also those in need of food, fuel, clothing and money.” In fact, he said, the first day, the Rhode Island physicians treated 163 people in their homes, including three who had still not seen their family doctors and found twenty-three families who needed food, clothing, or shelter. There was some truth to that. A report by Bell’s nursing director, Grace O’Bryan, said calls were made on 3330 homes. Of these, 211 were empty and 297 got no response. About 60 per cent of the rest had no one injured. But the nurses treated 987 people, found 7 who needed immediate treatment, 15 who had to be referred to a physician, 8 who required a nurse, 73 who needed to be sent to a dressing station, 32 who had to be referred to the Rehabilitation Committee, and 11 who needed assistance from the Victorian Order of Nurses. That totals 146, close to the figure used by the physicians from Rhode Island when they returned home.

SOCIAL WELFARE

The real problems, however, were not with medicine but with social welfare. Here the conflicts were more open. A history of the American Red Cross, written in 1950, noted “serious tension” between the Americans and Canadians in Halifax: “The failure of the Americans to recognize the delicacy of a task which involved their directing the expenditure of funds largely contributed by Canadians was a gross error in tactics. If the tables had been reversed and the Bostonians had had to take orders from the natives of Halifax, the resulting furor would have been terrific.”

Those concerns might have led to publicized conflicts, but one influential lawyer in Halifax was noting those tensions and quietly passing reports to Henry Endicott, the head of the Massachusetts relief effort in Boston. His name was G. Fred Pearson and he is the man who deserves the credit for the legend about the American response.

Because of Pearson’s confidential reports, Endicott, the man with overall responsibility for raising funds for Halifax, decided to pay a personal visit to Canada. He brought with him the vice-chairman of the Massachusetts–Halifax Relief Committee, James J. Phelan, and its treasurer, Robert Windsor. He also brought along Abraham Ratshesky. Endicott held a lengthy meeting with the Halifax Relief Committee and discussed a future role for Massachusetts in Halifax. He did not say so, but that meeting reflected his growing concern that things were not going well: “The people who lived in the devastated area have been investigated and investigated until they are sick at the thought of investigation. The investigation in all cases has not been carried out by sympathetic and mature people.”

After that meeting, Endicott decided that Massachusetts should step aside from the existing Halifax relief process and set up its own organization. That new approach was so sensitive and so well run that it did not lead to a single recorded complaint. More than anything else, it led to the legend about the Massachusetts response to Halifax.

GIFTS FROM MASSACHUSETTS

What Fred Pearson had noted was that some homes were being repaired and that others were being rebuilt, and that in both cases the occupants needed furniture. Massachusetts, he suggested, could supply that furniture. However, the same furniture would not go in every house. Massachusetts would set up a warehouse where people could choose what they wanted, and produce a catalogue that people could look through so they could make their personal choices even before they visited the warehouse. Once the choice was made, the goods would be ordered from Massachusetts then sent to the individuals, “packed, tagged and addressed to the person in Halifax.” That would eliminate standardization and it would mean each family would receive its own personal gift from the people of Massachusetts.

This was a brilliant idea and Pearson carried it ever further. He realized that the Halifax Relief Commission15 would want to deduct the value of that furniture from other relief, which would undermine the whole approach. The furniture was to be a gift, not charity. On his advice, the Massachusetts–Halifax Relief Committee took the position that, “the assistance should be offered in the spirit of a gift from a friend to a friend, rather than in the spirit of charity or compensation.” Though it received information from the government, it declined to give the government access to its records. The government argued that if the two organizations did not share information, some people might be better off because of a gift from Massachusetts. As far as Pearson was concerned, that was fine. Despite heavy pressure, he declined to provide information about who was helped. He told the Halifax Relief Commission: “To cooperate with the Commission in the manner asked for and consider the Massachusetts furnishings as relieving the Federal Government would defeat the very object that the Boston Committee had in view.” That was, of course, a dramatic shift from the earlier philosophy of making sure no one benefited from the explosion.

However, Fred Pearson included some safeguards. If the “gift” approach was to work, Massachusetts could not question the victims about their situation and their financial resources. The victims must be invited to the warehouse and given a chance to choose what they wanted, without being the target of an inquisition. Yet, some way had to be found to establish who deserved such help and that had to be done without bothering the victims. Pearson’s solution was to ask prominent women from Halifax–Dartmouth to assist—“ladies who lived in, or near the devastated district and who would know many of the people who had suffered loss or damage and would be in a position to report to this committee on the nature of the loss suffered and recommend the form that a gift should take.”

He even laid out the ground rules for their inquiries: “It is therefore proposed to investigate these cases first endeavouring to get all the information available from the friends or acquaintances of the family, in order to arrive at some independent opinion of their necessities, and finally to visit the family and from the standpoint of a friend, offer them assistance in the fitting out of their new home.”

To make certain the system worked precisely as planned, Massachusetts required its investigators to follow rigid procedures, but insisted that everything be done discreetly. When the persons to receive assistance were finally chosen, then and only then did someone actually visit them—and, since the decision had already been made to provide assistance, that visit did not lead to any questions except What precisely would you like? By doing it that way, Pearson ensured that no one ever found out that he or she had been turned down. The original investigators were Mrs. H.A. Payzant, Mrs. George McKenzie, Mrs. Thomas Stokes, Miss T.R. Sullivan, Miss K. Healey, Miss A. Chisholm, Miss Florence Malcolm, Miss C. Wells, Mrs. Marie Williams, and Miss A.L. Wickwire. Later, Mrs. Flinn joined the team. (Notably missing were the three women from the Halifax Relief Committee and Clara MacIntosh, who ran the original survey. In fact, only one woman involved in the original survey was in the group assisting Massachusetts.)

Although the idea of a catalogue was dropped as too complicated, Endicott endorsed the rest of Pearson’s ideas and the system worked exactly as Pearson suggested. Massachusetts sent its own furniture agent, Nathaniel Littler, to Halifax in February 1918. He acquired rent-free premises and filled these with samples of furniture. People chosen to receive gifts came and made a selection. The furniture they chose was shipped to them from Massachusetts with their name on it. (Items were to be purchased in Halifax only in an emergency.) All in all, Massachusetts refurbished 1831 homes. The gifts included 1606 beds, 1791 blankets, 824 pair buffets, 2420 blinds, 496 sewing machines, 125 baby carriages, 170 cribs, 1978 mattresses, 1978 bedsprings, and 1501 refrigerators.

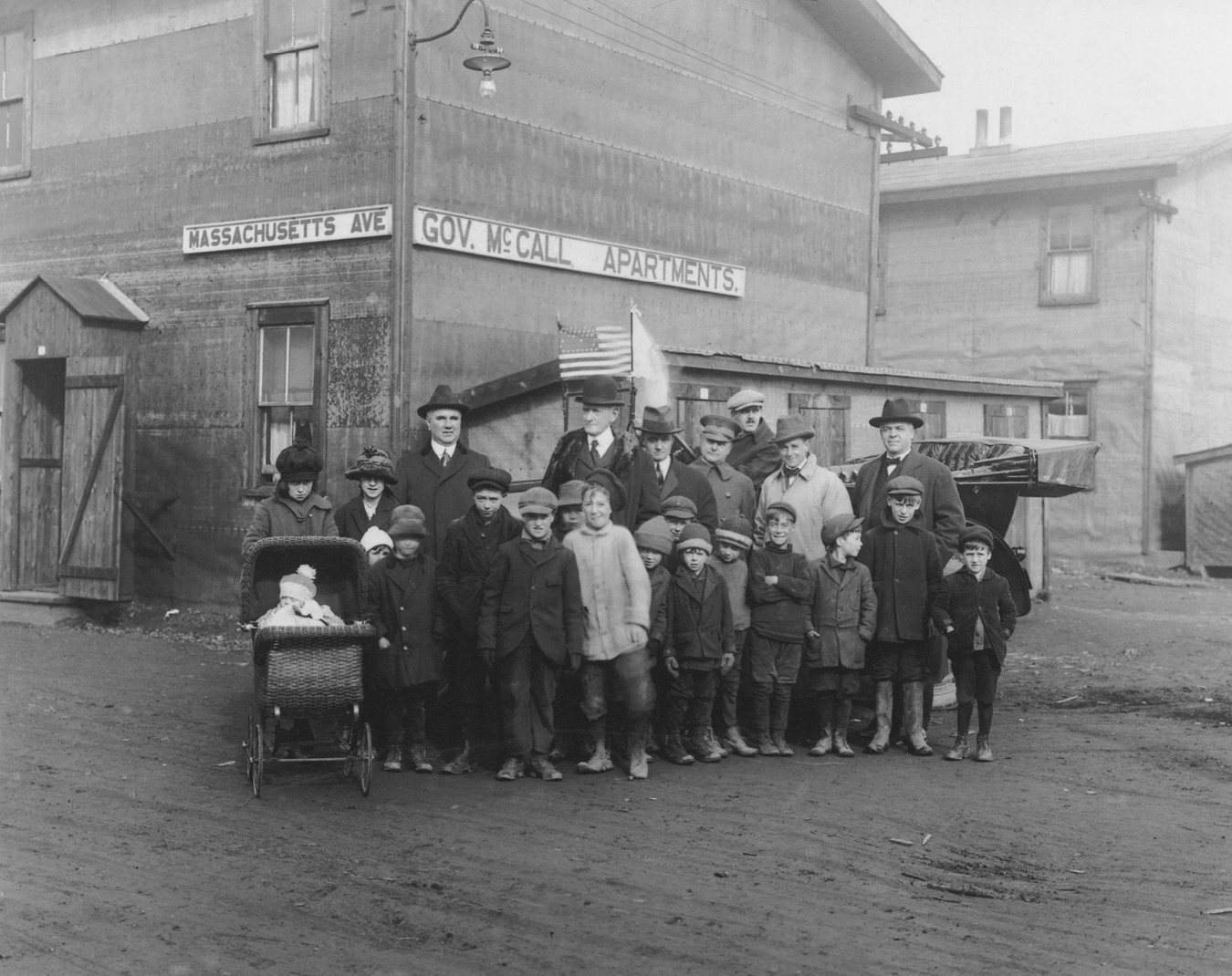

The minutes of the Massachusetts–Halifax Relief Committee leave no doubt that those who received help needed it. One report covered John and Margaret Stokes, their six children, their son-in-law, John Hinch, and two grandchildren. All had lived together at 21 Acadia Street. One of the Stokes children lost an eye, another a leg. Mr. Hinch and his youngest son were killed in the explosion. The family lost its home. The committee gave them four beds, bedsprings, mattresses, sheets and pillowcases, and other bedroom furniture such as bureaus and commodes. The committee also helped refurbish St. Joseph’s Orphanage, the Protestant Orphanage, the Old Men’s Home, St. Joseph’s Home, St. Patrick’s Home, the School for the Deaf and Dumb, the Jost Mission, and the Home of the Guardian Angel. It provided pianos to the Royal Canadian Naval Hospital and St. Joseph’s Convent, and organs to the Children of Mary in St. Joseph’s parish. It also provided playground apparatus for new apartment buildings16 named after Massachusetts Governor Samuel Walker McCall. (Governor McCall eventually visited Halifax and posed for pictures with children enjoying the new playground.)

Despite its rigid procedures, the Massachusetts–Halifax Relief Committee was responsive to suggestions from others. The principal of Acadia, Dr. G.B. Cutten, who had come to Halifax on the first relief train from Kentville the day of the explosion, took leave from Acadia in the summer of 1918 to direct the rehabilitation department of the Halifax Relief Commission, using his background as a psychologist. On his recommendation, the commission provided washing machines, bread mixers, special high chairs, and kitchen cabinets for Mrs. James Hynes, Mrs. Mary Miller, Mrs. James Monamy, Mrs. Elizabeth Bewes, Mrs. Winnifred Brown, Mrs. Victoria Conrad, Mrs. Sarah Heaton, Mrs. Frank Robinson, Mrs. James Foran, and Mrs. D. Hinds. All of these women were living at home but had been blinded by the explosion. (Mrs. Monamy was an especially sad case. She had been pregnant at the time of the explosion and lost her baby as well as her six-year-old son.) The person responsible for the blind program wrote his thanks: “When we first came, practically all the women who had lost their sight in the explosion were sitting in absolute idleness in their homes. It occurred that the best thing we could do for these women was to re-educate them sufficiently to perform their household duties.” The gifts from Massachusetts had allowed that to be done.

FIGURE 14.2 | Massachusetts’ governor Samuel McCall (second from left) briefly visiting namesake temporary apartments, in November 1918, at the Exhibition grounds in Halifax: “Time is of the utmost importance.” Charles Vaughan, a future mayor of Halifax, is in the baby carriage. Nova Scotia Archives. Gavin & Gentzel, 8 November 1918; NSA, Halifax Relief Commission, MG 20 vol. 200 / negative: N-7045.

While it acted discreetly, to make certain others did not damage its goodwill, the committee acted promptly to protect its turf. When the Young Women’s Christian Association tried to raise money in Boston, the committee persuaded it to stop. After a meeting with YWCA leaders, the chair of the Massachusetts–Halifax Relief Committee wrote to say, “I think you understand that the [Halifax Relief] Commission has done everything it possibly could do to discourage the use of the Halifax disaster for money-raising purposes—no matter how praiseworthy that might be.” What really left a good impression was the willingness of the committee to deal with individual problems. It provided a piano for Evelyn Moseley, who supported herself and her mother by teaching music and had lost her piano in the explosion. It provided tools for Alfred Fougere, fifteen, who had patiently saved his money to buy shoemaking tools so he could apprentice as a shoemaker but then lost those tools in the explosion. It refurbished the homes of clergy. It provided help for churches.

The thank-you letters poured in. William Swetnam, the minister who lost his wife and son, wrote from his new home in the Methodist parsonage in Bridgewater to say how much he appreciated their kindness, “a kindness that will never be forgotten by me and my motherless girl.” (Swetnam’s wife had been playing the piano when she died and that piano was destroyed. The relief commission had declined to replace it.) V.R. Purcell painstakingly typed his thanks on his new typewriter: “This typewriter furnishes me with the missing link which connects me to the outside world from which I was so suddenly cut off on the morning of December 6th…. I had the misfortune to lose both my eyes.” Sydney King, the pastor of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, also sent his thanks. Massachusetts provided $150 for a small organ for his church.

Massachusetts estimated that its gifts would cost $500,000. That turned out to be far too high a figure, partly because the committee managed to buy all its supplies wholesale and partly because all its gifts came in duty free. That left the state with several hundred thousand dollars. It spent much of that money on long-term health care, especially in an effort to deal with and eliminate tuberculosis.