CHAPTER XVI

MEDIA DISTORTIONS

THE EXPLOSION KILLED JACK RONAYNE, A TWENTY-THREE-YEAR-old reporter covering the fire for the Morning Chronicle and its sister paper, the Daily Echo—the only journalist who died in the disaster. The blast damaged the printing capacity of local newspapers and knocked out all long-distance telephone and telegraph lines. As a result, the local newspapers could not publish accounts of what happened. That helps explain why the initial reports of the explosion came from the small towns of Amherst and Truro, Nova Scotia, the railway centres closest to the city, and why the first bulletin from Halifax by a local journalist, James Hickey, came some three hours after the explosion by way of ocean cable through Havana, Cuba. These early bulletins, and then a full account Hickey was able to dispatch on the evening of 6 December, when telegraph service began to be restored, were the basis for much of the initial national and international coverage. Not surprisingly these early reports emphasized the devastating destruction. This was especially so in Hickey’s long account, which was widely reprinted. Hickey, working in the midst of chaos only a few kilometres from the North End, had no way of knowing about the spontaneous response of individuals, local authorities, and the railways in other parts of the city and across the province. There was information about local relief efforts in the bulletins from Amherst and Truro, the towns that rushed through the first outside help, but these did not have the impact of Hickey’s dramatic coverage. Soon the Halifax newspapers were back in business, other reporters arrived in the city, and the stories of the immediate response to the disaster were not written.

The distorted reporting did not stop there. The trains from Boston and New York carried journalists who filed stories as their trains worked their way through the blizzard. Since the telegraph lines were open along the route, and since they had senior officials of the railways with them, those stories were moved to their newspapers and passed to other media. Those stories dealt with the American response—which had yet to reach Halifax—rather than the Canadian activity in Halifax. In other words, the absence of Canadian content created a vacuum and the Americans filled it. To those who study the media, it is a familiar story: Canadians tend to see the world through US eyes. (That same perspective explains why the sinking of Titanic—carrying many prominent Americans—got so much more attention than that of the Empress of Ireland—with mainly Canadian passengers.)

Once the Americans did arrive, they wrote stories on what the Americans were doing: refurbishing buildings and turning them into hospitals, taking care of injured survivors, and shipping trains and boatloads of supplies to the stricken city. Those stories made their way to New York, the major North American media centre. They were the stories that flowed round the world. Even the supposedly reputable London Times built its inaccurate version of what happened from reports in the American press. When the Americans left, world media coverage dwindled. While some stories still came out of Halifax, the attention shifted to events in Jerusalem, St. Petersburg, Moscow, and the European trenches. Even in Halifax, news about the explosion faded as attention turned to the upcoming election.

The initial news bulletins broke from Amherst, a Nova Scotia town close to the New Brunswick border. Amherst was on the Intercolonial Railway and the railway telegraph messages from Halifax, relayed from Rockingham to Moncton via Truro, could be heard by the station operator there. Someone connected with the newspaper either understood American Land Line code and heard what was passing through on the railway telegraph, or talked to someone else who had. About twenty-one minutes after Mont-Blanc blew up, the paper sent the following brief message to the Canadian Press: “09:26 a.m. (Amherst) American ammunition boat collided with another boat at Rockingham, three miles from Halifax. A section of Halifax is on fire.” This report was wrong about the location of the explosion and wrong in stating that the ship was American. The incorrect location came because the listener mistook the place where the message was being sent for the place where the explosion occurred. However, it got two essential elements right: a ship carrying munitions had been involved in a collision and part of Halifax was on fire. Amherst put out that bulletin for two reasons. First, the telegraph and telephone lines to Halifax were down. (That had also happened the previous Sunday, when a major sleet storm hit the Maritimes, though the weather on 6 December was cool and clear.) Second, and more important, the people of Amherst, like the people in most of Nova Scotia, had felt the shock of the explosion. Given Coleman’s message, the downed telegraph and telephone lines, and the shock that everyone had felt, something had to be seriously wrong. It made sense that the munitions “boat” mentioned in the overheard message was that something.

The Canadian Press, today widely known as CP, the Toronto-based co-operative national news agency that had been established only a few months earlier and had yet to break a big story, placed a long-distance phone call via Amherst to the Truro Daily News, a member of the association. The man who answered was the publisher, A.R. Coffin. Born in Port Clyde in Shelburne County, Nova Scotia, Alfred Rickert Coffin attended Mount Allison and then, in 1894, when he was nineteen years old, joined the Daily News as a reporter for $5 a week. By the time of the explosion, he had twenty-three years of newspaper experience. He had also saved his money and purchased a one-sixth ownership of the News. Coffin was in charge and free to make whatever decision he thought wise. He, too, had felt the shock of the explosion, but the first message about it had yet to arrive, so there were no plans yet in Truro to send a relief train. Coffin decided to cover the story himself and to do so by going to Halifax by car. He called a taxi and he, the driver, and a mechanic—the driver was taking no chances—set out for Halifax.

Today it is possible to drive the ninety-six kilometres from Truro to Halifax in roughly an hour. There’s a four-lane highway most of the way. In 1917, it took Coffin three times as long. In a letter to M.E. Nichols, quoted in (CP) The Story of the Canadian Press, Coffin wrote: “Roads were in the worst possible condition, having been gutted badly before freezing and in places covered with ice and snow. In spite of the roads, we made the trip in three hours. You would know that in the lightly loaded car we did not spend much time on the seat.”

While Coffin was en route, news reports continued to trickle out. At first, stories on both CP and AP (Associated Press, CP’s American equivalent) reported only that Halifax was cut off. When they did refer to an explosion, they vastly underestimated what happened and they got some details wrong:

- 09:50 a.m. (CP from Montreal) Reports reaching telegraph companies here indicate that the explosion near Halifax has affected their dynamos. All wire communication with Halifax and outside points severed.

- 10:03 a.m. (CP from Montreal) According to reports reaching here a number of people were killed when the explosion occurred in Halifax this morning.

- 10:13 a.m. (AP from Boston) The Postal Telegraph Company’s lines were down. The local office stated that Montreal reported no wires working east of the city. One report was that an explosion of a bomb killing a number of men occurred at 9:30 o’clock.

- 10:20 a.m. (CP from Saint John) It is announced here that the censor at Halifax has taken control of all wires in connection with the explosion there this morning.

- 10:27 a. m. (AP from New York) Halifax has been cut off from all communication with the rest of the world either by wire or cable according to the officials of the Western Union Cable Company in this city. All land wires are down and the plant of the United States Cable Company at Halifax has been so damaged by the explosion that it can not be operated.

It was about then—nearly ninety minutes after the explosion—that W.A. Duff of the Intercolonial Railway reached Rockingham. His message went from Rockingham to Truro and then from Truro to Moncton. Once again, someone in Amherst was listening. This time the listener was sure there had been a serious explosion: “10:35 a.m. (CP from Amherst) Hundreds of buildings were destroyed or damaged, scores of lives believed lost, and certain sections of the city are in flames.” Even then, however, the full extent of the damage was not getting through:

- 10:37 a.m. (CP from Ottawa) According to advices received here the Halifax disaster was due to the blowing up of munitions ship in the harbour at eight o’clock this morning. [That is a reference to Ottawa time.] All telegraph lines are down and the damage is very serious. It is believed a number of people near the scene were either killed or injured, including several telegraph employees.

- 10:40 a.m. (AP from Boston) Efforts to communicate by wireless with Halifax were being made. There was some difficulty, however, because of the war regulations under which radio stations on the Atlantic coast are now operated. None of the radio stations have received anything concerning the explosion up to 10:30.

- 12:05 p.m. (CP from Truro) It is reported here that the first estimated loss of life in the explosion in Halifax harbor this morning places it at fifty, while the number injured is correspondingly great.

Truro was now starting to hear more news of what was happening through the station operator as more messages were relayed to Moncton. It was only at 12:26 p.m., three hours and twenty-one minutes after the explosion, that a message originating in Halifax came from Havana, relayed by AP in New York to Toronto, finally indicated the seriousness of what happened: “Hundreds of people were killed and a thousand others injured and half the city of Halifax is in ruins as the result of the explosion on a munitions ship in the harbour today. It is estimated the property loss will run into the millions. The north end of the city is in flames.”

This bulletin came from journalist James Hickey. He had been born in Halifax in 1869, joined the city’s Chronicle-Herald in 1883 as an office boy, and had risen through the ranks to become the news editor; he was also a correspondent for the New York Times and “superintendent of the Eastern Division” of the new Canadian Press. A resourceful and determined newsman, he had achieved a scoop in reports on the survivors of the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. On the morning of the explosion he had been in his office in the downtown of the south end of the city, and was showered by glass from the building’s shattered windows but not seriously hurt. After making his way toward the North End through the crowds of people, many injured, heading south, he returned to the telegraph offices in the downtown and ran into John A. Hagen, the manager of the Halifax and Bermuda Cable Company, which, despite the fact its office had been reduced to a shambles, proved to be the only communications connection that had not been broken. Hagen banged out the bulletin that Hickey dictated for transmission to New York on the Associated Press service. The Halifax–Bermuda service connected to a cable to Jamaica, thence to Havana, which linked into the US cable system and explains the Havana address on the Associated Press story.

Later, on the evening of 6 December, Hickey filed a full story of some 1200 words for CP that correctly estimated the death toll at 2000 and said it was a French ship that exploded.

HALIFAX, Dec. 6—As a result of a terrible explosion aboard a munitions ship in Halifax harbor this morning, a large part of the north end of the city and along the waterfront is in ruins and the loss of life is appalling.

Estimates place the number of dead at over 2,000. On one ship alone, 40 persons were killed. Thousands have been injured. The property damage is enormous and there is scarcely a window left in a building in the city.

Among the dead are the fire chief and his deputy. They were hurled to death when a fire engine exploded. Fire followed the explosion and this added to the greatest catastrophe in the history of the city.

All business has been suspended and armed guards of soldiers and sailors are patrolling the streets.

Not a streetcar is moving and part of the city is in darkness. All the hospitals and many private houses are filled with injured.

The offices of the railway station, arena rink, military gymnasium, sugar refinery and elevator collapsed and injured scores of people.

The munitions ship was bound from New York for Bedford Basin when she collided with a Belgian relief ship bound for the sea.

That story made headlines around the world. After hours of speculation, it was clear there was a catastrophe. Hickey’s only important error was the suggestion that the fire engine exploded. In fact, it was engulfed in the explosion of Mont-Blanc. He was correct about IMO being involved in Belgian relief, but—though he did not say so—that left the impression she was a Belgian ship, a misunderstanding that persisted in many of the reports that followed and occurs in accounts of the explosion even today. (An issue of the Canadian magazine Maclean’s repeated the error.) In the next paragraph, however, Hickey described something that never happened:

Five minutes after the explosion occurred the streets were filled with a terror-stricken mob of people, each one trying to make his way as best he might to the outskirts in order to be out of the range of what they thought was a German attack.

Women rushed in terror stricken mobs through the streets, many of them with children clasped to their breasts. In their eyes was a look of terror as they struggled in mobs through the streets with bloodstained faces.

Unlike his estimate of 2000 dead—which came from the chief of police—Hickey cites no source about the panic, and it appears to be his own eyewitness account. As we now know, there was a substantial evacuation of the North End, though those who fled were not a “mob.” Furthermore, the flight was not out of fear of another German attack but because police and military personnel told people to leave because there was danger of an explosion at the Wellington Barracks magazine. In any case, the evacuation was not a panic-stricken reaction five minutes after the explosion, but an orderly one about an hour after Mont-Blanc blew up.

Hickey was running into a problem that faces all reporters trying to cover disasters. They think that victims are dazed and confused and that there is panic and looting. They think organizations know what happened and are reliable sources of information. They are, of course, wrong on both counts. As we now know, individuals behave very well in disasters. It is organizations that have the problems. More significantly, no one—no individual, no one in authority—knows what really happens in the early stages of a disaster response. Even organized activity—such as the rescue work in Dartmouth by sailors from Highflyer, the fire fighting in the North End by the surviving members of the fire department, or the assistance given the injured by passengers from the Boston Express—is done in isolation. Each group does what it can, unaware what others are doing.

There was coverage of the local response, but in the Truro Daily News, whose staff was in touch with the railway officials who organized the early evacuation of wounded to Truro and the dispatch of the first relief trains carrying firefighters and medical personnel from that town. As each morsel of information arrived, the railway staff passed it to the newspaper and the newspaper staff posted it on bulletin boards outside their office. The Daily News posted its first bulletin at 10 a.m., fifty-five minutes after the explosion. It was a succinct account that made no effort to tell anything more than was known: “MUNITION SHIP BLOWN UP IN HALIFAX … The city is covered with smoke; all telegraph and phone wires wrecked; motor cars are rushing to the city from outside points for information and to furnish aid if needed.” (The motor cars included the one in which Coffin was riding.) Soon this was followed by second bulletin:

C.G.R. at Moncton thru Mr. Hayes gathering up all surgical instruments possible and sending Doctors and Nurses.

Amherst will send help at once.

Special [train] just left Truro with Doctors, nurses, 59 firemen and workmen.

Within minutes, crowds were watching each new bulletin. Nova Scotia is a small, tightly knit province and many in Truro had family in Halifax, including children in school. In fact, one of the dead was Arthur Carroll, who had gone to Halifax on business that morning. Before the paper went to press, there was more news from the railway and the Daily News got it in its evening edition:

Halifax Stricken With

Terrible Disaster At

9 o’clock This Morning

Munitions ship in collision at

Pier 6—Ship Set on Fire

A Fearful Explosion in 20 Minutes

Fuller accounts came out in a special morning edition on 7 December, with updated stories in the evening edition. Two of the main pieces were written by the News’s publisher, Alfred Coffin, after his run into Halifax by automobile.

By the time Coffin reached Halifax on the afternoon of 6 December, the original purpose of his trip, to supply copy to CP, had been overtaken by James Hickey’s success. Presumably Coffin learned of Hickey’s efforts, for Coffin visited the various newspaper offices in Halifax offering help in getting them back into production, although none took up his offer to have printing done at his plant in Truro. Coffin and his party left the city at 11 p.m., the car crowded with survivors, and did not reach Truro until 2 a.m. on 7 December. He then appears to have spent the night producing the lead story for the morning edition of the News. His account paints a different picture from the chaos Hickey described in his powerful prose.

Coffin’s report was influenced by his awareness of the relief efforts being mobilized in the towns along the rail lines to the north of the city, and also by the fact he did not arrive until early afternoon. This was some hours after the exodus from the North End following the false alert about the danger of a second explosion, and after the large detachments of troops from McNabs Island and York Redoubt had reinforced the parties of soldiers and naval seamen who were first on the scene. “The greatest good sent to the poor North Enders was the detailing of all soldiers and mariners in companies to assist,” Coffin wrote. He naturally highlighted the early relief parties from north-central Nova Scotia: “A very large delegation of voluntary workers poured into Halifax chiefly from Truro, Windsor, Amherst and the New Glasgow towns and well for the sufferers was it so.” These volunteers and the sailors and troops galvanized the dazed survivors:

Rescuing Dead and Injured

The willing crowds proceeded systematically…. All workers went about rescue work, and as the dead were recovered they were piled in rows on the street sides to be called for by teams. The injured were conveyed to hospitals on stretchers and in every conceivable way.

Neither of Coffin’s long stories appears to have been republished; evidently, they were scooped by Hickey’s more dramatic and timely accounts. Still, according to the histories of Canadian Press, ninety per cent of the Associated Press’s first-day coverage of the explosion in US newspapers was material from CP. The coverage presumably included, in addition to Hickey’s blockbuster stories, the short bulletins from Truro and Amherst that were also widely republished. Coffin received a vote of thanks from the Canadian Press directors, who were impressed by his selfless efforts at a time when the new service was having difficulty winning co-operation from local newspapers.

WORLDWIDE COVERAGE

Although Hickey’s stories appeared everywhere, local newspapers added their own imaginative flourishes. In Toronto, the Mail and Empire told it this way: “EXPLOSION TURNS HALIFAX INTO A SHAMBLES.” Its rival, the Toronto Daily Star, said much the same: “HALIFAX CITY IS WRECKED.” In New York, the Times went into far more detail:

MUNITION SHIP BLOWS UP IN HALIFAX HARBOR, MAY BE 2,000 DEAD;

COLLISION WITH BELGIAN RELIEF VESSEL CAUSES THE DISASTER;

TWO SQUARE MILES OF CITY WRECKED; MANY BURIED IN RUINS

In Paris, Figaro summed it up in four words: “TERRIBLE EXPLOSION A HALIFAX.” One of the few papers without such a headline was The Times of London. As was its custom, it ran the news inside, keeping the front page for commercial announcements.

Frustrated by their inability to get through by phone or telegraph, other newspapers were sending staff to Halifax by train. The Ottawa Journal sent Grattan O’Leary, the Toronto Daily Star, Stanley K. Smith, who later wrote an instant book on the explosion, Heart Throbs of the Halifax Horror. The Boston papers sent reporters, as did the Associated Press. Others came from New York. All found themselves caught in the blizzard that struck the day after the explosion. The Fredericton Gleaner reported on Friday that newspapermen on the relief train that passed through Saint John Thursday night were still stalled in snow. “This,” the Gleaner reported, “explains why more news of the incident has not been received.”

The first reporter to reach Halifax after Coffin was Stanley K. Smith. He was city editor of the Saint John Daily Telegraph and the Toronto Daily Star’s correspondent for the Maritimes. His train arrived Friday, the first to go to the south end of the city. Although the tracks were open, there was still no station in the south end. When Smith got off the train he found himself with no transportation, alone in a raging blizzard. He had to walk more than three kilometres before he found a hotel that offered to let him share a suite, provided he could fix it up. He tracked down a man who ran an all-night restaurant and, from him, borrowed a hammer and nails and went back to the hotel and nailed mats across the windows. He moved the piano aside and made up a bed on a mattress on the floor. He then headed out to do some reporting. When he approached the telegraph offices, he was told at first that no wire space was available. Eventually he was promised he could file a few short items. He tried to keep his copy as short as possible and learned later that everything he filed that night got through. However, when he returned to his hotel, his room and mattress had been taken over by a soldier.

LOCAL COVERAGE

By then, the Halifax papers had started to report the news themselves. The Herald was a morning newspaper and its Thursday edition had been off the press before the explosion occurred. The Halifax Mail was still on deadline, but its office was a shambles. The windows were shattered, the partitions in the offices and composing room were down, and the press was filled with shattered glass. There was no power and no gas—the fuel used to heat the type. On Friday, however, the Herald got out a one-page special (the editor called friends, including a local physician who knew how to set type by hand) and provided a reasonably accurate account of what happened:

HALIFAX WRECKED

More Than One Thousand Killed in This City,

Many Thousands Are Injured and Homeless

At 9.05 o’clock yesterday morning a terrific explosion wrecked Halifax killing over a thousand, wounding at least five thousand, and laying in ruins at least one-fifth of the city.

The Belgian relief steamer Imo coming down out of the Basin in charge of Pilot William Hayes collided with the French steamship Mont Blanc in charge of Pilot Frank MacKay. The French steamer was loaded with nitro glycerine and trinitroluol. Fire broke out on the Mont Blanc and she was headed for Pier 8. It was eighteen minutes after the collision when the explosion occurred. The old sugar refinery, and all the buildings for a great distance collapsed. Tug boats and steamers were engulfed and then a great wave rushed over Campbell road carrying up debris and corpses of hundreds of men who were at work on the piers and the steamers.

Without the loss of a moment hundreds of survivors rushed to the rescue of those buried in the ruins. Fire broke out in scores of places and soon the great mass of wreckage was in the grip of an uncontrollable fire checking the work of rescue.

The Herald said it was sending the one-page hand-printed bulletin to every town “in order that as many as possible may know at least some of the details of the disaster.” It asked its readers for patience. The Herald suffered only explosion damage. The Halifax Chronicle suffered not only explosion, but also fire damage. When Stanley K. Smith visited its office Friday morning, he found the lobby full of water. Smith said, “The composing room seemed a wreck but work was going on and I was told one linotype was working.” (A linotype is a machine that sets type, one line at a time.) One local paper did get out the news on the day of the explosion. The Dutch ship Nieuw Amsterdam kept its 300 passengers informed with a daily news sheet. The morning of the explosion, it told its passengers—who had felt the shock of the blast and seen the cloud rising above the city—that an ammunition factory had exploded.

When the Halifax papers did start publishing, they used enormous headlines—on Saturday, for example, the Herald’s front page looked like this:

YET MORE APPALLING

The Death Roll Still Grows and the Tremendous

Property Loss Is Beginning to be Realized

However, they failed to catch up on what they had missed. Their coverage ignored the critical role played by the railways, the contribution made by the physicians from nearby Nova Scotia and from New Brunswick, and the fact much of the initial search and rescue and initial first aid was done by the survivors themselves. The local papers did, however, play another important role. For weeks after the explosion, they carried advertisements for people trying to locate lost family members. On 4 January, for example, the Acadian Recorder carried the following notices:

- Mrs. Maurice Shea, age 48, and daughter, Ernestine, age 5 … last seen in the field near Hillis’s foundry. Two naval men came to their assistance and took them away.

- Mrs. Charles Vaughan … was rescued by Mr. Vaughan and taken from there by ambulance. Will the ambulance driver who took this patient away kindly communicate with Mrs. Snow …?

- Frank Bell, aged 3, son of Thomas Bell … last seen taken from ruins by sailors.

- Roy De Wolfe, age 6 years … missing from Protestant Orphanage … reported to have been taken away by a soldier and a sailor in an automobile.

MAKING IT UP

Because they were unable to reach Halifax, reporters for other media were doing their best to find their own angles on the story. They interviewed shipping agents, local residents who had been to or came from Halifax, and local businesses who had connections there. They carried stories about relief efforts from their own communities. They carried the minimal information available from dispatches from Captain Powers Symington of the US warship Tacoma (which had felt the explosion), made public by the US Navy in Washington, and the report sent by Major-General Thomas Benson, made public by the militia department in Ottawa. In Toronto, they pressured the minister of Railways, J.D. Reid, for information and he released the telegrams he had received from Halifax and Moncton.

As for the reporters en route, the best they could do was talk to each other or try to grab interviews with travellers going the other direction. As a result, much initial coverage of the explosion was ludicrous or fictional. One story out of Saint John said that, “at the moment of the explosion, a fierce storm was sweeping the harbour.” It was actually a cool, clear day with no noticeable wind: the “storm” was creative imagination. That error was reported in The Times of London, which, in its first brief summary, announced: “Halifax, the great Canadian port on the coast of Nova Scotia, has been wrecked by the explosion of a munitions ship. During a gale, the munitions ship, coming out of harbour, came into collision with another steamer and was set on fire. There has been great loss of life.” The Times would have been wiser to stick to a report filed by the commercial news service of Lloyd’s of London. Its account, filed the day of the explosion, was generally accurate: “A steamer loaded with munitions exploded in harbour after collision with steamer Imo and is a total loss. Crew safe. The Imo is very seriously damaged and beached. Crew all missing. Loss of life and property ashore very serious.” Most of IMO’s crew was alive, but since Lloyd’s did not know that, unlike many other news services, it did not speculate.

There were probably two reasons why reporters who could not make it to Halifax used their imaginations. One was that the people they interviewed had not seen very much. The Boston Express, for example, had stopped short of the North End station and then turned around. The passengers on that train had seen the damage in Africville and the fires in the distance, but they had no idea of the cause. The students heading home to Boston from Mount St. Vincent Academy had been even farther away: they had felt the explosion and helped the injured who fled from the city, but they knew little else. Both groups of passengers were willing to talk to reporters, but there was not much they could tell them about what happened. The other problem was that those who had been in Halifax had little to say. Helen Havener of the Portland News said that was because reporters in other cities had already besieged them. In fact, those who had seen the horror did not want to talk about it. Like soldiers coming home from a war, they wanted to put it behind them.

Some accounts were at least partly accurate. The New York Times seems to have figured out how the collision occurred:

The munition ship, bound in from New York, had almost passed through the narrows leading from the outer harbor into Bedford Basin to the northwest, when the collision occurred. The Imo, westward bound, was just putting to sea.

The weather was clear and the two ships had room in which to pass. Because of a misunderstanding of signals, however, they headed for each other. Their efforts to avoid each other were unsuccessful and the Mont Blanc was pierced on the port side.

That was close to the truth except that the damage was to Mont-Blanc’s starboard side. However, the Times story went on to quote IMO’s pilot as saying that “soon after the collision, burning oil spread fiercely over the fore part of the ship.” Since IMO’s pilot was killed in the explosion, that was an impressive bit of reporting. The story added that following the collision IMO “caught fire and seemed for a time in imminent danger of destruction. Accordingly, she was beached.” IMO, of course, did not catch fire and she was not beached. She was driven into the Dartmouth shore by the force of the explosion.

Not to be outdone, the Boston press reported on its front page a story in which A.S. Goldberg stated that the explosion had occurred when a naval magazine blew up, setting ships adrift, and that some of those ships had collided with a munitions ship, causing the explosion. He added that a dead German was found near the magazine. Goldberg was the man who had been on the Boston Express and had taken the glass out of the child’s eyes. His train then turned around and headed to Truro. The only glimpse he had of the harbour was from his broken train window. The report said he got this information in a “roundabout” way: it came “from a railroad official who said it was given him by a member of the municipal government in Halifax.”

The New York Sun filed a story stating that the “Ioma” [sic] had not collided with Mont-Blanc by accident, but had rammed the ship to try and make it sink. The reporter said, “a Canadian officer who refused to allow his name to be used” told him that the Mont-Blanc had caught fire at the docks, and that when the fire could not be put out the vessel was towed out to the harbour. The captain of IMO took what the reporter called a “100 to one chance” and risked the lives of his crew by ramming the burning ship. The reporter said his informant had told him the fire on Mont-Blanc had been set: it was a German plot. Although no byline appeared on the story, it was filed from Bangor, Maine, the day John Tresilian of the Sun passed through en route to Halifax. Since his train stopped at Bangor for thirty minutes, he must have written his story on the train, jumped off, and handed it to the telegraph operator. The Daily Kennebec Journal in Augusta, Maine, ran it on page one under the caption “AN INTERESTING STORY.” The Toronto Daily Star buried the same report on page seven and said, “Little credence was given to it.”

Tresilian, at least, managed to get his stories to his newspaper. When Stanley K. Smith stopped long enough in Truro to gather a story about what was happening there, he typed it up as the train continued toward Halifax and handed it to the station operator at Stewiacke. Smith told what happened in a story he wrote later for the Star: “A rotund agent held the key and he welcomed me cordially but I am sorry to say his smile was a delusion and a snare. After two days in Halifax, I arrived home about the time the first despatch came through from Stewiacke.” Despite the two-day delay, the Star ran the story, one of the few accounts published of how the Truro Academy, Court House, and fire hall became emergency hospitals.

OTHER ERRORS

In London, The Times contented itself by reporting what its correspondents picked up in Ottawa and New York, some of it accurate, some of it horribly distorted. One day its report, headlined “THE RUINED CITY OF HALIFAX,” started with an admission that it was scalped from the New York papers, then went on to report totally inaccurate details about what happened:

Through streets covered with three feet of snow, the correspondents of the New York newspapers made their way yesterday through the devastated districts of Halifax. Their reports of what they saw are harrowing beyond belief. One of the most harrowing discoveries was the bodies of 200 children in the ruins of the Dartmouth school. Of the 550 boys and girls who entered certain schools in Halifax on the day of the disaster, only seven are known to have escaped with their lives.

That same day, it carried a report from Ottawa quoting the prime minister, Sir Robert Borden, as stating the death toll would reach 10,000. The next day it admitted that was a telegraphic error—the figure should have been 1000. It was one of the few times any paper admitted an error.

The Toronto Daily Star said that the ship Mont-Blanc collided with was a Red Cross hospital ship. That forced the Red Cross to say that the only hospital ship that had been in Halifax that week was the Florizel, that it had sailed on Tuesday, two days before the explosion, and that it was now in Newfoundland. Normally, due to the war, reports naming ships or describing troop movements were strictly forbidden. The Star also reported that the business district of Halifax was completely wiped out. It based that report on an interview with J.S. Carroll, a telegraph operator in its office in Toronto. He had once lived in Halifax. He was shown the incoming news reports and he said that is what must have happened. In fact, most stores and businesses had their windows blown out, but most offices were open the following day.

The Ottawa Journal’s Grattan O’Leary, later the Journal’s editor, wrote a story for his paper that described IMO’s pilot, William Hayes, as “conscientious, sober and with a record as a pilot unmarred by a single mishap.” How could such a man, he asked, have made such a terrible mistake? O’Leary’s answer was that he had been reliably informed that Hayes was not on the bridge when the collision occurred. O’Leary presumably got that from Mont-Blanc’s pilot, Francis Mackey, but it was, of course, untrue. Mackey was trying to convince everyone that IMO had made the crucial error and that this would not have happened had Hayes been on the bridge.

One story the Americans did get right was that there was over-response. At the request of the Halifax Relief Committee, R.W. Simpson filed an AP story that got widespread coverage in the United States:

Halifax, Dec. 10—Deliverance from its friends is the immediate urgent need of this stricken city….

Shock, fire, wind and deluge have followed in succession like the plagues of Biblical lore but the spectre that has caused dismay is the threatened invasion of former residents, friends of the injured and missing and merely curious. They arrived in the hundreds. They are coming in thousands if reports are true. Every trainload adds to the problems, already infinitely difficult.

That story was somewhat ironic, for one of the converging groups was the news media itself. The first train from Boston carried five newsmen—Richard Sears of the American, A.J. Philpott of the Globe, J.V. Keating of the Herald, Roy Atkinson of the Post, and Simpson himself. The train from New York had P.T. Jones of Brooklyn, a newspaperman, John Tresilian of the New York Sun, Charles Rucker of the Universal Film Company, and a man named Harrison of the Mutual Film Corporation. (The film people made movies of shattered Halifax that attracted huge audiences in the United States.)

EUROPEAN COVERAGE

In Paris, the first news reports were skimpy. They said there had been a massive explosion in Halifax and that half the city was destroyed. They tried to put the story into context by reporting that Halifax had a population of 55,000 and was an important North American port. Most papers said the explosion resulted from a collision between two ships and that one was “français, chargé de munitions.” The other was described as a Belgian relief ship. In Mont-Blanc’s home port of Bordeaux, La Petite Gironde, under the headline “EPOUVANTABLE DESASTRE LA VILLE DE HALIFAX,” reported that a French ship, loaded with ammunition, collided with a Belgian ship. (IMO was Norwegian, but the fact it was chartered to carry relief supplies to Belgium continued to confuse editors.) It compared the explosion to the eruption of Mont Pelée, the volcano in Martinique.

Unfortunately, while a paper such as Le Matin used its own correspondent and gave the story extensive coverage, others provided little information, and much of that was inaccurate. A number, obviously anxious to find some French heroes, said that the French ship had caught fire after the collision and that the crew stayed on board to fight the fire. This, they reported, led to the deaths of all those on board the French ship. The naval ministry in Paris was reading those reports, and believing them, for it dispatched wire after wire to North America asking for news about what happened. When the French embassy in Washington—after checking with its consul—reported that the only French crew member killed was Yves Gueguiner (one of the gunners) and that three others had received slight injuries, they wired again: “Confirmez … urgence que cannonier Gueguiner est le seul victim.” The ambassador replied again: “Gueguiner, Yves, est le seul victim décédé à suite de l’explosion Mont-Blanc.”

The French press was unclear about the origin of the other ship, sometimes calling it American, sometimes Norwegian, always calling it the Iowa. (Presumably the suggestion the ship was American resulted from the incorrect name Iowa, a risky assumption, since Chicago, one of the ships in Bedford Basin, was a French ship.) Reports quoting a Canadian physician stating the carnage in Halifax was worse than he had ever seen in France identified him as McKenzie rather than McKelvey Bell. Canada’s prime minister was called Sir Robert Gordon, not Borden, perhaps a reflection of how little the French knew about Canada’s role in the war. All the reports were brief. L’Humanité carried just two paragraphs of news on the incident.

In Norway, however, the story received front-page attention. Aftenposten, the leading paper in Kristiania (now Oslo) headlined: “KOLLISION MELLEN 2 DAMPSKIBE—HENVED 1,000 OMKNONNE.” Rather than focus on the destruction in Halifax, the Norwegian reports stressed that 36 of the 42 members of the IMO had survived, and that all but five members of the crew of another Norwegian ship, Hovland, had survived as well. (The Hovland had been protected from further damage by the dry dock.) That emphasis was not surprising. Norway’s shipping had been subject to repeated attacks by German submarines. Sometimes the crew was rescued. More often the entire crew was lost at sea. Before the war ended, roughly half of Norway’s substantial merchant fleet would be lost to enemy action. Reports of two Norwegian ships where almost all the crews survived was positive news indeed.

In IMO’s hometown, the Sandefjords Blad reported that the wife of Captain Haakon From had been notified that her husband, the first mate, and four other crew members had been killed in the explosion. The paper ran a brief obituary on Captain From. Eventually, many of the surviving crew returned to Sandefjord. Sigurd Olsen Hunstok became well known, both because he repaired typewriters, a job that gave him lots of contacts, and because he performed his tasks with one arm.

When Mont-Blanc exploded, Hunstok was blown from IMO’s bow to her stern. His left arm was badly injured and was amputated—in three separate operations. Since Hunstok was left-handed, he had to learn how to do everything with his right hand. (Canada told him it regretted his injury and gave him $100 to cover the loss of his arm.)19

FIGURE 16.1 | Per Hunstok with a painting of IMO, painted by a friend for his grandfather Sigurd Olsen Hunstok, who lost his left arm to the explosion. A copy of the painting hung in Professor Scanlon’s living room. With permission, Per Hunstok and Sandefjords Blad.

CENSORSHIP

The initial news reports on the explosion were surprisingly detailed in view of the fact that newspapers (in fact, all publications, together with the land telegraph lines that carried most of the news) were under the control of the chief press censor, Ernest J. Chambers, in Ottawa. His mandate was to prevent publication of information about the Canadian or Allied war effort that might be of use to the enemy. This included “movements, numbers, description, condition or disposition” of armed forces and of merchant vessels carrying troops or war supplies; similarly restricted was information on defence installations, including harbour facilities for war transport operations. Nor was that all. “Objectionable material” liable to censorship included “any report or statement intended or likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty or to interfere with the success of His Majesty’s forces or of the forces of His Majesty’s allies by land or sea.” This broad category embraced everything from wilful sedition to unsubstantiated rumours that might spread alarm and undermine support for the war effort.

Chambers’s appointment was in the department of the Secretary of State. This department was a catch-all for functions that did not readily fit into the mandates of other departments, and could exercise authority in matters beyond strictly military or naval concern, which experience early in the war showed to be essential in controlling the press. The militia department, which on mobilization in 1914 had been the main authority for censorship, was still responsible for the censorship of the transoceanic telegraph cables that landed on Canadian soil. The official in charge at Militia Headquarters in Ottawa was Charles F. Hamilton, who, like Chambers, was a professional journalist and long-serving officer in the militia well known to senior officers and political figures alike. Because the British government took control over all ocean cable communications within the Empire during the war, Hamilton was under direction from the British War Office. At the same time, he worked hand in glove with Chambers on any press material that came to the ocean cable companies.

Major-General Benson’s staff in Halifax included a censorship section, run by a retired militia colonel, Arthur E. Curren. Curren reported to Hamilton in Ottawa and also assisted Chambers in control of press stories transmitted both by land telegraph and ocean cable. This close co-operation had been inherent in Chambers’s position from the time of its establishment in 1915—it was the militia and naval departments that had made the case to the government for the appointment of a press censor with wider authority than the military and naval censors.

Ernest Chambers, with his continual close contact with the press and telegraph companies, was likely the first government official in Ottawa to learn of the Halifax disaster on the morning of 6 December. Indeed, items passed to the service chiefs by Chambers were the only definite news that militia and naval service headquarters in Ottawa had of the disaster until landline communications were re-established with Halifax late in the afternoon.

Chambers was probably also the first official in Ottawa to take action. His instinct was to head off the wild speculation and rumours that propagate with lighting speed in a crisis by issuing a statement to the media with the essential facts. He immediately sent a message through the naval wireless system to Curren in Halifax asking him to draft and release to the press a statement with the best local information he could get. The message, however, never reached Curren, probably because of the chaotic situation in the badly damaged naval dockyard. Chambers also urged the head offices of the telegraph services in Montreal and Toronto to have their people do everything they could to help journalists on the spot: “In view of contradictory reports abroad regarding Halifax explosion, I hope everything possible is being done to facilitate transmission of press reports. This most desirable from a national point of view.” He then telegraphed the head of CP in Toronto late in the afternoon of the 6th, at around the time the landlines to Halifax were first repaired: “Considering the gruesome and exaggerated character of reports in circulation about Halifax Explosion I have requested both telegraph companies to give their every facility for transmission of press matter. Can I do anything to help your service and have you found any interference other than that due to injuries sustained by telegraph plants?”

This commitment, however, resulted in Chambers being sharply criticized by name in the Ottawa Evening Journal on 7 December in an article entitled “Official Red Tape.” Canadian Pacific Railway Telegraphs had refused to transmit a report, citing a block placed by Chambers on stories about the disaster. The complaint had already reached Chambers on the morning of the 7th, and he asked Hamilton if Curren’s staff in Halifax might have got wrong instructions. Hamilton replied that he had blocked the transmission of news items over the ocean cables temporarily, but had not interfered with the operation of the landline telegraph services. Curren’s response to the complaint vividly depicts the circumstances in the city:

With the several members on my staff I endeavoured as far as possible to expedite all press matter recognizing that it was most desirable the people of Canada and the United States be immediately informed through the newspapers of the terrible disaster which has happened at Halifax.

I may point out some of the difficulties which existed on the 6th and 7th instant. First—the explosion destroyed in the vicinity of Richmond all the wires controlled by the Western Union and C.P.R. Telegraph Offices, consequently, Halifax was cut off.

Within two hours of the accident, automobiles were procured and all telegrams which had been filed were sent by motor car to Truro and transmitted from that point. This naturally was effected only after a delay of some hours.

Other telegrams including press matter were transmitted from Halifax to North Sydney by land lines, from North Sydney to New York by submarine cable. Others again were transmitted by submarine cable direct from Halifax to Rye Beach [New Hampshire] and from that point via Boston to Montreal and Ottawa.

During the night of December 6th owing to a violent snow storm the Land Lines in Cape Breton were torn down, and connection with North Sydney was thereby cut off.

On the morning of the 7th a large steamer dragged her anchor in the entrance of Halifax Harbour and in so doing broke the cable between this port and Rye Beach. As a consequence without connection at North Sydney—without connection at Rye Beach—without connection by land lines to Truro—it was impossible to transmit anything by ordinary routes, and it was until 11.P.M., on the 7th that the gangs of men at work were enable to reconnect Halifax with Truro….

In criticizing the newspaper item which appeared in the Ottawa Evening Journal of the 7th inst[ant] I may say that Military authorities at Halifax have not in any way interfered with telegraphic matters, and I may confirm what Colonel Chambers has already stated that no instructions of any kind were given the C.P.R. Telegraph people or the Western Union Telegraph people to delay any press matter.

On the 6th and 7th inst owing to the tremendous number of telegrams sent in to the two offices by thousands of people these offices were taxed beyond their ability to handle the traffic promptly for reasons already given, but as I have already stated Press Matter was given the right-of-way in every instance.

To Chambers, Curren explained that some messages inevitably escaped examination: “I endeavoured to restrain correspondents from sending out sensational head lines; but as our wires were all down a lot of telegraphic matter was sent by motor car, and by train, to Truro or other stations on the Intercolonial railway, and quite a number of exaggerated statements were consequently published in many of the Canadian and American papers.”

In general, the censors allowed full coverage of the accident, and applied the regulations only to specifics concerning the larger military and naval presence in the city and to anything touching on convoy operations. Thus there were reports about the British, American, and Canadian naval relief parties, but, aside from information about the casualties in Niobe, no mention of the names of warships. Similarly, while there was much information about IMO and Mont-Blanc and some of the merchant vessels, such as Picton, that had been badly damaged and suffered losses to their crews, there was no mention of the dozens of undamaged ships awaiting convoy. Likewise, reports on the garrison included the role of troops in rescue work, the damage to the Armouries and Wellington Barracks, and casualties at those places, but not the units in the city or information about other military facilities.

BOSTON SPECIAL

The explosion occurred during a peak news period. In the Middle East, the British had captured Jerusalem, the first time since the Crusades. In Russia, the Bolsheviks were taking over after the country’s brief flirtation with democracy. The Paris daily Excelsior ran two huge front-page photos. Under the headline “LENIN ET TROTSKY HARANGUANT LE PEUPLE,” the images showed Lenin and Trotsky surrounded by huge crowds. There was an ominous undertone to that news. It meant that the Germans no longer had a threat on their eastern front. They could start moving troops into the trenches, perhaps before the Americans arrived in force.

In the United States, reports from the war front showed American soldiers and sailors dying in increasing numbers. The week after the explosion, the first American warship was torpedoed by a submarine. More significant, the United States government was considering taking over the railroads to ensure that military personnel and war supplies were moved efficiently. Within days, those news stories were driving Halifax out of the headlines everywhere but in Boston. There, despite that there was a dramatic local story—a woman on trial accused of killing her boyfriend’s wife—the attention to Halifax continued.

The Boston Globe had 17 stories on 7 December, 27 on the 8th, 34 on the 9th, 9 on the 10th, 23 on the 11th, 14 on the 12th, and 11 on the 13th—136 separate stories in seven days. In that same period, the Herald had 117 stories and the American 59. Detailed information is not available for the Post, but it carried 20 stories in a single edition when it broke the story on 7 December. All the papers carried extensive coverage on page one, starting off with an initial main headline. On 7 December, for example, the Post headlined:

HALIFAX WRECKED BY TERRIFIC

EXPLOSIONS, OVER 2,000 KILLED

2 SQUARE MILES OF CITY A RUIN

That same day, the Globe headlined:

HALIFAX SWEPT BY FLAMES

AFTER EXPLOSION, 2000 DEAD

For three of the next four days, the story was still worth main headlines in the Globe:

EXPLOSION CUTS OFF HALIFAX (8 Dec.)

20,000 SURVIVING DESTITUTE (8 Dec.)

OFFICIALS PUT HALIFAX DEAD AT 4,000 (9 Dec.)

SOLDIERS TURN BACK VISITORS (11 Dec.)

Later, the Boston papers kept the story on page one but focused on the Massachusetts aspects of the response. On 13 December, for example, the Globe’s front-page story was headlined “BOSTON RELIEF SHIP ARRIVES IN HALIFAX.” That same day the American ran an inside story headlined “Christian Lantz of Salem asked to go by John F. Moors of Boston.” (Lantz had been involved in the response to a fire in Salem, Massachusetts.) While the coverage was extensive, some stories, especially in the Boston American, bore little resemblance to reality:

- Halifax, since England went to war with Germany, has been the chief Canadian seaport. It is the terminus of the great Canadian Pacific Railway. (American, 6 December. Halifax, of course, was actually the terminus for Canadian National.)

- More than 100 people are believed to have been killed following the collision of two munitions ships in Halifax harbour today. (American, 6 December. The death toll, of course, was much higher and only one of the ships carried munitions.)

The coverage got a little better when Boston reporters reached Halifax on Saturday morning. That was partly because, just as they arrived, the telegraph link to Boston was restored—as Maritime Telegraph and Telephone reported with pride:

An urgent demand was made upon us by the Press Association for facilities for direct telegraphic communication between Halifax and Boston. Handicapped and crippled though we were by the damage done to our toll plant by the storm of December 2nd, which had not yet been repaired, and by the havoc wrought to our lines by the explosion in the harbour, we found it possible, though difficult to comply with the demand, and by Saturday 8th (48 hours after the explosion) the line was in working order.

From then on, the coverage was from reporters actually in the city:

- A limp bullet-ridden body dangled from the post to which has been pinned this sign, “This is a looter.” It is the body of a man who was discovered looting in the devastated area. Colonel Thompson, “We have no objection in letting the public know the nature of the punishment in extreme cases of this kind.” (American, December 12) (See Chapter XI.)

- The police are rounding up all persons suspected of being subjects of Germany or of being Teuton sympathizers. (American, 10 December) (This was partly true: there was a roundup of German nationals but not suspected sympathizers.)

- It would have astonished a good many Boston people if they could have seen their favorite physician shoveling glass, putting in windows, making partitions. (Globe, December 13) (This was accurate.)

There were several reasons for Boston’s extensive coverage. One was that this was a big story and Halifax is close to Boston—the two are connected by railway. Another is that the story brought the war home to North America. As mentioned earlier, there were also strong links between Nova Scotia and New England because both were important educational centres. Many Canadians received their education in Boston, and many Americans, especially young Roman Catholic women, came to Halifax to go to school. Finally, there was the fact that there were so many Canadians in Boston and many had family in Halifax. The Herald waxed eloquent on 8 December when it described Haligonians as “our own flesh and blood, our kindred in peace, our allies in war.”

The most important reason for the coverage, however, was that all the Boston papers sent reporters to Halifax. When editors spend money sending reporters to cover a story in a foreign country, they have to justify that decision by publishing the results. As soon as Massachusetts announced it had made arrangements for a special relief train to leave at 10:17 p.m. Thursday—and that the train would travel to Halifax in record time (the normal trip took twenty-six hours)—the media climbed aboard.

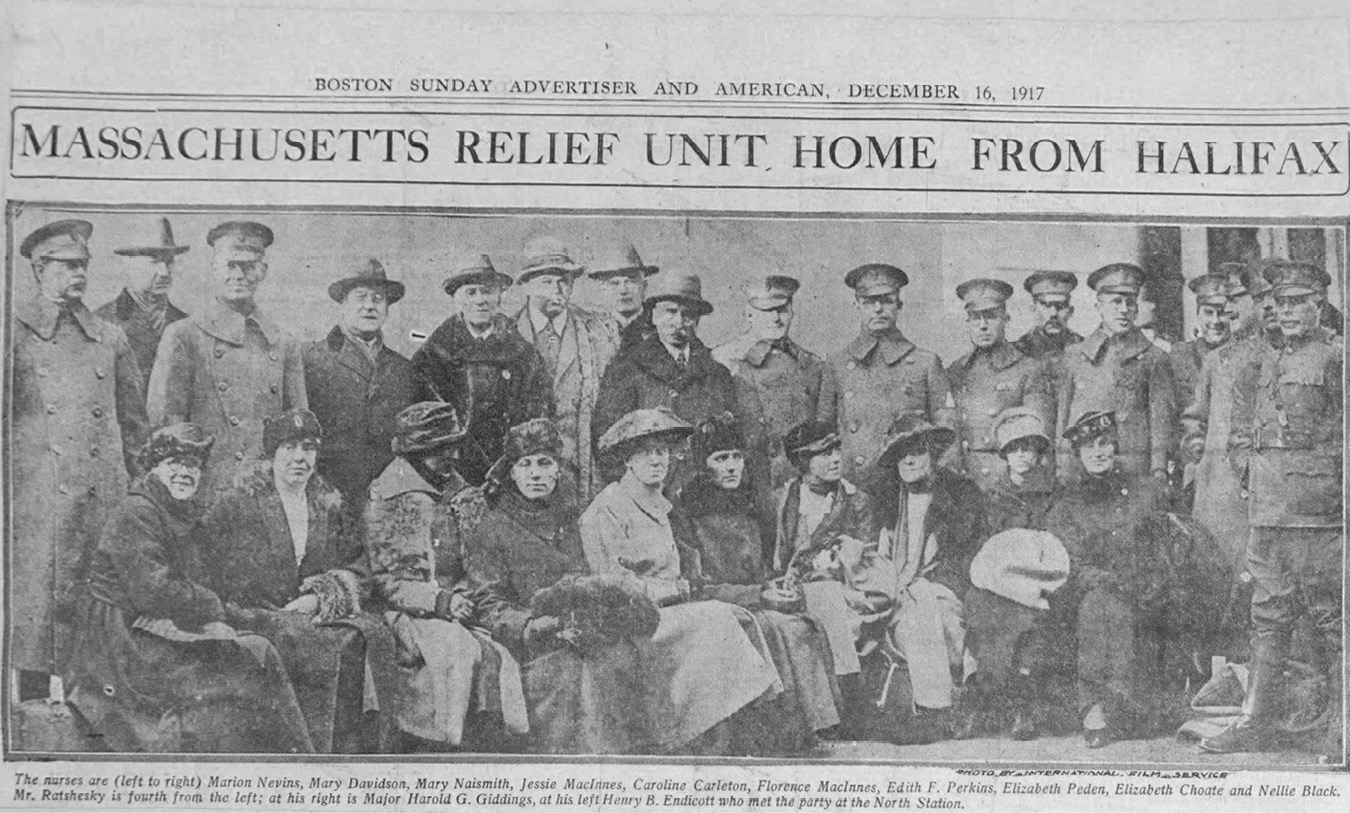

FIGURE 16.2 | American relief workers, including expedition leader Abraham C. Ratshesky (fourth from left, back row) return home to Boston, Massachusetts. Generous American response, which came by rail and sea, overshadowed the effective early response of the Canadians. Wyner Family Jewish Heritage Center at the New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

When the train left, it carried eleven physicians, ten nurses, Red Cross officials, clothing and medical supplies, and five reporters. For the next thirty-nine hours, those reporters struggled to find something to write about—a faulty engine, an accident on the line, then a major snowstorm held up the train. At stops such as Bangor, Saint John, and Moncton, they interviewed anyone who appeared to know anything. They flocked around Abraham Ratshesky, the expedition leader, who used the railway telegraph at each stop to try and get through to Halifax. Since there was little information, except the imaginative accounts acquired by hasty interviews with travellers heading the other way, the reporters gave their imaginations free rein.

VISUAL COVERAGE

In 1917, most newspapers were not photo conscious. They might run the occasional front-page photo and use a head-and-shoulders shot of a prominent figure, but words, not pictures, were their specialty. In the wake of the explosion few media used visuals. Some had maps, though these were not always accurate. Most confined themselves to stock shots—pictures showing Halifax the way it was before the explosion, including the picturesque Citadel. The Toronto Daily Star was different. It was one of the world’s most photo-conscious newspapers. When former president Theodore Roosevelt spoke in Toronto in November 1917, it carried a huge front-page picture of the crowd that packed the Armouries, labelling it, “A GLIMPSE OF THE GREATEST AUDIENCE EVER ASSEMBLED IN CANADA.” Its lists of war dead were usually accompanied by photos of individual soldiers. Picking up pictures of victims became a test of Star reporters’ commitment to their profession.

For the explosion, the Star used maps. It used stock shots. It obtained pictures of people in Halifax from their relatives in Toronto. One day, for example, it used letters from a Toronto man who had gone to Halifax to describe what had happened to that man’s son-in-law, James Fraser, an engine-room artificer on Niobe. The story was illustrated by a photo showing Fraser, his wife, Dora, and their son, Jim Jr., holding hands as they went for a walk. The Star even found a sister of Vincent Coleman in Toronto. (Coleman was the telegraph operator who died after sending the last pre-explosion telegraph message.) They ran a photo of Coleman’s children, Nita, Gerald, and Ellen. (There were four children in the photo and it was not clear who was who.)

Starting on 11 December, the Star ran front-page pictures for five consecutive days, ending with a full-page spread on Saturday, 15 December. The first day, it ran a rather unimpressive shot of the inside of a damaged home, but with it was the only photo of a fire engine in the burning North End. The photo also ran in several US papers and ended up as a postcard. The next day, the Star had photos of buildings in the business district, all with their windows blown out. On Thursday, it had a photo of the prime minister, Sir Robert Borden, standing in snow, looking at wreckage. It also showed a steeple, all that was left of Grove Presbyterian. On Friday, it showed more unidentified wreckage, the North End station, and a long shot in which it was barely possible to see IMO grounded in Tufts Cove. Saturday, it finally got a close-up of IMO, in which the sign “BELGIAN RELIEF” could be clearly seen on its side. It also showed the wreckage of the Richmond Publishing Company and stated that the bodies of thirty girls were still buried in the wreckage. However, it never carried a single photo of an injured survivor. In fact, except for the posed shot of the prime minister, it never carried photos of any victims or any players in the response. On 18 December, it ran what it called an “exclusive”—a photo of the cloud rising from the actual explosion, which clearly showed that, unlike the atomic bomb, there was no mushroom.

There are now hundreds of photos showing what happened in Halifax. There are photos of the wreckage of the Curaca and of IMO. There are shots of the damaged Hovland in dry dock, and of Hilford upside down in wreckage at the North End station. There are photos of the ruins of the Acadia Sugar Refinery and the wreckage of Oland’s brewery. There are photos of overturned railway boxcars, burned trolley cars, derelict homes, churches, and schools. There are also photos of injured victims—including a classic shot of Annie Liggins with her bandaged burned head. She was found alive in the wreckage of her home twenty-six hours after the explosion. There are photos of hostels where the victims found shelter, including shots of orphaned children celebrating Christmas. Those photos can now be found in places such as the Nova Scotia Archives, the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, the Dartmouth Heritage Museum, the William James family fonds in the City of Toronto Archives, and the collection of photos taken in 1917 by the Toronto Daily Star.

Anyone looking at those photos is struck by how different they are from those published at the time. One reason for the difference is, of course, time. By the time photographers reached Halifax by train, took photos—or got them from someone who had taken photos—and got the film back by train to a major centre such as Boston or Toronto, the story was starting to fade. Another reason was censorship. Ernest Chambers was in Halifax from 14 to 17 December 1917 to assist Benson in dealing with the press. One of the problems was photographers who did not follow regulations, which required them to work under the supervision of an officer assigned to escort them and indicate where they could and could not take photographs. Chambers met with representatives of the press to explain the regulations. He was pleased with their co-operative attitude, but he also published in one of his periodic circulars to editors a warning that publication of photographs taken without military supervision could result in prosecution.

However, there seems to have been something else at play: an unwillingness to run photos showing bodies or injured people or, for that matter, orphans. On the day it started running photos of the explosion, the Star said it would not publish some of those it had. The photos, it explained, were “too harrowing for publication.” It is hard to figure out what those photos were. A photo of nurses with scores of infant orphans seems sad, but certainly not harrowing. Strangely enough, the same restraint did not seem to apply entirely in Halifax. The Herald also ran a lot of photos, most of them, like the Star’s, of damaged buildings; but it did carry one shot taken inside the morgue at Chebucto School. It shows the rows of bodies covered with white sheets.

By the time of the explosion, news media worldwide were often faking news film. The British faked scenes from the First World War. (They even supplied the famed American filmmaker D.W. Griffith with 40,000 troops and artillery so he could fake scenes from the trenches. He had refused to honour a contract to make films of the battlefield because real trench warfare was not visually exciting.) There were errors in the visual coverage from Halifax. The Toronto Daily Star, for example, ran a map with a big X marking the site of the explosion as in the corner of Bedford Basin. Not to be outdone, the Toronto Globe ran a photo of Pier 6 with the caption, “It was while the steamers were leaving this pier that the collision took place.” But these were mistakes, not fakery. The one visual that might be open to question was the Star’s “exclusive” photo of the actual explosion. It appears authentic. It is too poor a shot to be otherwise.

NO SPECULATION

Strangely enough, the media avoided speculating about what had caused the explosion. Many papers ran editorials expressing sympathy for Halifax. All who did mentioned that it was an accident and not a German plot. The Mail and Empire, in the middle of its crusade to re-elect Borden and save Canada from Laurier, whom it saw as a German ally, nonetheless disavowed the explosion as German inspired: “As the mind reels under the force of the bad news from Halifax, the question comes to it, ‘What Hun hand did the deed?’ But this [appears] not to be traceable to German diabolism. It appears to be one of the accidents of the dangerous traffic in munitions.” In London, The Times took much the same position: “All events of this kind are suspicious in a war with enemies such as ours and the matter should be probed to the bottom, but it is reassuring to learn that so far no evidence of foul play has been discovered. Accident not malice would appear to have caused the terrible misfortune which the whole Empire deplores.”

While the Toronto Daily Star did not editorialize, it took the same position in its news columns. In a front-page story on 10 December, under the rather unrelated headline, “QUICK BURIALS A NECESSITY, WARMER WEATHER SETS IN,” it reported: “It has been suggested but without proof that German machinations had something to do with the wreckage of Halifax. There were stories afloat of finding a wireless outfit in the home of a foreign resident, of the capture of four Hun spies. The facts, however, point to an accident or blunder in bringing about the fatal collision in the Narrows.”

Even when the papers reported, usually on page one, that the helmsman of IMO, John Johansen, was detained as a suspected German spy, they did not speculate that he caused the explosion. They ran the item as straight news, adding that IMO’s solicitor stated that the whole thing was nonsense. That turned out to be the truth.

One Toronto paper, the Globe, took the lead in urging the government to see that all those affected by the explosion were properly compensated—and it did this on 7 December, the day after the explosion:

The vessel which caused the disaster through the explosion of its cargo of munition was engaged in the service of the Allied nations and the loss of life and property suffered by Halifax is in essence a war loss. Compensation should be made as a matter of equity out of international funds. Nothing that can be done will make up for the horrors through which the people of Halifax passed yesterday. They are as truly war victims as if their city had been laid waste by the enemy’s guns.

There was one exception to this pattern. Perhaps tired of the attacks on Wilfrid Laurier, especially the ones that accused him of being a friend of the Kaiser, the Island Patriot in Prince Edward Island, three days before the election, blamed everything that happened on the Conservatives and the current prime minister, Sir Robert Borden:

Munitions ships should not be docked, moved or subjected to the risks of collision with other vessels.

It is criminally negligent to place munitions ships at docks so near a large crowded urban district.

If the Borden government and its supporters had devoted one-tenth the energy and talent to anticipating and providing safeguards against such a disaster as that at Halifax, which they devoted to blackening and damming the reputation of millions of Canadian Liberals whose devotion to and love of the Empire during the war has been as untiring and increasingly shown, the disaster would have never happened.

Conditions existing at Halifax have been notoriously loose. It was long since recognized that the authorities there were living in a fool’s paradise….

The Tory newspapers tell us it is the poorest part of Halifax which has been destroyed as if there was any consolation in that fact.

It is usually upon the poorest classes, the wage earners and the toilers that the horror or a great public calamity falls with the most appalling force.

That was the only item spotted in any newspaper that raised the issue of community safety given the potential of the instruments of modern warfare. Even so, it raised only the issue of safe handling of such cargoes and did not imply there was any reason not to do so. Even those who opposed the government were committed to the war.

MEDIA NOT ALONE

The media were not the only source of information about the explosion. Personal letters played a large part as well. A few days after the explosion, seventeen-year-old Frank Loomer, the wireless operator on Niobe, wrote his mother in Auburn, Maine. After reading her son’s letter, Loomer’s mother took it to the regular Friday-night meeting of the Court Street Free Baptist Brotherhood at the home of F.E. Dillingham. There it was read out loud. Later she gave it to the Lewiston Daily Sun, where it was published on 18 January.

Loomer had posted his mother a brief letter the day after the explosion to let her know he was all right. Confident she had received his letter, he did not reply to an anxious telegram she had sent, which did not reach him for several days. In following correspondence, he offered more detail. Since the family had lived in Halifax until Loomer finished elementary school, he wrote about the impact of the explosion on people his family knew:

Mr. Wallace is alive but badly injured and his boy and girl are alive and in hospital with him but his wife is dead. (Lottie Wallace, 34, was from Shubenacadie.) I don’t know of any others we used to know who are dead.

George Blenkiron was in the Wellington Barracks and badly cut about the head. His father came and took him home.

He also described how the explosion affected him and others, and the damage to the city and to his ship, Niobe:

I met the boys from the Naval College who were streaming with blood. Then I knew there must have been widespread destruction. The horrid screaming of the poor little fellows caught in the ruins of the Naval College made me sick and sick and shivering and I got away from there as quick as possible. I was as black as a coal miner and covered with dirt, but that was all the damage I got beside losing my cap.

The wires and poles were snapped in pieces and the station roof fallen in, and the King Edward Hotel was an empty shell, as well as many buildings on North Street.

The old boat is a sight. Her funnels are twisted some, part of one is torn off and all the woodwork, which was built over her, was knocked into kindling wood.

Loomer’s letter was one of many written from Halifax, and not the only one shared or passed on to a newspaper. Roy Laing was a bank teller and his letter home was published in Charlottetown. Clarence Delaney was an American sailor, probably from Old Colony, and his letter was published in his hometown in Massachusetts. These letters are an important part of the history of the explosion and the way news about it spread at the time. After sharing it with her church, Loomer’s mother kept her son’s letter and eventually passed it on to his wife, who lost it when she moved, but remembered hearing it had been published. A librarian in Lewiston found it in the newspaper and copied it for her. She wanted it for her granddaughter in Sackville, New Brunswick. Today it survives as part of that family’s legend. There are many others like it.

Another important source of news was travellers. When the various universities and colleges closed down, the students headed home. On arrival, they were besieged for information by family and friends and relatives and the media. When John Cranwell of the Salvation Army accompanied his wife’s body back to Ontario, he was pestered by reporters at every station along the way. In many communities, such interviews became an important part of the record of what happened. When Wilfred Godfrey, a student at Dalhousie, reached Charlottetown, he told the Island Patriot that physicians had been unable to cope with the number of injured (true) and that there were scores of premature births that night (impossible to confirm). Another traveller, Alfred Houston, said he heard a noise like a heavy cannon: “Then the roof of the market crashed in just by where I was standing and one of the roof planks fell on my right shoulder and fractured it. I ducked my head under a table to escape the glass which was flying in all directions. I could see people running on the streets, injured, some of them with terrible wounds.”

Interest in the explosion was not confined to the Maritimes or to the period immediately after it happened. On 6 December 1967, the fiftieth anniversary of the explosion, the Sandefjords Blad, in Norway, carried interviews with four former crew members of IMO.

Stories survive not just because they are occasionally reported in the press, but also because family memories have passed from generation to generation. Even today, those who were not yet alive can tell stories they heard from their parents or grandparents. The town clerk of Bridgewater heard what happened from her grandmother, Jennie Heisler. Heisler was a nursemaid in Halifax and had water boiling on the stove for the baby’s morning bath. When the explosion rocked the house, she grabbed the baby and ran to the bedroom. The baby’s mother was in bed, her eye cut by a falling stovepipe. Heisler says, “I can’t understand why they had a stovepipe over the bed.” A day or so later, she visited the morgue, looking for her cousin. She will not talk about that visit—some memories are best left alone. Happily, she later learned her cousin had survived.

Elsie Cranwell heard what happened from her father. He was with the Salvation Army in Halifax and his wife was killed by flying glass. He remarried and would never talk about the explosion in front of his second wife; but sometimes he would tell his story to his daughter. Marjorie Cox’s father not only told her about going to Halifax—he was a Methodist minister and wanted to help—but left her the pass he was issued.

Gordon Hansford heard his mother, Cora Balcom, tell her story so often he rhymes it off from memory. Balcom, seventeen, was working at the Green Lantern restaurant and had the day off. She was walking along Barrington Street when Mont-Blanc exploded: “Everything was going absolutely haywire…. All of a sudden I realized there were people roaming about with blood running down and the windows were all broken. I had a white dress. When I looked down, I was coal black from head to foot. I had a piece of glass maybe eight to 10 inches in my hair, which was piled up, the way we used to wear it.” Balcom thought she was black because she was passing a coal yard; but others turned black from the coal dust and oil thrown up by the explosion. When Thomas Raddall saw the first bodies at the morgue at Chebucto School, they were so black he assumed they were from Africville. A layer from that black rain is still in the earth in the city’s north end.

The curiosity about what happened three-quarters of a century ago lingers on. Used bookstores have no trouble selling books, postcards, and other mementos of the explosion, and the former director of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, David Flemming, regularly received letters from people telling of their experiences. Even in Sandefjord, Norway, a policeman, Per Hunstok, keeps the records of his grandfather’s service on IMO, the ship that collided with Mont-Blanc before the explosion, and planned to visit Halifax,20 where his grandfather lost an arm. A priest in Sandefjord cared for the grave of IMO’s captain, Haakon From. From was killed in the explosion and his body shipped home. The priest knew one of his daughters.