INTRODUCTION

THE MANUSCRIPT ON THE HALIFAX EXPLOSION THAT PROFESSOR Joe Scanlon substantially completed was the product of a long labour of love. He toiled in major archives and libraries on both sides of the Atlantic. He travelled to any smaller centre where there might be records squirrelled away or people who had personal or family memories. A journalist by training, he had a nose for the good story, and out-of-the way sources that had been forgotten or overlooked.

The manuscript grew out of his academic career in disaster studies, a field in which he was a pioneer, and in which he produced scores of scholarly articles. The manuscript draws on many of these articles, and is something of a capstone on his academic research. Yet he evidently did not intend to produce an academic book. Rather than clutter the text with footnotes, he harkened back to his roots in journalism by appending a lengthy essay on sources, which appears in the present volume. The essay reads like a reporter’s notebook, recording the contacts he made and the leads he followed in the course of his numerous research excursions. The sources he uncovered are sometimes described in general terms, but in many instances full references can be found in the articles he published on the Halifax explosion between 1988 and 2000. Some of these were early drafts for parts of the book manuscript and therefore valuable in assessing its accuracy.

The manuscript that I initially reviewed was complete in contents, but with segments of early and later drafts mixed together. Later I was delighted to receive a version that had been edited by Professor Scanlon’s son David, who had enlisted the help of Barry Cahill, an expert on the Halifax Relief Commission and on the broader history of the city and the Atlantic region. David also supplied excellent research to resolve technical marine navigation issues in the analysis of the collision between the ships Mont-Blanc and IMO that led to the explosion. He was overly modest in suggesting that his and Barry’s work might possibly be of some help. In fact, David and Barry had addressed many of the issues I had identified prior to the first round of revisions. I immediately began to work from their draft, and was thus able to press on with additional research to clarify some passages, fill gaps, and flesh out sections where new information pertinent to Professor Scanlon’s insights had become available. David then generously responded to my request that he review my work as it progressed, for the benefit of his editorial hand and knowledge of his father’s approach to research and writing. It has been a fruitful and pleasurable collaboration.

All the changes in the manuscript are “silent,” as they in no way alter the argument or storyline. Where additional sources have been used to address a specific point, they are identified in endnotes following the main text. Sources used for general review of the original manuscript and updating parts of a few chapters are included as footnotes in the relevant sections of the sources essay, Appendix A.

Aside from David’s encouragement and help, I must thank Halifax historian Jay White, who shared his distinguished work on the role of the Halifax military garrison in the disaster and assisted with research in the Nova Scotia Archives. John Griffith Armstrong, once a colleague at National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa, is the author of the finest scholarly book on the disaster and provided his research files on key topics. I have peppered John with questions about the explosion and soaked up his learning since he began his research more than twenty years ago. Mike Bechthold, another old friend and collaborator in the salt mines of historical projects, designed the maps, with his unerring eye for detail and flair for effective presentation. Melissa Davidson, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Ottawa, carried out research in Ottawa with efficiency and good humour no matter how unreasonable the request or how great the rush. Siobhan McMenemy of WLU Press invited me to edit the manuscript, and has been a model of patience and support, invariably making time even as deadlines loomed to follow up unexpected research leads. David and I are grateful to copy editor Rob Kohlmeier and managing editor Murray Tong for their work.

Professor Scanlon framed the work as a tribute to Reverend Samuel Prince, the author of perhaps the first scholarly disaster study, which appeared a century ago. Prince, who was in Halifax at the time of the explosion, did a sociological analysis of the response of the community to the disaster as his Ph.D. dissertation. While celebrating this early, innovative effort, Professor Scanlon applied modern disaster analysis to turn Prince’s conclusions on their head. Prince saw a community reduced to chaos that had to be rescued in the days and weeks after the explosion by outside experts who arrived with the relief expeditions from the United States and central Canada and overrode local arrangements. An intellectual of his times, Prince saw social order as exceedingly fragile, and needing the guiding hand of professional expertise—administrators with credentials—to make a fresh beginning in the wake of disaster.

The story that Professor Scanlon tells is a more inspiring one. He shows how the people of Halifax and their neighbours in other communities in Nova Scotia and the Maritime provinces responded swiftly, intelligently, and compassionately to scenes of devastation. They rescued those in danger, provided medical care for the injured, shelter for the homeless, and food and clothing for all who needed them. People did what was most important and urgent, with the help and guidance of local authorities that proved robust and flexible.

What the officials from outside did not understand when they reached the city in the days after the disaster was that, ghastly as things appeared to them, the people on the spot had already capably dealt with circumstances that had been far worse, indeed beyond imagination. Further recovery measures put in place in the weeks following the disaster strove above all to bring order in accordance with the ideas of outside experts. These measures were often insensitive to the needs of those whose lives had been most profoundly disrupted—those already in poverty who had lost what little they had.1 This insensitivity, as Professor Scanlon emphasizes, was not a pattern exclusive to Halifax in 1917, but one that has been repeated time and again to the present day. People in the vortex of disaster tend to do the right thing. Outside agencies have difficulty finding their bearings in the midst of chaos, while responding as they must to external imperatives from their political and financial masters.

NAVAL AND MILITARY CONTEXT

The central fact about the Halifax disaster is that it took place in wartime as a direct result of war operations. Halifax was Canada’s most important naval and military port and a key asset for the Allied powers. By 1917, the Allied effort in Europe was dependent upon supplies transported by sea from North America, and Halifax was a vital hub in this supply system. The success of German submarines in attacking the cargo ships that crossed the Atlantic brought Britain to introduce more effective defensive arrangements, in which Halifax played a central role. This was the reason why the disaster occurred. The Mont-Blanc had loaded her lethal cargo of explosives in New York, and was inward-bound to join a merchant ship convoy assembling at Halifax for passage under the protection of British warships to Europe. IMO, which collided with Mont-Blanc, was outward-bound from Halifax, where she had put in for a security inspection before proceeding to New York to load cargo. Both ships, in other words, were at Halifax solely as a result of wartime measures for the defence of shipping.

Paradoxically, Halifax’s wartime role was also key to the effective early response to the disaster. The military garrison that protected the port included more than 3000 troops. More than 1500 other troops were in the city preparing for transport overseas. There were also special military medical facilities for the reception of injured and sick military personnel returning from Europe. Although the Canadian navy’s dockyard and its only large warship, HMCS Niobe, were severely damaged in the explosion, major British and American warships in port were not. The military and naval commanders, all of whom survived the blast, immediately lent support to municipal authorities with all the considerable resources at their disposal: trained and disciplined personnel for rescue and work parties, medical staff and facilities, and supplies of all kinds.

One of the contributions of Professor Scanlon’s work is that it makes full use of the substantial military records of the explosion and recovery, including documents he was the first to bring to light. The manuscript, however, does not refer to naval and military historical scholarship that provides essential context. This includes the reasons for the mixed British and Canadian naval organization at Halifax, the special difficulties of the young Canadian navy that left the service vulnerable to attack by the public and press, and the history of the well-established Canadian army command at Halifax that accounts for its achievements in the relief effort. This context, in fact, strengthens Professor Scanlon’s central argument about the need to focus on the local circumstances, people, and events. The contextual material he did use—general histories of Halifax and Nova Scotia written before many government documents were available for research—had the effect of obscuring the manuscript’s thrust. The editor has therefore removed these few pages and offers the following account as an introduction.

HALIFAX AS A BRITISH NAVAL AND MILITARY BASE, 1749–1906

Halifax harbour is deep and large and the closest ice-free major port on the mainland of the Americas to western Europe. The inner harbour extends some sixteen kilometres north from the northern tip of McNabs Island to the head of Bedford Basin, a natural anchorage that extends north of the Halifax waterfront for more than six kilometres. The basin is nearly four kilometres across at its widest point. Thrust out into the north Atlantic on the Nova Scotia peninsula, the harbour is on the short Great Circle route across the ocean. It is 1300 kilometres nearer to Southampton in southeastern England than New York, and 750 kilometres closer than Boston. For a fast cargo steamer of the early twentieth century, that made a difference of more than two-and-a-half-days’ sailing in the case of New York and nearly two days from Boston.2

What the Indigenous Mi’kmaq called Kjipuktuk (Chebucto in the English rendering)—the great harbour—was the logical choice for a settlement when in 1749 Britain established a stronger presence in mainland Nova Scotia. The objective of the settlement at Halifax was to counter continuing dominance by the French and their Indigenous allies in what the French named Acadie (Acadia). The pressure behind British expansion into the area came from Massachusetts, the original English settlement on the northeast coast of what is now the United States. Determined to eliminate the economic competition and military threat from the French and their Indigenous allies, the English colony raised a force from its own militia and persuaded the British government to supply naval support for an expedition that seized Port Royal, the capital of Acadia, in 1710 during the European War of the Spanish Succession. At the end of that conflict in 1713, the whole of what is now Nova Scotia, save the island of Île Royale (Cape Breton), passed to Britain. The French, however, built the fortress port of Louisbourg in Cape Breton to maintain their fishery and trade, and their alliance with the Indigenous peoples. In 1745, during the War of the Austrian Succession, Massachusetts mounted another militia expedition, this time against Louisbourg. This effort succeeded in part because of large-scale support by warships of the Royal Navy assigned to the West Indies, one of the navy’s first overseas stations. The northern operations marked the beginning of the navy’s North America station. In the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle that ended the war in 1748, Louisbourg passed back to French control.3

The British government established Halifax in the following year to counter Louisbourg and assert British power over the Atlantic region. In the Seven Years War (1756–63 in Europe, though the conflict had broken out in 1754 in North America), the British government made the conquest of Canada a primary objective. Halifax was the staging port for the large British naval and military expeditions that took Louisbourg in 1758, Quebec City in 1759, and the subsequent operations up the St. Lawrence River that brought Canada into the British Empire as the new colony of Quebec in the peace of 1763. To keep the large number of ships operating from Halifax in good running order, in the summer of 1758 the Royal Navy established a dockyard at Halifax, on the same harbour shoreline that is the Royal Canadian Navy’s main Atlantic base to this day.

With much of North America in British hands, Halifax became a military and naval backwater, though for only a few years. The revolution of the American colonies against British rule in 1775–83 nearly reversed the city’s strategic role. It had been founded as the forward bastion for the protection of the old British colonies against the French and their Indigenous allies to the north. But now Halifax looked south, a bastion to protect the new British colonies in the north against the United States. Once again Halifax became a military and naval entrepôt that allowed Britain to fight a war far distant from her shores. When the British forces at Boston had to withdraw in 1776, they were able to come to Halifax and from there mount the expedition that seized New York as the main centre for operations. Warships based in Halifax protected the shipping that sustained the British forces fighting the Americans and, from 1777, their new French allies.

The outbreak of war between Britain and revolutionary France in 1793 had early repercussions in the western Atlantic, where British warships sought to check the large seaborne trade between the neutral United States and France. This was a key issue in the American declaration of war on Britain in 1812 and its invasion of Upper Canada. Halifax again became the entrepôt that secured supply lines to the British forces on the remote Upper Canadian frontier and, more important, a base for British naval operations that interdicted seaborne trade on the American Atlantic coast, inflicting economic losses that persuaded the United States to conclude a peace in 1814.

In the wake of the War of 1812, the British government undertook a major defence construction program in its North American colonies to guard against future aggression from the US. At Halifax, the fortifications around the harbour were strengthened, notably with the building of the star fort on Citadel Hill, which still dominates the downtown. Another major project was the construction of the brick Wellington Barracks near the waterfront in the northern part of the city, on the rising ground just north of the naval dockyard, in the 1850s.4

Even as Halifax became more firmly established as a British Army garrison town, in 1820 the dockyard reverted to use primarily as a summer station. Bermuda became the major Royal Navy base in the now-combined North America and West Indies station, because of its salubrious climate and strategic position between Britain’s possessions in the Caribbean and the northern fisheries and shipping lanes. The warships that came north each summer were normally cruisers and smaller types largely committed to enforcing treaties governing American and French access to the fisheries of Atlantic Canada and Newfoundland. In times of crisis with the United States—the cross-border insurgency during the 1837–38 rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada, and then the boundary disputes between Maine and New Brunswick and in the Oregon territory on the Pacific coast between 1839 and 1846—Britain reinforced its army garrisons in North America and dispatched major warships to the station.5

The greatest danger came in the 1860s as a result of the American Civil War. British neutrality, and its claim of the right to trade with the breakaway Confederate states, brought Britain and the Union government to the brink of war, which would have meant an American invasion of Britain’s North American colonies. Britain sent large reinforcements. In the case of the army the strength of the garrisons increased from 4000 troops in 1861 to nearly 18,000 troops, with the share in the Maritimes, mostly at Halifax, rising from 2000 to 4000. After the end of the Civil War in 1865, there was a continuing threat from Irish-American Fenians. In the spring of 1866, they massed in Maine on the border of New Brunswick, and then attacked across the frontier at Fort Erie in Canada West (Ontario). These events, and intelligence of Fenian efforts to organize new expeditions, kept the British forces at high levels until 1869. Major warships remained on station at Halifax, which also served as the base for the dispatch each spring of naval forces that patrolled the St. Lawrence and Lakes Ontario and Erie until the winter freeze-up.

The Civil War and Fenian crisis brought great changes in British North America. Most important was the confederation of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Canada East and West into the Dominion of Canada, in 1867. British and colonial leaders alike realized, with the rapid mobilization of vast military forces by the US during the Civil War, that the colonies had to combine their resources for survival. One of the benefits, foreseen by British leaders, was that the new, democratic federation, modelled in some respects on the Americans’ own federation, would not arouse the anti-British sentiment in the US in the way the Crown colonies had done.6

The British also supported confederation in order to escape the crippling costs of defending the colonies. After Britain and the United States resolved the main issues arising from the Civil War in the Treaty of Washington in 1871, Britain immediately withdrew all the army garrisons from Canada except for the troops at Halifax. Halifax was essential to the Royal Navy’s dominance in the North Atlantic, which was the foundation of Britain’s security, economic strength, and ability to project power around the globe. Even as the last British troops in the interior sailed from Quebec City in 1871, the British army rebuilt the harbour forts at Halifax and rearmed them with the latest heavy rifled guns that had proved themselves in the American Civil War.7

CONFEDERATION AND THE MODEST BEGINNINGS OF CANADIAN ARMED FORCES

The first line of Canadian land defence was now the new dominion’s volunteer militia. Since the 1850s, the colonies had each, with strong British encouragement, begun to organize volunteer units that trained in the evenings and in summer camps, much like the reserve forces of today. In 1868, the militias in the former colonies were brought together under a new Department of Militia and Defence in Ottawa. This was the origin of the militia units in Nova Scotia and the Maritimes that came out on full-time service in the Halifax defences during the First World War. The main units at Halifax were two infantry battalions—the 63rd Regiment (Halifax Rifles), which had originally been raised as part of the pre-Confederation Nova Scotia Militia in 1860, and the 66th Regiment (Princess Louise Fusiliers), organized in 1869—and an artillery unit, the 1st (Halifax) Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery. The artillery regiment, although organized in 1869, had pre-Confederation roots in artillery units of the Nova Scotia Militia at Halifax that the British garrison had trained to help crew the fortress guns during the crises of the 1860s.8

Canada’s own regular army of full-time troops—called the “permanent force”—had modest beginnings. In 1871 the government organized two artillery batteries, one at Kingston, Ontario, and the other at Quebec City, which had been principal British army stations, to take over the fortifications from the departing British troops. The batteries, which included some expert British artillerymen who transferred to the Canadian service, also ran courses for the part-time militia, and sent instructors to assist the units. In 1883, the government also organized infantry schools (the origins of the Royal Canadian Regiment, which still serves today) and a cavalry school, all in Quebec and Ontario.

One of the most powerful instruments for economic development and nation building in the late nineteenth century was railways. Construction was immensely costly, and this was an inducement for New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, whose finances proved unequal to the challenge, to enter Confederation. There was large-scale railway development in the pre-Confederation province of Canada. However, the Atlantic terminal for the Grand Trunk, the main line, was Portland, Maine. It was much closer to Montreal and Quebec City than the Atlantic ports of the Maritime provinces, which could be reached only by the circuitous, difficult route along the south shore of the St. Lawrence and through the whole of New Brunswick’s interior. A large problem with the American terminus became apparent during the war scare with the United States in the winter of 1861–62, when the St. Lawrence was frozen. British Army reinforcements for the province of Canada had to disembark at Saint John, New Brunswick, and move overland on foot and by sleigh to Rimouski, the railhead on the St. Lawrence.

Britain had guaranteed a defence loan for the fortification of Montreal, Toronto, and Hamilton during another war scare with the Americans in 1865. In 1873, when tensions had eased, the British agreed to the Canadian proposal that the loan should instead be used for construction of the Intercolonial Railway between Rimouski and Halifax, a sounder investment for long-term security than fortifications in Quebec and Ontario. With the completion of the Intercolonial, in 1876, which incorporated the short lines in southern New Brunswick and central Nova Scotia those former colonies had managed to build before Confederation, Halifax and Saint John finally had an efficient land-route connection to the continent. It would prove invaluable in the First World War, not for the deployment of British Army reinforcements against American aggression, but for the dispatch of Canadian troops and munitions to support the Allied forces on the Western Front. Heavily damaged as the North End yard was in the explosion of December 1917, the railways brought early outside relief to the city while also carrying evacuees.

During the late 1880s, the British armed services began to improve defence preparations at the Empire’s naval ports in response to rapid developments in armaments. In contrast to the days of sail when approaching vessels could be seen hours or even days before their arrival, fast steam-powered cruisers could make surprise raids, inflicting grievous damage in a short time before disappearing as suddenly as they appeared. The latest long-range naval guns could bombard ships in harbour and port facilities with heavy explosive projectiles form a range of ten kilometres or more, while torpedo boats could rush into the port by night and launch self-propelled torpedoes. France and Russia, then the most likely hostile powers, were investing heavily in these technologies, and the United States was beginning to. The British modernized the forts at Halifax with the latest guns and newly developed electric searchlights, and drafted a detailed “defence scheme.” This document, which was updated annually and grew to 120 printed pages, laid out actions for every department of the command staff and every unit for the rapid mobilization of the fortress defences. These measures included the construction of entrenchments to cover possible landing points, expansion of the new telephone communication system, and the distribution of supplies and ammunition.

The British army garrison of about 18009 troops was sufficient to provide fewer than a sixth of the personnel required for defence in the worst-case scenario, a major combined naval and army assault from the United States. In the late 1880s, the British War Office arranged with the Canadian government to assign the Halifax militia units and other units in Nova Scotia to specific roles in the defence scheme. Every fall, the British garrison held a mobilization exercise in which the militia units participated. In 1900–1902, Canada, as part of its contribution to the war in South Africa, provided more than fifty per cent of the regular army garrison, comprising 1000 infantry specially recruited for full-time service, to allow the British battalion in garrison to go to the fighting front. This initiative foreshadowed the transfer of the fortress to Canadian control only a few years later.

The end of the British military and naval establishments at Halifax began in December 1904, when the British government announced the closure of the dockyard and the disbandment of the warship squadron assigned to the North America and West Indies station. This was the start of a revolution in British naval policy that at once endeavoured to cut the soaring defence expenditure while simultaneously strengthening the fleet. Money saved by closing overseas dockyards such as the one in Halifax, and by scrapping the mostly older warships employed on expensive overseas deployments, was used to build a smaller number of larger, faster warships. These would be based at Britain’s home ports at less cost than maintaining squadrons overseas, but the speed of the new ships would allow them rapidly to respond to emergencies in distant waters.

The Admiralty, however, insisted that the garrison and coastal fortifications should be maintained at Halifax. It continued to consider essential a secure base in the northwestern Atlantic so that British warships could again take up station in the event of a war that threatened Britain’s vital transatlantic shipping. This was why, in prolonged negotiations over the transfer of the naval dockyard to the Canadian government, the Admiralty insisted in the agreement concluded in 1909 that Royal Navy warships should continue to have the right of automatic access to the dockyard.

The British War Office faced financial straits of its own and, in 1904, asked Canada to provide part of the permanent army garrison that was to remain at Halifax. The Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, which had never been keen on joint Empire defence undertakings, startled the British by offering to provide the full garrison. In fact, for Laurier, it was a politically attractive proposition. Pro-Empire, largely English-speaking Canadians approved of this significant assistance to the mother country. Those opposed to military support for the Empire, notably in French Canada, were pleased to see the last British garrison leave the country.

CANADA TAKES OVER THE GARRISON AND DOCKYARD, 1905–1914

In 1905–6, the Canadian government expedited the departure of the British troops, while tripling the size of Canada’s small permanent force to 3000 troops, in order to provide a garrison of about 1200 regulars at Halifax. In taking over the fortress, the Canadian government made a commitment to the British to keep fully up to date both the fortifications and the defence scheme for the rapid provision of a full war garrison in the event of a crisis. This the Canadian government did. When the British garrison left, they had nearly completed a full modernization of the harbour forts with the latest guns and electric searchlights. Canada finished the work, and in the years before the outbreak of the First World War moved some of the gun and searchlight positions farther out the harbour to counter the increased range and speed of the latest warships. The Halifax militia units continued to train with the newly arrived Canadian regular troops, as they had with the British, so the militiamen would be ready instantly to assist the regulars in mobilizing the fortress in an emergency.

The transfer of the fortress to Canadian government control coincided with the creation of regional military commands in eastern Canada. These were commanded by senior officers of the permanent force, usually a brigadier-general or major-general; the staffs of professional personnel were needed to handle the administration, training, and war planning for the local individual units in the area. The new commands answered directly to Militia Headquarters at the Department of Militia and Defence in Ottawa, and were established in order to carry out the national plans and policies developed by the Ottawa headquarters.

Control of the Halifax fortress passed in 1905 to the commander of the new Maritime Provinces Command, which set up shop in Halifax in the facilities vacated by the British garrison staff. In 1911, the Maritime Provinces Command was renamed the 6th Division, and in 1916 again re-designated as Military District No. 6. It was this headquarters, proven in the challenges of war mobilization since 1914, that immediately came to the assistance of Halifax’s municipal government during the 1917 disaster, and coordinated the substantial help available from the large British and American warships in port.

The success of the Canadian Militia (as the Canadian army was officially known until 1940) in running the Halifax fortress stood in contrast to the troubles of the newly established Canadian navy. The issue of a navy for Canada had long been on the back burner in national politics. In 1868, the new federal government had established the Department of Marine and Fisheries, whose resources included a small fleet of steamers. Their duties included “protection” patrols of the fishing banks to enforce Canadian and international regulations, the transport of supplies to lighthouses and life-saving stations, and the maintenance of buoys and other aids to navigation. This seemed to be all the navy Canada needed until 1909, when expansion of the German navy sparked a panic in Britain and all through the Empire. Britain’s post-1904 policy of building fewer but bigger and more sophisticated warships had resulted in the launching of the powerful battleship HMS Dreadnought in 1905, which had instantly become the new benchmark for national naval power.

The news that Germany might out-build Britain in this key type of warship brought popular demands in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada that the dominions should assist by making special cash grants to the British government to expand British battleship construction. The Admiralty responded that it would be more helpful if the dominions now built their own navies—each of which should include a new major warship type, the fast battlecruiser. These were massive warships of 20,000 tonnes that had the heavy gun armament of a dreadnought but less armour and higher speed, and up to 1000 crew. The Laurier government agreed that the time had come for Canada to have its own navy, but got the Admiralty’s agreement that it should be limited to smaller warships better suited to Canada’s immediate needs. These included four cruisers—the smallest major seagoing warship type, of about 5000 tonnes and with a crew of about 400—that could protect shipping offshore, in which role they would also be capable of helping British squadrons on the high seas. The remaining vessels would be six smaller destroyers for the defence of Canada’s own coasts and ports, especially Halifax. Destroyers displaced only about 1000 tonnes with a crew of seventy, but had a powerful armament of torpedoes and were very fast (up to 36 knots, or 60 kilometers per hour), which made them ideal for rapidly responding to intelligence of any suspicious approaching vessels.10

The Laurier government founded the Royal Canadian Navy in 1910 on the basis of this plan and immediately purchased two British cruisers, the small Rainbow of 3300 tonnes for the Pacific coast and the much larger Niobe of 10,000 tonnes for the Atlantic coast. These were to serve as training vessels for Canadian recruits while the modern cruisers and destroyers were built. Immediately, the naval scheme ran into political trouble. French Canadians believed that any dominion fleet would in fact just serve as part of the Royal Navy and implicate Canadians in every British war; English Canadians derided the “tin-pot navy” as too small to be of use in helping Britain.

The unpopularity of the navy contributed to the Laurier government’s defeat by Robert Borden’s Conservative party in the federal election of September 1911. Borden cancelled the building of modern warships and cut the navy budget to subsistence level. The government turned a blind eye as Canadian recruits deserted, and did not renew the contracts of the Royal Navy crews of Niobe and Rainbow who had been engaged to operate the ships as training schools for Canadian seamen. Borden’s alternative plan of giving a large cash contribution to the British government to build three of the latest “super-dreadnought” battleships was defeated by the Liberal majority in the Senate in May 1913.

Both cruisers had to be laid up as the strength of the RCN dwindled—to about 300 personnel by 1914. Niobe’s complement alone was 700 personnel. On the east coast all that the few personnel remaining could do was work with the army garrison at Halifax to develop the most basic naval parts of the defence scheme, using small lightly armed steamers from the Fisheries Protection Service. The administration of these vessels had been transferred from the Department of Marine and Fisheries to the navy and, in the absence of anything better, the steamers would be employed for harbour and coastal defence in the event of war.

WAR, 1914

When in late July 1914 telegrams began to arrive from London prescribing precautionary defence measures, Halifax was ready. By the time the telegram that announced Britain and the Empire were at war with Germany arrived at midnight 4–5 August 1914, the forts were crewed by regular troops and the city militia units, and infantry outposts were in place to guard important facilities and cover areas around the outer harbour where enemy agents or armed parties might attempt to slip ashore.

One of the key precautionary measures, brought into effect at midnight 1–2 August and continued throughout the war, was the “examination service” at the entrance to the harbour to verify the identity and cargo of incoming ships. It was intended to guard against the entry of disguised enemy vessels that might carry hidden torpedoes or other armaments, or be rigged as floating bombs, to destroy shipping and port facilities (tragically, the very menace that Mont-Blanc proved, unintentionally, to be). Incoming merchant ships had to report to the “examination vessel,” a small steamer from the government’s civilian marine fleet operated by the navy, stationed in the harbour channel off Fort McNab at the south end of McNabs Island, the furthest seaward of the coastal batteries. The fort’s armament included a heavy 9.2-inch gun that could fire a 360-pound (163-kilogram) shell to a range of fifteen kilometres, and two quick-firing 6-inch guns each of which fired a 100-pound (45-kilogram) shell to a range of about ten kilometres.

The waters off Fort McNab were designated the “examination anchorage,” where incoming ships were to wait for clearance or, once cleared, for entry into the port if it was closed. Incoming ships were to present their papers to the crew of the examination vessel, who would inspect the ship if anything seemed suspicious. If the ship failed to stop, or began to move before it was cleared, the guns at Fort McNab were ready to fire first a warning shot across the bow of the vessel, and then for effect. Powerful searchlights on the shore, controlled from Fort McNab’s command post, could be quickly exposed in the event of vessels trying to slip into port under cover of darkness. Once a ship was cleared for entry, the examination vessel sent a signal with her identity and cargo to the chief examination officer, a senior member of the staff in the naval dockyard on the Halifax Narrows. The chief examination officer had authority over all movements of ships within the port; in wartime he took over most of the powers exercised by the King’s harbourmaster, in peacetime a civilian government official.

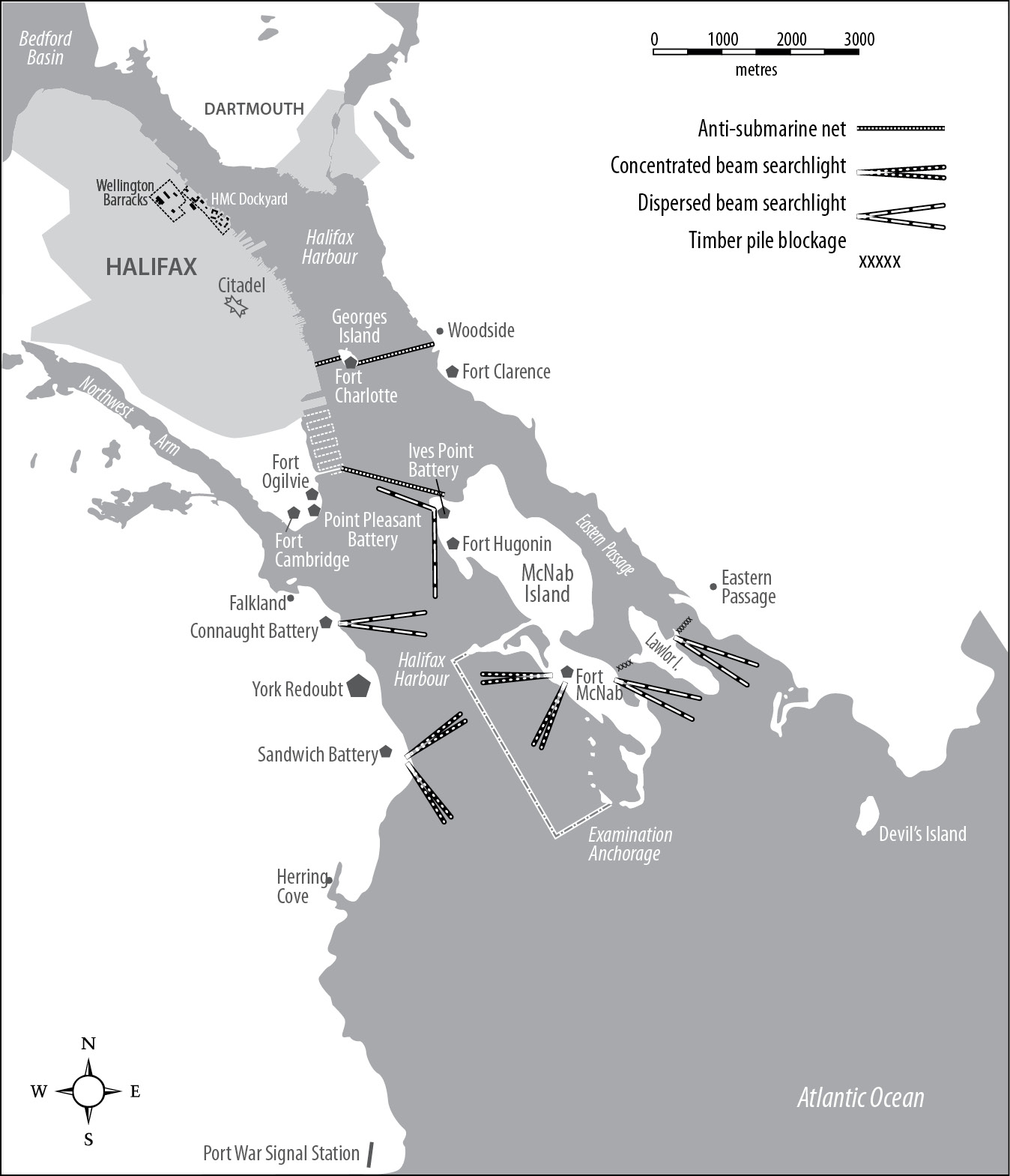

MAP 1 | Halifax harbour circa 1917. Map ©Roger Sarty.

During the precautionary period in late July and early August, two British cruisers from Bermuda arrived in Canadian waters in response to reports that German fast cruisers were headed there. This was a threat the Admiralty took seriously: the British economy depended on seaborne trade, and much of it came from the Americas via the short north Atlantic Great Circle route that passed close by Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. Additional cruisers and armed merchant cruisers (fast merchant ships, often passenger liners, commissioned into the navy and fitted with guns) came from Britain and began to operate from Halifax. The Royal Navy operated five or six cruisers and armed merchant cruisers from Halifax for the rest of the war.

The Admiralty, in the 1904 cutbacks, had retained Bermuda as the Royal Navy’s main operating base in the Americas, but it became clear in 1914 that Halifax was at least as important because of its position on the northern trade routes—especially so because of the United States’ declared neutrality in the European war. German merchant ships, unable to return home because of the Royal Navy’s strength in the North Sea and eastern Atlantic, headed to US ports to intern themselves and thus avoid capture. These vessels posed another threat to the northern routes, as some of the German ships, especially the large passenger liners, were, as British intelligence knew, outfitted to take on armament and operate as raiders. All they had to do was slip out of port and meet a German warship to take on guns and ammunition.

Thus, the main commitment of the half-dozen Royal Navy cruisers and armed merchant cruisers that worked regularly from Halifax was to maintain patrols off US ports, especially New York, where there were thirty-eight self-interned German vessels. In September 1914, the British squadron was reinforced by HMCS Niobe, which was able to get to sea with key personnel provided by Britain, including experienced seamen from the Newfoundland Royal Navy Reserve, a training organization the Royal Navy had established to give military training in the offseason to Newfoundland fishermen. Canadian volunteers completed the crew. Most were enlisted in a new branch of the service, the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve, the name indicating the Borden government’s policy that any Canadian naval effort should more directly support the Royal Navy than Laurier’s scheme.11 Niobe, which the Borden government placed under Admiralty control, joined the watch off US ports.

By the spring of 1915, the Royal Navy had swept the German navy and merchant shipping from the high seas. On the diplomatic front, Britain was tightening the economic blockade to prevent an increasingly wide range of goods from reaching the Central Powers in neutral shipping. Germany responded by declaring its own blockade of Britain, allowing submarines (U-boats) to sink on sight any ship approaching the British Isles. Allied shipping losses soared. The most dramatic attack was U-20’s sinking by torpedo of the liner RMS Lusitania in May 1915. She went down with 1500 passengers and crew near the large Royal Navy base at Queenstown, Ireland—in supposedly well-defended waters.

The Lusitania disaster caused shock waves in Ottawa. There were reports (false, as it proved) that U-boats were crossing to North American waters. Most of the big ocean transports that carried Canadian troops to Britain departed from Quebec City or Montreal, and sailed some 1100 kilometres through the entirely unprotected Gulf of St. Lawrence, waters in which surface vessels were particularly vulnerable to submarine attack. Cruisers, like those operating from Halifax, were vulnerable themselves. The best anti-submarine warships were fast, manoeuvrable destroyers, but the Canadian government’s appeals to Britain got the chilling response that none could be spared from the pitched struggle in European waters. Canada would have to make its own arrangements. Fortunately, U-boats lacked the range to make a return trip to North America without refuelling, which could be achieved only by linking up with a disguised supply vessel, or German agents from the neutral United States who might deliver fuel to one of the many remote bays along the coast. The immediate need was only for lightly armed vessels that could keep watch and investigate reports of suspicious activity.

In July 1915, the Canadian navy established the St. Lawrence Patrol to keep watch on these vulnerable waters. It was a modest undertaking. The base was a rented commercial wharf at Sydney, on Cape Breton Island, and the seven vessels assigned included civil government steamers, chartered civilian vessels, and two large yachts surreptitiously purchased in the United States, whose neutrality laws forbade the sale of marine craft to combatant navies. Some of the personnel in the civilian crews transferred to the navy and the rest came from HMCS Niobe. She had just returned from what would prove to be her last patrol and needed a major refit. The British offered another cruiser to replace her, but the Canadian government refused in view of the more urgent need for anti-submarine defences. Niobe was permanently moored at the naval dockyard at Halifax; her large hull provided an immediate solution to the severe shortage of barracks and office accommodation to sustain the service’s expanding wartime role.

To secure the harbour against close-in submarine attack, the navy installed a wire-cable anti-submarine net, suspended on a series of floats on the surface and descending to anchors on the floor of the harbour, from the Dartmouth shore to Georges Island, and then from Georges Island to the Halifax waterfront. The central section of the net in the main shipping channel was moored so that one end could be swung open by a small “gate vessel” to allow the movement of vessels in and out of port. The net and the whole of the entrance to the inner port, extending several kilometres to the south, could be brilliantly illuminated at night by ten “dispersed beam” searchlights. Unlike the narrow-beam, long-range searchlights at the outer forts that swept the approaches to track suspicious vessels for engagement with long-range fire, the dispersed-beam lights projected wide fans of light on fixed bearings. This broad illuminated zone enabled the quick-fire gun batteries on Georges Island, the northern tip of McNabs Island, Point Pleasant, and a new battery under construction at Falkland Cove on the western side of the harbour, to smother one or several craft attempting to rush into the port. Thus, the net would frustrate an underwater attack, while the gun batteries and searchlights would counter a fast surface run by submarines attempting to fire torpedoes and their deck guns into the port, or to lay mines—an attack most likely to come under cover of darkness.12

The German submarine offensive also turned Halifax into the main port for the transport of troops overseas. Quebec City and Montreal were the principal embarkation ports for the first two contingents of troops in 1914 and the first half of 1915. Then starting in August 1915 most sailed from Halifax, a total of more than 284,000 troops by mid-1918, about two-thirds of the 425,000 Canadian soldiers who went overseas during the war.13

THE GERMAN SUBMARINE OFFENSIVE AND CONVOYS, 1917

The Germans abandoned the “sink on sight” policy in the fall of 1915 in response to protests from the United States, but became more aggressive a year later in an effort to reverse the bloody stalemate of the land war in France and Belgium. One new venture highlighted Canada’s vulnerability. Early in November 1916, the submarine U-53 appeared at the US naval base at Providence, Rhode Island, showed off its powerful engines and weapons to US naval officers, and refused her right at a neutral port to receive enough fuel to return home. She then patrolled off Nantucket Island, a single day’s cruise south of Nova Scotia, and sank five British merchant ships. This dramatic evidence that the German submarines were now capable of transatlantic operations brought new demands from the Canadian government that the Royal Navy provide anti-submarine warships for Halifax and the east coast. Then, on 1 February 1917, the German government proclaimed a new campaign of “sink on sight” and, now with additional U-boats in service, inflicted still heavier merchant ship losses than in 1915. Far from being able to help Canada, Britain needed help: unless defences in the eastern Atlantic were greatly strengthened, the Allies would have to curtail land operations for the want of supplies. All that Canadian shipyards could produce on an emergency basis was modest fishing-type vessels modified in design by the Admiralty to carry basic anti-submarine armament. Canada ordered the construction of twelve steel anti-submarine trawlers from shipyards on the St. Lawrence and in the Great Lakes. The British placed their own orders in Canadian shipyards for thirty-six trawlers and sixty still smaller wooden “drifters.” The British plan was to use most of the vessels to augment its own anti-submarine patrols and to allocate some to help Canada build up its defences. (In 1918, when U-boats began sustained operations in North American waters, the British in fact turned most of the vessels over to the Canadian navy.) The first of the new vessels from the Canadian and British contracts were completed in the fall of 1917, and a few reached Halifax before the explosion.

Meanwhile, on British advice, during the spring of 1917 the Canadian navy installed an additional anti-submarine net at Halifax. It ran between the northern tip of McNabs Island and the breakwater at the new ocean terminals under construction near Point Pleasant Park at the south end of the city. This location was something more than two kilometres seaward (south) of the existing net at Georges Island, and was intended to keep an attacking U-boat well out of torpedo range of the inner harbour.

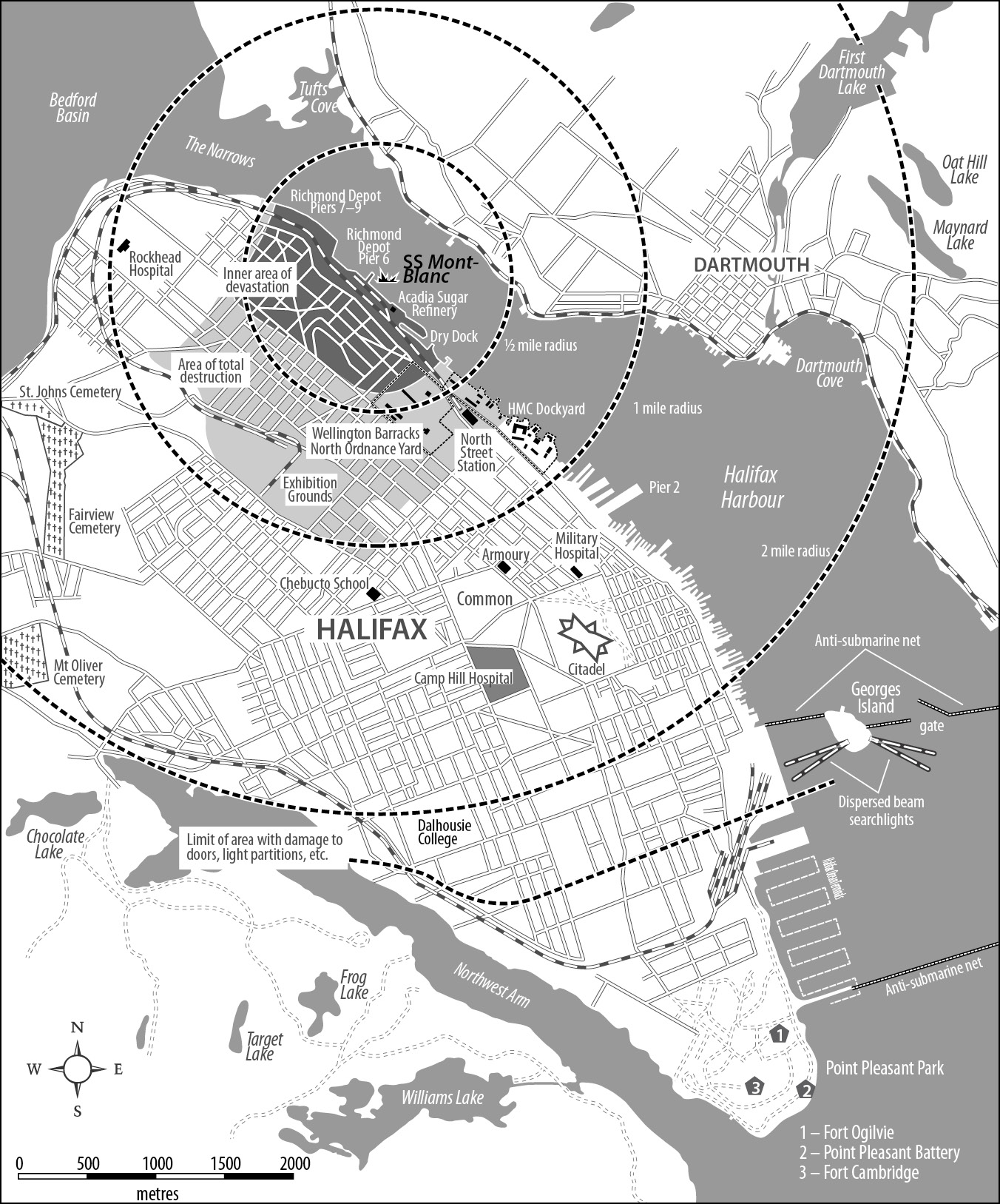

MAP 2 | Halifax inner harbour circa 1917. Map ©Roger Sarty.

Halifax immediately felt the effects of the new German offensive in early 1917 with an influx of merchant vessels. In late April, there were forty-nine ships moored in Bedford Basin. They came as a result of new British measures to ensure that ships destined for neutral countries in Europe were not carrying supplies for the Central Powers. This was an essential part of the economic blockade of the enemy states, designed to drain their resources for military operations. Previously these ships had to put into a British port before and after a visit to a neutral port for special examination by expert Royal Navy personnel. In February 1917, however, the British government designated Halifax as an examination port, so the ships could be cleared there and face less risk of attack in the new submarine offensive, whose main strength was in the approaches to British ports. Early in March 1917, a Naval Control and Examination Staff under the command of Captain Oscar M. Makins, a retired officer who had returned for war service, arrived in Halifax. The Canadian navy arranged the assignments of the patrol vessels and government steamers at Halifax so that one of these vessels was always stationed as a guard ship near the entrance to Bedford Basin to ensure no merchant ship under examination departed until it had been cleared.14 On 6 December 1917, HMCS Acadia, the government hydrographic survey ship that had been commissioned into the navy for coastal patrol, was carrying out this duty.

Many of the merchant vessels that came in for examination were operating for “Belgian Relief.” The tightening of the Allied economic blockade of the Central Powers threatened a humanitarian crisis for the population of German-occupied Belgium. It was in the interests of the Germans, who were responsible for that population, to allow the entry of food and other supplies. The Germans agreed not to attack the vessels, from Allied as well as neutral countries, assigned to carry these goods. Most of the supplies came from Canada and the United States, and the ships now put into Halifax for examination before their departure for Europe and after their return to ensure they did not carry anything that might help the enemy.15

Halifax became still more important to the Allied war effort as a result of the British decision to sail transatlantic shipping in defended convoys in a desperate measure to reduce losses to submarines. Troopships from Halifax had in fact sailed in small convoys—two or three ships, usually, under the escort of one of the cruisers based at Halifax—since early 1916, when a powerful German surface raider, Mowe, got loose in the Atlantic. What the Admiralty attempted in the spring of 1917 was much more ambitious: to sail twenty or more standard merchant ships together. The first convoys sailed from Hampton, Virginia, and then New York, which was possible because the US entered the war on 6 April 1917. In July, shipping from Canada, mostly from the St. Lawrence, began to assemble into convoys at Sydney, Nova Scotia, designated “HS,” the acronym of “Homeward from Sydney.”

Convoys proved to be an extremely effective counter to the submarine threat. Merchant ships sailing separately created a stream of undefended targets for U-boats. With so many ships at sea, it was possible for the U-boat to find a good number of them, and then attack each in turn with little danger of defending forces reaching the scene in time. It soon became apparent that twenty or even fifty ships sailing together in a single group could not be sighted out on the broad ocean much more easily than a single vessel, so that the submariners had only one chance to find a target instead of the many presented by ships sailing alone. Moreover, a single group of ships could be speedily switched to a new course in response to intelligence that a submarine might be hunting near the original course. From the perspective of the submarine commanders the ocean suddenly became empty. Even if the submarine was able to find a convoy, there was only one chance to attack, and a risky one as escorting warships were present. The big difficulty from the Allied perspective was that merchant ships were greatly delayed by having to wait for convoys to assemble, and then by being able to proceed only at the speed of the slowest ship. In the summer of 1917, therefore, the Admiralty reorganized the system so that convoys were made up of ships of similar speed. Sydney was designated for slow convoys, 7 knots (13 kilometres per hour) or less, and slow ships now gathered there from US as well as Canadian ports. In August 1917, fast merchant ships began to join the small troop transport convoys from Halifax, and these were now designated “HX” (Homeward from Halifax).

In November 1917, the assembly of HS convoys, and the ships and headquarters of the RCN’s St. Lawrence patrol, moved from Sydney to Halifax in anticipation of the often violent winter storms and then freeze-up of the St. Lawrence. This was why Mont-Blanc, after loading with explosives in New York, came to Halifax to join a slow convoy in early December—she was too slow for the medium- and fast-speed convoys that assembled at New York.

THE NAVAL ESTABLISHMENT IN 1917

All the convoys that sailed from Canadian and US ports were organized by British “port convoy officers.” The port convoy officer at Sydney, Rear-Admiral Bertram M. Chambers, Royal Navy, moved with his staff to offices rented in the Metropole building on Hollis Street, in the south end of the city two blocks from the waterfront. Chambers directed the operations of the British and US cruisers that escorted the convoys across the Atlantic, and controlled the assignment of merchant ships to convoys, but had no authority over Canadian naval establishments and ships. Still, he was the most senior officer at Halifax, outranking all of the Canadian naval officers, as well as the captains of the US warships that now regularly put into Halifax. Aside from the weight of his flag rank, he was experienced and capable. Born in 1866, he had joined the Royal Navy in 1879, and in his varied career had filled senior appointments in the newly organized Royal Australian Navy in 1911–14, before returning home to command two cruisers, HMS Illustrious and then HMS Roxburgh in 1914–15. He later became the convoy officer at Scapa Flow, the Royal Navy’s main wartime base in the Orkney Islands—excellent experience for the appointment in Canada. He worked well with the RCN, upon which he depended for communications services, and to ensure that vessels assigned to convoy were fuelled and provisioned in time for sailing. After he moved to Halifax, he also assumed responsibility for the sailing of the fast HX convoys, with the detailed arrangements continuing to be made, as in the past, by the RCN staff at Halifax.16 One of Chambers’s assistants was a Canadian, Lieutenant-Commander James A. Murray, Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve. An older officer, at fifty-seven, he was an extremely experienced merchant captain; his commands included the Canadian Pacific liner Empress of Britain.17

The most senior Canadian officer normally at Halifax was Captain E.H. Martin, superintendent of the dockyard.18 A former Royal Navy officer, he had held his captaincy since the founding of the RCN in 1910. From November 1917 to January 1918, however, he was in London, consulting the Admiralty about anti-submarine defence measures for the Canadian coast. Acting in his place was Captain Frederick C.C. Pasco, fifty-five years of age, a Royal Navy officer who had retired in 1914 after thirty-eight years’ service, much of it in hydrographic survey (mapping) work in the far reaches of the Pacific. In 1915, he accepted Canadian employment to command the new St. Lawrence Patrol. Since August 1917, the patrol flotilla had been commanded by acting Captain Walter Hose, forty-three, a Royal Navy officer who had been seconded to command HMCS Rainbow at Esquimalt, B.C., in 1911, and then transferred to the Royal Canadian Navy. He had won the confidence of his superiors by capably managing the resource-starved west coast establishment in difficult circumstances.19

FIGURE INTRO.1 | Rear-Admiral Bertram M. Chambers, in 1919, the British officer who organized convoys at Halifax: “Order was already beginning to arise out of chaos.” National Portrait Gallery, London, by Walter Stoneman, x66574.

The naval facilities at Halifax were modest. The dockyard was a strip of land that extended about 800 metres along the shore of the Narrows where it had been established in 1758. During the latter part of the nineteenth century it had been hedged in on the west by the main line of the railway. There were four principal wharves, large sheds for coal storage, other storehouses for marine gear and armament, and workshops. According to the official history of the navy, “it was reasonably complete and well-constructed plant, whose equipment, however, was largely obsolescent,”20 and, it should be added, the dockyard was far too small. During the nineteenth century the Royal Navy had improved the facilities only to the extent necessary to support the ships that came north each spring from Bermuda, the Royal Navy’s main dockyard in North America. The shortage of accommodation was one reason why the navy laid up Niobe as a floating barracks and office complex in 1915.

FIGURE INTRO.2 | Captain Walter Hose, RCN, on board HMCS Rainbow in 1914, became the senior Canadian naval officer at Halifax when his superior was injured in the explosion. George Metcalf Archival Collection, Canadian War Museum, CWM 20020045-2810.

There were some 1000 personnel living aboard the cruiser in December 1917. These included personnel undergoing training to crew the new anti-submarine vessels being built in the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes yards. There were also radio personnel under training for a program requested by the Admiralty to provide naval operators for equipment being installed in merchant ships carrying war supplies. Operators were needed as well for the government coastal radio stations, established for marine safety, that the Department of the Naval Service took over from the Department of Marine and Fisheries in 1910. Additional coastal stations had been built during the war to assure dependable communications with warships at sea and with the headquarters of the North America and West Indies station in Bermuda. The naval wireless network included a station at Camperdown on a high hill near Portuguese Cove, overlooking the western headland of Halifax harbour and the main ocean approaches to the port. This was the Port War Signal Station, which had a tall mast for naval visual signalling flags. The station’s purpose was immediately to communicate with any approaching warship, and give early warning to the port defences either to stand down to allow a friendly warship rapid entry into the security of the harbour or, alternatively, to raise the alert for action against a possible enemy.21

Also in Niobe was the office of Commander Frederick Evan Wyatt, the chief examining officer (CXO). He was responsible for the examination service off McNabs Island, the opening and closing of the gates in the anti-submarine nets, and control of marine traffic within the harbour. Wyatt was an experienced merchant ship captain and, like many merchant marine officers, a member of the Royal Naval Reserve. He was one of the British officers provided by the Royal Navy to get Niobe to sea in August 1914, and he remained until she was laid up in 1915. Wyatt applied to continue to serve in Canada and Captain Martin selected him for the CXO appointment.22

At the north end of the dockyard was the former naval hospital, which had been converted to house the Royal Naval College of Canada, one of the few initiatives of 1910 not shut down by the Borden government. An instructional staff under Lieutenant-Commander Edward A.E. Nixon, a Royal Navy officer who had transferred to the RCN, presided over thirty-eight cadets in December 1917. The college had been intended to raise Canada’s own naval officer corps, but, with the cutbacks after Borden’s election, there were no Canadian warships operating in which the cadets could complete their training and no prospects for career advancement. Graduates were thus assigned to British warships and continued their service in the Royal Navy. Most gained their sea legs in British fighting ships in the European war zone. The small vessels the RCN began to acquire in 1915 for local anti-submarine patrols were not suitable for the development of well-rounded young officers. Thus, the Canadian vessels drew their key personnel from experienced seamen in the government marine services (the crews of the vessels commissioned in the RCN in many cases transferred to the navy), the merchant marine, and, throughout the war, from the Newfoundland Royal Naval Reserve.

West of the former naval hospital, on the hill beyond the railway tracks, was Admiralty House, the former residence of the British admiral commanding the North America and West Indies station. (This handsome stone building still stands in HMCS Stadacona, now part of Canadian Forces Base Halifax and the present-day barracks and training centre for the Atlantic fleet.) It was converted into a naval hospital to meet the greatly increased activity during the First World War, but was damaged in the explosion, and its equipment used in other emergency facilities.23

Adjoining the naval college grounds to the north on the waterfront was the North Ordnance Yard, a cramped installation that included a heavy stone magazine for the storage of ammunition for both the army garrison and navy. Late-nineteenth-century railway construction went through the ordnance grounds, cutting them off them from the adjoining Wellington Barracks immediately to the west (next to Admiralty House), and isolating the westernmost magazine. The latter was thus used to store small-arms ammunition for the infantry battalion in the barracks nearby, while the main magazine buildings on the waterfront to the east of the railway tracks remained the repository for artillery ammunition. The encroachment of the city around the site, and especially the close proximity of locomotives spewing hot cinders, had long been a source of concern to the military.24 An apparent fire in the small-arms magazine near Wellington Barracks after the explosion on 6 December 1917 caused an alarm and partial evacuation of the North End by survivors, while the damage to the main artillery magazine necessitated a large emergency effort by naval and military personnel to remove the many shells. Not until the 1920s would the government fund the establishment of a joint services magazine on a large site on the eastern shore of Bedford Basin. (The magazine is still in use by the Canadian Forces.)

Immediately to the north of the magazine was the Halifax Graving Company’s large concrete dry dock. It had been built between 1886 and 1889 with subsidies from the Canadian government, which was interested in economic development, and the British Admiralty, which promoted the building of dry docks at strategic points throughout the Empire that would be available to the Royal Navy. The funding came with the requirement for construction on a substantial scale—a length of 173 metres—to be able to accommodate the largest vessels of the day. It was the major ship-repair facility in the port and, rebuilt after its surface plant was demolished in the explosion, is still in service as part of the Halifax Shipyard of Irving Shipbuilding.25

THE GARRISON IN 1917

The army’s senior officer was Major-General Thomas Benson, who wore two hats as general officer commanding Military District No. 626 and the Halifax fortress commander. Born in 1860, Benson had graduated from the Royal Military College of Canada in 1883, joined the permanent force artillery, and rose through virtually all of the command appointments in that branch of service. In 1913 he became master-general of the ordnance, responsible for much of the equipment of the Canadian army, and a member of the Militia Council, the senior administrative body of the army, before he moved to Halifax in November 1915.27

His senior staff officer, the assistant adjutant general, was Colonel William Ernest Thompson, a local militia officer with the Halifax Rifles. Age fifty-two, Thompson was a lawyer in civilian life and came out on active duty with his regiment in August 1914; he was moved to the headquarters in December of that year because of his administrative abilities.28 Another officer who would play an important role in responding to the explosion was Lieutenant-Colonel F. McKelvey Bell, age thirty-nine, the senior medical officer, with the appointment assistant director medical services, MD No. 6. Bell was an Ottawa surgeon and had joined the pre-war militia. In August 1914 he volunteered for overseas service and went to France in 1915 with the No. 2 Canadian Stationary Hospital. He returned to Canada in 1916 to become deputy director of medical services at headquarters in Ottawa. He moved to Halifax in the spring of 1917.29 The main army headquarters offices were in the old British headquarters at the east end of Spring Garden Road and in the modern Dennis Building on Granville Street a few blocks away, in the south end of the city and thus sheltered from the main blast of the explosion. Thus, the key members of the army command staff escaped injury.

FIGURE INTRO.3 | Major-General Thomas Benson (front, middle), the army commander in Halifax, with his staff. Benson and these officers directed the army’s large and effective relief effort, and enabled the relief parties from outside the city quickly to get into operation. From M.S. Hunt, Nova Scotia’s Part in the Great War, NS Veteran Publishing Co. Ltd., 1920. (Outside of copyright.)

The one complete report of the number of troops at Halifax in the militia department records of the explosion shows a total of 4944 personnel.30 These included 3292 from the active militia called out for home defence service to garrison the fortress. The militia was liable only for service in Canada, and for that reason in August 1914 the government had created a new army, the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), for men who volunteered to serve overseas. There were 1327 members of the CEF at Halifax, most of whom were training in preparation for transport overseas. Finally, there were 325 members of the British Expeditionary Force, mostly British residents of the United States who had elected to join the British rather than the Canadian or US forces.

More than 2000 of the militia garrison troops were in the forts and infantry defences on the outer harbour, in the Citadel, or barracks in the southern part of the city. These troops included the permanent force and militia artillery units, a total of 826 personnel, that crewed the forts, together with 200 members or more of the militia and permanent force military engineers, who operated the electric searchlights and telephone communications. The Halifax Rifles (541 personnel) were responsible for the infantry defences on the east side of the harbour, and their main camp was on McNabs Island. The Princess Louise Fusiliers (459 personnel), who provided the infantry defences on the west side of the harbour, had their headquarters and main barracks at the old fort at York Redoubt, across the harbour entrance from the southern part of McNabs Island. The bulk of the CEF and all the BEF troops were in huts on the Commons, and carried out training at the large stone armouries immediately to the north of the Commons.

The main garrison facility in the North End was Wellington Barracks, home to about 1000 troops.31 The principal tenant was the Composite Battalion, whose 471 personnel came from Nova Scotia militia battalions outside of Halifax, and provided guards at important facilities throughout the city, especially along the waterfront. The unit was assisted by No. 6 Special Service Company, CEF, with 209 personnel. They were members of the CEF (including men returned from overseas) who because of injury or illness no longer met the medical standards for front-line service but were fit enough for garrison duty. The other major occupant of Wellington Barracks was a training depot for CEF recruits for the Army Medical Corps, with a total strength in early December 1917 of 200 personnel.

A notable feature of the garrison was the large medical establishment. The station hospital built by the British garrison on Cogswell Street near Citadel Hill had by 1917 been expanded from its original capacity of 75 beds to 338 by internal renovations and the use of nearby buildings. A particular need was for treatment of patients with infectious diseases, including venereal diseases, and the militia department took over the civilian isolation hospital at Rockhead, at the northern end of the Halifax peninsula overlooking Bedford Basin. There were 93 beds in that facility by 1917.32

Much larger requirements arose as a result of the port’s service as the main terminal for troopships. Vessels coming back from Britain brought increasing numbers of seriously ill or injured personnel. The government created the Military Hospitals Commission in June 1915, initially to coordinate care by volunteer agencies, which proved unequal to the growing need. The commission thus began to employ staff from the Canadian Army Medical Corps and greatly expand its facilities. In early 1917, the commission took over buildings at the Presbyterian seminary at Pine Hill, in the south end of the city, where there were 150 beds for convalescents. On the waterfront, the commission fitted a large concrete building on Pier 2, the reception facility for immigrants at the deep-water terminal for large passenger ships, as a receiving hospital with 550 beds. Disembarked patients stayed for a week or two while their cases were reviewed and arrangements made to send them to the most suitable long-term care facilities across the country. The commission then built a 300-bed convalescent hospital at Camp Hill to the west of the Commons (between Robie Street and Bell Road), which opened in the fall of 1917.33

The December 1917 troop strength returns for Halifax show some 450 Canadian Army Medical Corps personnel. These included the staff and trainees of the CEF Army Medical Corps Training Depot at Wellington Barracks and a reinforcement draft of medical personnel who were awaiting transport overseas. The figures for the actual garrison, however, include mainly the “other ranks” support personnel, and not doctors and nursing sisters. According to the report of the disaster medical relief committee, there were thirty-seven CAMC doctors and fifty-five nursing sisters in the city on the morning of 6 December.34 That would give a grand total of well over 500 army medical personnel. Most important, the experienced medical staff in Halifax, capably led by Lieutenant-Colonel Bell, immediately took control of all the military medical personnel and facilities, and coordinated their employment with provincial and municipal hospitals for the emergency treatment of casualties.

Roger Sarty

Professor, Department of History

Wilfrid Laurier University