I

THE ABBOT FROM LANGRES

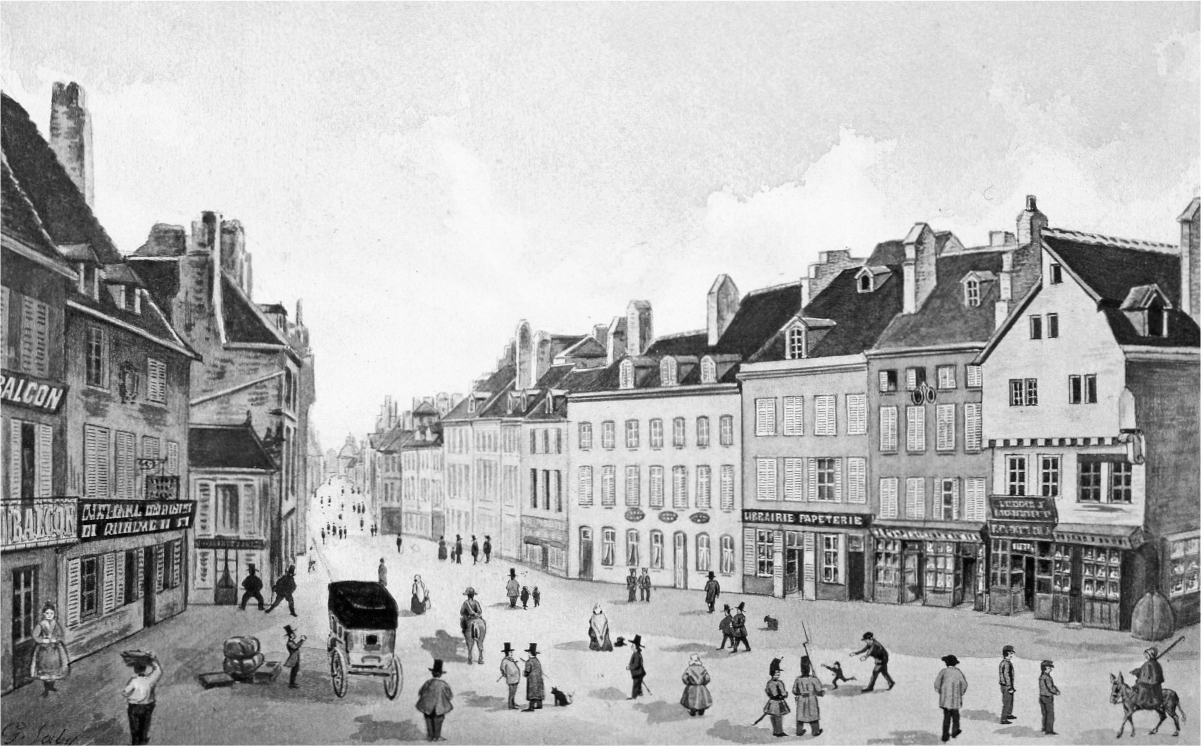

Perched between Franche-Comté, Lorraine, and Burgundy, the mile-square city of Langres is concealed by stone ramparts that rise 550 meters from the valley below. For more than two thousand years, pedestrians, horse-drawn coaches, and now cars have reached this fortresslike burg by climbing steep roads toward one of the city’s stone gates. Within minutes of passing through any of these posterns, one arrives at a triangular plaza that used to be called the place Chambeau. It was here that Denis Diderot was born to his parents, Didier and Angélique, on October 5, 1713.

Langres’s central square retains much of the feel of the eighteenth century. Virtually all of the city’s two-, three-, and four-story limestone houses are seemingly unchanged, though now some sag at the beams with age.1 As is often the case in old French cities, the most noteworthy shifts in this neighborhood have been symbolic. In 1789, the Revolutionary government redubbed the place Chambeau the “place de la Révolution,” a name it maintained until the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in 1814. The next emblematic change took place seventy years later, on August 3, 1884, when Jean-Ernest Darbot, mayor of Langres, rebaptized the square as the “place Diderot” in honor of the city’s most famous son.

THE PLACE CHAMBEAU, LANGRES, c. 1840

The ceremony organized in the writer’s honor garnered more international press coverage than Langres has ever received, either before or since. According to numerous reports, Darbot had the city festooned with paper lanterns and streamers.2 He and the city council also arranged for gymnastics demonstrations, shooting contests, and a marching band that played throughout the day, its fanfares melding with the din of twenty thousand celebrators.3 The highlight of the day, however, was the unveiling of the bronze statue of Denis Diderot designed by the celebrated creator of the Statue of Liberty, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. The sculptor depicted Diderot in a dressing gown and an insouciantly buttoned waistcoat. Looking out over the square from atop a marble pedestal, Diderot turns his head to his right, as if in the middle of a thought. Like Bartholdi’s massive Lady Liberty, which was under construction at that very moment back in Paris, Diderot clutches a book in his left hand.4

Journalists reported that the crush of people on the newly christened place Diderot called out a jubilant “Vive la république!” when they first spied the statue. A smaller group of observant Catholics looked on glumly from the edges of the crowd. What an outrage the whole event had been from their point of view: in addition to the fact that Darbot and the other republican politicians of Langres had scheduled the event on a Sunday, the city’s workers had also positioned the statue so that Diderot was conspicuously turning his back on Langres’s most famous religious icon, the nearby Saint-Mammès Cathedral.

STATUE OF DIDEROT IN LANGRES

Some 135 years after Darbot unveiled Bartholdi’s statue, the city’s atmosphere remains thick with memories of the writer. The place Diderot leads to the rue Diderot, which, in turn, leads to the collège Diderot, the city’s junior high school. Every third or fourth shop within the walled city also seems to display the name of its most famous son. In addition to a beautifully executed new museum dedicated to the philosophe, there is a Diderot café, a Diderot coffee bean shop, a boulangerie Diderot, a Diderot cigarette and cigar store, a Diderot motorcycle dealership, and a Diderot driving school. The town’s Freemasons, according to someone I met at a café in Langres, attend monthly meetings at the Diderot Lodge.

THE HOUSE WHERE DIDEROT WAS BORN

More important, however, are the early-modern buildings, houses, and churches that Diderot knew during his lifetime. Today, one can still stand in front of the chalky, limestone facade of Diderot’s grandparents’ house and look up into the windows of its second floor where he came into this world. On the same square, a hundred feet to the west, stands another landmark, the narrow four-story stone house that Didier Diderot purchased in early 1714 (several months after Denis’s birth) to accommodate what was destined to be a large household.

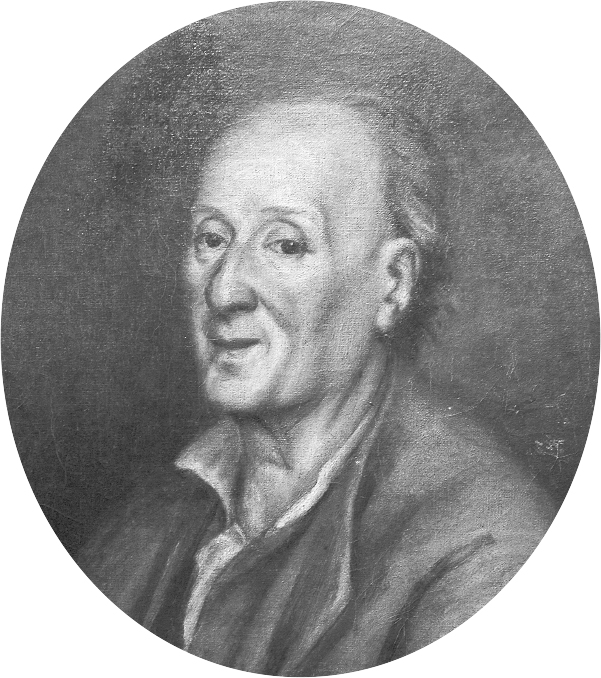

DIDIER DIDEROT

Angélique and Didier Diderot would ultimately have nine children while living on the place Chambeau, many of whom did not make it through the perilous first years of life. In addition to the baby boy who died before Denis was born, four girls succumbed to various ailments. One died when Denis was two, another when he was five, another when he was six. Yet another perished at an unknown date. The four surviving children, two girls and two boys, had dispositions that split down the middle. The older two siblings, the firstborn Denis and his sister Denise (1715–97) — Diderot once described her as a female Diogenes — had powerful personalities with ironic senses of humor. The younger children grew into far more somber and devout adults. Angélique (1720-c. 1749), about whom we know virtually nothing, insisted on joining the Ursulines’ convent at age nineteen. The youngest child in the family, Didier-Pierre (1722–87), also dedicated his life to God. Nine years younger than his brother, Didier-Pierre seems to have crafted his entire life as a response to his older sibling’s freethinking iconoclasm. He became disciplined where Denis was rebellious, pious where Denis was irreverent, abstemious where Denis was self-indulgent, and a doctrinaire priest where Denis was a skeptic. By the end of his career, Didier-Pierre had not only become a particularly unyielding member of the Langres clergy, but the archdeacon of the Saint-Mammès Cathedral.

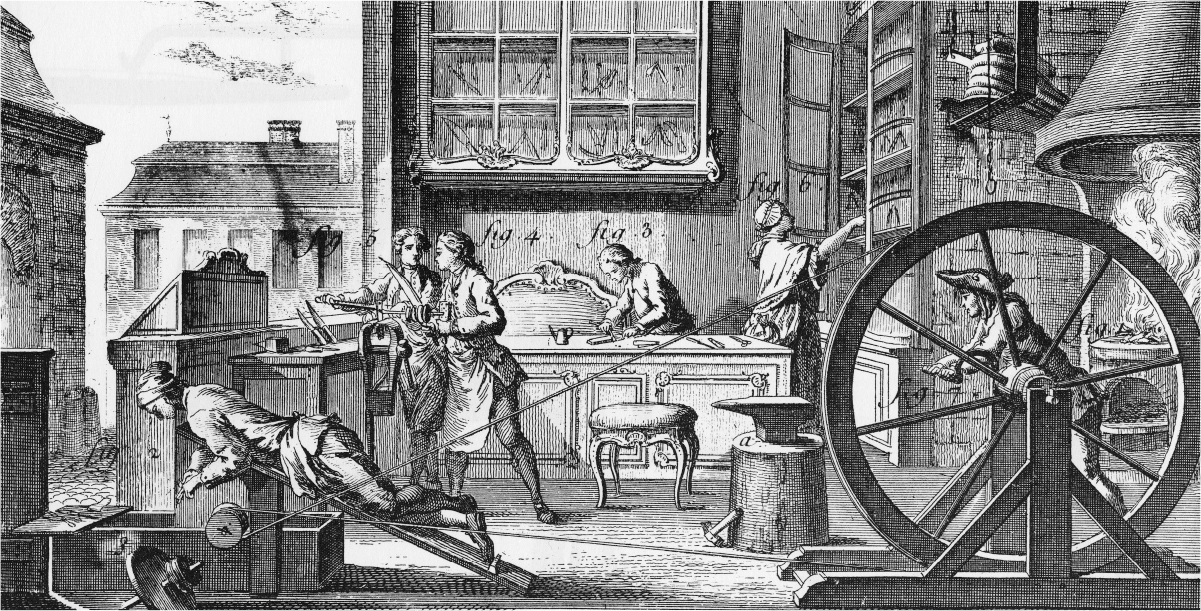

Denis and his three younger siblings grew up in a bourgeois milieu where girls would ideally enter into strategic and suitable marriages and boys would become cutlers, tanners, or perhaps priests. Diderot’s mother, née Angélique Vigneron, had come from a family that typically earned its living through the “odoriferous trade” of tanning and selling animal hides. Denis’s father, Didier Diderot, had also followed long-standing family tradition and embraced the profession of his father and grandfather as a fabricator of knives and surgical tools.5 Expanding the business inherited from his father, Didier became known throughout eastern France as the manufacturer of some of the finest surgical instruments in the region — including a type of lancet that he had invented.

KNIFE MADE BY DIDIER DIDEROT, MASTER CUTLER

Life in and around the place Chambeau revolved around the cutlery business. Six days a week, Diderot père came downstairs from his family’s living quarters to the ground floor workshop, where he toiled alongside several workers. The household was constantly filled with the sounds and smells of knife making: the smolder and respiration of the bellows, the incessant pings of the tack hammer, and the screech of the grinding wheel, which was operated by a worker lying on a plank, his nose quite literally to the grindstone.

WORKSHOP OF A CUTLER

Though Diderot ultimately had little affinity for the trade of cutler, he admired his father tremendously. Until his dying day, he praised the civic and moral values associated with Didier Diderot’s patriarchal, bourgeois world, even “staging” some of these values in his plays. The few written descriptions or anecdotes related to the elder Diderot all portray him as a hard worker, a profoundly religious man, and a devoted subject of the king. Didier Diderot’s granddaughter, Madame de Vandeul, also stresses his fairness and severity, describing him as the type of man who once took the three-year-old Denis to witness the public execution of a criminal outside the city walls. This horrific spectacle, she adds parenthetically, made the small boy violently ill.6

At some point during Denis’s childhood, his parents decided that he was not destined to become either a cutler or a tanner. Perhaps witnessing his startling intellect, they began to groom him for the priesthood, which had also been a career choice for a dozen or so blood relatives on both sides of the family. Diderot surely met many of these pious family members, among them the vicar in neighboring Chassigny, the two great-uncles and two second cousins serving as country priests outside the city walls, and another uncle who was a Dominican friar.7 The most important and prominent ecclesiastic in his life, however, was his mother’s older brother, Didier Vigneron, who occupied the coveted position of chanoine, or canon, in Langres’s cathedral.

For a number of years, Didier and Angélique Diderot not only hoped that their son would become a priest, but succeed his uncle as canon at the cathedral. Had Diderot replaced the aging Vigneron, he would have become an influential member of the cathedral’s Chapter, the group of clerics who controlled the Langres bishopric.8 In addition to garnering immense prestige for the family, the young canon would also have received a generous portion of the revenues — called a prebend — from a diocese whose reach extended to some six hundred parishes and seventeen hundred priests outside the city’s ramparts.9 In an era where a typical worker might earn two hundred livres a year, a canon’s basic annual income was a more than respectable one thousand to two thousand livres.

The young Denis took the initial, small step toward becoming a man of the cloth on his seventh birthday. This was seen as the dawn of the “age of responsibility” for young boys.10 From this point forward, the Sunday morning clangor of church bells called Denis to a day of worship and study at the neighboring Church of Saint-Martin. For the first few years that he attended church, the Latin liturgy washed over him ineffectually. After mass, however, Denis moved on to catechism, which was offered in French. This weekly obligation, which was conducted simultaneously in hundreds of churches throughout the Langres diocese, consisted of a particularly monotonous routine. Once the children were settled, the local curé or his representative read a series of scripted questions pertaining to matters of faith, religious practice, and God.11 The older children in attendance, who had memorized the answers over the years, responded in unison. The younger ones stammered out the answers as best they could.

In October 1723, at age ten, Diderot was admitted to Langres’s Jesuit collège, which was on the other side of the place Chambeau. Diderot was eligible for such an advanced education because he had the good fortune of being born into a family that could afford tutoring or ad hoc schooling in French and Latin, the languages required for admission. Once he had begun attending the collège, he (and his two hundred classmates) took classes that were largely based on the Ratio Studiorum, the formal “plan of education” created at the end of the sixteenth century by an international group of Jesuit scholars. In addition to deepening Diderot’s understanding of the foundational aspects of the Catholic faith, this program introduced the young boy to what we would now consider traditional humanities disciplines, such as ancient Greek, Latin, literature, poetry, philosophy, and rhetoric.12

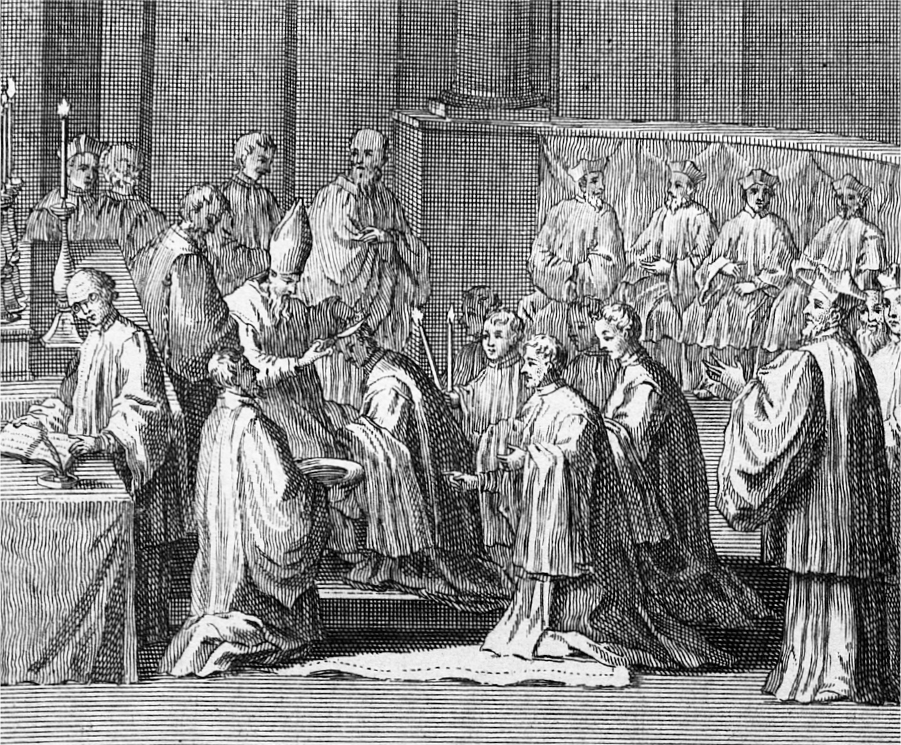

As the twelve-year-old Diderot was finishing his third year at the collège, he or his family decided that he should take the next step to joining the priesthood, by becoming an abbé, or abbot. This ceremony, which took place at the nearby Saint-Mammès Cathedral on August 22, 1726, followed a strict script. Diderot was called up from a pew and told to kneel before his diocese’s bishop, the doughy-faced Pierre de Pardaillan de Gondrin. The prelate then began the tonsuring ceremony, cutting several tufts of the boy’s blondish hair from the front, back, sides, and top of his head — forming a cross — and, after taking off his miter, prayed over the young Diderot. In the final part of the ceremony, the prelate helped the newly tonsured abbot don a white surplice, proclaiming that the Lord was reclothing him.13

TONSURING OF AN ABBOT

Diderot had entered into the minor orders, but the plan to have him succeed Vigneron as canon was doomed to fail. In the early spring of 1728 — less than two years after he had become abbé Diderot — the cathedral’s Chapter voted resoundingly against his uncle’s nepotistic succession plan. Furious, Vigneron decided to circumvent his own diocese and took the audacious step of writing directly to Pope Benedict XIII, asking him to push this promotion through. Unfortunately for the chanoine (and for his nephew’s budding career as a Langres ecclesiastic), Vigneron died while this letter was en route to the Vatican, thereby rendering his request null and void. Shortly thereafter, the Chapter voted to offer the position of canon to someone else. As a nineteenth-century historian of the Langrois diocese wistfully wrote, “If the death of Diderot’s cousin had only been delayed by a few days, the boy would have undoubtedly become canon in Langres…While Diderot might not have been an ideal canon, he would not have become a nonbeliever.”14

paris

After learning that he would not be replacing his uncle within the Saint-Mammès Chapter, the fourteen-year-old Diderot resigned himself to completing his final year at the collège. During his last months in school, he continued to distinguish himself as a brilliant and, at times, troublesome student. This began with the baiting of his teachers. By his own admission, Diderot apparently took a perverse pleasure in undertaking translations of Latin or Greek into which he slipped arcane, but grammatically accurate, syntax so that his teachers would correct him. He would then enjoy pointing out to his instructors where they were mistaken.

In addition to engaging in such erudite mischief, the young Diderot also had a tendency to get into scraps. On one occasion, after being sent home from school for fighting, he realized that he was missing out on the annual prize day, a day when his teachers were identifying their strongest pupils through a series of exams and competitions. Refusing to be shut out of the contest, he attempted to sneak back into the school by rushing in with the other students, but was singled out by the collège’s guard. While the sentinel was unable to prevent Diderot from slipping by, he nonetheless managed to stab the boy with his halberd. Bleeding from a wound that his family only found out about a week later, Diderot nonetheless prevailed over all of his classmates, winning prizes in essay writing, poetry, and Latin translation. In one of the few moments when he looked back at his days at the Jesuit collège in Langres, Diderot luxuriated in the memory of his triumphal return after the contest:

I remember this moment as if it were yesterday; I arrived home from school, my arms filled with prizes that I had won, and my shoulders covered with crowns that had been bestowed on me and that, because they were too big for my brow, had slipped over my head. My father saw me from afar, stopped work, walked into the doorway, and began to cry. It is a beautiful thing to see an honest, austere man cry.15

Two of Diderot’s most deep-rooted tendencies are present in this telling story: his eternal struggle against various forms of authority and the deep respect and admiration that he felt for his father.

Accolades and parental tears notwithstanding, by the time Diderot completed his studies at the collège in 1728, he was well aware that his career options in Langres had narrowed considerably. Rejected as canon — and having scorned the family occupation of cutler as unsuitably mind-numbing — the young Denis fell back on the possibility of a different ecclesiastical career, one that would involve further study of philosophy in Paris. It was at this time, it seems, that the young Diderot fell under the influence of a Jesuit priest who gave him the idea to run off to Paris to join the Society of Jesus. Diderot apparently told no one in his immediate family about these plans, though he did alert an indiscreet cousin who immediately informed Diderot’s father. On the night that Diderot was supposed to leave for the capital, his father caught him at the door. “Where are you going?” the elder Diderot apparently asked, to which Diderot replied, “To Paris where I’m supposed to join the Jesuits.” “Your desire to do so will be satisfied, but not tonight,” his father countered.16 Soon thereafter, Didier Diderot granted his son permission to study in Paris, but under conditions that he, as paterfamilias, would determine.

In late 1728 or early 1729, Didier Diderot booked two seats on the diligence coach that passed through Langres and Troyes on its way to the capital. The route to Paris crossed gently undulating plains and large expanses of farmland. Each night, after fifty or so miles of rutted, root-covered roads, the coach would stop at roadside taverns where the father and son would eat typical hostelry fare, most often mutton stew. After four or five days, they arrived in Paris, a city fifty times bigger than Langres.

As was inevitably the case for first-time provincial travelers coming into the capital, Denis and his father were presumably shocked by the tremendous concentration of soot-caked buildings, constricted, mud-filled streets, and foul neighborhoods teeming with starving, half-naked children. As they moved from the city’s outlying quarters to the heart of the capital, they must also have marveled at the scale of the royal and ecclesiastical architecture.

Their final destination in Paris was the young abbot’s new school, the collège d’Harcourt, which was located in the Latin Quarter, on the rue de la Harpe, about a five-minute walk from Notre Dame.17 Harcourt, a Jansenist-leaning institution within the University of Paris, was composed of a hodgepodge of contiguous buildings, some dating from the thirteenth century. Didier Diderot enrolled Denis in the school on a provisional basis, and rented a room in a nearby inn for two weeks. According to Madame de Vandeul, the young Denis nearly got expelled during this trial period because he helped a fellow pupil with Latin homework. The assignment, ironically enough, was an exercise on temptation, whose subject was “What the serpent said to Eve.” Despite the severe reprimand that Denis surely received for aiding his schoolmate, the would-be ecclesiastic ultimately announced to his father at the end of two weeks that he wished to remain at the collège. Once this decision was made, Diderot père and fils said their goodbyes. And soon thereafter, Didier Diderot made his way across the Seine to the rue de Braque to board the Langres coach. As he set off on this four-to-five-mile-an-hour journey back toward the southeast, the master cutler probably thought he would see his son a year or two later. Thirteen years would pass, however, before the two Diderots would meet again.

harcourt and the sorbonne

Life at the collège d’Harcourt was far from gratifying for Diderot. Much like the collège des Jésuites that he had attended in Langres, the structure of the school mirrored the social stratification of the ancien régime itself. Among the 150 or so boarders, the better-off students often had servants and fireplaces, while the students of more modest means, such as the son of a cutler, endured lesser quarters.

The daily routine was grueling. Students were called to prayer at 6:00 a.m. and spent the rest of the day in class and study sessions, during which they painstakingly copied their rhetoric and physics lessons into notebooks.18 The few interruptions in this routine included a very short recess after dîner (lunch) and, of course, various religious obligations, including an evening prayer at 8:45 p.m.19 The day of reckoning for each pupil came every Saturday. After mass, the school’s teachers went over the week’s work one final time before doling out rewards and punishments according to each student’s particular merit. While Diderot did not write about such rituals at Harcourt, later in life he often maligned the repetitive and reclusive world of the religious collèges into which, as he put it, some of his best years had vanished.20

THE COLLÈGE D’HARCOURT, ENGRAVING

After three years of study at Harcourt, on September 2, 1732, the nineteen-year-old Diderot earned the most common degree dispensed by the school, the maîtrise ès arts, which is roughly the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree today.21 Shortly thereafter, he entered the Sorbonne, the designated college of theology within the University of Paris.22 As was the case for all first-year students, Diderot began by studying philosophy here. During his second year, he went on to physics, theology, and, with far less enthusiasm, scholasticism. Like many of his fellow philosophes, Diderot harbored a great deal of scorn for the “frivolities” of the scholastic method, which involved the often tortured application of Aristotelian ideas to Church dogma. While details of these years are scant, it is quite easy to imagine how this increasingly skeptical thinker would have become exasperated among a sea of aspiring ecclesiastics, all engaged in scholasticism’s impenetrable debates on the distinctness of substantial forms, the different types of matter, the immateriality of the soul, and the final causes of all bodies. Voltaire best summed up these maddening abstractions when he quipped that the “sectarians of Aristotle use words that no one understands to explain things that are inconceivable.”23

VIEW OF THE SORBONNE,AQUATINT

Diderot never documented the precise reasons why he abandoned his plan to be a priest. What we do know, however, is that by 1735 the twenty-two-year-old had reached the point in his studies where he had the option of committing to an ecclesiastical career. Having completed five years of study — the quinquennium — in Paris, he was now eligible to apply for a respectable benefice or pension of perhaps four hundred or six hundred livres a year.24 In October 1735, he even seems to have flirted with this idea, going as far as taking the initial steps of registering such a request with the bishop of Langres, Gilbert Gaspard de Montmorin de Saint-Hérem. As would often be the case at such points in his life, however, Diderot never finished the application process, and simply let this opportunity pass.25

Diderot’s ambivalence toward the Church and further religious training intersected with his larger disinclination to commit to any real profession. From 1736 to around 1738, he worked halfheartedly for a solicitor named Clément le Ris, reportedly spending most of his time at the law office reading mathematics, Latin, and Greek, and teaching himself two new languages: Italian and English. Diderot’s obvious lack of interest in a legal career ultimately prompted the solicitor to write to Didier Diderot to let him know that his son was not working out. The elder Diderot reportedly asked le Ris to inform his reluctant employee that the time had come for him to choose among three professions: doctor, solicitor, or lawyer. Madame de Vandeul relates her father’s waggish reaction with a smile:

My father requested some time to think it over, and was granted this wish. After several months, the question was put to him again. He replied that the profession of doctor did not appeal because he did not want to kill anyone; that the profession of solicitor was too difficult to perform scrupulously; that he would gladly choose the profession of lawyer, except that he had an indomitable distaste for taking care of others’ affairs.26

Madame de Vandeul then recounts that her father was asked what he wanted to do with his life. He replied: “My gosh, nothing, nothing at all. I like to study; I am very happy, very content; I don’t ask for anything else.”27 Diderot’s relationship with the law and le Ris ended shortly thereafter.

To make ends meet, Diderot next found a well-paid position as a tutor to the children of a wealthy banker by the name of Élie Randon de Massanes. After three months of watching over and instructing the financier’s children — this task began at breakfast and ended with their bedtime — Diderot informed his employer that he could no longer stand being cooped up: “Monsieur,” he supposedly said, “[t]ake a look at me. A lemon is less yellow than my face. I am making men of your children, but with every day I am becoming a child with them. I am a thousand times too rich and too well-off in your house, but I have to leave it.”28

On the few occasions where Diderot referred to this unpredictable period in his life, he tended to downplay its difficulties and conjure up its joys, joys which included the occasional wooing of courtesans or actresses, long strolls in the Luxembourg Gardens, extended conversations with friends at cafés such as the Procope, and, if his purse allowed it, a place within the crowded, standing-only parterre at the Comédie-Française.29 How to pay for this self-indulgent existence soon became a problem, however. Although Diderot’s obstinacy and independence would serve him well later in life, in the second half of the 1730s these traits exasperated his father, who ultimately cut off his pension. His mother was apparently of a softer heart. On at least one occasion, she sent him some money via a servant who, incredibly enough, walked the 238 kilometers from Langres to Paris (and back) to deliver it to him.

Despite this occasional bit of help, Diderot had nonetheless sentenced himself to a hardscrabble life spent in a succession of Latin Quarter fleapits. This was an era of threadbare stockings, cold and empty fireplaces, and precious little food in the larder. His most consistent source of income in the late 1730s and early 1740s came from tutoring students in mathematics. There were other gambits as well. On one occasion, he reportedly drew on his theological training in order to produce a series of sermons for a missionary setting off for the Portuguese colonies.

Diderot’s most remarkable moneymaking scheme, however, involved swindling a Carmelite monk by the name of Brother Ange.30 Brother Ange had grown up in Langres and was either a friend or distant relative of the Diderot family. Like the other members of his monastic order, he resided in the Carmelite monastery situated just south of the Luxembourg Gardens. Diderot first got in contact with the friar under the pretense of touring the monastery’s library, which held over fifteen thousand volumes and manuscripts. As Madame de Vandeul joyfully recounts, her father let it be known during his initial visit that he had tired of the “stormy” existence he was leading outside the monastery’s walls and was now drawn to the peaceful and studious life of a monk.31 Brother Ange immediately realized that the erudite Diderot would be an excellent prospect for his order. After several more visits, Diderot announced that he had decided to become a postulant, but first needed to pay off his worldly debts. In particular, he informed Brother Ange that he needed to work for perhaps one more year to earn enough money to do right by a young woman whom he had dragged into sin. Fearing that this delay might slow things down, Brother Ange advanced Diderot 1,200 livres, a considerable sum. Shortly thereafter, Diderot returned to the monastery and informed the monk that he was now far closer to taking his vows but that he also needed to pay off his neighborhood’s public cook and his tailor. The good friar once again lent him another eight hundred or nine hundred livres. During his final visit to meet with Brother Ange, Diderot used the same line: he was very much ready to join the order, but he needed a last advance to purchase the necessary books, linens, and furniture for his new life. The monk assured him that none of this would be necessary and that all would be provided for him once he arrived. At this point, Diderot then decreed angrily that if the monk did not want to advance him any more money, then he no longer wanted to become a monk, and stormed off.32 Hoodwinked and humiliated, Brother Ange wrote to Didier Diderot, complaining that his son had defrauded him for over two thousand livres. The elder Diderot, who had already been obliged to repay similar debts, reimbursed the Carmelite, but not before deriding the monk for being so gullible.33

JEAN-JACQUES AND ANNE-ANTOINETTE

Diderot’s career as dilettante and occasional scoundrel came to a close, more or less, by the early 1740s. Now in his late twenties, he was not only reading deeply in mathematics, physics, and natural history, but had also taught himself both Italian and English, the latter language, improbably enough, by using a Latin–English dictionary. Mastering written English had an immediately positive effect on Diderot’s life. By early 1742 he was able to secure his first real gainful employment as a translator of Temple Stanyon’s The Grecian History.

It was during this same era that Diderot met some of the most important people in his life. In September 1742, while drinking coffee and watching games of chess at the Café de la Régence, Diderot was introduced to a fine-boned, thirty-year-old Genevan named Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau and Diderot realized straightaway that they had a remarkable store of things in common. In addition to their passions for chess, reading, music, theater, philosophy, and literature, they had also both rejected professions that would have provided settled, secure lives in favor of far more precarious careers. Even their relationship to their families had significant similarities: Rousseau, like Diderot, had grown up in a household in which the father was a skilled craftsman (a watchmaker in Rousseau’s case); what was more, both of these Parisian transplants were now alienated from their families.

The fundamental difference between the two men was one of temperament. Diderot was intensely optimistic, a powerful conversationalist, and far more effusive and confident than the introverted Rousseau. Some of this surely had to do with their respective familial histories. Diderot had chosen to leave his family, while Rousseau had felt orphaned or abandoned from his first moments on earth. Referring, in The Confessions, to the fact that his mother had died nine days after he was born, Rousseau famously proclaimed that “I cost my mother her life. So my birth was the first of my misfortunes.”34 Raised by his aunt and his father and lacking the formal education enjoyed by Diderot, the boy learned to read and write by poring over long adventure novels produced by the likes of Honoré d’Urfé. This comparatively peaceful time in his life came to an end shortly after his tenth birthday in 1722, when his father, Isaac Rousseau, was apprehended for trespassing on a noble’s property. Fearful of being condemned in court, he deserted his family and fled to Bern.

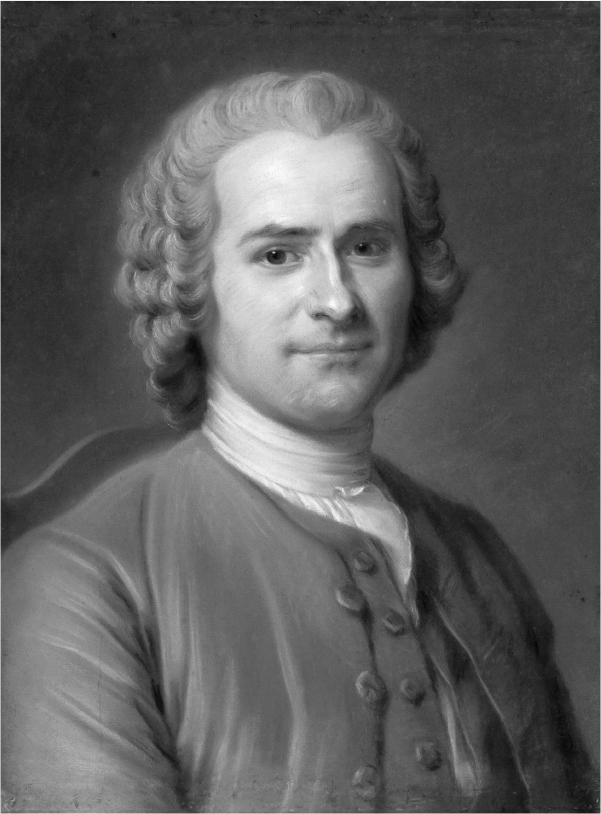

JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU BY LA TOUR

Handed off to yet another aunt along with his brother, Rousseau was soon dispatched to live with a Calvinist minister in the neighboring village of Bossey. Two years later, at age thirteen, Rousseau began preparing himself for his adult life by apprenticing with a notary and then a brutish engraver named Monsieur Ducommun, who would sometimes beat him mercilessly. At sixteen, Rousseau left Geneva and made his way to the city of Annecy, some forty miles to the west. It was here that he met a handsome, cow-eyed aristocrat named Françoise-Louise de Warens (née de la Tour du Pil), a woman who would function for the young philosophe as both surrogate mother and object of desire.

For the next ten years or so, Rousseau wandered from city to city, living in Turin — where he converted to Catholicism — as well as in Lyon, Montpellier, Neuchâtel, and Chambéry. Despite his many travels, he always returned to Annecy and Madame de Warens for extended stays. When he reached nineteen or twenty, his onetime mother figure took him as her lover. This curious arrangement lasted until the summer of 1742, when Madame de Warens replaced Rousseau with another young and lost Calvinist. It was at this point that the thirty-year-old Rousseau decided to move to Paris, where he quickly inserted himself into the group of writers and philosophes who would ultimately be responsible for the Encyclopédie.

During the same months that Rousseau was settling into life in the capital, Diderot was busy courting the woman whom he considered to be the love of his life: the alluring, statuesque, and very pious Anne-Antoinette Champion.35 At thirty-one years old, this hardworking laundress, whom Diderot called Toinette or Nanette, should have been leading the life of a provincial noble in her hometown of Le Mans, married to someone befitting her rank and beauty. A series of financial disasters, however, had struck her family. The hard luck had begun with her grandfather who, like many military-oriented aristocrats, ruined himself by playing at war.36 His daughter (Anne-Antoinette’s mother) was nonetheless able to leverage her noble birth and marry decently, to Ambroise Champion, a wealthy bourgeois whose fortunes were heavily tied to the fur trade. This marriage also ended in financial disaster. Much like his aristocratic father-in-law, Champion went bankrupt, his investments disappearing in the snowy forests of Canada. To make matters worse, he fell ill soon thereafter and died in 1713, leaving his young wife and three-year-old daughter alone and destitute. Faced with few prospects, the widowed Madame Champion subsequently traveled to Paris with her daughter, where she set up a small business as a laundress, a profession far below her station. With the little money that she had either kept from Le Mans or earned in the capital, she soon dispatched Anne-Antoinette to the Miramiones convent. The young girl emerged from her seclusion at age thirteen or so, barely able to read.37

Diderot had started cozying up to Mademoiselle Champion in 1741, when he happened to move into the same building where she and her mother were living, on the rue Boutebrie. After initially running afoul of Madame Champion, he realized that to have any success with the beautiful thirty-one-year-old laundress, he would need to overcome her mother’s qualms with a bit of deception. Announcing that he was on the verge of entering the priesthood — in this particular instance, at the Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet seminary on rue Saint-Victor — Diderot reintroduced himself to the Champion household as an unthreatening future ecclesiastic who, as it happened, often needed the services of the two laundresses. As Madame de Vandeul recounts this story, this ploy allowed her professionless father to overcome Madame Champion’s well-placed skepticism and spend more time with Toinette. Eventually, Diderot was not only able to declare his love, but let Toinette know that he had concocted the entire scheme because he had wanted to marry her in the first place. Sometime later, when Diderot finally announced his intentions to Madame Champion, the older widow recoiled at the idea that her daughter would “marry a man with such a flashy mind, a man who did nothing, a man whose sole quality was…the silver tongue with which he had so completely seduced her daughter.” But this hesitancy, according to Diderot’s daughter, soon gave way.38 Once Diderot had received Madame Champion’s blessing to marry Toinette, he decided that he should ask his parents’ permission as well. Stitching together the money for the Langres coach, the young man returned home in December 1742 for the first time since leaving for Paris more than a decade before.39

Diderot’s short stay in Langres began as well as could be expected; it would end, however, in incarceration. The first thing that he did upon arriving was to explain what he had been doing in the capital. Over the years, news trickling back from Paris had given him the reputation of a ne’er-do-well, a loafer, and a possible freethinker who was seemingly incapable of finding a proper career for himself. By 1742, however, he was able to present himself to his parents and friends as one of the new “men of letters” taking Paris by storm. This image was spectacularly confirmed in Langres thanks to Antoine-Claude Briasson, the publisher who had commissioned Diderot’s translation of Temple Stanyon’s The Grecian History.40 Having reached the point in the project where the book was going to print, Diderot had made arrangements before he left to have the book’s proofs sent to him via the coach. These periodic dispatches from Paris to Langres apparently impressed Diderot’s family no end. How amazing, indeed, that an important Parisian publisher was going to the trouble of sending printed pages by carriage to the young man in Langres! Diderot’s family once again had reason to brag about their son, the ecclesiastic-turned-important-translator.

Diderot’s self-presentation as the prodigal son — once lost, now found and redeemed — came to an abrupt end when he finally revealed the primary motive behind his trip: asking his parents’ permission to marry a laundress with no father, no dowry, and who, despite her birth, was obviously a less-than-ideal match for their firstborn son. To add insult to injury, Diderot also requested a stipend of twenty-five pistoles (2,500 livres) per year to support his new household.41 Didier Diderot reacted to this proposition with disdain. The sacrament of matrimony, everyone knew, was not merely about love and tenderness: marriage was a yoke that parents placed over their children’s necks. Until the age of thirty, in fact, Diderot did not have the right to legally marry without their consent.

After a ferocious dispute during which Diderot fils threatened his father with legal action, the elder Diderot had his son locked up behind the walls of what many historians now assume was the neighboring Carmelite monastery. Once this was accomplished, Didier dashed off an unfeeling letter to Toinette’s mother, hoping to drive a wedge between the irresponsible lovers once and for all: “If your daughter is [really] of noble birth and loves [my son] as much as he claims, she will convince him to forsake her. This is the only way that my son will be released. With the help of a few friends who were as outraged by his audacity as I was, I have had him locked away in a safe place, and it is within our ability to keep him there until he changes his mind [about your daughter].”42

While this letter traveled to Paris, the Carmelite monks who held Diderot were only too happy to teach the reckless lover a lesson. According to Diderot’s own account of this episode, the friars not only delighted in taunting and manhandling him, but also cut off half of his hair, ostensibly so that he would be easy to identify if he escaped. While such punishment was perhaps sanctioned by Diderot’s father, it is also possible that the order’s members delighted in evening the score with the young man who had made a fool of one of their own, the aforementioned Brother Ange.

Diderot’s shearing at the hands of the Carmelites turned out to be his second and last tonsure in Langres. After several days of captivity, he managed to climb through an open window sometime after midnight. He then presumably made his way to the porte du marché, the closest gate within the walled city. Passing through the stone gateway, the fugitive then walked 120 kilometers to Troyes, fearing, quite reasonably, that his father would dispatch men to bring him back. Once he had arrived at this midway point between Langres and Paris, Diderot found an inn and penned a dramatic note to Toinette, before boarding the Paris coach: “I have walked thirty leagues in atrocious weather…My father is in such a fury that I am sure that he will now disinherit me, as he threatened. If I lose you again, is there anything that could convince me to remain in this world?”43 Toinette must have been devastated. Diderot had gone to Langres with promises of obtaining both an allowance and parental consent to marry; he was now returning to Paris a reprobate and an escapee.

The next months were emotionally distressing. Rejected by his family and anxious that he might be arrested and dragged back to Langres in irons, Diderot was forced to abandon his former apartment and take up squalid quarters on rue des Deux-Ponts on the Île de la Cité. Worse yet, he discovered upon his return that Toinette had been deeply affected by the letter that his father had sent to her mother; she informed him in no uncertain terms that she had no intention of marrying into a family “where she was not regarded favorably” and broke off the engagement.44

According to Madame de Vandeul, Toinette apparently did not waver in her resolve until early 1743, when she was informed that her erstwhile lover had fallen gravely ill in his small room on the Île de la Cité. She (and her mother) ultimately flew to her ex-fiancé’s sickbed, where they discovered the young man in a pitiful and emaciated state.45 The two women then took it upon themselves to nurse the malnourished and ailing Diderot back to health. Sometime during or shortly after this stint of caregiving, Toinette broke her previous vow and once again agreed to marry Diderot. The couple were wed on November 6, 1743, at the nearby Church of Saint-Pierre-aux-Bœufs, one of the few Parisian parishes where young couples could be married without parental consent. Though Diderot had turned thirty in October and was thus able to wed Toinette legally, he nonetheless arranged an inconspicuous ceremony that took place at the stroke of midnight.

Other than several sentimental love letters that he sent to Toinette, Diderot preserved very little correspondence from this era. He wrote about these early years, curiously enough, while commenting on a painting by Nicolas-Guy Brenet exhibited at the Salon of 1767. Twenty-five years after he had first met his future wife, he summed up this tumultuous time in his life in his characteristically flippant style:

I arrive in Paris. I was going to adopt academic garb [robe with a fur collar worn by the professors of theology] and install myself among the doctors of the Sorbonne. I encounter a woman beautiful as an angel; I want to sleep with her, and I do; I have four children with her and find myself obliged to abandon the mathematics I loved, the Homer and Virgil that I always carried in my pocket, and the theater I enjoyed.46

What Diderot leaves unsaid here speaks volumes. Writing about his own life as if he were the victim of unavoidable circumstances, Diderot passes over the painful fact that his father had actually been right about Toinette; her upbringing and social standing ultimately made her a poor match. Missing as well from this account is the immense guilt that Diderot felt (and sometimes admitted) about this time in his life, an era during which he let down his father, did not visit his mother before she died, and created a terrible rift in the Diderot clan. But there is also a good deal of psychological truth present in this cursory assessment of his early years. Despite the fact that Diderot takes little responsibility for his own actions, he nonetheless acknowledges the legitimacy of his own longing, as well as his lifelong tendency to embrace existence fully, completely, and audaciously, with little regard for the potential consequences. It was this precise aspect of his temperament that would soon lead him to write a series of books challenging the religious foundations of the ancien régime itself.