III

A PHILOSOPHE IN PRISON

Diderot’s first brush with the Paris authorities came not long after Philosophical Thoughts appeared in 1746. At the time, he and his small family were still living on the rue Mouffetard in a first-floor apartment (or room) belonging to a friend named François-Jacques Guillotte.1 A military officer who later contributed an article on bridges to the Encyclopédie, Guillotte presumably tolerated or even enjoyed Diderot’s animated conversation and freethinking. Guillotte’s wife, on the other hand, was appalled by the blasphemous ideas that she heard under her roof.2 Only a year after standing as godmother to the Diderots’ second child — the ill-fated François-Jacques — Madame Guillotte marched down to the neighboring Church of Saint-Médard to denounce her lodger. On the receiving end of this complaint was the recently ordained curé Pierre Hardy de Levaré.3 Convinced that it was his duty to protect his flock from subversive thought, the priest passed on Guillotte’s allegation to a royal gendarme named Perrault, who then contacted the all-seeing lieutenant-général de police, Nicolas-René Berryer, comte de La Ferrière.

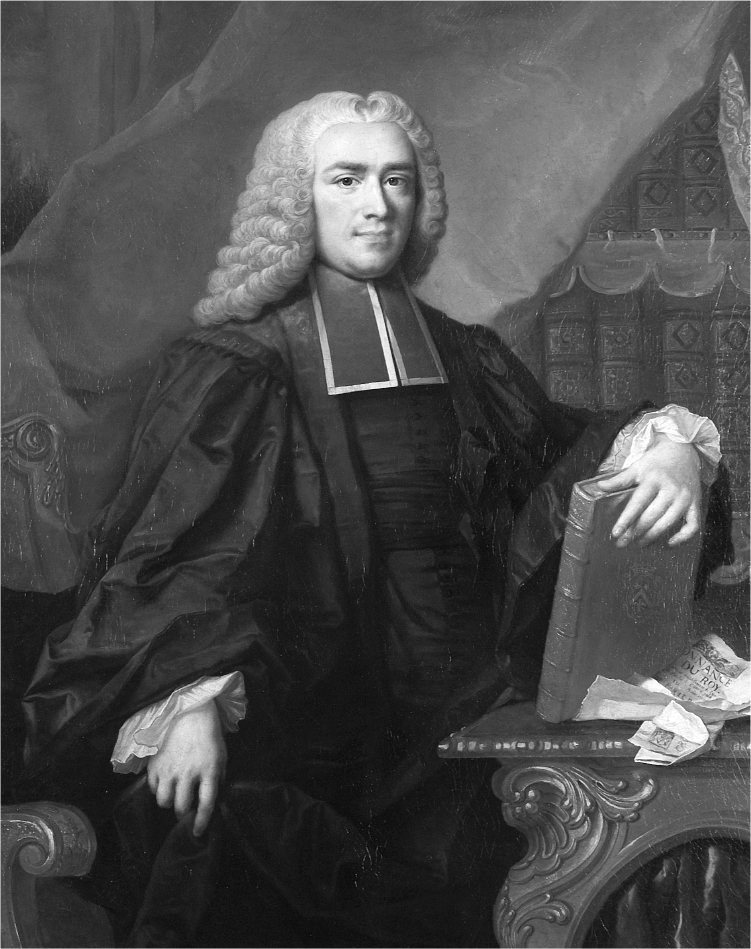

In his capacity as a royally appointed magistrate, Berryer had power and responsibilities far in excess of what we now associate with law enforcement. In addition to policing trade standards, criminal activity, thousands of prostitutes, the servant class, the poor and the indigent, as well as Paris’s chronic sewage and mud situation, Berryer also supervised the French publishing industry. To keep tabs on this powerful guild — along with the pack of writers who made their home in the capital — Berryer ran a massive intelligence-gathering operation with hundreds of spies.4 These informants, referred to as his mouchards (flies or snitches), reported to him on a range of misdeeds, including seditious thinking, violations of public morality, and written challenges to religious orthodoxy.5

NICOLAS-RENÉ BERRYER, PAINTING

Madame Guillotte’s tip was the first such accusation against Diderot to arrive on Berryer’s desk. As he did for hundreds of other novelists, playwrights, poets, and journalists, Berryer would eventually create a file on “sieur Didrot [sic].” The first documents came to include Perrault’s assessment that “Diderot is a dangerous man who speaks of the sacred mysteries of our religion with scorn.”6 He also inserted a follow-up note by Father de Levaré that castigated Diderot for marrying without his father’s permission and being a “libertine,” a “blasphemer,” and a “deist, at the very least.”7 Such information, in Berryer’s opinion, clearly merited an interview and a warning. As early as 1747, he dispatched the police inspector in charge of the book trade, Joseph d’Hémery, to advise Diderot to keep his sacrilegious views to himself.8 D’Hémery not only passed on this message, but also confiscated a manuscript version of La promenade du sceptique (The Skeptic’s Walk), which the writer had presumably hoped to sell to his publisher, Laurent Durand, at some point.

The Skeptic’s Walk disappeared into the police archives and Diderot never saw it again during his lifetime. (It was finally rediscovered and published in 1830.) Though Diderot lamented this loss, critics generally agree that this early text — which was perhaps even written before Philosophical Thoughts — is not nearly as interesting as the other works he wrote in the 1740s. Lacking the dialogical verve that he infused into his later writings on God, The Skeptic’s Walk is a somewhat plodding allegory that describes three paths one might take in life: the path of thorns (Christianity), the path of chestnut trees (philosophy), and the path of flowers (carnal pleasure). The most thought-provoking portions of the text come among the chestnut trees, where Diderot conjures up an Athens-like academy of philosophy where skeptics, Spinozists, atheists, and deists have at it.9 Diderot inserted his more anticlerical positions during the discussion of the Christian-inspired path of thorns, where an illogical “prince” rules over his blindfolded soldiers as they tramp ignorantly through life.

Despite d’Hémery’s discovery that Diderot had produced yet another unorthodox text, the author was let off with a warning. The lieutenant-général de police most likely wanted to avoid transforming the writer into a persecuted and celebrated martyr. For a time, Louis XV himself played a role in encouraging this policy of relative clemency. Often positioning himself against the far more volatile Parlement and Church, the king and his royally appointed officers sought to find a balance between creating scandals, supporting the hugely profitable book trade, and maintaining the kingdom’s orthodoxy.

Diderot surely benefited as well from the fact that he was increasingly seen as a thoughtful man of letters. While Berryer and those responsible for overseeing the book trade were perfectly aware that he had published the impious Philosophical Thoughts, they also recognized that he was also one of the translators of Robert James’s A Medicinal Dictionary (1746–48) and was currently working on Memoirs on Different Mathematical Subjects (1748), a short work which demonstrated how math could elucidate problems related to the physical world, including harmonic theory. Most importantly, however, Diderot had been hired by the eminent printer André-François Le Breton to contribute to the forthcoming Encyclopédie project, which was being referred to as a matter of national pride.

Yet neither his “worthwhile” ventures nor the warning he received from d’Hémery dissuaded Diderot from further testing the limits of the ancien régime’s patience. Not long after receiving his visit from the police inspector, the writer anonymously published his first novel, an erotic tale entitled Les bijoux indiscrets (The Indiscreet Jewels, 1748). This story of an African sultan whose magic ring could compel women’s genitals to recount their erotic adventures — a book to which we will return — was followed by an even more dangerous work.10 The following summer, while he was busy laying the groundwork for the first volume of the Encyclopédie, Diderot published his Letter on the Blind. This polished and complex work of free-flowing philosophy aimed to refute the existence of God in a way that The Skeptic’s Walk and Philosophical Thoughts had not.

LEADING THE BLIND

In early June 1749, Diderot received some of the first copies of the Letter on the Blind to come off the press. In addition to keeping an edition or two for himself, he likely reserved copies for Jean-Jacques Rousseau and for his then-mistress, Madeleine de Puisieux. More strategically, he dispatched a copy to the most famous philosophe of his generation, the fifty-four-year-old Voltaire, whom he had never met.11 Voltaire was not only flattered, but obviously very keen to see what the young and impudent philosophe had concocted in this meandering two-hundred-page “letter.” Three years earlier, the famous philosophe had carefully read and annotated Diderot’s Philosophical Thoughts, sometimes exalting in the young writer’s enthusiasm, other times taking him to task for his atheistic leanings.

Diderot had doubtless thought that Voltaire — the most celebrated French champion of Locke — would find his discussion of perception and sightlessness to be a stimulating read. The book, after all, was filled with a fascinating examination of how the congenitally blind reacted to regaining their sight after a cataract operation, how they envisioned and adapted to a dark world, and, more generally, how sensation itself is relative. Voltaire read the Letter as soon as he received it — he was in Paris at the time — and wrote back to Diderot a day or so later, praising the author for his “ingenious and profound book.”12 After dispensing with these pleasantries, however, Voltaire made plain that he had serious qualms over the climax of the work, a scene where one of the book’s characters forcefully denies the existence of the deity “because he was born blind.”13

NICHOLAS SAUNDERSON, ENGRAVING

The “character” to which Voltaire refers was a real person named Nicholas Saunderson (1682–1739), the most famous blind man to have lived during the eighteenth century. This prodigy had been a distinguished professor at Cambridge, the author of the influential ten-volume The Elements of Algebra, and a student of Newton’s. Much of Diderot’s account praises the unseeing man’s astonishing abilities: his exquisite sense of touch, his uncommon capacity to relate abstract ideas, and the system of “palpable” arithmetic he had created for himself. Toward the end of this discussion, however, the narrator of Diderot’s text interrupts himself and announces that he will now share the true story of the last moments of the blind man’s life. This portion of the Letter, supposedly based on unpublished manuscript “fragments,” was entirely fabricated by Diderot himself.14

The staging of Saunderson’s deathbed scene initially hints at a triumphal religious conversion, one where a man of science finally humbles himself before the truth of Christianity. But what follows is far from a return to the faith; instead, Diderot’s version of Saunderson launches into an impassioned debate on the existence of God with Gervais Holmes, a Protestant minister who is there to give the blind man his last rites.15 In contrast to Diderot’s Philosophical Thoughts — where deist, atheist, and skeptical viewpoints spar without clear resolution — Saunderson’s godlessness here overpowers Holmes’s deistlike presentation of Christianity. Among other things, the blind man ridicules the minister for explaining the wonders of nature with pathetic fairy tales: “If we think a phenomenon is beyond man, we immediately say it’s God’s work; our vanity will accept nothing less, but couldn’t we be a bit less vain and a bit more philosophical in what we say? If nature presents us with a problem that is difficult to unravel, let’s leave it as it is and not try to undo it with the help of a being who then offers us a new problem, more insoluble than the first.”16

Saunderson then reframes this same idea with a much more mordant parable:

Ask an Indian [from India] how the world stays up in the air, and he’ll tell you that an elephant is carrying it on its back; and the elephant, what’s he standing on? “A tortoise,” [says the Indian]. And that tortoise, what’s keeping him up?…To you, Mr. Holmes, that Indian is pitiful, yet one could say the same thing of you as you say of him. So, my friend, you should perhaps start by confessing your ignorance, and let’s do without the elephant and the tortoise.17

These two paragraphs are as much about humanity’s conceit and bigheadedness as they are about atheism. Through his blind oracle, Diderot asks us why we continue to look beyond nature in order to explain nature. He then supplies the answer: we have created this illusory myth so that we may flatter our own supposed self-importance.

Treating believers as bumptious fools — imploring them to do away with their “tortoise” — was not Saunderson’s last word. Shortly before he dies, he enters into a delirium during which he invites us to consider how the universe might have come into being. This poetic vision of the primordial soup is among the most daring passages ever published during Diderot’s lifetime:

[W]hen the universe was hatched from fermenting matter, my fellow men [blind men] were very common. Yet could not [this] belief about animals also hold for worlds? How many lopsided, failed worlds are there that have been dissolved and are perhaps being remade and redissolved every minute in faraway spaces, beyond the reach of my hands and your eyes, where movement is still going on and will keep going until the bits of matter arrange themselves in a combination that is sustainable? Oh philosophers! Come with me to the edge of this universe, beyond the point where I can feel and you can see organized beings; wander across that new ocean with its irregular and turbulent movements and see if you can find in them any trace of that intelligent being whose wisdom you admire here.18

For the eighteenth-century reader, Saunderson’s dreamlike vision of failed worlds and monstrous human prototypes would have recalled Lucretius’s De rerum natura. What is innovative about this part of the Letter, however, is how Diderot makes use of this vision of chance and godlessness. Rather than fold this into a pedantic account of the earth’s origins, Diderot lets Saunderson’s visionary ideas emerge from his agitated, delusional state. This atheistic fever is supposed to be contagious, infecting us with the idea that we are little more than the fleeting result of happenstance.19

VINCENNES

Sometime during July 1749, the second-most powerful man in France, the Comte d’Argenson — his administrative titles included royal minister of the press, minister of censorship, minister of war, and supervisor of the Department of Paris — received a complaint about an irreverent book published by an upstart philosophe named Denis Diderot. This time the grievance did not originate from a mouchard, censorious priest, or attentive censor; it had come from one of the minister’s friends, Madame Dupré de Saint-Maur, who had philosophic ambitions of her own.

Dupré de Saint-Maur had been disparaged. In the first paragraphs of the Letter on the Blind, Diderot (or, more precisely, his narrator) had complained that he was not invited to observe one of the first cataract operations in France, which had been presided over by René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur. The narrator went on to ridicule those who attended the procedure as dimwitted “eyes without consequence.” Dupré, who had been present at the event, felt personally attacked and presumably asked d’Argenson to teach the disrespectful philosophe a lesson about criticizing his betters.20

Had the Letter appeared at any other time, the minister of censorship might have ignored his lady friend’s grousing. But Diderot’s past brazenness, heretical ideas, and police file came to d’Argenson’s attention during a tumultuous moment in French history. Economic troubles, widespread starvation among the urban poor, and an almost universal disappointment with the terms of the peace treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle — which required France to return most of present-day Belgium to Austria — had led to widespread unrest and disenchantment.21 Paris had been on edge for months.

Some of the turmoil of 1749 had come from decommissioned soldiers who were wreaking havoc in the capital, including abducting and killing a number of women during a “celebration of the peace” ceremony near the Hôtel de Ville. A flurry of antigovernment poems and songs were also crisscrossing the city.22 What was perhaps most galling to Louis XV was the pervasive rumor that he had supposedly ordered the police to kidnap the capital’s children and take them to Versailles, where he was supposedly having them slaughtered so that he might bathe in their blood, thereby purifying himself of his sins. Not surprisingly, the king called on d’Argenson to reassert control over both the population and this circulation of unseemly ideas. This he did. By the spring of 1749, all fifty cells in the Bastille were full with tax protesters, “philosophes, Jansenists, and people who simply spoke ill of the regime.”23

It was in this anxious climate that d’Argenson decided to make an example of Diderot. On July 22, he ordered Berryer, the lieutenant-général de police, to arrest the writer and take him to the Château de Vincennes, a former royal palace that had been converted into a prison. Two days later, Agnan Philippe Miché de Rochebrune, a lawyer at Parlement and commissioner of police, and Joseph d’Hémery, the inspector of the book trade, arrived at Diderot’s apartment on the rue de la Vieille Estrapade at 7:30 a.m. to take the writer into custody. After gaining entrance into his second-story flat, they interrogated the writer and searched for any papers or works that attacked morality or religion.24

Based on Berryer’s file on the writer, which included the testimony of a printer who had divulged the exact list of Diderot’s publications, Commissioner Rochebrune hoped to unearth a treasure trove of impious treatises or pornographic short stories. (In later years, it was discovered that Rochebrune had actually gathered a substantial collection of forbidden works for his own edification.)25 Yet the commissioner found nothing akin to the talking vaginas of Diderot’s The Indiscreet Jewels or any discernibly materialist treatises. What he reported in his inventory was twenty-one wooden boxes of manuscripts related to the as yet unpublished Encyclopédie and a manuscript version of the already published Letter on the Blind.

Rochebrune nevertheless informed Diderot that he was the object of a royal lettre de cachet, a writ of incarceration signed by Louis XV himself at his royal residence in Compiègne. This legal document, one of the most hated expressions of arbitrary power associated with the ancien régime, could send prisoners to jail without a trial, in certain cases for life. According to Madame de Vandeul’s account of this episode, her mother, Toinette, was in a back bedroom getting François-Jacques dressed when Berryer’s men arrived. Once Diderot realized that he was being taken to prison, he asked and received permission to let his wife know that he was leaving. For fear of worrying her, however, he simply said that he needed to take care of some business related to the Encyclopédie and that he would see her later that evening. A few minutes later, perhaps feeling like something was not quite right, Toinette stuck her head out of the window and saw one of the guards shoving her husband toward the waiting coach. Finally realizing what had transpired, she collapsed.

Diderot’s eight-kilometer trip from the rue de la Vieille Estrapade to the Château de Vincennes — just east of Paris — took about an hour. D’Argenson had specified that Diderot be taken to Vincennes because the Bastille’s cells continued to be full of political prisoners, among them a significant number of purveyors and aficionados of antigovernment poetry.26

THE CHÂTEAU DE VINCENNES

Upon his arrival at Vincennes, Diderot was once again interrogated and then shepherded to a cheerless cell within the château’s massive dungeon tower. Today it is possible to visit this imposing 165-foot-tall fortification, including the rooms that served as prison cells. Contemporary craftsmen and stonemasons, however, have restored much of the dungeon tower to its former glory as a royal manor used by French kings from the fourteenth to the seventeenth century. This was hardly what the tower looked and felt like in 1749. As Diderot described it, the part of the dungeon he inhabited had become a foul-smelling and (as he would claim) disease-producing hideaway where the monarchy locked up its undesirables.27

SOLITARY

Incarcerated life under the ancien régime could vary widely. While all prisons had their share of lice, mice, rats, and rampant contagions, prisoners at Vincennes received different treatment based on their presumed wrongdoings, notoriety, or social class. Aristocratic or wealthy internees, with the right bribes or relations, could readily arrange for a comfortable internment. When the Marquis de Sade was arrested and taken to the prison in the late 1770s, he quickly made the best of his situation by paying to have his cell furnished with Turkish carpets, his own furniture, and a library with hundreds of volumes. The contrast with political prisoners such as Jean-Henri Latude, could not have been more stark. Unlike Sade, Latude had incurred the full wrath of the state by sending a box of poison to Louis XV’s cherished mistress, the Marquise de Pompadour, in 1749. The intention of this struggling writer had not been to do her harm, however. On the contrary, the misguided man had actually hoped to become a national hero by informing Pompadour of the conspiracy shortly before she ingested any of the toxin. This gambit backfired spectacularly. Not long after the deadly package arrived, Latude was quickly identified as the culprit and ended up spending the next thirty-five years locked up in both Vincennes and the Bastille, often consigned to dungeon cells with little more to eat than stale bread and bouillon.28

Police documents indicate that Diderot’s treatment fell somewhere between Sade’s and Latude’s. While the philosophe was confined to an insalubrious room in the dungeon tower, Berryer instructed the château’s warden to treat him decently, exactly like “Boyer and Ronchères,” two Jansenist priests who were spending the rest of their lives in prison for publishing anti-Jesuit tracts.29 This meant that Diderot was to receive his food at the king’s expense, generally a bowl of pot roast or, occasionally, liver or tripe, along with a bottle of wine and a large serving of bread.30 On Fridays, the prison served cheap fish — herring or stingray — along with some boiled vegetables.31

Diderot had settled into this routine for a week before Berryer finally reached out to him about his case. On Thursday, July 31, the chief of police himself made the trip from Paris to Vincennes to interrogate the philosophe about his activities. The transcript from their encounter not only contains the specifics of the debriefing, but Diderot’s continued attempts to deceive his interrogator:

Interrogation…of Mr. Diderot, prisoner by order of the King in the Dungeon of Vincennes…on the 31st of July, 1749, in the afternoon, in the counsel room of the aforementioned keep, after the prisoner swore to tell and respond truthfully.

Interrogated regarding his names, surnames, age, class, country, address, profession, and religion:

[Prisoner] replied that his name was Denis Diderot, native of Langres, 36 years old, from Paris, when he was arrested on rue de la Vieille Estrapade, in the Parish of Saint-Étienne du Mont, and of the catholic, apostolic and Roman faith.

Asked if he had authored a work entitled: Letter on the Blind for the Benefit of Those Who See:

He replied no.

Interrogated by whom he printed the same work:

He replied that it was not he who published the book.

Asked if he had sold or given the manuscript to someone:

He replied no.

Asked if he knew the name of the author of the work:

He replied he had no idea…

Asked if he composed a work, that appeared two years before, and that was titled The Indiscreet Jewels:

He said no, etc.32

In the remainder of the document, Berryer asks about each of the works that Diderot had been accused of writing. Each time, Diderot denied having anything to do with the manuscripts, the publishers, or the distribution of said books. At the end of the interview, the philosophe read through the questions and answers, attested to their validity, and signed his name.

Diderot’s fraudulent defense did not sit well with Berryer. Irritated by the philosophe’s stonewalling, the police chief returned to Paris and immediately ordered the interrogation of Diderot’s publisher, the thirty-seven-year-old Laurent Durand. Brought before Berryer the very next day, Durand was far more cooperative than Diderot, quickly revealing the history of clandestine arrangements into which he had entered in order to publish the author’s proscribed books. Proof in hand, Berryer now had very little incentive to free the unrepentant philosophe. His next move, which turned out to be quite effective, was to simply cease communication with his prisoner.

Eight days after Berryer interrogated Diderot — and approximately three weeks after Diderot had been taken to Vincennes — the philosophe understood that the deafening silence coming from Paris meant his time in prison would not be measured in weeks, but in months or years. This became painfully clear one day when a guard came by his cell to provide him with his weekly allotment of candles, which amounted to two per day. According to Madame de Vandeul, Diderot informed the jailer that he did not need any at this point, for he had plenty in reserve. The guard replied curtly that he might not need them now, but that he would be glad to have them in the winter, when the sun came up shortly before nine and set well before five p.m.33

Diderot’s stubbornness began to waiver by the middle of his fourth week in the isolated cell. Requesting paper, he sent carefully worded letters to both Count d’Argenson and Berryer. In his letter to d’Argenson, he employed a dual strategy. At times, he apologized somewhat vaguely for his indiscretions; more effectively, perhaps, he laced his missive with flattery and a thinly disguised inducement. After commending the count for being a great supporter of the era’s literature, Diderot let slip that he (as editor of the Encyclopédie) had been on the cusp of announcing that the entire project was going to be dedicated to d’Argenson himself. The message was crystal clear: release me and the dedication page of the forthcoming Encyclopédie is yours. Two years later, this tribute appeared in the first volume of the great dictionary.34

At the same time that he was enticing d’Argenson, Diderot threw himself on the mercy of Berryer in a longer and more doleful letter. After conjuring up the possibility of dying an agonizing death in his cell, he spilled a great deal of ink playing up his career as a diligent intellectual engaged in disseminating math and “letters.” No mention was made, however, of why he had been imprisoned in the first place.

This absence did not escape Berryer’s notice, and once again the police chief did not respond to Diderot’s letter. Increasingly desperate, Diderot sent another note to Berryer in which he not only admitted to being the author of Philosophical Thoughts, The Indiscreet Jewels, and Letter on the Blind, but also apologized for sharing these “self-indulgences of the mind” with the French public. A week after receiving this confession, Berryer traveled personally to the prison to speak to Diderot, and told him that he would soon be liberated from solitary confinement and given a proper room and bed, provided that he promise in writing not to do anything in the future that would be in any way contrary to religion and good morals.35

While carrying on these negotiations with both Berryer and d’Argenson, Diderot also managed to write two letters to his father in Langres.36 Though the two men had been estranged for more than six years, the thirty-four-year-old Denis had obviously dreaded the moment that his father (and the rest of Langres) would hear of his imprisonment. To temper the effect that this news might have in his home city, he hinted in at least one of his letters that he had been the victim of slander and that the police were accusing him of publishing books that he had not authored. While this was technically true — Berryer had accused him of being the author of François-Vincent Toussaint’s outlawed Les mœurs (The Manners, 1748), for example — Diderot hid or downplayed the full extent of his anonymous publications. One imagines how hard it would have been to admit to being the author of a disgraceful work of libertine fiction like The Indiscreet Jewels.

Didier Diderot was no dupe, however. In the letter he sent back to Denis, he signaled that he knew full well why his son had found himself locked up in a “stone box” at Vincennes. He then coolly informed the prisoner that he should take advantage of his time in jail to reflect on his life. From the elder Diderot’s point of view, his son’s downfall had come from a poor use of both his education and his mind. If “God has given you talents,” he wrote pointedly, “it is not for weakening the dogma of our sainted religion.”37

But the most significant aspect of the letter was not this gentle scolding, but rather the sentiment that it was time for the errant son to come back to the family. Some of this change of heart may have stemmed from the fact that prison had, quite paradoxically, opened lines of communication that had been closed for years. Perhaps as importantly, Didier Diderot also saw his life and family slipping away in 1749. His wife of thirty-six years, Angélique, had died the previous October, at seventy-one years of age; his twenty-seven-year-old daughter, also named Angélique, had gone mad and died behind the thick limestone walls of the Ursuline convent the same year. Faced with the prospect of a far smaller family, and surely touched that his son had reached out to him despite his own pitiful circumstances, Didier Diderot extended an olive branch. Though his letter was full of admonitions, the patriarch announced that he was now happy to approve of Denis’s marriage to Toinette, assuming that he was in fact married in the eyes of the Church. He then added that he was counting on his son to allow him to meet his grandchildren.

PRISON TALES

Didier Diderot’s letter presumably reached his son in mid-September, two months into his stay at Vincennes. By this time, the prisoner’s conditions and mood had both improved markedly. Released from his cell in the château’s keep, he now had access to the garden and courtyard and had moved to more comfortable quarters. Berryer had also granted him the right to receive visits from both family members and associates working on the Encyclopédie.

Toinette traveled to Vincennes on the first day that Diderot was granted visitation rights. The four printers, who had dispatched several letters to both Berryer and d’Argenson pleading for his release, also came to discuss how best to proceed on the stalled dictionary. In the following days and weeks, Diderot also received visits from his coeditor, Jean le Rond d’Alembert, and from the artist Louis-Jacques Goussier, who had been hired to begin work on the Encyclopédie’s illustrations. What remained of his stay at Vincennes became a working jail term.

As is the case with the imprisonment of any famous person, there are stories and family folklore associated with Diderot’s time in Vincennes. Madame de Vandeul recounts how, during her father’s days in solitary confinement, he took a slate shingle off the roof, ground it up to make his own ink, fashioned a toothpick into a quill, all in order to write in the margins of Milton’s Paradise Lost. This example of prison ingenuity is entirely plausible compared with Madame de Vandeul’s account of how her father escaped from Vincennes in order to spy on his mistress of four years, Madame de Puisieux. Madeleine was apparently as concerned as anyone else about Diderot’s incarceration; shortly after he was able to receive visitors, she joined the list of pilgrims making their way to Vincennes. Hoping for a warm reunion, she was instead greeted with a jealous interrogation after Diderot noticed she was dressed far too elegantly for a prison visit. After forcing his lover to admit that she was continuing on to nearby Champigny to attend a party, Diderot was apparently so convinced that she had replaced him with another lover that, after her coach left, he supposedly slipped out of the prison and made the seven-kilometer trek on foot to Champigny to keep an eye on her. This jaunt — through the woods of Vincennes and across the Marne River — does not seem terribly likely; nor does the supposed denouement of the story, where Diderot allegedly returned to the château and confessed his temporary breakout to the Marquis du Châtelet, the governor of the prison. Regardless of his warm relationship with his genteel host, Diderot rarely came clean so readily.

Whether or not Diderot made this trip to Champigny matters very little within the overall history of his stay at Vincennes. Far more consequential were Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s trips to the prison during the fall of 1749. In The Confessions, Rousseau relates that his friend’s incarceration distressed him immensely and that, when he was able to tear himself from his work, he made the long journey on foot from Paris to Vincennes on several occasions to see Diderot. The first time that Rousseau arrived at the prison, as he tells it, he found the jailed philosophe engaged in conversation with a priest and Diderot’s coeditor, d’Alembert.38 Describing Diderot as “much affected by his imprisonment,” Rousseau writes that he was moved to tears by this reunion: “I saw only him as I entered; I made one bound, uttered one cry, pressed my face to his, and embraced him tightly, speaking to him only with my tears and sighs, for my joy and affection choked me.”39

Rousseau’s description of his emotional reunification with his friend is followed by his mythical account of how he — a budding philosophe — was struck with the idea of turning his back on the corrupting influences of knowledge and civilization, the very cornerstones of the Enlightenment project. This story begins on a hot summer afternoon when Rousseau is making his way on foot to the Vincennes prison. Exhausted and sweaty, he decides to take shelter under a tree on the side of the road, where he pulls out the Mercure de France, the era’s premier magazine for high literary and philosophical exchange. It is in the pages of this monthly periodical that Rousseau fatefully stumbles upon an essay contest proposed by the Academy of Dijon, soliciting responses to the following question: “Has the revival of the arts and sciences contributed more to the corruption or the purification of morals?”40

This was more than a question of technical progress and moral decline. The Dijon academicians were tacitly recognizing that something drastic was happening in France. While this massive country of twenty-five million people continued to be held back (compared with England) by its entrenched guilds, a rigid social system, and problems related to a crippling debt, its scientists and philosophes had nonetheless dragged the country into a stimulating phase of intellectual fervor that risked being far more radical than the more genteel forms of Enlightenment taking place across the Channel or in Holland. These intellectual and “philosophical” advances, in many people’s view, had come at a cost: philosophes including Voltaire and Diderot had not only encouraged people to separate the spheres of religion and science, but were asking them to rethink basic moral questions — such as human happiness — that had been the purview of the Church. In a world of profound change, where the “revival of the arts and sciences” had been accompanied by a tremendous amount of freethinking, the Dijon Academy’s contest seemed to cry out for a careful survey of recent achievements in painting, sculpture, music, and the sciences — alongside a few pointed remarks regarding excesses of certain misguided souls.

Rousseau had something else in mind. Describing his reaction after he discovered the Academy’s contest, Rousseau explains that “the moment I read this I beheld another universe and became another man.” By the time he arrived at the prison, he continues, “I was in a state of agitation bordering on delirium.”41 Rousseau then recounts how he and Diderot reportedly discussed this question at length during their visit and how Diderot not only encouraged him to compete for this prize, but to go forward with the contrarian “truth” that he had received while on the road to the prison, namely, that the arts and sciences had done more harm than good to humankind.42 Of this conversation, Diderot writes,

I was at this time at the Château de Vincennes. Rousseau came to see me, and while he was there, he consulted me on how to respond to the question [proposed by the Academy of Dijon]. “There is no hesitating,” I told him, “you will take the side that no one else will take.” “You are right,” Rousseau responded to me; and he set to work transforming this jeu d’esprit into a “philosophical system.”43

In the final form of his Discours sur les sciences et les arts (Discourse on Sciences and Arts, 1750), which he completed with Diderot’s help a few months later, Rousseau put forward a genealogy of ruin which traces the scientific and technical disciplines back to the vices human beings acquired when they left the state of nature: our greed, he argues, gave rise to mathematics; our unbridled ambition spawned mechanics; and our idle curiosity produced physics. Rousseau’s message was simple and compelling: the more we advance technically and intellectually, the more we regress morally. Progress is not only a mirage that humankind is foolishly chasing, it is our downfall.

Rousseau’s essay not only won the Academy of Dijon prize, but led him to produce a second and more powerful account of humankind’s fall, which he entitled the Discours sur l’origine et les fondements de l’inégalité parmi les hommes (Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men, 1755). Also known as the Second Discourse, this profoundly influential piece of speculative anthropology chronicles humankind’s unfortunate transition from the state of nature — where humans were solitary, savage, and without reason or rationality — to the time when they began to cohabitate, develop reason and language, compare themselves to others, and enter the realm of social competition and rank. From there, Rousseau demonstrates, it was only a small step to private property and social inequality, both of which could only arise in man’s newly civilized state. Diderot once again served as Rousseau’s primary reader before he published the Second Discourse. Little did he know, however, that this stunningly pessimistic understanding of history was far more than a provocative argument; it reflected a fundamental realignment in the way that Rousseau understood the “social system,” his friendships, and the way that he would henceforth relate to Diderot and the rest of the philosophes.

THE RETURN

Diderot was finally released from Vincennes on November 3, 1749, 102 days after his arrest. One of the few possessions that he brought back with him was a small edition of Plato’s Apology of Socrates (399 BCE) that he had managed to keep with him during his stay. According to Madame de Vandeul, the prison’s guards had decided not to confiscate this particular book because they could not imagine that he could read the ancient Greek. Diderot reportedly made good use of the text, translating extensive portions of the Apology during his imprisonment.

That he was able to keep Plato’s Apology must have seemed appropriate. In this book Plato recounts the trial of his mentor and his speech of self-defense; he also details how Socrates had been accused, among other things, of being an unbeliever. Later in his career, Diderot often referred to the Greek philosopher as a kindred spirit who, like himself, was ill-suited to his own bullying era. As he put it in 1762, “When Socrates died, he was seen in Athens as we [philosophes] are seen in Paris. His morals were attacked; his life slandered.” He was “a mind who dared speak freely about the Gods.”44

Despite such similarities, aspects of Socrates’ captivity diverge significantly from the account of Diderot’s stay in Vincennes. Unlike the French philosophe, Socrates remained famously resigned in the face of persecution, calmly and knowingly drinking the hemlock that ended his life. Diderot, on the other hand, was ready to do anything to gain his freedom, deliberately putting on a series of masks designed to deceive his captors. When he first arrived at the prison, he played the defiant philosophe; soon thereafter he became the suffering prisoner; by the end of his stay, he was the remorseful sycophant. Some years later, he famously justified such moral shilly-shallying as the direct result of unequal power relations. Humans, he suggested, actually have very little agency most of the time, and must strike poses depending on who has influence over them; life, in short, demands moral compromises. In Rameau’s Nephew, Diderot labeled these ethical slippages “vocational idioms.” Each occupation, in his view, tends to accept certain repeated moral lapses as established practice, and thus ethically tolerable, much in the same way that linguistic idioms — curious turns of phrase — also become commonly accepted over time. If there was one “vocational idiom” employed by the persecuted philosophe while he was in prison, it was undoubtedly duplicity, especially vis-à-vis the police.

Shortly before he was finally released from Vincennes, Diderot had his last meeting with Berryer, the lieutenant-général de police. During this encounter, the prisoner signed a statement promising to never again publish the type of heretical works that had led to his humiliating imprisonment. For the next thirty-three years, he would essentially keep his word. Part of this had to do with the fact that Diderot knew that, for the rest of his life, each time he talked in a café, met strangers in a salon, or sent a letter, he might well be under the surveillance of the city’s mouchards. And yet, if the state effectively put an end to his public career as a writer of audacious, single-authored books, Diderot nonetheless intended to disseminate the joys of freethinking even more boldly upon his release from Vincennes. The labyrinthine Encyclopédie, as it turned out, would provide just the right venue.