IV

THE ENLIGHTENMENT BIBLE

Diderot’s incarceration at Vincennes took place exactly halfway through his seventy years on earth. An unwelcome caesura, prison became the dramatic pause that gave shape and meaning to both sides of his life. Before prison, Diderot had been a journeyman translator, the editor of an unpublished encyclopedia, and a relatively unknown author of clandestine works of heterodoxy; on the day that he walked out of Vincennes, he was forever branded as one of the most dangerous evangelists of freethinking and atheism in the country.

During Diderot’s three-month imprisonment, the Count d’Argenson and his brother the marquis had looked on with amusement while this “insolent” philosophe had bowed and scraped before the authority of the state. In a diary entry from October 1749, the marquis related with glee how his brother the count had supposedly broken Diderot’s will. Solitary confinement and the prospect of a cold winter had succeeded where the police’s warnings had failed; in the end, the once-cheeky writer had not only begged for forgiveness, but his “weak mind,” “damaged imagination,” and “senseless brilliance” had been subdued. Diderot’s days as a writer of “entertaining but amoral books,” it seemed, were over.1

The marquis was only half right. When Diderot was finally released from Vincennes in November 1749, he certainly returned to Paris with his tail between his legs. Entirely silenced, however, he was not. Two years after he left prison, the first volume of the Encyclopédie that he and Jean le Rond d’Alembert were editing together appeared in print. Its extended and self-important title, which indicated a systematic and critical treatment of the era’s knowledge and its trades, promised something far beyond a normal reference work:

Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une société de gens de lettres. Mis en ordre par M. Diderot, de l’Académie royale des Sciences et des Belles-Lettres de Prusse; et quant à la partie mathématique, par M. D’Alembert, de l’Académie royale de Prusse, et de la Société royale de Londres.

Encyclopédie, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, by a Society of Men of Letters. Edited by Mr. Diderot, of the Royal Academy of Sciences and Belles-Lettres of Prussia; and, regarding the mathematical parts, by Mr. D’Alembert, of the Royal Academy of Prussia and the Royal Society of London.

Far more influential and prominent than the short single-authored works that Diderot had produced up to this point in his life, the Encyclopédie was expressly designed to pass on the temptation and method of intellectual freedom to a huge audience in Europe and, to a lesser extent, in faraway lands like Saint Petersburg and Philadelphia. Ultimately carried to term through ruse, obfuscation, and sometimes cooperation with the authorities, the Encyclopédie (and its various translations, republications, and pirated excerpts and editions) is now considered the supreme achievement of the French Enlightenment: a triumph of secularism, freedom of thought, and eighteenth-century commerce. On a personal level, however, Diderot considered this dictionary to be the most thankless chore of his life.

PARIS, 1745: THE GROUNDWORK

Though the Encyclopédie is now synonymous with Diderot, the project did not begin as his brainchild. The original idea came from a hapless immigrant from Danzig (Gdańsk) named Gottfried Sellius. Sometime in January 1745, this tall, bone-thin academic contacted the printer-bookseller André-François Le Breton to propose a potentially lucrative venture: a French translation of one of the first “universal” encyclopedias of both the arts and the sciences to be published, Ephraim Chambers’s two-volume Cyclopaedia (1728). The printer was intrigued. English-to-French translations, which could be done without paying a livre to the foreign author or printer, had become big business for his guild. Two years before, in fact, he had hired the then unknown Diderot to help translate another English reference work, Robert James’s Medicinal Dictionary (1743–45).

Le Breton agreed to meet on a subsequent occasion with Sellius and his partner, an ostensibly well-to-do English gentleman named John Mills. Mills must have initially seemed like a valuable contributor: in addition to bringing a native understanding of English to the proposed translation, he also hinted that he had the means to bankroll part of the project. Two months later, Le Breton signed an agreement with Mills that called for an augmented four-volume translation of the English dictionary, along with a fifth volume containing 120 plates.2

Preparations for the new Encyclopédie commenced immediately. Le Breton reportedly ordered reams of high-grade paper as well as a shipment of metal fonte — an alloy of lead, pewter, and antimony — for a new set of movable type.3 Working with Sellius and Mills, he also printed and distributed a grandiloquent pamphlet that solicited subscribers for the book project. To his delight, several journals, including the Jesuit Mémoires de Trévoux, quoted the leaflet’s buoyant prose verbatim: “There is nothing more useful, more fecund, better analyzed, better linked, in a word more perfect and beautiful than this dictionary. This is the present that Mr. Mills has bestowed upon France, his adopted country.”4

Mills’s gift to the French nation hardly lived up to this rhetoric. When Le Breton received examples of the work, he was furious to discover that the translation was riddled with inaccuracies and mistakes. Mills also revealed himself to be anything but a wealthy aristocrat when he began pressuring Le Breton to sign over a portion of the project’s future proceeds. The hard-nosed printer, while smallish in stature, responded with his fists and cane, beating his business partner so badly on a Saturday night in 1745 that Mills brought criminal charges.5 Le Breton answered this accusation with his own suit against Mills, whom he besmirched as a cheat and an imposter in a publicly circulated mémoire. The well-publicized Encyclopédie, it seemed, was going nowhere.6

Despite this debacle, Le Breton continued to believe in both the feasibility and profitability of the proposed Encyclopédie project. After waiting several months for the air to clear, he once again began preparations for soliciting another royal privilege. More cognizant this time of the substantial logistics and financial risks involved in producing this multivolume work, Le Breton entered into partnership with three printers — Antoine-Claude Briasson, Michel-Antoine David, and Laurent Durand — the same men who had collaborated on the publication of the multivolume Medicinal Dictionary. He also sought out a different type of general editor to replace Mills, someone who was not only French, but seasoned, and with sterling credentials. This turned out to be Jean-Paul de Gua de Malves.7 An accomplished mathematician and fellow of the Royal Society of London, the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris, and the Collège de France, the lanky and seemingly undernourished Gua de Malves signed a contract with the consortium on June 27, 1746, in front of two witnesses, the twenty-nine-year-old Jean le Rond d’Alembert and the thirty-two-year-old Denis Diderot, both of whom had been brought on to the project to edit and, in Diderot’s case, translate some of the articles.8

Gua de Malves’s involvement in the project lasted for no more than a year.9 This time the Encyclopédie was undone by the new chief editor’s irascible personality and shameful organizational skills. Like Mills before him, he, too, entered into a series of bitter disagreements with Le Breton and the other printers and ultimately left the project in the summer of 1747.10 The departure of the short-tempered geometrician would change Diderot’s life: after two months of indecision, Le Breton and the small consortium of printers officially named Diderot and d’Alembert to be the new coeditors of the Encyclopédie.

From the point of view of the four printers, d’Alembert and Diderot were as different as chalk and cheese. The celebrated d’Alembert — who had published a groundbreaking work on fluid dynamics in 1744 — could recruit among his colleagues at the Berlin Academy of Sciences, oversee articles having to do with the sciences and mathematics, and, like Gua de Malves, provide an air of institutional respectability to the project. Although he had only just celebrated his thirtieth birthday, this handsome man had already established himself as the most famous geometer in Europe. An undisputed genius who was in contact with the greatest mathematical minds of his era, d’Alembert had been chosen to become the most famous face of the Encyclopédie. The printers saw Diderot in an entirely different light. On the one hand, all of these men knew that Diderot was a workhorse. While penning his own clandestine books, Diderot had also been the lead translator of James’s substantial Medicinal Dictionary. On the other hand, Le Breton and his associates were well aware that this up-and-coming translator and writer — the former abbé Diderot — had a potentially dangerous tendency to challenge accepted religious ideas in print.11

PLANNING AT THE “FLOWER BASKET”

That someone of André-François Le Breton’s stature entrusted the biggest investment of his career to a writer with Diderot’s doubtful reputation may now seem quite odd. Unlike some of the other more daring printers operating in the 1740s — in particular, Le Breton’s partner in the Encyclopédie enterprise, Laurent Durand — Le Breton had carefully avoided controversial publication projects. This was smart business practice. Named one of the six official printers of the king in 1740, Le Breton benefited from a number of privileges, including tax breaks and a steady stream of easy-to-print royal commissions.12

Most importantly, however, Le Breton was the designated printer of the Almanach Royal, a calendar that Louis XIV had asked Le Breton’s grandfather, Laurent-Charles Houry, to begin printing in 1683. This extremely profitable reference work, which had swollen to six hundred pages under Le Breton’s editorship, included an impressive range of useful information: astronomical occurrences, saints’ days, religious obligations, and even coach departures (arrivals were less easy to predict). But most of the Almanach was dedicated to a roster of the monarchic, aristocratic, religious, and administrative notables who ruled over twenty-five million Frenchmen. As Louis-Sebastien Mercier put it, Le Breton’s little book anointed the “gods of the earth.”13 With the exception of the royal printworks located in the Louvre, one would have been hard pressed to find a bookseller or printer more thoroughly associated with the power structure of the ancien régime. Bearing this in mind, when Le Breton brought on d’Alembert and Diderot to the Encyclopédie project, he had no intention of commissioning one of the most provocative works of the century. Some of his lack of concern surely had to do with the genre of the dictionary or encyclopedia itself. While it was true that the Huguenot Pierre Bayle had printed a contentious, four-volume dictionary in 1697 that engaged very critically with Christian dogma and history, he had done so from the relative safety of Holland. The most prominent French Catholic dictionary makers (who were effectively at war with their Protestant counterparts) tended, on the contrary, to corroborate and even strengthen the era’s most traditional ideas on a given subject.14 If the Encyclopédie’s direct French antecedents — Furetière’s Dictionnaire universel, the Jesuits’ so-called Dictionnaire de Trévoux, and the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française — had been any predictor, Diderot’s and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie should have been an uncontroversial, although much larger, compendium of knowledge defining the arts and sciences.15 This, of course, was not the editors’ intention at all; the kind of dictionary that they were envisioning meant completely rethinking the way that dictionaries functioned.

JEAN LE ROND D’ALEMBERT, ENGRAVING FROM LA TOUR’S PASTEL

Much of the planning for the third attempt at producing the Encyclopédie took place about a half mile from Le Breton’s print shop, at a Left Bank “eating house” called the Panier fleuri (Flower Basket) on the rue des Grands-Augustins. Well before Diderot began work on the Encyclopédie, he had often come to this teeming quarter near the Pont Neuf — which had several boardinghouses, taverns, and cook-caterers — to meet up with Rousseau.16 At the time, both men were leading modest, if not marginal, lives. Rousseau had been living in a series of small flats across the river, near the Palais Royal, earning enough money to feed himself by copying music; Diderot, who seemingly moved from apartment to apartment every six months, was also struggling to find his way in Paris. During these days of zealous companionship, the two men even made plans to create a waggish literary magazine called Le Persifleur (The Scoffer). Twenty years later, when Rousseau looked back sentimentally at this happy time in his life, he joked sarcastically that these gatherings must have been the highlight of the week for a man who “always failed to keep his appointments,” because he never “missed a date at the Panier fleuri.”17

After Diderot became coeditor of the Encyclopédie in late 1747, d’Alembert too joined these regular meetings at the eatery. Rousseau, who had volunteered to write articles on music for the dictionary, also introduced a soft-chinned priest by the name of abbé Étienne Bonnot de Condillac into the group.

ABBÉ ÉTIENNE BONNOT DE CONDILLAC

Unlike the three other men who congregated at the Panier fleuri, Condillac would not contribute a single article to the Encyclopédie. And yet, his philosophical orientation and interests had a decisive effect on the theoretical underpinnings of the project. This became particularly true after Condillac shared a manuscript version of his Essai sur l’origine des connaissances humaines (Essay on the Origin of Human Knowledge) with the group in 1746.18 Building on Locke’s rejection of innate ideas, Condillac put forward a sweeping empiricist understanding of cognition that maintained that our senses are more than the source of the “raw material” for cognition; they also inform the way that our mind works, “teaching” us how to remember, desire, think, judge, and reason.19 Condillac’s contribution came at a critical point in the project’s prehistory. Though the Catholic priest preferred as a matter of policy to give a wide berth to the Encyclopédie’s heterodoxy, he had nonetheless focused his friends’ gaze on the critical relationship between theories of mind and a proper scientific approach to the study of the exterior world. This would turn out to be one of the foundations of the Encyclopédie project: replacing a theologically compatible theory of cognition with one that had little room for either the soul or an innate awareness of God’s existence.20

PROMOTING THE ENCYCLOPÉDIE

During these anxious years before the first volume of the Encyclopédie finally appeared, Diderot and d’Alembert spent much of their time poring over the era’s dictionaries and reference works. In addition to identifying the headwords for which they would need to commission articles, the coeditors needed to sketch out what they believed to be the myriad relationships between tens of thousands of possible entries. Thinking through the entire project before delegating their first article, for fear of missing a cross-reference, may have been the most punishing aspect of the Encyclopédie in the early days.

In addition to determining the scope and content of the project, and how exactly to proceed, the coeditors participated in an equally critical venture — attracting subscribers. In the early months of 1750, shortly after his return from Vincennes, Diderot penned a nine-page “Prospectus” in which he announced triumphantly that this book would be far more than a straightforward compendium of the era’s facts and learning; in contrast to earlier dictionaries, the forthcoming Encyclopédie was described as a living, breathing text that would highlight the obvious and obscure relationships between diverse spheres of learning. This was evident in the way that Diderot defined the term “encyclopedia.” Far more than a simple circle or compass of learning — the literal meaning of the Greek enkuklios paideia — this new form of reasoned dictionary would actively examine and restructure the era’s understanding of knowledge.

At the same time that Diderot emphasized the project’s innovative qualities, he also let slip several white lies. Such were the conventions of the prospectus genre. The first of these was that the book, which simply did not exist at this point, was nearly completed: “The work that we are announcing is no longer a work to be accomplished. The manuscript and the drawings are complete. We can guarantee that there will be no fewer than eight volumes and six hundred plates, and that the volumes will appear without interruption.”21

This bit of creative marketing dovetailed with Diderot’s romantic account of how the Encyclopédie had come into being. In contrast to previous dictionaries or compendiums, he explained, he and d’Alembert had selected an international team of specialists who were experts in their field. The era of the dabbler and the dilettante, he implied, was over:

We realized that to bear a burden as great as the one [d’Alembert and I] had to carry, we needed to share the load; and we immediately looked to a significant number of savants…; we distributed the appropriate piece to each; mathematics to the mathematician; fortifications to the engineer; chemistry to the chemist; ancient and modern history to a man well versed in both; grammar to an author known for the philosophical spirit that reigns in his works; music, maritime subjects, architecture, painting, medicine, natural history, surgery, gardening, the liberal arts, and the principles of the applied arts to men who have proved themselves in these areas; as such each person only [wrote on] what he understood.22

To be fair, not all of what Diderot asserts in this 1750 “Prospectus” was untrue. As the project gained momentum, d’Alembert and Diderot convinced more than 150 so-called Encyclopédistes to provide articles. Forty came from the fields of natural history, chemistry, mathematics, and geography; another twenty-two were doctors and surgeons; and twenty-five more were poets, playwrights, philosophers, grammarians, or linguists. Diderot and d’Alembert also commissioned fourteen artists, a group which included engravers, draftsmen, architects, and painters.23 Some of these specialists ultimately produced large portions of the Encyclopédie. Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton, the keeper of the king’s natural history cabinet, provided almost one thousand articles on the world’s botanical specimens, minerals, and animal life. The famous Montpellier doctor Gabriel-François Venel illuminated over seven hundred topics, ranging from constipation to the forced evacuation of the stomach. Guillaume Le Blond, a military historian and tutor to the king’s children, wrote some 750 articles, among them dissertations on battlefield strategies, military tribunals, and the various rituals associated with a victory. The renowned legal expert Antoine-Gaspard Boucher d’Argis would ultimately produce four thousand articles ranging from one documenting a plaintiff’s legal recourse after a dog bite to the definition of and punishments for committing sodomy.

And yet, during the first years of Encyclopédie production, Diderot was the motor of the project. Although the title page of the first volume of the work proudly proclaims that the book was being produced by a “Society of Men of Letters” (with eighteen named contributors), he was ultimately obliged to write two thousand articles for this first tome on subjects as varied as geography, childbirth, botany, natural history, mythology, carpentry, gardening, architecture, geography, and literature.24 He found himself similarly burdened for the second.

MIND AND METHOD

While Diderot was furiously writing articles for the first two volumes of the Encyclopédie, d’Alembert was engaged in producing one of the most celebrated texts of the French Enlightenment, the “Discours préliminaire” (“Preliminary Discourse,” 1751). Serving as the primary introduction to the Encyclopédie, this manifesto signaled a dramatic shift in Europe’s cultural and intellectual landscape.

In the first section of the “Discourse,” d’Alembert explains how he and Diderot planned to categorize the tens of thousands of articles that the dictionary would ultimately contain. Implicitly rejecting any a priori categories or authorities, d’Alembert proposes what we might now call a mind-based organization of human knowledge. Beginning with the basic Lockean notion that our ideas arise solely through sensory contact with the exterior world, the mathematician then associates three forms of human cognition with their corresponding branches of learning. Borrowing this idea directly from the English philosopher, statesman, and scientist Francis Bacon and his 1605 Advancement of Learning, d’Alembert asserts that our Memory gives rise to the discipline of History; our Imagination corresponds to the category of Poetry (or artistic creativity); and our ability to Reason relates to the discipline of Philosophy.25 In addition to creating the three major rubrics under which all the book’s articles would supposedly be organized, this tripartite breakdown established an entirely secular foundation for the web of knowledge presented in the dictionary.

The second part of the “Discourse” situates the Encyclopédie project within a much larger chronicle of humankind’s scientific and intellectual achievements. After lambasting the medieval era as a millennium of scholarly and scientific darkness, d’Alembert goes on to laud the intellectual heroes of the previous three hundred years, among them Bacon, Leibniz, Descartes, Locke, Newton, Buffon, Fontenelle, and Voltaire. These leading lights, according to the mathematician, had not only combated obscurantism and superstition, but they also gave rise to a new generation of scholars and savants that was now intent on ushering in a more rational and secular era. While d’Alembert’s view of history does not advocate political upheaval by any stretch of the imagination, he was promoting what one might call an Enlightenment version of manifest destiny.

Diderot republished two companion pieces alongside d’Alembert’s “Preliminary Discourse.” The first was the aforementioned “Prospectus,” which not only specifies how the various disciplines would be treated, but provides a useful history of dictionaries. (It is also here that Diderot states, somewhat pessimistically, that, in times of despair or revolution, the Encyclopédie might serve as a “sanctuary” of preserved knowledge, akin to a massive time capsule.)26 The second document was a large foldout road map for the project, a slightly modified version of the “Système des connaissances humaines” (System of Human Knowledge) that had appeared with the “Prospectus” a year before. Graphically rendering the same breakdown of human understanding that d’Alembert described in the “Preliminary Discourse,” Diderot’s “System” paired Memory with History, Reason with Philosophy, and Imagination with Poetry. And under these cognitively based categories, Diderot spelled out the long list of subjects to be treated.

At first glance, this large map of topics, which ranged from comets to epic poetry, seems quite inoffensive. Indeed, the Encyclopédie’s earliest critic, the Jesuit priest Guillaume-François Berthier, did not quibble with how Diderot had organized the “System”; he simply accused Diderot of stealing this aspect of Bacon’s work without proper acknowledgment. Diderot’s real transgression, however, was not following the English philosopher more closely. For, while it was true that Diderot freely borrowed the overall structure of his tree of knowledge from Bacon, he had actually made two significant changes to the Englishman’s conception of human understanding. First, he had broken down and subverted the traditional hierarchical relationship between liberal arts (painting, architecture, and sculpture) and “mechanical arts” or trades (i.e., manual labor). Second, and more subversively, he had shifted the category of religion squarely under humankind’s ability to reason. Whereas Bacon had carefully and sagely preserved a second and separate level of knowledge for theology outside the purview of the three human faculties, Diderot made religion subservient to philosophy, essentially giving his readers the authority to critique the divine.

It is now somewhat difficult to pick up on the subtle yet substantial examples of heterodoxy that Diderot embedded in his “System.” To do so, one needs to do what an eighteenth-century censor would do: scan the least prominent parts of the chart in search of the most outrageous ideas. Let us look, for example, at how Diderot further mocked the notion of religion in the subsection of the tree of knowledge dedicated to the so-called Science of God.

DIDEROT’S “SYSTEM OF HUMAN KNOWLEDGE,” FROM VOLUME 1 OF THE ENCYCLOPÉDIE (DETAIL)

Already subjected to human reason, the “Science of God” breaks down into two smaller categories: the first is natural theology (belief in God as deduced from the order of creation) and the second is “revealed” theology (belief based on Holy Scripture and the supposed demonstration of divine will). Both of these rubrics are then reduced more generally to “religion.” Diderot buried his first somewhat irreverent notion underneath this rubric, indicating that religion was ultimately indistinguishable from superstition. This insulting idea — that religion and superstition were contiguous practices, not distinct categories — also appears under the second major subcategory, the “Science of Good and Evil Spirits,” where religious practice seems to bleed imperceptibly into divination and black magic. Close readers got the joke: the more one studies the so-called Science of God, the more it becomes clear that religion leads inevitably to occult and irrational practices. Indeed, within the Encyclopédie’s overall breakdown of human knowledge, the so-called Science of God could have just as easily been classified under humankind’s ability to “imagine” as its capacity to “reason.”27

THE ACCESSIBLE LABYRINTH

In their correspondence, Diderot and d’Alembert often described the Encyclopédie project as a theater of war where Enlightenment intellectuals intent on ushering in an era of social change struggled against the constant scrutiny and interference of the French Church and state. The result, from d’Alembert’s point of view, was a book that suffered from a fundamental inability to say precisely what it needed to say, especially in matters having to do with religion. Diderot was even more categorical. As he finally completed work on the last volume, he blamed the radically uneven quality of the articles on the unending compromises he was obliged to make to satisfy the censors. And yet one of the many ironies associated with the Encyclopédie is that the same conservative constituencies that succeeded in censoring and shutting down the publication of the Encyclopédie on two occasions — a story to which we will return — were partially responsible for the genius and texture of this huge dictionary. After all, it was the most repressive elements of the ancien régime that spawned the book’s brilliant feints, satire, and irony, not to mention its overall methodological apparatus and structure.

Even the most noncontroversial and seemingly benign aspect of the Encyclopédie — its alphabetical order — was chosen with this in mind.28 By organizing the book’s 74,000 articles alphabetically (as opposed to thematically), d’Alembert and Diderot implicitly rejected the long-standing separation of monarchic, aristocratic, and religious values from those associated with bourgeois culture and the country’s trades.29 In their Encyclopédie, they decided, an article on the most sacred subject of Catholicism could find itself next to an involved discussion of how brass was made. Furthermore, the arbitrary nature of alphabetical order authorized them to “orient” their reader as they saw fit, through a highly developed and subtle system of linking and cross-references.30

Through the power of the digital humanities, we now know much more than Diderot himself ever did about the network of cross-references or renvois that he and d’Alembert sprinkled throughout the Encyclopédie. In all, approximately 23,000 articles, or about one-third, had at least one cross-reference. The total number of links — some articles had five or six — reached almost 62,000.31 Early on, Diderot and d’Alembert were quite coy about the function of their cross-references in both the “Preliminary Discourse” and the “Prospectus.” But by the time that Diderot wrote his famous self-referential article on the project — the entry for “Encyclopédie” that appeared in the fifth volume in November 1755 — he had allowed himself to be more forthright about how this system of cross-references functioned.

The Encyclopédie, Diderot explains, contains two kinds of renvois: material and verbal. The material references are akin to contemporary hyperlinks: discipline- or subject-based recommendations for further study that “indicate the subject’s closest connections to others immediately related to it, and its distant connections with others that might have seemed remote from it.”32 Designed to produce a dynamic relationship between and among subjects, the material renvoi echoes the vibrant and forceful way that Diderot himself tended to think. As he put it, “at any time, Grammar can refer [us] to Dialectics; Dialectics to Metaphysics; Metaphysics to Theology; Theology to Jurisprudence; Jurisprudence to History; History to Geography and Chronology; Chronology to Astronomy; Astronomy to Geometry; Geometry to Algebra, and Algebra to Arithmetic, etc.”33 Earlier dictionaries, with the exception, once again, of Bayle’s Dictionnaire historique et critique (Historical and Critical Dictionary), generally sought to communicate a linear and singular vision of truth. This new interdynamic presentation of knowledge and cross-references had a different function: it not only highlighted unobserved relationships among various disciplines, but intentionally and blatantly put contradictory articles into dialogue, thereby underscoring the massive incongruities and fissures that existed within the era’s knowledge. Readers who followed d’Alembert and Diderot on this intellectual journey could not help but question a number of the era’s traditional convictions related to religion, morality, and politics.

In addition to these potentially thought-provoking cross-references, the Encyclopédie’s articles were interspersed with what Diderot called “verbal” links that guilefully satirized some of the era’s sacred cows, or “national prejudices.” He writes: “Whenever [an absurd preconception] commands respect, [the corresponding] article ought to treat it respectfully, and with a retinue of plausibility and persuasion; but at the same time, this same article should also dispel such rubbish and muck, by referring to articles in which more solid principles form a basis for contrary truths.”34

Some of these satirical renvois functioned quite bluntly. The article on “Freedom of Thought,” for example, pointed to Diderot’s biting entry on ecclesiastical “Intolerance,” inviting its reader to cultivate a critical viewpoint. Other references were more playful, including the renvoi that Diderot embedded in the article “Cordeliers” or “Franciscans.” This humorless entry begins with the history of the religious order before arriving at an in-depth description of the Cordeliers’ vestments, particularly their hoods; it then concludes by praising the religious order for its sobriety, piety, morals, and the great men it has produced in the service of God. The cross-reference, however, sends the reader to the article “Hood,” a comical entry where Diderot explains that a number of religious orders, including the Cordeliers, have hotly debated the type and shape of hood that their order should wear. This “fact” is followed by a fabricated story detailing how a century-long war broke out between the two factions of the Cordelier sect: “The first [faction of Cordeliers] wanted a narrow hood, the others wanted it wider. The dispute lasted for more than a century with much intensity and animosity, and was just barely put to an end by the papal bulls of four popes.”35

As satire goes, the linking of “Cordeliers” and “Hood” — which drew an implicit comparison between this ridiculous anecdote and the far more serious and insoluble debate between Jansenists and Jesuits — was comparatively mild. Less so were some of the other subject couplings that Diderot did not mention in his article “Encyclopédie.” The most famous example is the entry on “Anthropophages” or “Cannibals”: its cross-references directed readers to the entries for “Altar,” “Communion,” and “Eucharist.”

The possibility of finding such scandalous satire incited the Encyclopédie’s audience to read the book more comprehensively than one did a typical dictionary. Yet Diderot and d’Alembert were very careful not to insert such patently irreligious ideas in the most obvious places. Indeed, for potentially touchy subjects such as “Adam,” “Atheist,” “Angels,” “Baptism,” “Christ,” “Deists,” and “Testament,” the editors tended to commission orthodox articles. For the most incendiary topics, including materialism, Diderot decided to forgo commissioning or writing an article altogether.

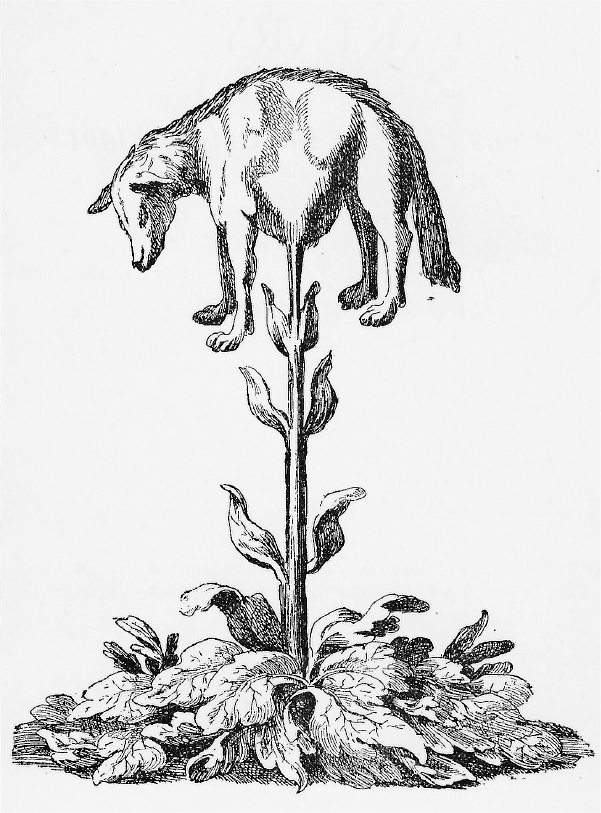

“THE VEGETABLE LAMB PLANT,” A LEGENDARY PLANT DESCRIBED IN THE ENCYCLOPÉDIE

Yet Diderot and d’Alembert certainly amused themselves by sprinkling the dictionary with irreligious notions, often within the most arcane of articles. Consider, for example, Diderot’s treatment of the Central Asian “Vegetable Lamb Plant” (“Agnus scythicus”). Commenting on claims that this massive flower supposedly produces a goatlike animal with head and hooves on its tall central stem, Diderot reminds his readers that the more extraordinary an asserted “fact” may be, the more one must seek out witnesses to confirm it. Few readers would have misunderstood what Diderot was talking about when he concluded that all such miracles, which always seem to be witnessed by only a few people, “hardly deserve to be believed.”36

Diderot and d’Alembert also encouraged another form of satire, commissioning articles whose stodgy and earnest conformism provided their own form of mockery. Such was the case for abbé Mallet’s plodding, five-thousand-word assessment of “Noah’s Ark,” a creationist account of the world that enters into absurdly laborious detail about the amount of wood used for the great ship, the number of animals saved (and those to be slaughtered for meat), and the system of manure disposal needed for the thousands of creatures aboard. Whether Mallet realized it or not, his explications of traditional Church doctrine not only bog down under the weight of their own improbable and contradictory assertions, but raise far more questions than they resolve.

Not all articles employed such oblique irony. Sometime in 1750, Diderot wrote a provocative entry on the subject of the human âme (soul) that he appended to a much longer article on the same subject, written by the Christian philosopher abbé Claude Yvon. Yvon’s article, which Diderot himself had commissioned, gives a massive, 17,000-word history of the concept of the soul that includes frequent attacks against Spinoza, Hobbes, and the threat of materialism. From Yvon’s Cartesian point of view, the soul is linked to God and, like the deity, is immaterial and immortal; and only humans, as opposed to animals, are blessed with this incorporeal essence. One suspects that, against his better judgment, Diderot simply could not let this lengthy dissertation stand without some sort of rebuttal.37

In his supplementary article, which the Jesuits attacked immediately upon its publication, Diderot did not get bogged down in abstruse theological questions. Instead, he asked a far simpler question: if the immaterial soul is supposedly the seat of consciousness and emotion, where does it connect to the body? In the pineal gland, as Descartes had asserted? In the brain? In the nerves? The heart? The blood?38 Drawing attention to theology’s inability to answer this question, he then went on to demonstrate that the supposed immateriality of consciousness — and the soul — was more tied to the physical world than many people believed. If someone is delivered poorly at birth by a midwife, has a stroke, or is hit violently on the head, says Diderot, “bid adieu to one’s judgment and reason” and “say goodbye” to the supposed transcendence of the soul.39 Diderot’s critics understood perfectly well what the philosophe was saying in this article: the true location of the soul is in the imagination.40

The only other subject more problematic than religion was politics. In a country without political parties, where sedition was punished by sentencing to a galley ship or death, d’Alembert and Diderot never overtly questioned the spiritual and political authority of the monarchy. Yet the Encyclopédie nonetheless succeeded in advancing liberal principles, including freedom of thought and a more rational exercise of political power. As tepid as some of these writings may seem when compared with the political discourse of the Revolutionary era, the Encyclopédie played a significant role in destabilizing the key assumptions of absolutism.

Diderot’s most direct and dangerous entry in this vein was his unsigned article on “Political Authority” (“Autorité politique”), which also appeared in the first volume of the Encyclopédie. Readers who chanced upon this article immediately noticed that it does not begin with a definition of political authority itself; instead, it opens powerfully with an unblemished assertion that neither God nor nature has given any one person the indisputable authority to reign.41

POLITICAL AUTHORITY: No man has received from nature the right to command other men. Freedom is a gift from the heavens, and each individual of the same species has the right to enjoy it as soon as he is able to reason.42

“Autorité politique” did more than simply challenge the idea that a monarch derives his political legitimacy from the will of God. Anticipating what Rousseau would write several years later in the much more famous Discourse on Inequality (1755), Diderot goes on to recount the origins of political power and social inequality as arising from one of two possible sources, either “the force or violence” of the person who absconded with people’s freedom, which was Hobbes’s view, or the consent of the subjugated group through established contract, which came from Locke. While Diderot does not contradict the right of the French kings to rule directly — he later goes on to praise Louis XV — he also puts forward the perilous idea that the real origin of political authority stems from the people, and that this political body not only has the inalienable right to delegate this power, but to take it back as well. Forty years later, during the Revolution, the most incendiary elements of “Autorité politique” would provide the skeleton for the thirty-fifth and last article of the 1793 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which asserted not only the sovereignty of the people, but the right to resist oppression and the duty to revolt.

THE VISUAL ENCYCLOPÉDIE

The most intriguing facet of the Encyclopédie is the artful ways in which its editors engineered the dissemination of subversive ideas — be it in a self-imploding article on theology or a satirical cross-reference. Yet the vast majority of its entries lacked even a trace of irony. At the heart of the Encyclopédie are tens of thousands of straightforward articles in fields including anatomy, architecture, astronomy, clock making, colonial practice, gardening, hydraulics, medicine, mineralogy, music, natural history, painting, pharmacology, physics, and surgery. Much of what is contained in this collective inventory of the era’s learning is politically neutral compared to the Encyclopédie’s anticlerical or political commentary. And yet this massive flood of information reflects what is perhaps the Encyclopédie’s ultimate political act: the overturning of established orders of knowledge.

Nowhere was this truer than in the representation of the era’s major trades and occupations, which are sumptuously depicted within the Encyclopédie’s eleven volumes of planches, or illustrated plates. These illustrations begin, in volume 1, with several bucolic scenes of domestic agriculture; they conclude, almost three thousand images later, with a stunning series of schematic drawings of the silk loom. This far-reaching inventory of craftsmanship and technical knowledge — which includes trades as varied as pin making, boot making, and ship construction — not only elevated the era’s occupations and crafts to new heights, but helped redefine the scope of what encyclopedias could and should endeavor to accomplish.43

As originally conceived, the illustrated portion of the Encyclopédie was supposed to be something of a supplement, a visual compendium of several hundred images.44 In its final form, however, the plates became as crucial to the overall project as the text itself. The lore associated with the production of these engravings conjures up Diderot at his most dynamic and polymathic, flitting about Paris from workshop to workshop, interviewing tradesmen, translating their technological knowledge into high French, and creating models of their machines. Diderot himself gave this impression in the “Prospectus”: “We took pains to go into their workshops, to ask them questions, to take down what they said and develop their thoughts, to use the terms specific to their professions, to lay out the tables and diagrams…and to clarify, through long and frequent interviews, what others had imperfectly, obscurely, and sometimes unreliably explained.”45

While it is certainly true that this Langres-born son of a master cutler took an active interest in certain trades — he was apparently fascinated by a stocking machine model that he kept at his desk — it seems that Diderot played up his involvement with the tradesmen. His later correspondence indicates that he spent most of his time during the 1750s and 1760s in editorial mode, while the real work on the plates was delegated to a series of illustrators, chief among them Jean-Jacques Goussier.

Goussier, who is among the greatest unsung heroes of the Encyclopédie, signed onto the project in 1747. Acting under Diderot’s supervision, the illustrator toiled alongside a relatively small team of draftsmen for twenty-five years, producing well over 900 of the 2,885 illustrations.46 The labor involved in this process is, by contemporary standards, inconceivable. To begin with, many of the subjects treated in the plates necessitated an enormous amount of preliminary research before the first proper sketch was made. Goussier himself reportedly spent six weeks studying paper making in Montargis, a month studying how anchors were made in Cosne-sur-Loire, and six months in Champagne and Burgundy studying ironworks and the complicated manufacture of mirrors.

Once Goussier and his fellow illustrators (who included Benoît-Louis Prévost, A. J. de Fert, and Jacques-Raymond Lucotte) had produced refined drawings, they turned them over to Diderot, who signed off on each illustration with a short note indicating that they were ready to be engraved (bon à tirer).47 Approved drawings then moved on to the engravers, who were responsible for transposing the sketches onto folio-sized copper plates.

DIDEROT’S SIGNED APPROVAL TO PUBLISH

The illustrations in the Encyclopédie devoted to the process of engraving conjure up an orderly workplace.

ENGRAVER’S STUDIO

LETTERPRESS PRINT SHOP

Le Breton’s print shop on the rue de la Harpe was surely more frenzied and filthy. While the Encyclopédie’s images of printing technology certainly allow us to envision the basic steps involved in creating an engraving — heating the plate on a grill, applying the ink to the plate’s small grooves, wiping the plate so that the oily ink remains only in the incised parts, applying the paper on the plate, and finally, pressing and rolling the paper through the press — they do not reflect the scale of the Encyclopédie production itself. To produce over four thousand copies of each illustration, Le Breton’s operation often had fifty workers laboring full-time on the project — a far cry from a clinically organized room with three workers hanging sheets of paper on a line to dry.48

Whatever the working conditions of Le Breton’s workshop may have been, the illustrations that his workers produced were as beautiful as they were revelatory. Presumably acting on Diderot’s deep-seated belief that we are often deceived by exterior forms, Goussier and his team deconstructed the objects they were drawing. Thus the illustrators drew the working parts of hundreds of machines and contraptions, including windmills, sugarcane “factories,” grandfather clocks, various naval vessels, coal mines, and artillery canons, among other things. Perhaps the most revealing “demystification” was that of the fantastic theatrical machines of the Paris Opéra, whose cunning mechanical elevators and moving stages were depicted in painstaking detail.

The goal of the Encyclopédie’s plates was to pull back the world’s curtain. This tendency carried over to the presentation of the human body as well. Taking a page from Vesalius (and contemporary books of anatomy), Goussier’s illustrators produced stomach-churning renderings of the splayed, dissected, and dismembered human body. In addition to featuring images of severed and ligatured penises and full abdomenal cavity dissections, the book’s anatomical plates also highlighted recently pioneered surgical procedures such as cataract removal. These illustrations, which sometimes include the type of restraints necessary to hold down the patient, effectively convey both the wonders of surgical technique and the corresponding fear of medical treatment.

SURGICAL TOOLS

In addition to depicting the inner workings of both machines and bodies, the illustrators grouped various objects and animals according to type, size, and other similar criteria. Sets of insects, seashells, printing typefaces, marine standards, coats of arms, and even architectural columns appear in neatly arranged progressions. If the designers of these compositions were seeking to bring order to the various objects being represented, the illustrations now appear to us, paradoxically, to have lost their initial simple rationality.49 This is particularly true for the thousands of pages dedicated to long-forgotten tools, all of which are arranged with compulsive precision. Often drifting in space with little or no obvious scale or reference points, these unrecognizable instruments have outlived their original context.

Just as important as what was featured in the plates is, of course, that which does not appear. The greatest visual absence among the “trades” is one of the most lucrative of them all: the business of selling and buying enslaved Africans. Although some of the plates dedicated to colonial agriculture do feature small, bucolic vignettes of African slaves working in the French cotton and indigo industries, Diderot did not commission images of cargo ship conversions, human stowage plans, or the various forms of imprisonment that made the trade possible.50

AFRICAN SLAVES WORKING IN A SUGAR MILL

To be fair, Diderot seemed equally uninterested in portraying the often brutal conditions under which the French working class labored. If the occasional plate inadvertently conjures up the reality of the era’s laborers — in the image on this page, for example, one can see a young boy holding a pitcher into which an engraver is pouring acid — the intent of the editors and the artists was hardly to raise consciousness about the plight of either slaves or the workhands who made the country function. On the contrary, the Encyclopédie’s objective was to portray an idealized and aestheticized view of human ingenuity, effort, and industry, especially when it resided among the lower classes. The point of view reflected in the Encyclopédie’s plate volumes is, in many ways, that of the proud son of a master cutler. As “political” documents go, this inventory of trades and occupations is certainly subtler than what is contained in the Encyclopédie’s letterpress volumes. Yet the seemingly unthreatening and informative nature of the illustrations, like the whole of the dictionary itself, nonetheless hints at the latent political aspirations of the Third Estate, several decades before the Revolution.