VIII

ON THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES

In the final paragraphs that Diderot wrote for his review of the Salon of 1769, the philosophe explained why he thought that the best days of the biennial were over. Tastes, he believed, were changing, and not for the better. Younger Parisians now had less appreciation for the fine arts, philosophy, poetry, and traditional sciences; they were far more preoccupied with “administration, commerce, agriculture, imports, exports, and finance.” While the philosophe did not dispute what he called “the beauty of the science of economics,” he also lamented that this trend would eventually transform his countrymen into “morons.” Money, in his opinion, was the enemy of human imagination. Great artists (and true aficionados like himself) understood this: not only did they scorn art’s financial value, they became so obsessed with the quest for the perfect canvas or statue that they tended to become “unspeakably neglectful” of their own private lives.1

Not surprisingly, Diderot’s assessment of the Salon of 1769 was shorter than that of either 1765 or 1767. This was not only the art’s fault. In addition to the fact that Diderot now found far fewer paintings and sculptures that inspired him, he was thoroughly occupied with writing a beguiling and unpublishable piece of science fiction recounting the godless origin of the human species. Diderot had first gotten the idea for this text during a dinner party in August 1769 at the so-called Synagogue, a sumptuously appointed four-story townhouse on the rue Royale belonging to his friend Paul Henri d’Holbach. If there was one place in Paris where Diderot would have been able to speak with impunity about such heretical ideas, it was at this temple of impiety, just north of the Louvre.2

BARON D’HOLBACH, ENGRAVING

D’Holbach, who had inherited two immense fortunes from his father and uncle, purchased this imposing building in 1759, and transformed it into the greatest freethinking salon of the eighteenth century. On virtually every Thursday and Sunday afternoon when he was not at his country estate at Grandval, the baron (and his coquettish wife) invited between fifteen and twenty-five people to his house for conversation and a multicourse feast.3 In addition to Diderot, who was one of the regulars, guests included Grimm, Buffon, Condillac, Condorcet, d’Alembert, Marmontel, Turgot, La Condamine, Raynal, Helvétius, Galiani, Morellet, Naigeon, Madame d’Épinay, Madame d’Houdetot, and Madame de Maux. Quite frequently, the baron also welcomed illustrious foreigners on Sundays, including Adam Smith, David Hume, Laurence Sterne, and Benjamin Franklin. Invitees knew the ritual well. Meals began at two p.m. sharp and ran until seven or eight p.m.; exquisite fare and superb wines were always on the menu; and anyone who came to the rue Royale was encouraged to engage in unbridled freethinking and debate. What was discussed at the so-called hôtel des philosophes stayed at the hôtel des philosophes.

All was not simply cuisine and chitchat behind the walls of d’Holbach’s townhouse, however. As well as organizing his celebrated gastronomic salon, the baron financed and presided over an enormous and clandestine atheism factory. Drawing inspiration and material from the extensive three-thousand-volume library that he maintained on the premises, d’Holbach wrote, translated, and collaborated on more than fifty books, about ten of them with provocative and anticlerical titles like Christianity Unveiled (1761), The Sacred Contagion (1768), Critical History of Jesus Christ (1770), and System of Nature (1770).4 Though Diderot wisely left no traces of his own participation in these projects, it is evident that he contributed at least marginally to some of the attacks that d’Holbach levied against the Church. This was particularly true for System of Nature, one of the best-selling works of atheism ever published.

Despite his support for the baron’s scorched-earth campaign against all forms of spirituality, Diderot was far less interested than d’Holbach or his disciple, Jacques-André Naigeon, in disseminating straightforward atheism by the 1760s and 1770s. Rather than contradicting Scripture or trumpeting godlessness — especially in print — Diderot generally preferred thinking through the problems that remained unanswered after atheism was established as a given. These far headier questions began with What is life? and extended to natural history puzzles such as Who are we? Where did we come from? How are we changing as a species, both morally and physically? And can matter actually think?

Diderot had been asking questions such as these one afternoon at d’Holbach’s house when, according to his own description of events, he and a number of irreverent dinner guests began making jokes about the first humans. One can imagine the guffaws as someone directed the conversation to the contents of Eve’s ovaries and Adam’s testicles. Were the organs of these first-generation humans normal? Or were they swollen with the seeds of all future generations, compressed into smaller and smaller spores, like matryoshka dolls? After the dinner wound down and the guests had all left, Diderot lingered. It was at this point that he and d’Holbach perhaps shared a glass of Malaga — d’Holbach often served his friend this prized dessert wine — while discussing a series of related and far more serious subjects including the birth of new types of animals, the natural history of the human species, and the likely destruction and revival of the world.5 The speculative biology discussed that night did not dissipate with the wine. Over the course of the next month, Diderot wrote three short dialogues, the sum of which constitute the most engaging proto-evolutionary book of the eighteenth century.

D’ALEMBERT’S DREAM

The August 1769 heat wave numbered among the most oppressive that Diderot could remember. Toinette and Angélique had already fled the summer heat in July, preferring the riverbanks of Sèvres to the sweltering Faubourg Saint-Germain. Most of the philosophe’s friends were also avoiding the capital: d’Holbach had retreated to Grandval; Grimm was traveling to various courts in Germany; and the Volland sisters had settled into life at their family château, near Vitry-le-François. Diderot, however, remained in Paris, submerged in work. Every morning, after breakfast, he climbed the stairs from his apartment to the sixth-floor office, where he wrote under the building’s rafters and slate roof. Spending time in this stifling atticlike atmosphere had only one advantage: unlike the tenants on the first and second floors, he was not privy to the foul stench of the street.

Much of what Diderot needed to accomplish that summer involved a tremendous amount of editing. In addition to being surrounded by illustrations “from head to foot” as he proofed the copy for the sixth volume of plates, he had also temporarily inherited the unpleasant chore of reviewing a number of books for the Literary Correspondence while Grimm was in Germany. (He described this as writing some “pretty good things about some really bad ones.”)6 His final task was to polish one of the most modern economic treatises of the era, Abbé Galiani’s Dialogues sur le commerce des blés (Dialogues on the Commerce of Wheat). In the midst of all this editing, however, Diderot somehow managed to compose D’Alembert’s Dream.

By August 31, he announced to his lover Sophie Volland that he had begun doing what he had really wanted to do: transforming his thoughts from his silly evening at d’Holbach’s into a series of outrageous philosophical dialogues.7 When he had first thought about casting characters for this discussion, he considered assigning the two major roles to the pre-Socratic philosophers Democritus and his mentor Leucippus. At first glance, these ancient Greek thinkers had seemed like excellent intellectual surrogates; like Diderot, they believed the world could only be explained as the result of physical forces, matter, and chance.

As Diderot began composing the Dream, however, he came to the conclusion that this classical framework would hinder the discussion. Having spent thirty-five years following advances and debates in the contemporary life sciences, he ultimately decided to delegate his ideas to present-day thinkers instead. Democritus, Leucippus, Hippocrates (and ancient Greece in general) soon gave way to a series of imagined Left Bank conversations between people Diderot knew in real life: d’Alembert, Mademoiselle de l’Espinasse (d’Alembert’s would-be lover), the eminent doctor, physician, and philosophe Théophile de Bordeu, and, in the first dialogue, Diderot himself.

As the curtain opens on this three-act materialist drama, we join the fifty-five-year-old Diderot and the similarly middle-aged d’Alembert in the midst of an intense debate. The rendition of Diderot that we see here differs markedly from the tepid version of the philosophe who took the stage in Rameau’s Nephew. Closer to the real Diderot, this is a far more commanding thinker, a projection of the man known throughout Paris as one of the most forceful conversationalists of his generation. And, true to form, this particular version of Diderot is bullying his friend, d’Alembert, in an imagined clash of Enlightenment geniuses.

Diderot’s goal in this conversation is quite straightforward: to convince his friend — the mathematical prodigy, illustrious member of the Académie des sciences, winner of the Berlin Academy of Science prize, member of the Académie française, and former coeditor of the Encyclopédie project — to accept an entirely materialist understanding of the universe. This is a world, Diderot points out, where everything that exists, from the movement of the stars to an idea that flits across our consciousness, is composed of or the result of the activity of matter.

The first step toward accepting this philosophical doctrine, from Diderot’s point of view, involves admitting that there simply is no valid reason to continue to believe in God. As the dialogue opens between the two men, d’Alembert seems inclined to concede this point:

I grant you that a Being who exists somewhere but corresponds to no one point in space, a Being with no dimensions yet occupying space, who is complete in himself at every point in this space, who differs in essence from matter but is one with matter, who is moved by matter and moves matter but never moves himself, who acts upon matter yet undergoes all its changes, a Being of whom I have no conception whatever, so contradictory is he by nature, is difficult to accept.8

Deity or no deity, however, d’Alembert quickly points out what he believes to be a major flaw in Diderot’s system: his friend has not explained the seemingly unbridgeable gap between the immaterial and physical worlds. Echoing elements of Descartes’s theory of human existence, which distinguishes between the body (as an unthinking extension in space) and the mind or soul (which exists on an immaterial plane of being), d’Alembert challenges Diderot to demonstrate conclusively that there really is only one substance — matter.9 Prove to me, he says, that the entire world is cut from the same cloth.

To convince his skeptical friend, Diderot does not engage with Descartes’s dualism. Instead, he decides to demonstrate that all matter has a latent ability to become sensitive and, under the right circumstances, to sense and cogitate. Ever the skeptic, d’Alembert retorts that, if this is true, then “stone must feel.”10 Diderot’s reply — “Why not?” — leads to one of the most playful thought experiments in the Dream: the conversion of a stone statue into conscious human flesh.

The statue that d’Alembert proposes for this thought experiment is Étienne Falconet’s Pygmalion and Galatea, the same masterpiece that Diderot had reviewed at the Salon of 1763.11 That the two men settle on Falconet’s statue is an inside joke. In the year before he wrote the Dream, the real Diderot had engaged in a heated correspondence with his friend Falconet about the role of posterity in the creation of art.12 Diderot argued that artists produce their best works in order to speak to future generations, perhaps even from the grave. (This was what he himself was counting on.) Falconet rejected this idealistic view of the artist. Speaking from his own experience, he maintained that once his sculptures were wheeled out of his studio, he forgot about them: they were, as he put it, “pears that fall from trees, right into pastries.”13 For this reason, Falconet’s statue was an excellent choice for pulverization: after all, “the statue has been paid for, and Falconet cares very little about his present reputation and not at all about it in the future.”14

But there was an even more salient reason why d’Alembert and Diderot settled upon Falconet’s Pygmalion and Galatea: this work of art depicts the story of a statue coming to life. Such a scene not only provides an obvious thematic link to the materialist animation proposed by Diderot, but also draws attention to the boundaries that separate matter and thought, and the living and the nonliving. Just how Falconet’s statue comes alive in the Dream differs markedly from the myth of Pygmalion, however. In lieu of gentle kisses and divine intervention, Diderot engineers a multistep mechanical process that involves breaking the statue into pieces, grinding it up in a mortar, and transforming it into something that he can then eat and animalize into himself. This speculative science reads something like a recipe:

DIDEROT: When the marble block is reduced to the finest powder, I mix this powder with humus or compost, work them well together, water the mixture, let it rot for a year, two years, a century, for I am not concerned with time. When the whole has turned into a more or less homogeneous substance — into humus — do you know what I do?

D’ALEMBERT: I am sure you don’t eat it.

DIDEROT: No, but there is a way of uniting that humus with myself, of appropriating it, a latus, as the chemists would call it.

D’ALEMBERT: And this latus is plant life?

DIDEROT: Precisely. I sow peas, beans, cabbages, and other leguminous plants. The plants feed on the earth and I feed on the plants.15

By the time that Diderot has proposed assimilating the statue into his own being — demonstrating conclusively the atomic mobility of the statue’s elements — the philosophe has made his point. All molecules have the latent potential to achieve sensitivity, to move from the realm of the inanimate to what humans call “the living” and the “thinking realm.” D’Alembert is amused by this good-humored thought experiment: “It may be true or it may not,” he states, “but I like this transition from marble to humus, from humus to vegetable matter, and from vegetable matter to animal, to flesh.”16

Diderot’s next step in his argument, which is to provide an entirely materialist account of d’Alembert’s own existence, is far more disconcerting. This story begins with the very brief introduction of the mathematician’s famous unmarried birth mother, the beguiling novelist and salonnière Claudine-Alexandrine-Sophie Guérine de Tencin (1682–1749), a woman who had started out life as a nun in Geneva before renouncing her vows and moving to Paris in 1712.17 Diderot then introduces us to d’Alembert’s biological father, a libertine and artillery officer named Louis-Camus Destouches (whom Diderot refers to as “La Touche”). The final biographical element alludes to the defining aspect of d’Alembert’s early life, the fact that his mother left him as a swaddled newborn on the steps of a small church on the Île de la Cité. The rest of Diderot’s chronicle, however, is little more than a series of seminal fluids, gestational processes, and nutritive assimilation:

DIDEROT: Before taking another step forward, let me tell you the story of one of the greatest mathematicians in Europe. What was this wondrous being in the beginning? Nothing.

D’ALEMBERT: Nothing! How do you mean? Nothing can come from nothing.

DIDEROT: You are taking words too literally. What I mean is that before his mother, the beautiful and scandalous Madame de Tencin, had reached the age of puberty, and before the soldier La Touche had reached adolescence, the molecules which were to form the first rudiments of our mathematician were scattered about in the young and undeveloped organs of each, were being filtered with the lymph and circulated in the blood until they finally settled in the vessels ordained for their union, namely the sex glands of his mother and father. Lo and behold, this rare seed takes form; it is carried, as is generally believed, along the Fallopian tubes and into the womb. It is attached thereto by a long pedicle, it grows in stages and advances to the state of fetus. The moment for its emergence from its dark prison has come: the newborn boy is abandoned on the steps of Saint-Jean-le-Rond, which gave him his name, taken away from the Foundling Institution and put to the breast of the good glazier’s wife, Madame Rousseau; suckled by her, he develops in body and mind and becomes a writer, a physicist, and a mathematician.18

What is compelling about Diderot’s retelling of his friend’s life is not the fact that this abandoned child grew up to become famous, but that the animal called d’Alembert — like Falconet’s statue — is no more than a temporary assemblage of atoms arising from, and soon to return to, a bubbling, material universe.19 The process, as Diderot explains it, is as simple as it is inevitable: “[T]he formation of a man or animal need refer only to material factors, the successive stages of which would be an inert body, a sentient being, a thinking being, and then a being who can resolve the problem of the precession of the equinoxes, a sublime being, a miraculous being, one who ages, grows infirm, dies, decomposes, and returns to humus.”20

Much more powerfully than the neutral and amusing pulverization of Falconet’s statue, the literary staging of d’Alembert’s life rewrites the mathematician’s (and our) understanding of humankind’s relationship with the material world. By the end of this somewhat unnerving conversation, the doubtful mathematician informs Diderot that he has had quite enough of this exhausting repartee and will be returning to his house to go to sleep. Diderot warns d’Alembert (correctly, of course) that he will soon be dreaming about their exchange. The reverie that ensues introduces us not only to the confused biology of the sleeping mind, but also to a much more complete history of the human and the world, a history that is inaccessible to d’Alembert’s waking and skeptical mind. Once Diderot had completed this second and much longer dialogue in the last days of August, he set aside all false modesty and boasted to Sophie that “it was actually quite clever to put my ideas in the mouth of a man who is dreaming. One often has to lend an air of folly to wisdom.”21

AS D’ALEMBERT SLEEPS

Act 2 of the Dream opens with Mademoiselle de l’Espinasse at the bedside of the dreaming and apparently delirious d’Alembert. For hours, de l’Espinasse has been carefully jotting down all his garbled and seemingly irrational mutterings. While de l’Espinasse does not yet understand the torrent of ideas that she is transcribing, d’Alembert’s dreaming body is communicating the feeling of awe as he contemplates the significance of his life (or lack thereof) within a materialist universe.

D’Alembert’s dream begins precisely where he and Diderot had left off in their earlier conversation, with a reprise of his own progressive development from inert matter to responsive and conscious being: “A living point…No, that’s wrong. Nothing at all to begin with, and then a living point. This living point is joined by another, and then another, and from these successive joinings there results a unified being, for I am a unity, of that I am certain.”22

MADEMOISELLE DE L’ESPINASSE, WATERCOLOR AND GOUACHE

Metaphors and analogies flow freely as d’Alembert attempts to explain just how these diverse particles, elements, and compounds ultimately became him. Initially, he proposes that living molecules fuse together “just as a globule of mercury joins up with another globule of mercury.”23 He then shouts to Mademoiselle de l’Espinasse that progressive creation of identity is like a swarm of bees, a mass of tiny individuals that come together and communicate through various forms of tiny pinching: “the whole cluster will stir, move, change position and shape,…a person who had never seen such a cluster form would be tempted to take it for a single creature with five or six hundred heads and a thousand or twelve hundred wings.”24

When initially speaking with Diderot, d’Alembert had not taken such views of identity seriously. The dreaming geometrician, however, is far more adventurous asleep than awake, not only proposing that organs might contribute to his psychological identity, but also theorizing that a given animal might be split or divided into smaller groups of individuals according to organic subdivisions. To explain how this might happen, he once again conjures up the image of a swarm of bees that is functioning as an individual. This time, however, he proposes surgically altering the mass by cutting them apart where they were fused together, which would result in the production of new identities: “Now carefully, very carefully, bring your scissors to bear on these bees and cut them apart, but mind you don’t cut through the middle of their bodies, cut exactly where their feet have grown together. Don’t be afraid, you will hurt them a little, but you won’t kill them. Good — your touch is as delicate as a fairy’s. Do you observe how they fly off in different directions, one by one, two by two, three by three?”25

THéOPHILE DE BORDEU, ENGRAVING

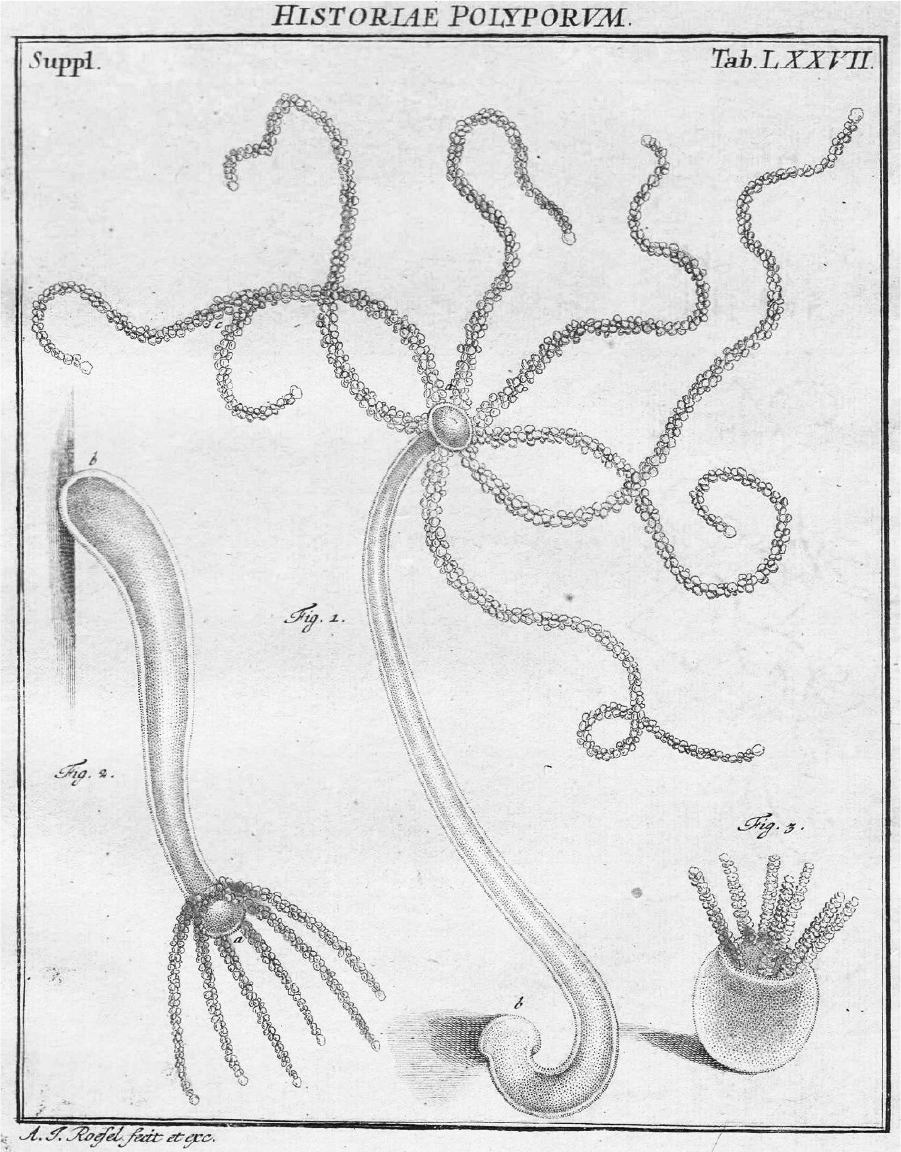

FRESHWATER POLYPS, ENGRAVING AND WATERCOLOR, 1755

Dr. Bordeu interjects that d’Alembert’s bee swarm is a very useful image; this bee animal, he points out, is akin to a massive freshwater hydra or polyp that can be cut up into smaller individuals and “that can be destroyed only by crushing.”26 That Bordeu would choose to conjure up a freshwater hydra or polyp at this point in the Dream comes as no surprise. Diderot’s generation had been fascinated with these small creatures since 1744, when the Swiss naturalist Abraham Trembley first published his “observations” on these multicellular, half-inch-long aquatic invertebrates. Adorned with a varying number of leaflike appendages, the hydra looked like a plant, yet was also quite predatory, extending its tentacles far beyond its body to coil around small crustaceans and insect larvae. Even more shocking, and of particular interest to materialists, were the polyp’s regenerative powers. Cut a hydra in half — exactly like Diderot’s swarm of bees — and two entirely new hydras would swim off. In a world where the sanctioned belief was that God had formed animals on the fifth and sixth days of Creation, here was seeming proof that life could be generated (and even self-generate) in the present.

The polyp’s asexual reproduction is hardly scandalous to modern-day scientists or theologians. Yet the hydra’s stunning ability to self-perpetuate posed a seemingly unsolvable problem to theologically oriented savants who subscribed to preformationism, which was the prevailing (and scripturally compatible) understanding of “generation” or reproduction at the time. Handed down to eighteenth-century naturalists from ancient science, the belief that all beings developed from miniature versions of themselves (“seed germs”) gained scientific currency during the seventeenth century thanks to the work of the “microscopists” Marcello Malpighi and Jan Swammerdam. Studying spermatozoa, both men published tremendously influential studies asserting that these small swimming “individuals” were complex enough to have souls. Egg-oriented anatomists working on human ova reached similar conclusions, positing that the location of the soul could be found in the human egg. Whether spermist or ovist, however, all preformationists believed that reproduction was the extension of a single act of Creation that had produced — all at once — generations and generations of homunculi (Latin for “tiny men”) or eggs. This theory was pushed to its logical, albeit absurd, conclusion, when the celebrated philosopher, priest, and theologian Nicolas Malebranche asserted, in De la recherche de la vérité (Search after Truth, 1674–75), that each egg must contain all future generations within it.

D’Alembert, who channels Diderot’s own view of “generation,” implicitly refutes this religion-tainted embryology.27 Indeed, his polyp-based understanding of procreation allows him to fantasize that humans on faraway planets might “reproduce” by “budding,” exactly like a hydra. D’Alembert lets out “bellows of laughter” as he relates this flight of the imagination: “Human polyps in Jupiter or Saturn! Males splitting up into males and females into females — that’s a funny idea…”28 As is often the case throughout the dream, d’Alembert’s mutterings underscore the remarkable fertility of nature. But they also give rise to what was an unthinkable idea at the time: the use of technology to intervene in the production of human specimens. Anticipating a form of embryo storage, d’Alembert first proposes that scientists might collect these dividing human hydras for future use. The result would be “myriads of men the size of atoms which could be kept between sheets of paper like insect-eggs, which…stay for some time in the chrysalis stage, then cut through their cocoons and emerge like butterflies.” This spawn, d’Alembert claims, might even produce “a ready-made human society, a whole province populated by the fragments of one individual…”29

This clonelike propagation fantasy bleeds into yet another of Diderot’s remarkably prescient ideas. Still visualizing the possibility of divisible humans, d’Alembert proposes distilling specific genetic types from “tendencies” located within a particular part of the body. Cackling uncontrollably at this point, the mathematician immediately seizes upon the humorous image of a new breed of humans whose character and traits would be derived exclusively from either the male or female sex organ: “doesn’t the splitting up of different parts of a man produce men of as many different kinds? The brain, the heart, chest, feet, hands, testicules…Oh, how this simplifies morality! A man born [from a penis]…A woman who had come from [a vagina]…”30

At this point in the discussion, the still-decorous Mademoiselle de l’Espinasse censors the specific details of what kind of people might come forth from the powerful organic drive of these indiscreet jewels. Instead, she moves on to the technology that might make this possible: a genetic storage chamber that she describes as a “warm room, lined with little phials,” each of which would contain a seed germ bearing a vocational label: “warriors, magistrates, philosophers, poets — bottle for courtiers, bottle for prostitutes, bottle for kings.”31 Such is the delightful eccentricity of Diderot’s understanding of the universe: the staggering unpredictability of nature is only matched by humankind’s ability to control it.

LUCRETIAN MUSINGS

Many of the stimulating ideas in D’Alembert’s Dream have their roots in Lucretius’s De rerum natura.32 This was not the first time that the philosophe had drawn from the Roman poet’s unpredictable, vibrant, and destabilizing understanding of nature. Lucretius’s ideas infused much of Diderot’s early writing on God, most famously in the deathbed scene that he inserted into his 1749 Letter on the Blind. In D’Alembert’s Dream, however, Diderot went further, combining the Roman’s Epicurean worldview with contemporary scientific knowledge and discoveries. Such is the case when the dreaming d’Alembert conjures up the “reality” of spontaneous generation, long considered an Epicurean touchstone. Peering into an imaginary container of macerating meat and crushed seed broth, exactly as the Irish naturalist John Needham had done in a famous experiment undertaken in 1745, d’Alembert proclaims that he can see rotting, inorganic matter sprouting to life and perishing before his very eyes. As he describes the “microscopic eels” that he sees swimming about (these were simply bacteria), he bellows excitedly that this microscopic universe contains a lesson about all life forms:

In Needham’s drop of water everything begins and ends in the twinkling of an eye. In the real world the same phenomenon lasts somewhat longer, but what is the duration of our time compared with eternity?…Just as there is an infinite succession of animalculae in one fermenting speck of matter, so there is the same infinite succession of animalculae in the speck called Earth. Who knows what animal species preceded us? Who knows what will follow our present ones? Everything changes and passes away, only the whole remains unchanged.33

Needham and Diderot, of course, were entirely mistaken about spontaneous generation. But the “reality” of this churning universe nonetheless gives rise to one of the most powerful moments in the Dream. This is when d’Alembert realizes that the human race, too, is but a fleeting occurrence within this endless invention and reinvention of nature: “Oh, vanity of human thought! oh, poverty of all our glory and labors! oh, how pitiful, how limited is our vision! There is nothing real except eating, drinking, living, making love and sleeping…”34

Diderot had no compunction about facing down the potential bleakness of his materialist worldview. He had underscored the ethical problems raised by his “own devil of a philosophy” in Rameau’s Nephew, and he certainly conjures up the emptiness of the material world in the Dream. Yet d’Alembert’s character, and the Dream as a whole, do not get bogged down in existential pathos. Indeed, immediately after the mathematician laments the lack of anything real and durable in his life, his gaze shifts from this menacing world of self-replicating eels and focuses on what is important to him in his own life: the alluring Mademoiselle de l’Espinasse. Dreaming of his companion, d’Alembert then becomes sexually excited and masturbates in front of the object of his fantasy. This comical moment is, we should recall, recounted by de l’Espinasse herself, who is entirely unaware of what is transpiring in front of her, as she diligently continues to take notes:

[D’Alembert said:] “Mademoiselle de L’Espinasse, where are you?” “Here.” Then his face became flushed. I wanted to feel his pulse, but he had hidden his hand somewhere. He seemed to be going through some kind of convulsion. His mouth was gaping, his breath gasping, he fetched a deep sigh, then a gentler one and still gentler, turned his head over on the pillow and fell asleep. I was watching him very attentively, and felt deeply moved without knowing why; my heart was beating fast, but not with fear.35

After d’Alembert’s “convulsion,” as Mademoiselle de l’Espinasse describes it, the restless mathematician finally enjoys a temporary respite for several hours. When he again begins dreaming, at two o’clock in the morning, he returns to the book’s biggest questions: Just what does it mean to be human? Where did our species come from? And who are we within the infinite contexts of space and time?

THE HUMAN STORY

Diderot was painfully aware that science had done little to illuminate the history of the human race. Such a subject simply did not lend itself to the kind of disinterested and probing empirical examination that Diderot promoted. Well into the eighteenth century, nature remained laden with inflexible, religious-inspired concepts. To begin with, there was the orthodox understanding of time, which, at least officially, maintained that animals and humans had come into existence at the time of the Creation, 5,769 years before.36 The second related notion was that animals and humans had appeared in their present forms during this biblical drama. The final, and perhaps less obvious, sacrosanct idea had to do with humankind’s supposedly exceptional place within God’s kingdom. According to Christianity’s sacred writings, man was unique on earth: he was a “rational” animal infused with a higher spiritual nature — a divinely bestowed soul — that separated him from the other beasts. Fashioned from the slime of the earth, this fallen creature nonetheless stood apart.

Diderot was one of the first to discredit all three of these Christian tenets in one work. But he was not the only person to disrupt the supposedly immutable barriers between animals and humans. By the late seventeenth century, an increasing number of anatomists began underscoring the undeniable physiological correlations between humans and the animal kingdom, particularly the great apes.37 This blurring reached a turning point in 1735 when the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus assigned humankind a spot in the world’s bestiary, right next to sloths and apes.38 The most important elements of Diderot’s proto-anthropology, however, did not stem from Linnaeus’s trenchant classification scheme; instead, they came from Diderot’s friend, the renowned naturalist Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon.

Buffon’s tremendous influence on Diderot had begun during the latter’s imprisonment in 1749. Once he had been allowed books at Vincennes, Diderot pored over and annotated the first three volumes of Buffon’s recently published Natural History. Among the key portions of this groundbreaking text was a 150-page inventory of the human species that, at first glance, appears to be a simple geographical catalogue of racial phenotypes. But behind this mapping of the world’s different “varieties,” as Buffon called them, was the theory that these dissimilar groups all came from a prototype race that mutated as it moved across the globe into different climates, ate dissimilar foods, and created new and diverse customs for itself.

COMTE DE BUFFON, ENGRAVING

Buffon, who was the keeper of the king’s garden and wrote the Natural History at the monarch’s pleasure, was extremely careful not to question or even bring up the biblical Genesis in this account. Yet his theory of human degeneration, as it was called, represented the single biggest reconceptualization of the history of the human species during the eighteenth century. People who read this best-selling account of a once unified, but now bifurcating, human race now had something far superior to the biblical tale of how Noah’s sons wandered off into the wilderness to start the different branches of the human family. They had a physical, scientific explanation of where we came from that was, from a European point of view, tremendously reassuring. After all, the prototype species that Buffon hypothesized was white. The other groups — the maligned and marginalized peoples of Africa and other antipodal regions — were thus, by definition, accidents of history.39

The version of the human degeneration story that Diderot conjured up in the Dream is even more forceful. Instead of retelling Buffon’s reassuring story of difference emerging from an archetype, Diderot (via d’Alembert’s dreaming) concentrates on what eighteenth-century naturalists believed to be the most degenerated variety of humans on the planet: the Laplanders. From d’Alembert’s dreaming perspective, this supposedly wretched and snow-dwelling branch of diminutive humans was not only misshapen, but on the verge of extinction, perhaps like the human race itself: “Who knows whether that shapeless biped a mere four feet in height, which is still called a man in polar regions, but which would very soon lose that name if it went just a little more misshapen, is not an example of a disappearing species? Who knows whether this is not the case with all animal species?”40

Anything but preordained, planned, or eternal, from d’Alembert’s point of view, the birth and the demise of the human species is no more significant than the delivery of a freakish two-headed pig.

D’Alembert’s character is the most despondent of the four voices that Diderot created for his Dream. As the math wizard progressively accepts the implications of materialism, he lets go of the reassuring (but spurious) concepts that give meaning to the human identity: individuality, species, and even the separation between what is normal and monstrous. By the end of his dream, d’Alembert has come to realize that humans come into this world as contingent flukes, lead their lives without knowing who they really are, and return to a bewildering world of matter without ever knowing why.

Bordeu and de l’Espinasse react far more creatively and cheerfully to these destabilizing ideas. During the Dream’s substantial discussion of monstrosity, for example, Bordeu does not deconstruct his own identity, but rather proposes an amusing Frankenstein-like thought experiment in teratogeny, the fabrication of monsters.41 Casting himself as something of a mad scientist, the doctor imagines intervening in the gestation process by manipulating the speculative genetic material of embryos, what Diderot calls “threads.” This prescient scene not only debunks the supposed “miracle” of conception, but foreshadows our own world, one in which scientists have claimed the right to refashion human biology at the embryonic level.

BORDEU:…Now do mentally what nature sometimes does in reality. Take another thread away from the bundle — the one destined to form the nose — and the creature will be noseless. Take away the one that should form the ear and it will have no ears or only one ear, and the anatomist in his dissection won’t find either the olfactory or auditory threads, or will only find one of the latter instead of two. Go on taking away threads and the creature will be headless, footless, handless. It won’t live long, but nevertheless it will have lived.42

As the willing assistant in this thought experiment, Mademoiselle de l’Espinasse immediately seizes upon the most important philosophical implications of what is transpiring. Considering the misshapen humans she and the good doctor are producing together, she realizes that no human endeavor — not science and certainly not religion — can even begin to understand the limits and possibilities of nature.

By the end of the Dream, Bordeu and de l’Espinasse have become our accomplices in a new and heady venture to better understand the universe through the frontiers of procreation. This openness to experiment reaches a boiling point during the last section of the Dream. In this tête-à-tête between the good doctor and de l’Espinasse (d’Alembert has finally left his bedroom on the rue de Bellechasse to have supper elsewhere), the two new friends sip sweet Malaga wine and let their imaginations run wild. Mademoiselle de l’Espinasse, in fact, has taken over as the more aggressive freethinker and is pushing the conversation to its limits. Liberated from d’Alembert’s presence, and out of earshot of the servants, she finally has the opportunity to ask a question that has been vexing her for hours: “What do you think about crossbreeding between species?”43 This query leads to an even more shocking idea: bestiality, the possibility of crossing humans with animals to produce a new race of beings.44

Bordeu is only too happy to take up this and all other racy subjects. Ridiculing the moral qualms of those people who have prevented more intensive “experimentation,” the doctor proposes the (hypothetical) creation of a new life form, a goat-human hybrid born from a human-animal coupling. After Bordeu discusses the technical aspects of engendering such offspring, de l’Espinasse directs her friend to start the process without any delay: “Quick, quick, Doctor, get to work and make us some goat-men!”45 While the couple eventually pulls back from this hypothetical trial — Mademoiselle de l’Espinasse suddenly objects that these goat-human hybrids might turn out to be unrepentant sex fiends — the two would-be empiricists have made their point: by playing with nature, one can readily prove that the human race is anything but immutable. Not only do human varieties change over time — shifting and twisting as a function of their climate and food — but the species itself can be altered, combined, and perhaps even improved. This last provocative section of D’Alembert’s Dream is far more than libertine chitchat; it mocks humanity’s supposedly special place in the universe, and invites us in the process to reconsider the eternal categories that supposedly define us, be they man and woman, animal and human, and even monstrous and normal.

In the weeks after he finished the Dream in the fall of 1769, Diderot read the manuscript aloud to a small group of his friends at d’Holbach’s estate at Grandval.46 One can only imagine how those in attendance must have whooped, in particular, at the last section. In this entertaining mixture of the lofty and the scabrous, Diderot had put forward a purely materialist understanding of human sexuality that explored questions related to masturbation, homosexuality, and even bestiality. Outraged, amused, or cowed into silence, what Diderot’s audience could not understand in 1769 was that, in addition to everything else, the philosopher was something of a prophetic sexologist as well.