Epilogue

WALKING BETWEEN TWO ETERNITIES

In mid-December 1776, the eighty-three-year-old Voltaire pulled out a piece of paper and dashed off a note to Diderot. Having been exiled from Paris for more than twenty-five years, the now wizened and virtually toothless philosophe lamented the fact that the two men had never laid eyes on each other: “I am heartbroken to die without having met you…I would gladly come and spend my last fifteen minutes in Paris in order to have the solace of hearing your voice.”1

Fifteen months later, Voltaire rolled into the capital in his blue, star-spangled coach. Quite ill with prostate cancer, the famous humanitarian, essayist, and playwright nonetheless organized a feverish schedule for himself. In addition to finishing work on a five-act tragedy — he lived long enough to attend the premiere — Voltaire spent most of his days holding court in a friend’s hôtel particulier on the corner of the rue de Beaune and the quai des Théatins. Here, for hours at a time, Voltaire received visits from a long list of adoring friends and dignitaries, among them Benjamin Franklin and his son. Sometime during Voltaire’s three-month stay, Diderot also came to pay his respects. Journalists who wrote about the meeting hinted that some relationships are best conducted solely by correspondence.

HOUDON’S BUST OF VOLTAIRE

Diderot and Voltaire had first exchanged letters in 1749 when the “prince of the philosophes” had invited the then up-and-coming Diderot to dinner. In addition to hoping to get to know the clever author of the Letter on the Blind, Voltaire had presumably hoped to help the newly appointed editor of the Encyclopédie rethink his atheism. Diderot decided to dodge both the invitation and the sermon. One might wonder what kind of young writer turns down lunch with the most famous public intellectual ever to live. The answer, in 1749, was pretty clear: a proud and unremorseful unbeliever who had no interest in having his philosophy questioned by an unbending deist.

The two philosophes nonetheless remained in contact (from afar) over the course of the next twenty-eight years. Voltaire sent fifteen more letters. Diderot replied nine times. The relationship, which actually deepened as time went by, was cemented by mutual friends, mutual interests, and a deep reciprocal respect for each other’s intelligence. And yet, well into the 1760s, a continued sense of wariness existed on both sides. In addition to their divergent views on religion — Voltaire remained a Newtonian deist whereas Diderot had long declared himself an unbeliever — the two men evidently had ambivalent feelings about each other’s respective literary careers. Both had invested heavily in the theater, and each also believed that the other was on the wrong path. Voltaire, from Diderot’s point of view, continued to churn out an endless string of rearguard classical dramas and comedies; as for Voltaire, he secretly found Diderot’s bourgeois dramas to be a sad testament to the direction of the theater.

What did these two old men talk about when they finally sat in front of each other in 1778? The battles they had waged, won, and lost? The dark days of the Encyclopédie, when Voltaire repeatedly tried to convince both Diderot and d’Alembert to drop the project? The friends who had died over the years, especially the beloved Damilaville? Voltaire’s failed attempt to get Diderot elected to the Académie française? Their mutual friend Catherine the Great? Diderot’s curious book on Seneca? His secret contributions to Raynal? Or how much Diderot was in deep admiration for Voltaire’s defense of the family of the Protestant Jean Calas, who had been falsely accused of killing his son after he converted to Catholicism?

The only real accounts we have, alas, focus on an argument that the two men had regarding the merits of Shakespeare. Convinced of the superiority not only of French theater but of his own art, Voltaire supposedly asked Diderot how it was possible to “prefer this tasteless monster to Racine or Virgil.”2 In the discussion that ensued, Diderot conceded that the playwright lacked the polish of some of the greatest poets, but that the Englishman nonetheless possessed a sublime energy that transcended the “gothic” aspects of his writing. He then went on to compare Shakespeare to the massive fifteenth-century statue of Saint Christopher that stood just outside the doors leading into Notre Dame Cathedral. While perhaps crude and rustic, this colossus was very much like Shakespeare, according to Diderot, because “the greatest men still walk through his legs without the top of their head touching his testicles.”3 The implication was clear. Voltaire, who rightly considered himself the greatest French poet and playwright of his generation, did not measure up either. According to one journalist’s account of this exchange, Voltaire was not “excessively happy with Monsieur Diderot” after this comment.4

Diderot’s unrestrained tongue had reportedly irked Voltaire as much as it had captivated him. After years of exchanging letters — with Diderot, the epistolary mode had the distinct advantage of allowing the other person to respond without being interrupted — Voltaire had finally witnessed the Encyclopedist’s legendary ability to leap from one idea to the next without stopping to take a breath. After Diderot left the quai des Théatins, Voltaire reportedly remarked to some friends that his visitor had lived up to his reputation as a tremendous wit, but that nature had refused him “an essential talent, that of true conversation.”5 Diderot, too, summed up his meeting with the brilliant yet failing Voltaire. He reported that the man was like an ancient “enchanted castle whose various parts are falling apart,” but whose corridors were “still inhabited by an old sorcerer.”6

Diderot’s visit with Voltaire was the first and last time that these two figureheads of the Enlightenment era would see each other in person. Not long after his visit, on May 30, the old sorcerer succumbed to his cancer. This turned out to be the first of two significant deaths in 1778. A little more than a month later, on July 2, Jean-Jacques Rousseau would die as well. The story told throughout Paris was that Rousseau had felt ill after taking a morning stroll through the gardens at the château d’Ermenonville, twenty-five miles north of Paris. Upon returning to the cottage where was he staying, he nervously informed his longtime companion, Thérèse Levasseur, that he had a stabbing pain in his chest, a strange tingling sensation on the soles of his feet, and a ferociously throbbing headache. Soon thereafter, the Citizen of Geneva collapsed and died.7

Rousseau and Voltaire’s deaths signaled the beginning of an era where many more of Diderot’s close friends, associates, and enemies would also die. By 1783, all the main players with whom he had worked on the Encyclopédie — this included d’Alembert, Jaucourt, and the project’s four printers including André-François Le Breton — were gone. This ever-expanding necrology also came to include Madame d’Épinay and several of his painter friends as well, among them Jean-Baptiste Chardin and Louis-Michel van Loo. Diderot’s generation was disappearing.

WELCOMING THE NOOSE

Repeated bereavements surely contributed to Diderot’s decision to live a far simpler life during his last years. While he continued to work on a variety of projects, the philosophe consciously withdrew from the hubbub of Paris society. In addition to retreating with Toinette to the calm of his friend Étienne Belle’s house in Sèvres, Diderot also spent far more time at his daughter’s apartment, not only to see his two grandchildren, but to eat dinner and supper with the family. Madame de Vandeul’s brother-in-law, who was often at the house, provides us with a few clues about Diderot’s increasingly domestic existence in late 1778: “Monsieur Diderot comes every day to the house and sups with us. Madame Diderot remains [at the rue Taranne] and is generally quite ornery. These days she is quite distressed by the death of her little dog, who had been blind for three months. Madame Billard [Toinette’s older sister] sat on him by mistake, and broke his back. Since that moment, Madame Diderot has been berating her constantly.”8

Diderot, who surely recounted the story of Toinette’s little tragedy to his daughter and son-in-law, was indeed paying more attention to his family. His sole pleasure outside of the rue Taranne and Angélique’s apartment, as he confessed somewhat misanthropically some months later, was taking a coach to the Palais Royal every afternoon where he treated himself to a glass of ice cream at the Petit Caveau. Flavors of the day included fresh fruit, butter, almond milk, or kirsch.9

Diderot’s very limited correspondence at this time is dotted with allusions to both boredom and impending death. The end of life did not seem to worry him in the least, however. To begin with, as a disciple of both Montaigne and Seneca, he knew that the only thing one accomplished by dreading the inevitable was ruining the present. Yet more than simply accepting Montaigne’s tenet that “to philosophize is to learn how to die,” Diderot had also cultivated a thoughtful atheist understanding of life and death. In the materialist primer that he worked on well into the 1780s — the Elements of Physiology — he summed up what he believed to be the important things in life: “There is only one virtue, justice; one duty, to make oneself happy; and one corollary, not to exaggerate the importance of one’s life and not to fear death.”10

Diderot often drew comfort from his materialism. In the late 1750s, he once told Sophie that he had fantasized about being buried with her so that that their atoms might seek each other out after death and form a new being. His fiction, too, reflects the intellectual joy he took in thinking about a godless world. In D’Alembert’s Dream, his own character — “Diderot” — jubilantly force-feeds the core ideas of materialism to a fictional representation of d’Alembert, who later confronts the fact (while dreaming) that he, and the human race in general, are nothing more than cosmic accidents. Even more courageously, in Rameau’s Nephew, Diderot gave life to a character who cheerily embraces the idea that humans seem, at times, to be little more than pleasure-seeking meat machines.11

In contrast to other materialist writers, however, Diderot never forgot the compensatory and often comic aspects of the human condition. While perfectly aware of the threat that materialism presented to la morale, he preferred to let the bleakest elements of his philosophy dance joyfully in front of us, much as they did in his own mind. This is also the case in the last of his dialogue-driven experiments in fiction, Jacques le fataliste, which he was finishing in the same months that Voltaire and Rousseau both died.12 It is in this book that Diderot consciously took up the problem of existence in a materialist world.

Unlike D’Alembert’s Dream and Rameau’s Nephew, Diderot does not appear as a named character in this nested and digressive tale. Instead, the writer’s personality infuses the entire book, especially the “character” of the narrator as he attempts, and perhaps fails, to pull together a hodgepodge of anecdotes related to a manservant named Jacques and his master. To read the first words of Jacques the Fatalist for the first time is to be struck by the staggering modernity of this cheeky storyteller:

How had they met? By chance, like everybody else. What were their names? What’s it to you? Where were they coming from? From the nearest place. Where were they going? Does anyone really know where they’re going? What were they saying? The Master wasn’t saying anything, and Jacques was saying that his Captain used to say that everything that happens to us here below, for good and for ill, was written up there, on high.13

Jacques is the most joyful, lighthearted, and yet perhaps profound of Diderot’s books. In the hands of Diderot’s rascally narrator, the contingencies of life and our destiny all seem like fodder for a good laugh. And yet, despite the amusing tenor that defines this novel, the book raises some of the thorniest questions that the writer confronted within his philosophy: in a world that lacks a divine creator, where all beings necessarily obey the same mechanical rules that explain the material world, just what is human reality? And can we really consider ourselves free if what we do and what we think are necessarily preordained by our physiology and our environment?

It is the manservant Jacques who provides the doctrinaire answer to these questions, an answer that he learned from “his Captain” during his career as a soldier. Humans, according to this Spinoza-derived worldview, live out their lives with no free will. Each and every thing we do is ultimately determined by the effect of other preceding causes: we cannot be or think anything other than what is taking place in front of us in the present. To break free from this inescapable chain of events would be impossible; to do so would mean that we were actually someone else.14

Diderot never wavered from the core tenets of this determinist view of human existence.15 Yet the haphazard adventures and capricious narration that characterize Jacques seemingly work against the so-called fatalism that is at the heart of the book and, perhaps, our lives. As the master and his valet travel throughout France with no real destination in mind, they are never dragged down by Jacques’s potentially gloomy, closed shop of a philosophy. Instead, they luxuriate in their curious friendship, revel in the long and frequently interrupted story of Jacques’s loves, and are enthralled or exasperated by the bewildering people they meet along the way. What is more, Jacques never bows down before the inevitability of his destiny; his modus operandi is to act and react. In his travels, he confronts dangerous bandits in a tavern, sets off to find his master’s watch, scraps with a talkative innkeeper, and arranges for his master to fall off his horse. This is, to say the least, a tongue-in-cheek understanding of fatalism.

There are many messages that one can derive from this jolly and zigzagging story. Perhaps the most critical is that we as a species are far more than automata; we are self-conscious beings who can both manipulate the causes that determine who we are and delight in the complexity of human experience while doing so. Determinism, it would seem, has the space for action, if not total psychological freedom. One of the wonders of this book is that Diderot does not tell us this directly: we absorb this message through the act of reading and laughing, which is part of the philosophical experience.16

From the Encyclopédie on through to Jacques the Fatalist, Diderot entreats us to make the most of what Jacques calls the great scroll of life. This view of our existence certainly includes how we should greet death as well. Like many philosophers, Diderot believed that our final moments on earth define or establish, once and for all, the essence of our character. The most beautiful death, from a philosophical point of view, was of course Socrates’ suicide: the moment when the Greek philosopher triumphed over his captors and death by pleasantly greeting his accusers, drinking the hemlock, and dying simply, truthfully, and serenely.17

Diderot was so fascinated with this powerful moment in Plato’s Phaedo that he actually considered adapting it for the stage. While he never got around to writing this play, he nonetheless returned to Socrates’ belle mort one final time in Jacques the Fatalist. In a long speech that seems to arise out of thin air, the master suddenly announces that Jacques is, like Socrates, surely destined to die a philosopher’s death. “If it is permitted to read the events of the future from those of the present and if what is written up above is ever revealed to men long before it happens, I predict that…you will stick your head in the noose with as much good grace as Socrates.”18 This was also Diderot’s hope in the late 1770s and early 1780s: to die with the same equanimity as the great Greek philosopher.

1784

Sometime in mid-February 1784, Diderot presumably composed the last letter he would write. Scrawled in an unsteady, chicken-scratch hand, this one-paragraph note was destined for Roland Girbal, the copyist who had helped him compile his unpublished manuscripts for years. The tone is prickly: Diderot is clearly a bit annoyed that Girbal had not yet returned one of his plays: “And my comedy, Monsieur Girbal? You promised me that you would give it back to me soon. Keep your word because it is the only one of my manuscripts that I’m missing.”19

A week or so later, Diderot finally abandoned the task of collating his manuscripts for posterity; it was now time to focus on the unpleasant chore of dying. Being very ill was nothing new of course. As had been the case for years, his intestines continued to send him shuffling off to la garde-robe. Far more problematically, his fading, oxygen-starved heart not only triggered frequent and uncomfortable chest pain, but filled his lungs and legs with fluid. This painful dropsy, as edema was called at the time, made it hard to breathe, let alone climb five flights of stairs at the rue Taranne.

Diderot’s first real brush with death came on February 19, when a small blood vessel ruptured in one of his lungs. A stroke followed several days later. According to Madame de Vandeul, who happened to be present during this second vascular episode, Diderot quickly diagnosed the malady himself. After tripping over a sentence and realizing that he could not move his hand, he went over to a mirror and calmly put a finger to a part of his mouth that had gone slack. “Apoplexy,” he murmured. He then called Toinette and Angélique over to him. After reminding them to return some books that he had borrowed, he kissed them both goodbye, tottered over to his bed, and soon fell into a trancelike state.

Fittingly enough, the impact of this stroke did not affect what was arguably Diderot’s defining attribute: his astonishing ability to talk. In the three days and nights after the attack, Madame de Vandeul reported that her father entered into a “very sober and rational delirium.”20 Much like the scene that Diderot himself had conjured up in D’Alembert’s Dream, where a fictional representation of Mademoiselle de l’Espinasse sits at d’Alembert’s bedside as he hallucinates, Diderot’s own daughter now stood watch over her rambling father as a lifetime of erudition bubbled up from his brain: “He discoursed on Greek and Latin epitaphs and translated them for me, held forth on tragedy, and summoned up beautiful lines from Horace and Virgil and recited them. He talked throughout the entire night; he would ask the time, decide it was time for bed, lie down in his clothes and rise five minutes later. On the fourth day his delirium ceased, and with it all memory of what had taken place.”21

On February 22, while he was still recovering from his stroke, the greatest love and closest friend that Diderot had had in his life, Sophie Volland, breathed her last. Diderot had not seen her nearly as much as he had in the past, but he nonetheless shed some tears, consoling “himself by the fact that he would not survive her for long.”22

Word of Diderot’s declining health traveled quickly. As letters describing his worsening state began arriving throughout Europe, a deathwatch began. In the Netherlands, the philosopher François Hemsterhuis alerted Diderot’s Dutch friends and colleagues that the French philosophe had fallen back into his “second infancy.”23 Meister, in his capacity as the new editor of the Literary Correspondence, announced to a dozen European courts that Diderot was at death’s door. Grimm, who had become Catherine the Great’s agent in Paris, not only informed the empress of Diderot’s ill health, but requested permission to secure better quarters for the ailing philosophe, who was still living at his fifth-floor apartment on the rue Taranne.

Catherine received Grimm’s note six weeks after Diderot’s stroke. Dismayed to discover that Diderot was living in such unsuitable quarters, she chided Grimm for not acting on his own and instructed him to find a better flat for the philosophe. Five weeks later and 2,500 miles away, Grimm received the empress’s note and began seeking out a well-appointed garden-level flat for his friend.24

While Catherine and Grimm were corresponding about new lodgings for Diderot, the philosophe himself was undergoing agonizing and intrusive medical treatments. In happier years, Diderot had remarked that “the best doctor is the one you run to, but that you cannot find.”25 Now that he had lived past the time in his life where avoiding the doctor was the best course of action, the medical profession began a series of treatments that Diderot described as the “very nasty things” keeping him alive. Concerned about his water retention, physicians gave him emetics to make him throw up and bled him repeatedly (three times in one day on one occasion).26 A certain Dr. Malouet gave him herbs and cauterized his arm with a hot poker, a treatment designed to dry the liquid within the body. When his legs also began to swell, Diderot asked the famous Alsatian physician, Georges-Fréderic Bacher, to come to the house. Bacher coordinated a series of different treatments, including his own special pills and the application of “vessicatories” on the back of Diderot’s thighs and back. These painful, burn-producing plasters, which were composed of ground blister beetles or Spanish fly, actually provided Diderot with a certain amount of relief. On one occasion, Madame de Vandeul reported, the open wounds produced by this treatment actually rendered a “bucket” of fluid from his legs.27

Over the course of the next several months, Diderot’s daughter and wife fretted as they watched him decline, knowing full well that his vibrant presence would soon be only a memory. One of their worries was what would happen to the body of this declared atheist once he died. In an era where the Church had an effective monopoly on a proper burial, the Vandeul and Diderot families were only too aware that a majority of Paris ecclesiastics would be delighted to see the philosophe’s remains consigned to the voirie or garbage dump along with the city’s prostitutes and disreputable actors. How the clergy had reacted after Voltaire’s death six years earlier was clearly on everybody’s mind.

Voltaire had had the misfortune to die in the same reactionary parish where Diderot was now ailing — Saint-Sulpice. Though the famous playwright had actually signed something of a “recantation” of his irreligious behavior shortly after arriving in Paris, the archbishop of Paris ultimately wanted a more concrete proof that Voltaire had accepted the divinity of Jesus Christ. In late May, when word arrived in the parish that the writer was on his deathbed, the archbishop dispatched a doctrinaire curate from Saint-Sulpice, Jean-Joseph Faydit de Terssac, to attempt to extract a fuller revocation from the impenitent philosophe. Despite multiple solicitations, Voltaire seems to have held firm; his last words to the priest were reportedly “let me die in peace.”28 This rebuff led the Church to refuse the writer a suitable burial in one of the parish graveyards; some clergy even called for tossing his remains into a mass grave.

As it turned out, Voltaire’s larger-than-life reputation probably saved him from this humiliation. Louis XVI, who had carefully followed the aged writer’s apotheosis during his return to Paris, was surely as wary of his corpse as he had been of the living philosopher. To avoid the martyrdom that would come from any disrespectful handling of the cadaver, a coward’s compromise was ultimately arranged: namely, allowing the body to leave Paris as if it were still alive. De Terssac provided a letter certifying that the Church had relinquished any “parochial rights” over the affair. The men responsible for Voltaire’s remains also received documentation guaranteeing safe passage out of the capital. On May 31, 1778, under cover of night, Voltaire’s body was propped up in his carriage as if he were still alive and taken out of Paris. He ultimately received a full Christian burial, two days later, in Romilly-sur-Seine.29

Diderot’s soon-to-be lifeless body was likely to be in a far more precarious situation. This was already a matter of some speculation eight months before he died. In November 1783, a journalist writing for the Mémoires secrets related that the clergy was already sharpening its knives in anticipation of the infamous atheist’s death. Since, as the newspaper explained, “this atheist…does not belong to any academy, is not related to any great family, has no imposing public status in his own person, and does not have powerful associates and friends, the clergy plan on avenging themselves upon him and making his cadaver suffer every religious snub unless he satisfies the externals [by recognizing the divinity of Jesus Christ and the Christian God].”30

The pious Toinette was torn about what to do about this. While she “would have given her life for [Diderot] to be a believer,” she also wanted to prevent her husband from being coerced into accepting Christ in order to ensure himself a decent burial. At some point, she nonetheless decided that giving him the opportunity to return to the Church was worth a try. To this end, either she or perhaps the Vandeuls arranged for the same Saint-Sulpice vicar who had visited Voltaire, Jean-Joseph Faydit de Terssac, to come by the rue Taranne.

Having failed in Voltaire’s case, de Terssac was eager to convert the best-known atheist of his generation. According to Diderot’s son-in-law, who was present during some of the meetings, the abbé got on exceedingly well with the affable philosophe. (Diderot was far more tolerant of the clergy than Voltaire.) Madame de Vandeul even reported in her memoirs that Diderot and de Terssac came to an agreement regarding a shared set of moral principles.31

Accounts of these promising meetings soon reached Langres, where they generated a certain amount of hope that the godless philosophe might finally recant. By late April, however, de Terssac had gone too far, proposing that Diderot publish a short set of moral pensées that would contain a repudiation of his earlier works. According to Madame de Vandeul, Diderot categorically rejected this idea since, as he informed the curate, writing such a retraction “would be an impudent lie.”32

Shortly after this discussion, and perhaps to escape any more metaphysical pestering from de Terssac (or perhaps even his own brother, who was apparently threatening to come to Paris), Diderot suggested that they leave Paris for Belle’s house in Sèvres. Diderot and Toinette ultimately spent two months in the country, during which time the writer’s health improved a bit. By mid-July, however, they decided it was time to return to the spacious new quarters that Grimm (and the czarina) had rented for them on the rue de Richelieu.

Diderot’s final apartment occupied the entire second floor of a majestic limestone town house that was formerly known as the Hôtel de Bezons. Madame de Vandeul reported that her father was enchanted by the neighborhood and flat. In addition to the fact that he only had to climb one flight of stairs, the apartment had four massive floor-to-ceiling windows that let light cascade into a large reception room. Diderot was charmed. As Madame de Vandeul described it, he had always been lodged in hovels, but now “found himself in a palace.”33

The greatest advantage of this Right Bank flat was not its light or décor, however; it was the fact that it was situated within a few blocks of the Church of Saint-Roch, a parish with a long tradition of providing a suitable burial for writers and even philosophes: Fontenelle, Maupertuis, and even Helvétius had managed to be buried there. Soon after he arrived on the rue de Richelieu in mid-July, Diderot sensed that he, too, would soon be making the journey to Saint-Roch.

On July 30, he was sitting in the apartment when two workers arrived with a more comfortable bed that had been ordered for the philosophe. Once the workmen had assembled the frame, they politely asked its future occupant where he would like it placed. Diderot, whose morbid sense of humor was apparently still very much intact, reportedly replied, “My friends, you are giving yourself a lot of trouble for a piece of furniture that will only be used for four days.”34 That same night, Madame de Vandeul came by the apartment as she usually did to spend some time with her father, and watched contentedly as he held court with a few friends. Shortly before she left, she heard him paraphrase a famous quote from the Philosophical Thoughts that summed up his entire career: “The first step toward philosophy,” he apparently said, “is incredulity.” These were the last words she heard him say.

The next morning Diderot felt better than he had for months. After spending the morning receiving visits from his doctor, his son-in-law, and d’Holbach, the philosophe sat down with Toinette to his first proper meal in weeks: soup, boiled mutton, and some chicory. Having eaten well, Diderot then looked at Toinette and asked her to pass him an apricot.35 Fearing that he had already eaten too much, she tried to dissuade him from continuing the meal. Diderot reportedly replied wistfully: “What the devil type of harm can it do to me now?”36 Popping some of the forbidden fruit in his mouth, he then rested his head on his hand, reached out for some more stewed cherries, and died. While having anything but a heroic death à la Socrates, Diderot had nonetheless expired in a way that was perfectly compatible with his philosophy: without a priest, with humor, and while attempting to eke out one last bit of pleasure from life.

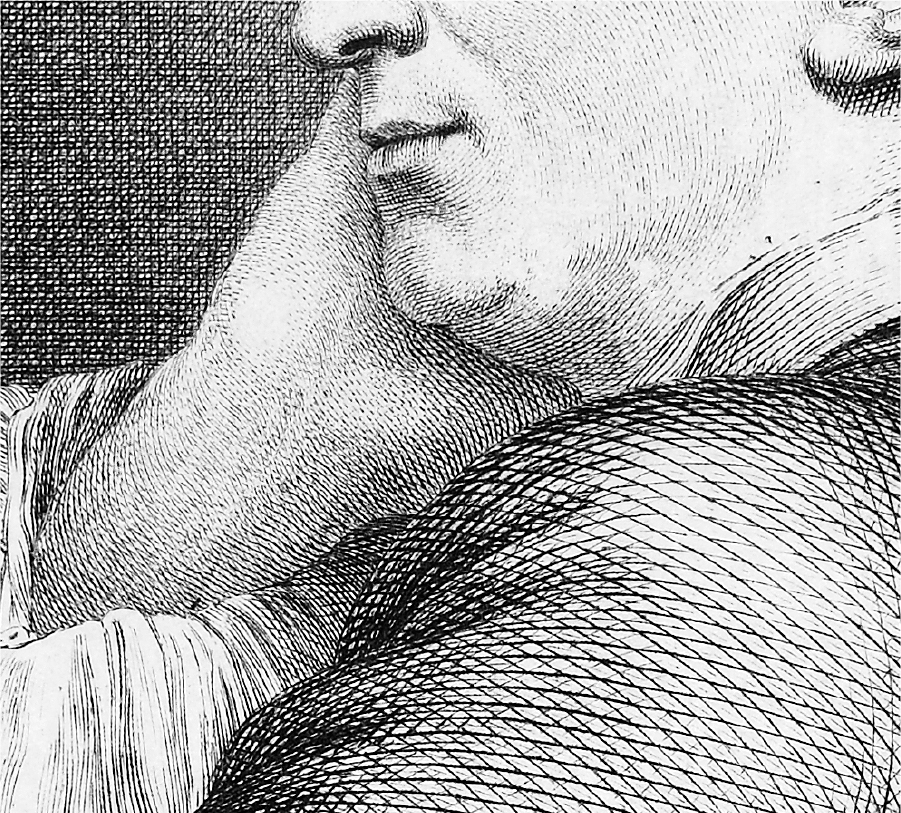

ENGRAVING OF DIDEROT AFTER GARAND (DETAIL)

The thirty-six hours after Diderot died were filled with preparations, prayers, and official visits. Upon receiving word that the ailing writer was no longer among the living, Saint-Roch’s parish priest dispatched a vicar to sit and pray with the body at the apartment. Diderot’s cantankerous old artist friend, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, also came by to sketch a memento mori of the departed philosopher, who was now lying in state. Greuze’s portrait of Diderot in death is crowlike and drawn, his nose even more prominent in death than it was in life.

DEATH PORTRAIT OF DENIS DIDEROT, DRAWING BY JEAN-BAPTISTE GREUZE

At some point after the painter had left, an autopsy was also performed on Diderot’s cadaver, something that the patient had insisted upon before he died. This dissection, according to Madame de Vandeul, generated a ghastly report summing up the various corporeal failings that had plagued her father: though his brain supposedly remained as “perfect and well conserved as that of a man of twenty…one of his lungs was filled with fluid, his heart was terribly enlarged, and his gallbladder was entirely dry, without any bile despite containing twenty-one stones, the smallest as big as a hazelnut.37

Diderot’s burial took place on Sunday, August 1. Shortly before seven in the evening, Toinette, Madame de Vandeul, Abel-François-Nicolas Caroillon de Vandeul and several other Caroillon family members descended the stairs of the apartment alongside the body of Denis Diderot. From there, the funeral cortege, which included fifty priests that the now very prosperous Vandeuls had hired, moved south on the rue de Richelieu toward rue Saint-Honoré and the Church of Saint-Roch. After the funeral mass, Denis Diderot’s lead coffin was lowered into the large central crypt under the church’s Chapelle de la Vierge. It was at this point that the long story of Diderot’s afterlife really began.

THE AFTERLIFE

In the months before he died, Diderot had prepared for what he hoped would be a postmortem afterglow. Writing for future generations, as he had revealed in the Encyclopédie article “Immortality,” had been the single biggest motivating factor in his highly policed and self-censored career: “We hear in ourselves the tribute that [posterity] will one day offer in our honor, and we sacrifice ourselves. We sacrifice our life, we really cease to exist in order to live on in their memory.”38

Diderot was far from the only writer to chase the fame that comes after death. He is, however, perhaps the only one who speaks from the grave, pleading with us to pay attention to his work: “O holy and sacred Posterity! Ally of the unhappy and oppressed; you who are fair, you who are righteous, you who avenge the honest man, who unmask the hypocrite, and who punish the tyrant; may your comfort and your steadfastness never forsake me!”39

As it turned out, posterity did not discard Diderot in the years right after his death. His naturalistic and sentimental play, The Father of the Family, continued to enjoy a strong resurgence on stages throughout France well into the 1790s. New and pirated editions of the Encyclopédie also continued to circulate throughout Europe at the same time that the editors of the new Encyclopédie méthodique were warmly crediting him for inspiring them to undertake their own massive inventory of human knowledge. And yet something dramatic would also happen to Diderot’s legacy after the French Revolution broke out in 1789; five years after this champion of human rights and freedom had died, he was increasingly being lambasted as an enemy of the people.

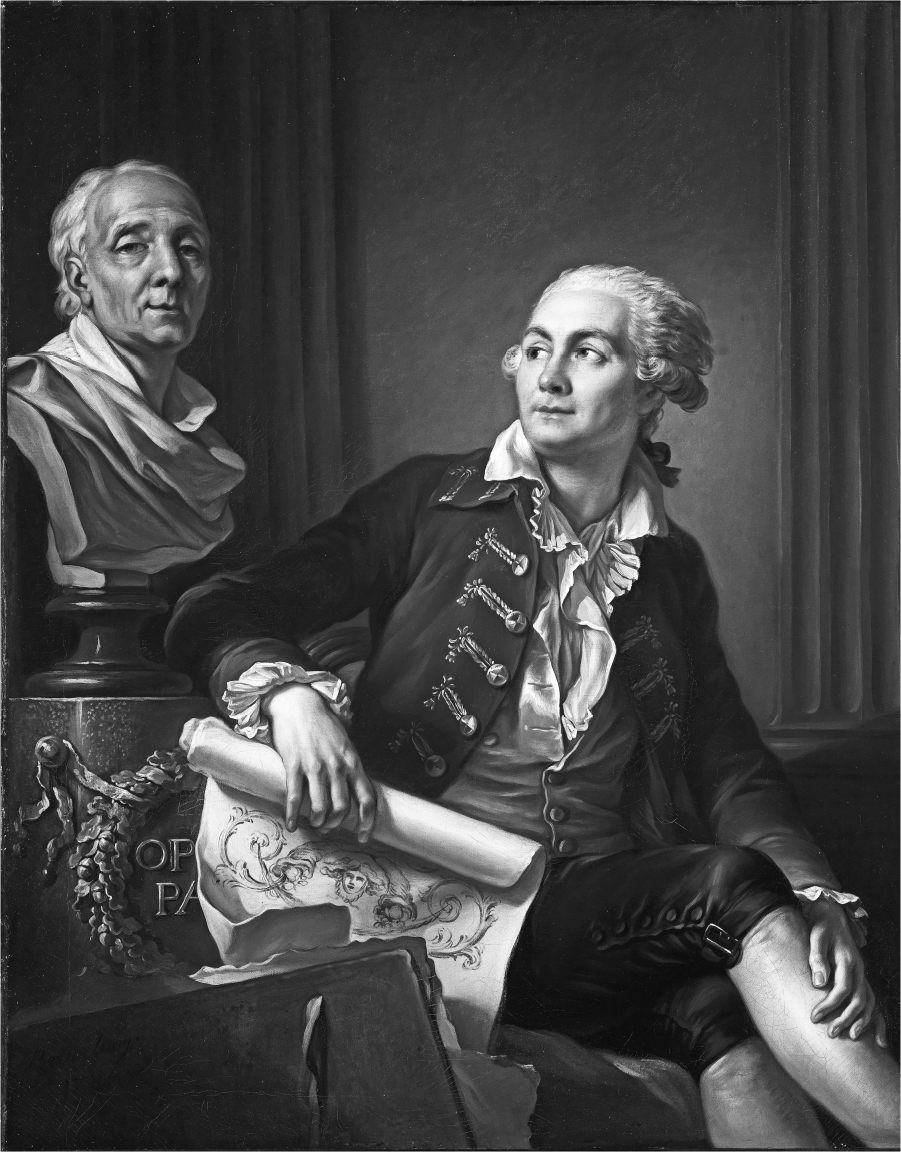

PORTRAIT OF A MAN WITH A BUST OF DENIS DIDEROT, PAINTING BY JEAN-SIMON BERTHéLEMY

Why Revolutionaries would consider the most progressive thinker of the Enlightenment at odds with their liberal values may not seem immediately obvious to us.40 And yet the politically astute leaders of the Revolution realized that there was no better way of dooming the movement than by letting it be contaminated by the atheism that Diderot represented. To do so would deprive the French citizenry not only of a God, but the comforting prospect of some form of afterlife. Bearing this in mind, most Revolutionary era leaders, regardless of their own beliefs, turned away from godlessness while simultaneously barring Diderot from their pantheon of intellectual heroes. Maximilien Robespierre, who was both a deist and a disciple of Rousseau, articulated Diderot’s sins far more succinctly. Since, from his point of view, the Revolution required a Supreme Being both to guarantee transcendence for its citizens and to justify the terror needed to purify the body politic, Diderot and the Encyclopedists were necessarily de facto counterrevolutionaries: they were corrupt, immoral, and contaminated as much by their ideas as by their proximity to the aristocracy.41

Diderot’s reputation did not fare much better after the Revolution turned on Robespierre in 1794. A year after the Jacobin politician was guillotined on the place de la Révolution, a former philosophe and acquaintance of Diderot’s named Jean-François La Harpe published a well-received book that held the departed writer responsible for the worst crimes of the Terror. This was, of course, terribly ironic. Having been castigated for his supposed royalist and aristocratic tendencies by Robespierre only months before, Diderot was now being associated with the execution of 17,000 French citizens, including hundreds of priests and nuns. That Diderot had somehow helped precipitate these heinous acts was seemingly confirmed two years later when his poem “Les éleuthéromanes” (“The Maniacs for Liberty”) appeared in print for the first time. Within this ceremonious Pindaric ode was a verse that soon became synonymous with the writer’s supposedly murderous politics: “And with the guts of the last priest let us wring the neck of the last king.”

Diderot had composed “Les éleuthéromanes” as flippant entertainment for a small audience, and had never circulated the poem before the Revolution.42 Yet its appearance in two major journals in 1796 — the same year The Nun and Jacques the Fatalist were published — cemented his reputation as the most godless and extreme of the philosophes.43 This turned out to be quite a dubious accomplishment: Diderot had not only been crowned the “Prince of the Atheists,” but was now being seen as a bloodthirsty ideologue hell-bent on the destruction of “all virtues and their principles.”44

Over the course of the next 130 years, the avant-garde and France’s traditionalists tussled over Diderot’s reputation. For the first eighty or so years after his death, conservative writers, monarchists, and the clergy had the upper hand in this quarrel. During the decades that France lurched from the Directory to Napoleon’s empire, back to monarchy, to constitutional monarchy, to republic, and then from yet another empire to yet another republic, traditionalists effectively portrayed Diderot as a godless radical, a sex fiend, a peddler of smut, and one of the causes of the nineteenth century’s unbridled secularism, individualism, and moral decline.

Diderot’s rehabilitation with the general population began in earnest in the final quarter of the nineteenth century when the Third Republic’s radicals, Freemasons, positivists, and scientists began publicly correcting so-called misconceptions regarding the writer’s career. This was an audacious effort. In lieu of shying away from the writer’s atheism and materialism, liberally minded thinkers now praised Diderot as something of a persecuted Galileo who had had the courage to storm the “intellectual Bastille” that had propped up the Church and the ancien régime. In stark contrast to the unsavory image of the writer that the right had been describing, his apologists now cast him as positivism’s predecessor: a torchbearer who had had the courage to lead his country away from the haven of piety and “to reorganize the world without God or a king.”45

DIDEROT AND HIS THIRTEEN MISTRESSES, FRONTISPIECE FROM A PUBLISHED SCREED AGAINST DIDEROT, 1884

By July 1884, exactly a century after Diderot had reached for his final piece of stewed fruit on the rue de Richelieu, posterity had seemingly understood the writer. Celebrations in his honor took place in various cities across France, including Langres, Moulins, and Nîmes. His adopted city of Paris, which had already named one of Haussmann’s new avenues the “boulevard Diderot” in 1879, organized several events as well.46

THE SALLE DES FêTES AT THE TROCADÉRO PALACE, PARIS, WHERE CEREMONIES HONORED DIDEROT IN 1884

On Sunday, July 27, 1884, over three thousand people squeezed into the Trocadéro Palace’s Salle des Fêtes to listen to the philosopher and positivist Pierre Laffitte describe Diderot as one of the most wide-ranging “geniuses to have ever lived.”47 Later that same day, a thousand Freemasons and their families also gathered in the eastern portion of the capital for a banquet and ball to honor the godless philosophe. These ceremonies were a prelude to a more concrete tribute to Diderot on the following Wednesday: the inauguration of a statue at the intersection of the relatively new boulevard Saint-Germain and the rue de Rennes, only steps away from where the philosophe had spent thirty years of his life on the rue Taranne.48

GAUTHERIN’S STATUE OF DIDEROT ON THE BOULEVARD SAINT-GERMAIN IN PARIS

The artwork’s creator, Jean Gautherin, portrayed the writer as a brawny, combative, and long-boned man whose muscles bulge from his waistcoat and stockings. Diderot leans forward, plume in hand, head cocked probingly to the left, a vision of the freethinker and writer who dared defy censors, Versailles, and the Church.49 In the days after the dedication of this statue, one liberal journalist mused,

Of all the eighteenth-century philosophes, the most in vogue is now Diderot, without a doubt. Rousseau is falling, because he is sentimental and a deist. Even Voltaire has fallen because, despite his war against l’infâme, he was sometimes wrong to believe in God…Voltaire was a man who dared rip out the guts of the last priest, but he would not have used them to strangle the last king. Only Diderot, after a bit of hesitation, and a few distractions without consequence, showed himself to be as much a democrat as he was an atheist.50

Catholic newspapermen did not miss out on the significance of this politically motivated public artwork either. It was hard to miss that this latest example of republican statuemania had been positioned in such a way that Diderot appeared to be looking out distrustfully at the spire of the neighboring Church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, like a “secular sentinel.”51

Neither Diderot’s detractors nor his disciples were wrong to emphasize the author’s career-long campaign against God. And yet, today, incredulity is far from the most compelling aspect of his writing. What really distinguishes him from his peers is what he accomplished after doing away with the deity. Although Diderot is undoubtedly the steward of the age of the Encyclopédie, he is also, paradoxically, the only major thinker of his generation who questioned the rational perspective that is at the heart of the Enlightenment project.

Writing in an era of powerful systems and systemization, Diderot’s private thinking opened philosophy up to the irrational, the marginal, the monstrous, the sexually deviant, and other nonconformist points of view.52 His most important legacy is arguably this cacophony of individual voices and ideas.53 Readers today continue to be amazed by his willingness to give a platform to the unthinkable and the uncomfortable, and to question all received authorities and standard practices — be they religious, political, or societal. As philosophers go, Diderot is neither a Socrates nor a Descartes, nor did he ever claim to be.54 Yet his joyful and dogged quest for truth makes him the most compelling eighteenth-century advocate of the art of thinking freely.