Chapter 4

Railroads and mass distribution, 1850 –1880

The decades after 1850, and especially following the Civil War (1861–65), ushered in a period of unprecedented economic innovation, productivity, and societal transformation in the United States with the advent of new sources of energy, new methods of communication, and new modes of transportation. This period of growth continued well into the twentieth century, completely revolutionizing the business landscape in the United States.

In energy, one significant change was the growing use of coal as a source of power. Anthracite coal, a harder, cleaner-burning variety than the more common bituminous coal, was prized for use in factories and homes. Bituminous coal was used in the production of coke, a porous fuel used in steel blast furnaces. By mid-century, Pittsburgh emerged as the central market for both types of coal.

In communication, the invention of the telegraph in the 1840s made the delivery of messages and news, even across continents, nearly instantaneous. In 1844, Samuel Morse sent the now-famous first telegraph message, “What hath God wrought,” from the Capitol Building in Washington, DC, to Baltimore. By 1851, there were more than fifty telegraph companies operating in the United States. Just ten years later, in 1860, more than 2,000 miles of telegraph lines connected cities across much of theUnited States.

Innovations in both energy and communication found application in the most important industry of the period—the railroad. Increases in coal production accelerated the construction of railway lines, while telegraphs improved the ease and efficiency of communication, making it possible to manage large businesses over vast spaces.

Railroads

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, many entrepreneurs and inventors experimented with new methods of transportation. The most transformative was the steam-powered locomotive. While the first locomotives were of British design, American engineers quickly adapted the technology to the American terrain and geography.

In the United States, the first railways were built in the 1820s. State charters authorized entrepreneurs to undertake rail transportation projects, including the 1826 Granite Railway, a three-mile wooden railway using horses to haul granite to a nearby river to supply the construction of the Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown, Massachusetts. Entrepreneurs in New York, Maryland, and South Carolina soon constructed similar short railways.

Railroads became an essential way for many American cities to gain easier access to agricultural output and manufactured goods. One of the first cities to capitalize on this technology was Baltimore. Maryland-born businessmen Philip E. Thomas and George Brown wanted to bring a railway to Baltimore to help the city compete with New York after the building of the Erie Canal. In 1830, they founded the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, taking passengers in cars pulled along by horses. Steam locomotives soon replaced horses. Peter Cooper—builder of the first American steam locomotive, named the “Tom Thumb”—challenged a horse-drawn car to a race. The horse won, but Cooper nevertheless convinced the owners of the railroad of the potential of his new technology. The railroad line eventually became one of the nation’s largest, reaching the Ohio River in 1852 and ultimately opening stations in twelve states and the District of Columbia.

Initially, there were numerous small railroads built to connect major cities to outlying towns—Boston to Lowell, Newburyport, and Providence; Camden to Amboy; Philadelphia to Reading and Baltimore. In the 1840s, more reliable construction methods began to make railroad technologies better and more uniform, allowing railways to supplant canals and turnpikes for transporting passengers and freight.

Rail transport had many advantages over canals and steamboats. Trains could move goods in all seasons and all weather, and, above all, they traveled comparatively fast. The trip from New York to Chicago, which would have taken at least three weeks in 1840, took only three days by 1857; a trip from Boston to New York or New York to Washington took only a day.

Cornelius Vanderbilt pioneered in railroad building and consolidation. Vanderbilt was born into a poor family on Staten Island, New York, just a few years after the ratification of the Constitution, and lived through the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. At age eleven, he was helping with his father’s ferry business. By age twenty, he had bought his own boat and was competing to establish routes along the East Coast. He was a tenacious competitor and frequently undercut established shipping companies by offering lower prices until they folded—and then he would often raise rates. He was bold enough to challenge a steamboat monopoly that had been granted by New York State to Robert Livingston and Robert Fulton, two early and prominent figures in the industry. Vanderbilt was able to break their monopoly and then expanded his ferry services, including the operation of a steamboat from New Jersey to New York. Succeeding in his ferry services, including ownership of the Staten Island Ferry, Vanderbilt also entered the business of oceangoing steamboat services following the discovery of gold in California. Then, he turned his attention to the most exciting technology of his generation: the railroad.

During the 1850s, Vanderbilt bought stock in several railways, including the Erie Railway, the Central Railroad, the Hartford and New Haven, and the New York and Harlem. By 1864, Vanderbilt gained control of the Hudson River Railroad and, in 1867, the New York Central Railroad. In 1869, he began construction of Grand Central Depot as the terminal of his New York Central Railroad, which connected New York City with Boston, Chicago, and St. Louis. (It became Grand Central Terminal in 1913 and now is adorned by an 8 1/2-foot statue of the “Commodore,” as he was known.) When he died, Vanderbilt was said to control more than a tenth of the entire capital of the United States.

Another pioneer was the industrialist and civil engineer John Edgar Thomson of the Pennsylvania Railroad. In terms of sheer size, the Pennsylvania Railroad, established in 1846, became the most extensive railroad in the world. Thomson was chief engineer and president of the Pennsylvania Railroad and built rails across the Allegheny Mountains to connect Harrisburg and Pittsburgh. Thomson also oversaw the financial and organizational challenges of growing the railroad west to Ohio and east to Philadelphia. To do this, Thomson introduced new technology, turning from wood to coal for fuel and from iron to steel for rails and cars. Like Vanderbilt, Thomson acquired many other railroads, canals, and shipping companies. Before the end of the century, one could travel to a wide range of US cities on the Pennsylvania Railroad, including Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Toledo, St. Louis, and Washington.

The government facilitated the growth of the railroads. From 1855 to 1871, a US government land grant system allotted 129 million acres to railroad companies. This allowed the opening of railways from Chicago and Omaha all the way to San Francisco. Starting around the middle of the nineteenth century, many Americans and immigrants pushed west on railways as the discovery of mineral ores (or even just the rumors of such discoveries) attracted miners and opportunists. So-called boomtowns sprang up around mines all over the West—capitalizing on the need for supplies, wagons, and mining equipment—and saw significant increases in population in just a few years. After James Marshall discovered gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, “forty-niners” rushed to California from all parts of the United States and abroad. San Francisco, which had only 1,000 residents in 1848, grew to 36,000 by 1852. Chinese immigrants, in particular, flocked to California goldfields in the thousands.

By the end of the 1860s, railroads traversed the nation. On May 10, 1869, Central Pacific Railroad Company president Leland Stanford drove the ceremonial golden spike that linked the Union Pacific and Central Pacific to form the first transcontinental railroad. Stanford embodied the combination of money, government, and industry that had together achieved this feat. Along with his brothers, Stanford had gone to California during the Gold Rush, making money as a partner in mining companies and as a storekeeper selling tools and supplies for miners. He became involved in California politics, helping to establish the Republican Party and, in 1861, was elected governor of the state. Stanford’s platform for the gubernatorial nomination included an endorsement of the effort to build the transcontinental railroad, and he was named the president of the Central Pacific railroad during his candidacy. His legislative record was decidedly friendly to railroads, and despite some opposition, he pressed for subsidies and substantial loans to the Central Pacific in its bid to expand and connect with an eastern line. Like Vanderbilt, Stanford invested in steamships, and the Central Pacific Company controlled river traffic on the Colorado and profited from oceangoing trade into and out of San Francisco.

Railroad management

Given their unprecedented scope and scale, railroads brought changes to the structure and organization of business. One was the promotion of a growing profession—the salaried manager. Once railroads spanned distances of a hundred miles or more, managing them required new modes of communication. Schedules, budgets, and procedures could no longer be worked out by colleagues in a single office. Failure to coordinate the movement of trains along a single track led to costly and sometimes fatal collisions. Railroad owners began to respond to these conditions with new organizational structures, and the railroads also became one of the largest and earliest users of the telegraph to coordinate complex schedules. Indeed, as time went on, telegraph lines were increasingly laid or relocated along railroad tracks to assist with maintenance—a case of transportation and communication flourishing together.

Unlike the manufacturing firms of the early nineteenth century, the railroads employed thousands of people. With the growth of railroads came the need for managers to hire and train new personnel (most coming, at least in the early decades, from an agricultural background), to draft new rules for operation, to negotiate issues of finance and distribution, and to satisfy regulatory policies. Railroad companies were organized hierarchically, with managers working in separate departments to handle different administrative functions: president, treasurer, general superintendent, division superintendent, secretary, land agent, auditor, foreman, car inspector, master of engine repairs, and so on.

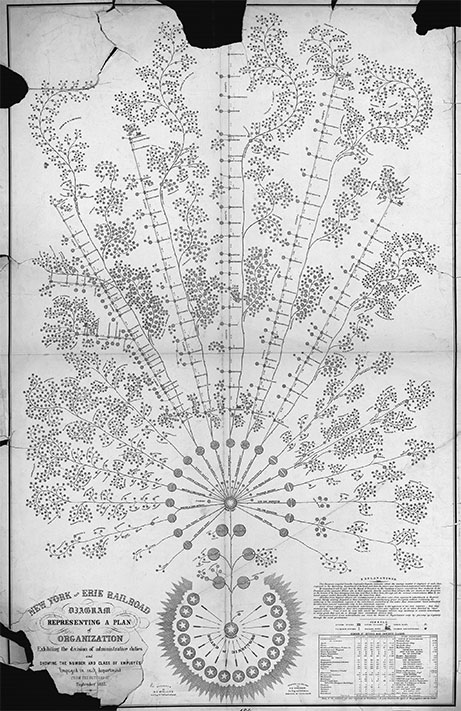

In 1855, Daniel McCallum, general superintendent of the New York and Erie Railroad, created a detailed organizational chart to show lines of authority within a single company, in a design reminiscent of the branches of a tree. A year later, in his report to the board, he articulated six principles of general administration, including “a proper division of responsibilities” and “the adoption of a system, as a whole, which will not only enable the general superintendent to detect errors immediately, but will also point out the delinquent.” McCallum’s report introduced ideas about channels of authority and communication that were critical to the growth of railroads and, later, of other large American businesses. Many of the large railroads subsequently adopted structures and procedures similar to those McCallum had pioneered at the New York and Erie.

In overseeing the operations of the railroad, managers encountered periods of labor unrest. When economic conditions worsened in the 1870s, especially with the Panic of 1873, some lines fell into bankruptcy and failed to pay their workers. The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, which lasted for more than a month, occurred after the Baltimore and Ohio reduced wages for the third time that year. Unrest spread to workers on other lines throughout the country.

The strike was part of a new phase in the development of organized labor in the United States at that time. The Knights of Labor, founded in 1869, espoused a broad platform advocating for the rights of all workers, including farmers. Membership grew rapidly in the 1870s, and the organization reached a peak membership of 700,000 in the mid-1880s. Around this time, however, a new labor organization founded by Samuel Gompers emerged, the American Federation of Labor, which was an alliance of craft unions. Gompers and the American Federation of Labor prioritized economic concerns, specifically working toward the “bread-and-butter” issues of wages, benefits, hours, and working conditions and advocating for the use of strikes and boycotts as a bargaining tool. The American Federation of Labor came to embody the model for unionism in the United States.

3. Daniel McCallum and George Holt Henshaw, “New York and Erie Railroad diagram representing a plan of organization,” 1855. A tree-like organizational chart of the railroad shows the towns and stations covered in the plan’s spreading branches, and the managerial and executive positions are shown in the circular roots below.

Corporations

Along with management, railroads brought sweeping changes to the financial industry and spurred the creation of global capital markets. The largest railroads had initial capitalizations from $17 million to $35 million, compared to textile mills and metalworking factories that were rarely capitalized at over $1 million. Because railroads were so expensive to build, they could not be financed with local capital alone and thus provided ideal investment opportunities for Europeans with surplus capital looking to invest in the growing industries of North America.

To raise money more effectively, railroad leaders formed corporations, an organizational form that became increasingly common in the United States in the nineteenth century. Initial investors living in the region of a railroad frequently bought stock in the company, while European investors typically preferred bonds. Unexpected costs incurred by railroad companies often meant that the first sale of mortgage bonds was usually followed by a second and a third. In this way, railroads became a boon to financial markets. The railroads, too, created an opportunity for analysts like Henry Varnum Poor, who developed Poor’s Manual of Railroad Securities, one of the first industrial journals, to inform those wishing to invest.

Railroad bonds and, to a lesser extent, stocks dominated Wall Street trading from the end of the Civil War to the beginning of the twentieth century. Those with money to risk often reaped great rewards—speculators, among them Daniel Drew, Jay Gould, and Jay Cooke, all made fortunes from their investments in railroads and even gained control of some railway lines. Trade and speculation surrounding these stocks and bonds contributed to the growth of the New York Stock Exchange (which was founded in 1817, but had not yet become dominant among other exchanges that existed at the time, including in Boston, Philadelphia, New Orleans, and Cincinnati).

However, railroad speculation could also have negative consequences for the national economy. Railroad speculation, corruption, and the sale of “watered stock,” or shares issued at a greater value than justified by a company’s assets, contributed to the Panic of 1873, a financial crisis in the United States and Europe that lasted several years.

Mass distribution

Railroads had a significant impact not just on management and finance but also on distribution. Commerce that had previously relied on rivers running from north to south now traveled on rail from east to west. The railroads enabled large-scale settlement in the Midwest, and they helped to create the beginnings of a national market, which made a difference in many areas of commerce, including in the quality and availability of food. Whereas Americans living in rural areas previously had to depend on homegrown food, grocers could now expect regular shipments of flour, spices, and many other foods from distant wholesalers.

Chain stores were one new form of organization to emerge during this period. Making use of the railroad, the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, an early chain store, began operation in 1859. The first location—a small store in New York City—expanded to sixteen cities by the time its founder retired in 1878. By 1900, the chain had grown to 200 stores in twenty-eight states. In 1879, F. W. Woolworth opened the first of its five-and-ten-cent discount stores in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. By 1904, there were 120 stores operating in twenty-one states.

Mail-order stores, too, got their start at this time, enabled by advances in the postal system and the expansion of the rail network, which increased the speed of delivery while reducing the cost of postage. For example, in 1847, railroads carried just 10 percent of mail and postage cost five cents an ounce within a range of 300 miles. By 1857, railroads carried roughly a third of all mail, and postage rates had dropped to three cents an ounce for a range of 3,000 miles.

Aaron Montgomery Ward built the first large catalog sales business beginning in 1872, when he introduced a single-page catalog. By 1887, the catalog had grown to more than 500 pages and advertised some 24,000 products. By the turn of the century, the catalog was nearly 1,000 pages in length, and annual sales reached $7 million. Competition soon came from Richard Sears, who began selling watches by mail in 1886, with partner Alvah Roebuck. In the recession of 1893, Aaron Nusbaum and Julius Rosenwald became partners of Sears, Roebuck and Company, and Rosenwald played a major role in expanding the line of goods and managing the mail-order operations. It took Sears only a few years to overtake Montgomery Ward in terms of profits—through analytical management, savvy advertising, and low prices. By 1900, there were more than 1,200 mail-order companies in the United States.

The advent of Parcel Post for package delivery in 1913 again revolutionized the marketplace, especially in rural areas, where it vastly extended coverage. The Post Office handled more than 4 million packages on the first day of this service. It was a boon to farmers, especially—providing access to a much wider variety of goods at competitive prices—and allowed established businesses like Sears to expand their offerings dramatically.

A third type of innovative channel of distribution appeared in these decades: the department store. In 1858, Rowland Hussey Macy opened R. H. Macy & Co. in New York City on Sixth Avenue between 13th and 14th Streets. In 1902, the store moved to its current location in Herald Square. Philadelphia’s Wanamaker’s department store similarly had its start in the mid-nineteenth century. In 1875, John Wanamaker purchased a former Pennsylvania Railroad station to use as a massive retail location. These ornate department stores offered new and innovative sales policies. Macy’s, for instance, created a one-price policy to put an end to haggling. Wanamaker’s provided a money-back guarantee.

Department stores also sprang up farther west. In the 1850s, twenty-one-year-old Marshall Field moved from Massachusetts to Chicago and began working in a dry goods store. He later traversed the countryside as a traveling salesman, one of a swarm of so-called drummers who took sample cases from large wholesale houses to visit county stores throughout the United States. With the increasing number of such salesmen, rural merchants no longer had to make annual trips to large cities to purchase their inventory. In 1865, Field entered into a partnership with Potter Palmer and Levi Leiter to establish a new emporium, known as Field, Palmer, Leiter & Company. In 1879, the retail business moved to a new six-story building in downtown Chicago designed in French Second Empire style, with a mansard roof and sizeable central skylight. By 1881, Potter had withdrawn from the business and Field bought out Leiter’s shares, renaming the company Marshall Field & Company. Around this time, the store had 34 departments, including dress goods, notions, and gloves. It would have more than 100 departments by the turn of the century. In the 1880s, the store introduced a bargain basement, which proved so popular that it accounted for nearly one-third of sales. Field and one of his top executives, Harry Gordon Selfridge, tried to make shoppers feel welcome in the store by having clerks be courteous and greet frequent customers by name. (Selfridge later developed these and other qualities in his London-based department store.)

In addition to commercial products, the railroads also enabled the secure transport of heavy agricultural machinery and machine tools. The McCormick Harvesting Machine Company benefitted greatly from the railroad, especially after 1890, when many local lines had been developed in the Midwest and West. “It is perhaps needless to say that as soon as a railway penetrated a new district, one of the first passengers to alight at a hitherto isolated community was a McCormick representative looking for a dealer,” the company reported proudly. By linking entrepreneurial farmers with innovative manufacturers, the railroad transformed the prairies into farmland.

4. Lydia Pinkham, of Lynn, Massachusetts, created popular herbal tonics and vegetable compounds, often containing alcohol, for women. Along with other patent medicine makers, Pinkham was a brilliant promoter of her products, which featured ornate labels.

The railroads, finally, also carried businesspeople and speculators working on a smaller scale, including patent medicine canvassers. Patent medicines, though seldom actually patented, were potions marketed to cure a variety of ailments. Many were some mixture of vegetable compounds and alcohol. Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, once a home herbal remedy, became wildly popular in the 1870s. In advertisements, the compound was said to be “a positive cure for all the painful complaints and weaknesses so common to our best female population.” Patent medicines were also marketed through traveling medicine shows, which solicited testimonials and displayed colorful posters with exaggerated claims about products. These shows, including others like the popular Kickapoo Indian Medicine show, were forerunners of the modern advertising industry.

When the thirteen original states became one republic, they adopted the motto “E Pluribus Unum”: from many, one. The railroads and telegraph made this motto real in a new, unforeseeable way—allowing the nation to become increasingly integrated into a single large marketplace even, ironically, as the country itself continued to expand geographically. These advances in technology were especially important for the growth of American business, as both railroads and telegraph enabled the founding, and management, of the large industrial concerns that came to dominate the economy over the next half century and more.