Reduces water loss

Reduces water loss

Suppresses weeds

Suppresses weeds

Insulates against hot and cold

Insulates against hot and cold

Mulching has many benefits, not the least of which, as far as I’m concerned, is that you can walk around in your garden on rainy days and not have 3 inches of sticky mud on the soles of your shoes when you come back inside. I choose to ignore the experts’ warnings to stay completely out of the garden on wet days. I am careful not to touch anything, mindful that I might be transmitting some harmful bacteria or virus to the plants. And I try to stay in the middle of my mulched path so I don’t compact the soil near my plants. But it seems to be a compulsive ritual with me to go into my garden at least once a day. I need to squat down next to a row and gently (sometimes not so gently) try to coax young seedlings into growing faster, bigger, or greener. Not a scientific argument for mulching, I know, but certainly an emotional one.

For mulching’s technical benefits, I turned to Dr. Donald Rakow, Professor of Landscape Horticulture at Cornell University. According to Dr. Rakow, mulch’s three major benefits are reducing water loss from the soil, suppressing the growth of weeds, and protecting the soil from temperature extremes.

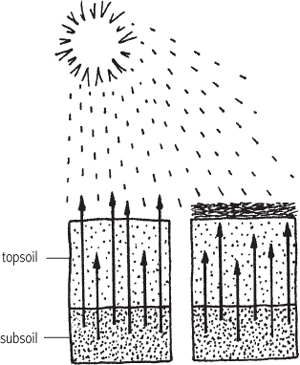

Mulch’s ability to conserve soil moisture has long been documented. While authorities and test results differ, it is clear that mulch reduces moisture evaporation from soil by anywhere from 10 to 50 percent. Mulch’s water-conserving value can’t be overemphasized, especially during times of water restrictions, shortages, and drought conditions.

Mulch keeps soil from drying out partly because it prevents dew and water, drawn up from the subsoil, from escaping. Contrary to what many believe, dew is not only water condensation from the atmosphere; it is also moisture condensation from air pockets in the soil. As far as plant growth is concerned, most dew is completely wasted unless there is something on the surface to catch it and prevent it from evaporating.

Some impervious mulches, like black plastic or old boards, may catch more dew because they don’t allow air to pass through. The downside is that they also don’t let water or air in. That’s something to keep in mind when selecting a type of mulch. More on that later.

Mulch keeps soil from drying out by inhibiting evaporation of dew and moisture that is drawn up from the subsoil by capillary action.

Mulching can practically eliminate the need for weeding and cultivating. Imagine how much extra time that will leave you for picking strawberries, lying in the hammock, or visiting other gardeners!

There are a few catches, however. First, the mulch itself must be weed free. Many a gardener’s best mulching intentions have gone astray with one application of weed-strewn hay or manure. Rather than controlling weeds, they ended up introducing a whole new pesky weed crop.

Second, mulch must be deep enough to prevent existing weed seeds from taking root. Weed seedlings need light to grow. Weeds sprouting under a dark blanket of mulch wither away without light. If mulch is applied too thinly, weeds may still poke through. So when you mulch, be as persistent as a weed and cover all open areas.

Finally, mulches won’t smother all weeds. Some particularly tough weeds have the fortitude to push through just about any barrier. In a well-mulched bed, though, these intruders should be easy to spot and even more easily plucked.

Mulch’s ability to regulate soil temperature is probably one of the benefits most often overlooked, especially by first-time gardeners. Many of us are so concerned with aboveground temperatures that we don’t spend much time pondering what’s happening underground.

Simply stated, mulch is insulation. It keeps the soil around your plants’ roots cooler during hot days and warmer during cool nights.

In winter, mulch works to prevent soil from alternately freezing and thawing, which leads to soil heaving and root damage. Now this doesn’t mean the soil won’t freeze; it just won’t happen overnight. Rapid freeze-thaw changes not only threaten aboveground growth, they also may send tender plant roots into shock. That’s why it’s best to apply winter mulches in the fall, after a good frost when the plants are dormant. Come spring’s warm weather, be sure to remove the mulch when plants start sprouting new growth.

On the other hand, mulches are useful for controlling soil temperatures in summer. These are frequently referred to as “growing” or “cultural” mulches. Applied in the spring after the soil starts to warm up, they stay in place for the majority of the growing season.

Extremely high soil temperatures can inhibit root growth and damage some shallow-rooted plants. During the long, hot days of summer, a mulch can reduce soil temperature by as much as 10°F.

Some plants, though, thrive in heat. Besides organic mulches, there are special synthetic mulches for them. Tomatoes, eggplants, and peppers appreciate high temperatures. Black or red plastic around tomatoes has been shown to increase fruit yields.

Mulch is insulation. It keeps soil around plant roots cooler during hot days and warmer during cool nights.

You can remove some or all of an organic mulch at the end of the season. Most types are usually incorporated right into the soil — which leads us to some of the other benefits of mulching.

Mulching prevents soil compaction and crusting by absorbing the impact of falling raindrops. Water penetrates through loose, granulated soil but runs off hard, compacted earth. Mulch controls wind and water erosion by slowing water runoff. Mulch helps to hold soil in place — a benefit for the ornamental perennial bed as well as the steep slope. This is why you see newly grassed banks along highways covered with mulch. It keeps the dust down, too.

Organic mulch can be a soil conditioner. Some soil that might normally break up into chunks when tilled or cultivated will crumble into fine granules after even just a few weeks under a biodegrading mulch.

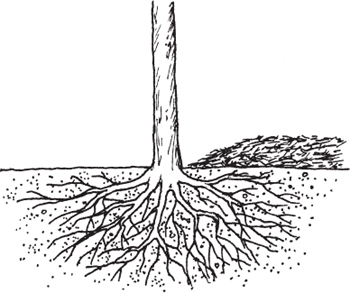

Many organic mulches, like shredded leaves and bark chips, add organic material to soil as they decompose. This leads to all sorts of great things. Enhanced soil structure, for example, improves aeration, water percolation, and nutrient movement throughout the soil.

Mulching encourages earthworms, which further aerate the soil and release nutrients in the form of “castings.” Earthworms should be considered prominent citizens in any garden! They are particularly important in perennial beds and rarely plowed or tilled garden plots. Mulching keeps your soil friable and hospitable to earthworms, who’ll gladly do much of the underground work for you.

Mulch stimulates increased microbial activity in the soil. Certain bacteria are every bit as important as worms. Microbes break down organic matter rapidly, making plant nutrients available to roots sooner. This means, as Ruth Stout suggests, that your garden is operating very much like a compost heap.

Mulched plants are less diseased and more uniform than those without mulch. One reason is that mulching prevents fruits, flowers, and other plant parts from being splashed by mud and water. Besides causing unsightly spots and rot, splashing can carry soilborne diseases. Mulch protects ripening vegetables, like tomatoes, melons, pumpkins, and squash, from direct contact with the soil. That means fewer “bad” spots, rotten places, and mold.

Although the jury is still out on whether mulches help control harmful soil nematodes or fungi, there is some evidence that a few light-reflective types, such as aluminum foil and polyethylene film, may reduce aphid and leaf miner populations and some diseases that they spread.

Basically, mulching helps reduce plant stress. Healthy, strong plants have the energy and resources to better protect themselves against insects and other pests.

Organic mulch can increase available potassium by allowing it to attach to the decaying mulch instead of to the soil particles. When fixed to the soil, a good deal of potassium isn’t accessible to a plant. Depending on their age, type, and duration of exposure, mulches can also contribute nitrogen, phosphorus, and several trace elements to the soil chemistry.

Mulches aren’t dependable as a primary plant food, though. Dr. Rakow suggests supplementing mulched areas with other fertilizer because mulch alone may not be enough. Herbaceous plantings may actually show signs of chlorosis without an additional feeding or two of fertilizer.

Using mulches for weed control helps reduce our dependence on chemical herbicides. The fewer chemicals we use, the lower the risk of groundwater contamination, general exposure to toxins, and accidental poisonings.

Mulching is an excellent way to reduce and recycle yard waste. Even if you live on a quarter acre of land and have a small garden, you generate tremendous amounts of waste in and around your home. Rather than burning leaves or carting cut grass off to a landfill, use them! Dead (not diseased or insect-infested) plants, leaves, grass clippings, old newspapers — just about anything is fair game for the mulch pile. Even larger woody materials can be converted into mulch with a portable chopper or shredder. But be sure not to add poison ivy, sumac, or oak to your mulch. And don’t reuse diseased or insect-infested materials; they’ll only spread the problem. Thoughtful recycling helps your plants and the environment at the same time.

While they don’t have the most scientific of reasons, many folks mulch just because they like the way it looks. Ask your friends why they mulch. I’ll bet they won’t say “to free up my soil potassium.” They will probably say mulching makes their gardens look a little better or neater. Or maybe they just like the color or texture a certain mulch lends to their landscape. Mulching an ornamental bed with shredded bark or hardwood gives it a professional touch.