4

A FEW DEFINITIONS

I find that many good gardeners — probably because they like to garden more than they like to study the technicalities of gardening — use gardening terms rather loosely. Ask 10 gardeners to define a word like mulch or compost and you will get the proverbial 10 different answers. Interestingly enough, in the particular case of these two words (compost and mulch), the varying descriptions are not only confusing, they frequently overlap and are sometimes reversed.

Here seems a good place to explain some terms already mentioned. These are not meant to be strict, inflexible definitions. In fact, you may disagree with them totally. They are offered simply as working definitions to describe what I mean when I use a particular word. Let’s start with compost.

Compost is organic matter undergoing or resulting from a heat-fermentation process. This heating, generated by intense bacterial activity, may develop temperatures as high as 150 or 160°F near the center of the compost pile. Heat is the factor distinguishing compost from mulch. In other words, if the material has not heated, it is not compost.

Humus is dark, rich, well-decomposed organic material. The end result of all composting (and mulching, eventually) is humus. When garden topsoil contains a generous amount of humus, the garden is probably fertile, productive, and full of plump worms. Rotting organic matter cannot be considered humus until you no longer can identify the original compost material. Humus is the ultimate and highly coveted byproduct of thoroughly decomposed mulch as well as compost.

Mulch can be any material applied to the soil surface to retain moisture, insulate and stabilize the soil, protect plants, and control weeds. A properly functioning mulch has two basic properties. Good mulch should be 1) light and open enough to permit the passage of water and air and 2) dense enough to inhibit or even choke weed growth.

Mulches can be divided into two fundamental categories:

1. Organic mulches are like unfinished, unheated compost. Any biodegradable material (anything that will rot) can be used as organic mulch. Organic mulches are preferred for the noncommercial home gardener. Vegetable matter is better than something like old cedar shingles, planks, or magazines and newspapers — although these do make effective mulches if you don’t mind seeing them in your garden. The most common organic mulches are shredded or chipped bark, leaves and leaf mold, hay, straw, grass clippings, and by-products like cocoa hulls, ground corncobs, and spent hops from breweries.

2. Inorganic mulches, sometimes called inert or artificial mulches, don’t begin as plant material. They can be substances that never rot, such as colored plastics, or they can be mineral products like crushed stone and gravel chips. Another example of inorganic mulch is geotextile landscape fabric, spun-bonded or woven from polypropylene or polyester, cut for and used as mulch.

Universities and the agricultural industry are continually researching the pros and cons of colored plastics on small fruit and vegetable crop production, so keep your eyes peeled for the most current information. In the meantime, I’ve included the latest on plastics, geotextiles, and more in chapter 5.

Here are a few other terms associated with mulching that are sometimes bandied about:

Summer mulches, or growing mulches, are applied in the spring after the soil starts to warm. Throughout the summer, they insulate the soil, inhibit weed growth, retain moisture, and control erosion. Both organic and artificial mulches fall into this category.

Winter mulches are used around woody plants and perennials to insulate against freeze-thaw damage to plants’ crowns and roots. Winter mulch is applied in late fall after the soil has cooled, preferably following a hard frost. The idea is to keep the soil temperature from jumping up and down and heaving plants out of the ground. Ordinarily, winter mulches are organic, but geotextiles may provide adequate winter protection.

Living mulches are low-growing, shallow-rooted, ever-spreading ground cover plants like vinca, myrtle, thyme, sweet woodruff, English ivy, and pachysandra. These mulch plants are attractive and commonly used in border flower beds, ornamental plantings, and rock gardens, but they can be effective in the food garden as well.

Permanent mulches are usually made up of nondisintegrating (not necessarily nonbiodegradable) materials. Permanent mulches like crushed stone, gravel, marble chips, and calcine clay particles are useful, particularly in perennial beds, around trees and shrubs, and on soil not likely to be tilled or cultivated.

Green manures (green-growing mulch) are basically cover crops like ryegrass, alfalfa, and buckwheat that meet the definition of mulch. They afford fine winter and erosion protection with the added advantage of attracting beneficial insects during the growing season. They can be tilled under as sheet compost or harvested and applied as mulch in another part of the garden. Cover crops are used mostly in vegetable gardens or small fruit plantings.

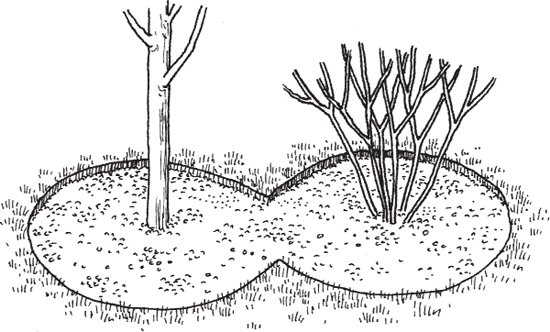

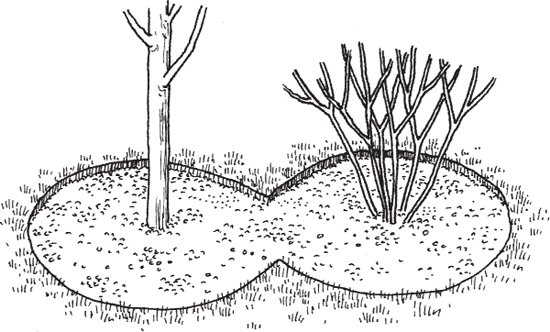

A permanent mulch of stone works well around trees and shrubs.

Sheet composting is when a layer of organic matter (alfalfa stalks or leaves, for example) is laid on the top of the growing surface and then worked into the earth by plow, rototiller, or spade. Once covered or partially covered with dirt, the organic matter decomposes very rapidly but without heat.

Homemade mulches usually consist of plant-based materials gleaned from household refuse, especially from the garden. They include dry coffee grounds, tea leaves, chopped paper, stringy pea pods, and wilted Swiss chard leaves. Vegetable leavings, if not tossed on the compost heap, are fine to throw directly on the garden. (No meat, bones, fat, or dairy products, though; these will attract critters.) If this somehow offends you or might upset a neighbor, discreetly tuck the vegetable discards under the mulch already there. Who’s to know? Neighborhood dogs, incidentally, are not attracted to coffee grounds, for example, if they are buried under so much mulch that no scent can escape. Homemade mulches are historically popular with vegetable gardeners. With the ease of chipper/shredders, many home gardeners are creating their own landscape mulches from pruned branches and fallen leaves.

Feeding mulches will rapidly add plant food to your soil. Rotted leaves, manures, and compost (compost can also be used as mulch) are the most obvious kinds of feeding mulches.

Seed-free mulches are just what the name implies: organic mulch that has not yet or never will go to seed. This can include hay that has not blossomed or is sterile. With a seed-free mulch, there is no danger of donating potential weeds to your garden.

I hope this chapter has cleared up a few things so that the rest of the book will make sense. Please refer back to it whenever necessary.

Organic or artificial material

Organic or artificial material Unheated, 2- to 4-inch blanketlike layers

Unheated, 2- to 4-inch blanketlike layers Use on top of soil to inhibit weeds, conserve moisture, control erosion, and stabilize soil temperature

Use on top of soil to inhibit weeds, conserve moisture, control erosion, and stabilize soil temperature Heat-fermented organic material

Heat-fermented organic material Large piles hot with microbial activity

Large piles hot with microbial activity Use mixed with topdressing or as soil amendment to provide food for microbes, worms, and plants

Use mixed with topdressing or as soil amendment to provide food for microbes, worms, and plants