Understanding why you mulch roses is half the battle toward doing it right:

To maintain an even temperature around the plants

To maintain an even temperature around the plants

To avoid repeated freezing and thawing

To avoid repeated freezing and thawing

Ornamental plants give beauty to our landscapes. They are the trees, shrubs, perennials, annuals, and bulbs cultivated for their visual appeal around our homes and businesses. Every year homeowners spend millions of dollars to add height, variety, texture, and color to their front and back yards. Mulching is a simple way to help protect and enhance that investment.

Mulching is an integral part of landscaping for several reasons. A richly textured, attractive mulch adds a professional touch to any ornamental bed. Plants can shine as stars while the earthy mulch provides a complementary background. Mulching an ornamental bed conserves water, controls weeds, mediates soil temperature, and stops erosion. Healthy ornamentals improve a property’s value. All this makes it easier for you to enjoy more of your time at home.

With high water costs and frequent drought conditions nationwide, mulching is sensible, cost effective, and environmentally sound. As interest and activity in home landscaping climbs, so does the demand for water to keep the plants alive. Without mulch a large portion of this water, some say as much as half, simply evaporates into thin air.

Plants suffer without enough water. A fluctuating water supply stresses them, making them vulnerable to insects and diseases. By conserving water and regulating soil temperature, mulch helps to keep your trees, shrubs, and perennial beds healthy and lush. Also, an organic mulch decays to feed your plants naturally, encouraging worms and microbes who’ll do the underground work for you.

As most landscape plantings are perennial in nature, you can use more permanent mulching techniques and materials. It’s worth the time and effort to lay down a landscape fabric and cover it with lava rocks if you won’t have to hassle with removing it in the fall.

Mulch for landscaping, be it for a single tree or a handsome mixed bed of perennials, shrubs, and annuals, should appeal to the eye. Decorative mulches include shredded barks, stones, wood chips, cocoa hulls, and licorice root. Ground covers such as perennial vinca and pachysandra can act as excellent living mulch, keeping weeds at bay and soil in place in difficult or large areas.

Geotextile fabric topped with shredded bark, natural or colored wood chips, or stone is a popular landscape mulch. Redwood chips over landscape fabric is a good way to add color.

The basics of mulching apply to ornamental use, just as they do for vegetable gardens. Choose your mulch thoughtfully. Before applying any mulch, water the ground well and remove all weeds. Fertilize your plants according to package directions. Apply mulch evenly as if it were a blanket, 2 to 4 inches deep, depending on your mulch and the soil conditions. Don’t place mulch against any living stems, trunks, or branches.

To refresh old mulch, give it a light raking to fluff it up, renew the color, and break through any crust. If that doesn’t do the trick, remove an inch or two of the organic mulch (wood chips, bark). Then top with new mulch, adding about as much as you removed. Keep mulch in the 2 to 4 inch range. With mulch, more is not always better. Overmulching can be fatal.

Probably the number one cause of death for newly planted trees and shrubs is the lack of adequate water. We already know that mulch can help solve that problem. Mulching around the tree base also reduces the incidence of mower blight, a.k.a. lawn mower damage, a leading cause of tree death. You know how it is. You’re cruising along on your riding mower and cut it just a bit too close to the honey locust tree. Off flies a chunk of bark. While one or two of these weekend collisions won’t usually knock a tree out, enough of these bumps and bruises will damage the cambium and the tree will die. Not only that, open wounds in the bark can expose a plant to a number of disease and insect problems.

A good covering of mulch, 3 to 4 inches deep, right after planting will go a long way toward protecting the base of your trees. Before mulching a new transplant, clear away weeds and grasses from the soil surrounding the trunk. A circle 3 to 5 feet wide is a good start. Water generously. Then mulch that cleared area to suppress weeds and grass and help you resist the urge to mow right up to the trunk.

For mulching under established trees, experts recommend clearing weeds and grasses to the tree’s drip line. That means beneath the tree’s canopy, the shady area under the tree. If that’s too over-whelming, clear as large an area as you can. Something is better than nothing.

Next, apply organic fertilizer as directed and water the area well. Top with 3 to 4 inches of organic mulch. And stand back!

A work-saving alternative when temperatures drop in the fall is to spread fresh wood chips out to the drip line. They’ll do double duty. The heat from their decay will kill grass under the tree canopy and they’ll be acting as mulch, too!

Organic mulches like wood chips, shredded bark or nuggets, cocoa hulls, pine needles, root mulch, leaf mold, and shredded leaves are all smart choices for mulching trees. They decompose, adding to the soil nutrients that are easily depleted by all the tree’s shallow feeder roots. Crushed stone, marble chips, and gravel are fine, but they won’t enrich the soil and may be less attractive. Be careful when applying any rock-type mulches around woody plants. Rock mulches can do serious damage to woody plants if they hit the base of the tree. Remember to keep all types of mulch at least 6 inches from the tree trunk.

To mulch shrubs, follow the basic mulching guidelines. Remove as many weeds and grass clumps as possible, especially in the shady area under the shrub’s branches. Apply fertilizer if needed and according to package directions. Water well. Then apply your mulch of choice in an even 2- to 4-inch blanket over the root area. Remember, an organic mulch such as leaf mold or shredded bark will feed your plants for many months to come. Avoid having mulch in direct contact with the shrub’s base and branches.

There seem to be two shrubs that give people fits when it comes to mulching: rhododendrons and roses. I can understand that roses cause problems because of their demand for winter protection, but I’m not sure why rhododendrons do. I guess it’s because we grow rhododendrons and azaleas for their spectacular bloom and when we don’t get one, we want to find something to blame. Often, we blame the mulch.

Unmulched or undermulched rhododendrons and azaleas may suffer from chlorosis, weak and underdeveloped leaves, or even death. These plants cannot tolerate hot, dry soil. Their shallow feeding roots are severely injured under these conditions, and the plant has trouble putting out healthy leaves, never mind spectacular blooms. Mulching can help cool the roots and hold the moisture.

In addition, as mostly evergreen plants that carry their leaves all winter, they continually lose water to the air. If soil moisture is inadequate, the plant will lose water faster than it can replace it. The end result will be brown, scorched foliage, which in extreme cases may just give up the ghost and drop off. By watering the ground well and mulching rhododendrons in the fall, you can ensure an ample moisture supply and insulate the soil from sudden temperature changes.

Rhododendrons and azaleas both prefer acidic soils, and your mulch selection can play a part. I suggest you choose one of the organic mulches, like shredded leaves or pine needles. A dry mulch of shredded leaves (especially oak leaves), spread 10 to 12 inches deep, can be laid down at planting (remember, these will decompose quickly to give you a 3- or 4-inch layer). A 2- or 3-inch layer of pine needles will also do the trick, as will wood chips or sawdust, if sufficiently weathered.

If you use one of these mulches, water your rhododendrons following a fertilizer schedule, and still have an unhealthy-looking plant, something else is going on. Maybe you have an insect or disease problem or grew the wrong variety for your area.

Decorative organic mulch on a flower bed has multiple benefits:

• It adds the finishing touch.

• It conserves water.

• It controls weeds.

• It moderates soil temperature.

• As it decays, it adds nutrients to the soil.

What more could you ask for? The organic mulch you apply this spring will turn to fertilizer for next spring’s growth. I like layering first with 2 inches of leaf mold and topping that with 2 inches of a dark, shredded bark mulch. A mulched, well-fed perennial bed only improves with age. And each year you need to add less mulch!

Mulching a new mixed bed of perennials and annuals is easy. Put in the plants. Water generously and fertilize as needed. Carefully shovel mulch around the new transplants, making sure not to allow mulch to rest against the stems or on the crowns. Mulch on crowns and against stems invites rot, disease, and insect damage. Spread the mulch until you get an even blanket of material about 3 to 4 inches deep.

If your plants are small, such as young annuals, 2 inches of mulch outside them is fine. If you’ve grouped annuals close together, don’t sprinkle mulch between the flowers. Just start mulching an inch or two outside the group.

Remember: One of your major interests is weed control. A deeper mulch layer is best where weeds might be tempted.

Keep a close eye on your mixed bed for a week or two. If your plants start to turn brown or look wilted, check to make sure mulch isn’t in direct contact. If it is, pull it away. It’s not that mulch is harmful; it’s just that placed too close to stem and leaves, it can stifle airflow, trap moisture, and become home to insects and diseases.

Mulching an established mixed perennial bed is best done in spring after the soil has warmed and while the plants are filling out and you can move easily through the garden. As perennials return year after year, most will show their heads proudly. Some, like the balloon flower and coreopsis, are slow to emerge, so walk (and mulch) carefully. Also watch for sprouting seeds; they may be more perennials you’ll want to move or cultivate in place.

If you’ve planted in clusters or groups, mulch outside the clusters and cultivate inside. You want your perennials to have as much room to fill in as possible. The ultimate goal is to have a perennial bed full of, well, blooming perennials! Every year your perennials should spread farther and wider so you’ll need less and less mulch.

Weed, water well, and fertilize as needed before mulching. If there’s mulch from last season, hoe to loosen it before topping off with a new batch.

If you just don’t get to mulching early on, anytime is better than no time. Just remember to weed and water well in preparation. Then allow the foliage to dry before shoveling on the mulch. Placing mulch among fully grown perennials takes patience and precision, so give yourself plenty of iced tea breaks. Better you take an occasional rest than end up crushing your favorite veronica underfoot.

Although it’s a chore, be sure to go around and move the mulch an inch or two away from the base of each perennial. Otherwise, mulch in their crowns and against stems is likely to cause rot. I have a small warren hoe (an unusually small-sized triangle) that enables me to get at the base of most plants while standing. To reach some, I have to balance between thorny roses and my favorite, fragile Japanese anemones while bending over to move mulch aside with my gloved hand. Ouch!

Generally, winter mulching isn’t necessary if you mulched in spring. For fall transplants (shrubs and perennials) and late-season divisions, though, a loose winter mulch of evergreen boughs, pine needles, or pine bark chips is excellent extra protection. The same is true for marginally hardy plants and temperamental shrubs. Use a light mulch that won’t mat down, resist water, or be too comfortable a home for rodents. Whole leaves, although handy, aren’t a good idea; they’ll clump, mat, keep water out, and suffocate anything below. Shredded leaves work well, though. Remember to remove the light mulch in spring when you see new sprouts. Keep some boughs on hand in case you need to cover plants quickly as protection from a late frost.

Rose mulching offers a shining example of the differences between summer and winter mulches. Summer mulching is done in the spring to control weeds and maintain soil moisture. Winter mulches, put down after the ground has started to cool in the fall, serve to protect the plant from temperature extremes and soil heaving.

Just about everyone who grows roses agrees that winter mulching is necessary to protect their plants. They don’t always agree on how to do it. There are probably almost as many methods and materials for winterizing roses as there are rose growers. Winter mulching is fairly simple if you remember why you are doing it. Most roses are amazingly hardy. Mulch isn’t meant to keep them from freezing: The goal is to maintain constant temperature and avoid freezing and thawing repeatedly.

Here are three methods for mulching roses in winter. Whichever system you select, water the soil well before covering your roses and remove the mulch in the spring before new growth begins. If the mulch is left on until the buds start swelling, it may put the new growth into shock when you uncover it.

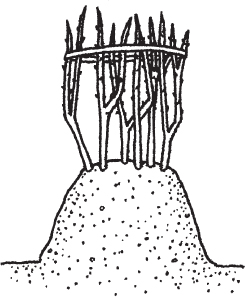

1. Mounded soil/mulch method. Probably the most accepted method for winter mulching roses is to take soil or organic mulch from elsewhere in the garden and make a mound of 10 to 12 inches around the base of the rose bush. Do this after the first hard frost. If it’s done too early, the roses may be fooled into a late growth spurt, which will delay dormancy and lead to more, not less, winter injury.

Come spring, gently hose away the soil and mulch, being careful not to break off any new sprouting branches.

For mulching roses in winter, mound soil/mulch at least 10 inches over each bush.

2. Rose cones/synthetic fiber blankets. Many rose growers combine the mounded soil/mulch method with other techniques. A wide variety of methods and products are available. In areas where the temperature stays well below freezing for most of the season, you will need to provide some additional protection. Some growers lean toward the Styrofoam rose cones that fit around the mounds; others prefer ground corncobs, sawdust, or chopped leaves. Synthetic fiber blankets are an attractive winter protection. Rose cones can overheat during those warm, sunny January thaws. To help keep your roses from “frying,” poke a ventilation hole in the top.

To keep your lightweight rose cones from winding up in your neighbor’s yard, weight down the cone with a brick.

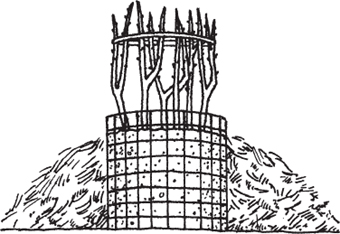

3. Wire cages. Wire cages filled with leaves or compost are often used instead of the Styrofoam cones. These cages needn’t be stuffed to the gills with leaves. This makes for poor air circulation and may lead to disease problems.

A cylinder of wire mesh holds mounded soil in place around canes.

Among true rosarians nothing can stir up such heated arguments as the subject of summer mulching. Some swear summer mulching is a must, while others swear at it. I personally feel it is a good practice.

Antimulchers feel that the threat of insects or diseases being introduced with a mulch outweighs the benefits. Usually these are dedicated growers who have time to pamper and hand-weed their rose beds weekly. I opt for the lower-maintenance, regular-observation method. For amateurs like me, mulching prevents damage to shallow roots during cultivation. I am careful not to mulch right up to the base of my bushes and mindful not to overwater the beds. Moist, damp conditions can foster many rose diseases.

Mulching hardy bulbs is not essential. But in a cold-winter area, the insulating value of a nice, thick organic mulch can’t be overlooked.

About 2 to 4 inches of shredded leaves, bark nuggets, wood chips, corncobs — just about any mulch that doesn’t pack down — is fine for bulbs. Apply mulch after the ground is frozen. Remove in the early spring at the first sign of green sprouts.