Tim Horton (Tim Hortons Doughnuts)

Tim Horton (Tim Hortons Doughnuts) CHAPTER 2

Bon Appétit: A Fascination with Food

Many great entrepreneurs got their start in Canada, and many of them were in the business of food production, distribution, and service. Here are a few who will be familiar to you:

Tim Horton (Tim Hortons Doughnuts)

Tim Horton (Tim Hortons Doughnuts)

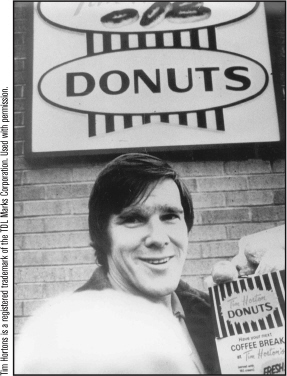

To many hockey fans, Tim Horton was a legendary National Hockey League defenceman whose name is etched onto the Stanley Cup four times as a member of the Toronto Maple Leafs. To those who couldn’t care less about hockey, he is a name on a sign and a synonym for a regular coffee and a Dutchie to go.

“Mr. Horton will be famous long after most Timbit dunkers have forgotten what he did for a living,” Globe and Mail reporter John Saunders once wrote.

In fact, Horton supported himself and his family by playing professional hockey in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, not by peddling Timbits, doughnuts, and coffee. During his hockey career, the Tim Hortons doughnut chain was merely a sideline, but one that would earn millions of dollars for others long after he was killed in a 1974 car accident.

Miles Gilbert “Tim” Horton was born in the northern Ontario mining community of Cochrane on January 12, 1930, about 18 months before Conn Smythe opened Maple Leaf Gardens. He was a quiet but muscular kid who played his early hockey in Copper Cliff near Sudbury before heading south to play for Toronto’s St. Michael’s Majors in 1947.

As a youngster, his dream was to be a fighter pilot. As a young hockey player, his focus changed to pro hockey and he developed into a tough but capable rushing defenceman. Shortly after joining the Majors, his penchant for penalties earned him the nickname “Tim the Terrible.”

After a promising junior career, Horton played for the Pittsburgh Hornets of the American Hockey League before he and his trademark Marine Corps brush cut joined Toronto as a regular rearguard in 1952.

Horton wore number 7 for the Leafs until the 1969–70 season when he was traded to the New York Rangers. In 1971–72 he joined the Pittsburgh Penguins before being acquired by Punch Imlach’s Buffalo Sabres in 1972. He was in his second season with Buffalo when he died.

Despite being shortsighted and nearly blind in his left eye (he was nicknamed Mr. Magoo and Clark Kent for the thick, dark-rimmed glasses he wore away from the rink), Horton was a rock-steady rearguard who left a legacy in the NHL. Playing for much of his career with fellow defensive stalwarts Allan Stanley, Bobby Baun, and Carl Brewer, Horton’s Leafs won the Stanley Cup in 1962, 1963, 1964, and 1967. He was voted to the NHL’s first all-star team three times and in 1977 was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame.

“He was one of those steady defencemen who never set many fires but was always around to put them out,” sports columnist Dick Beddoes once wrote about Horton, who was known for his powerful slapshot, extraordinary strength, and his love for doughnuts, fast cars, and booze. Teammates remember him as modestly confident about his abilities, approachable, generous, and considerate, although he had his share of off-ice temper tantrums.

The night of his death, the 44-year-old Horton was named third star after the Sabres fell 4–2 to the Leafs at Maple Leaf Gardens. He died at 4:30 a.m., when he was thrown from his high-performance Ford Pantera as it flipped several times after leaving the Queen Elizabeth Way in St. Catharines, Ontario. The car was a signing bonus when Horton inked his second contract with the Sabres.

During his NHL career, Horton logged 1,446 regular season games, scored 115 goals and 403 assists, and registered 1,611 minutes in penalties. Another impressive statistic was the success of his doughnut business, which in its first decade had grown from a single franchise to 35 outlets.

The business was launched in February 1964 when Horton and two partners formed Tim Donut Ltd., which licensed Horton’s name for use in their proposed chain of doughnut shops. Two months later, they opened the first Tim Hortons franchise on Ottawa Street in Hamilton, Ontario, where a dozen doughnuts cost 69 cents and a cup of coffee was a dime. As doughnuts filled with cream or jelly and coated with sugar and honey glaze flew off the shelves that spring, Horton was helping the Leafs capture their third successive Cup.

Food BITE!

Doughnuts were not Horton’s first business venture. In the late 1950s, he ran a service station and car dealership in Toronto. In 1963, he was a partner in an unsuccessful chain of drive-in chicken and burger restaurants in the Toronto area. He also ran a burger outlet in North Bay in partnership with his brother Gerry.

Why did Horton get into the doughnut business? As an investment and because he had a sweet tooth, according to Open Ice: The Tim Horton Story by Douglas Hunter. “I love eating doughnuts and that was one of the big reasons that I opened my first doughnut shop. Buying doughnuts was costing me too much money,” Horton said in 1969.

Until the mid-1980s, the logo found on Tim Hortons signs, coffee cups, bags, and doughnut boxes was Horton’s signature and an oval depicting a stack of four doughnuts, one for each of his daughters. Today, the doughnuts are gone from the company’s advertising but his signature is still on the signs that dot neighbourhoods across Canada.

In the mid-1960s, Horton took over his partners’ shares in the company and soon after met ex-police officer Ron Joyce, who became owner of two Hamilton franchises, including the first one opened by the company. In 1967, Joyce became Horton’s business partner and eventually built the company into one of Canada’s most popular and successful food chains. In 1975, he bought control of the company from Horton’s wife Lori for $1 million and a Cadillac. Twenty years later, the company, then known as TDL Group Ltd., merged with Ohio-based Wendy’s International Inc.

Tim Horton, who launched his successful venture in 1964.

Today, the name that brought hockey fans to their feet in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s is the fourth largest publicly-traded quick service restaurant chain in North America based on market capitalization, and the largest in Canada. As of December, 2008, the chain had 3,437 locations in North America, 2,917 in Canada and 520 in the United States. In 2006, Tim’s opened up a location in a 40-foot trailer on a Kandahar, Afghanistan, military base to give the Canadian troops a taste of home. The company has also entered into a partnership with the SPAR convenience store chain in the United Kingdom and Ireland, where customers that likely include a few ex-pat Canadians can get a Tim Hortons coffee and doughnut from one of the small self service kiosks located in many SPAR stores.

Bruce Druxerman (Druxy’s)

Bruce Druxerman (Druxy’s)

For Bruce Druxerman, the recipe for a successful deli was buns, salami, and experience in banking.

When Bruce Druxerman graduated with a degree in science, commerce, and business administration, he worked in the New York office of the Mercantile Bank of Canada. But later, after he switched his attention to the restaurant business, the Belleville, Ontario, native decided that owning a chain of delis was the way to make his riches. According to The New Entrepreneurs by Allan Gould, Druxerman tried to rent some space in the Royal Bank Plaza in Toronto in 1976, but was told by a realtor that it couldn’t happen because he had no track record.

Druxerman then phoned the bank’s chairman, who was an acquaintance of his father, and the deal was made within a day. The first Druxy’s (Druxerman’s dad had been given the nickname by a neighbour) opened in the fall of 1976, and a profusion of pumpernickel has been served up ever since. Within three years there were 13 Druxy’s in Toronto. Druxerman’s brothers joined the firm, and by the mid-1980s Druxy’s was doing about $20 million in business. There are currently more than 50 Druxy’s locations, mostly in Ontario, with a few in Calgary.

Harvey ____? (Harvey’s)

Harvey ____? (Harvey’s)

Who was the mysterious Harvey?

The man who inspired the name of one of Canada’s leading hamburger and fast food chains likely didn’t know about his claim to fame. And we’ll never be sure if this mysterious Harvey, whoever he was, even bit into one of the juicy burgers that bear his name.

Harvey’s was the brainchild of Toronto-area restaurateur Rick Mauran, who brought charbroiled burgers to Canada in 1959. Although there is something of an urban myth that the chain was named after the title character in the famous Jimmy Stewart movie Harvey, the real story is simpler. Mauran chose the Harvey name after seeing it in a newspaper story. Company history doesn’t provide the context of what the story was even about, but Mauran thought the name had personality, was easy to spell, and memorable. And it was short. Mauran had hired a sign painter for his first restaurant who charged by the letter.

The first Harvey’s opened at 9741 Yonge Street in Richmond Hill, Ontario, where burgers, fries, and onion rings are still hot sellers. Since then, the chain has grown enormously across Canada. Its first franchised restaurant opened in 1962 in Sarnia, Ontario, and by the time CARA Operations Ltd. bought the company in 1979, there were more than 80 Harvey’s restaurants. In 1980, Harvey’s opened Canada’s first drive-thru restaurant in Pembroke, Ontario, and today there are 273 outlets nationwide. More than 7,000 employees serve up close to a million burgers each week.

A few other Harvey’s tidbits to chew on:

• Harvey’s has served up more than one billion burgers since 1959.

• Four out of five guests order pickles on their burger.

• The most frequently requested Harvey’s topping is mustard.

• The northernmost Harvey’s is in Edmonton.

• In 1999, Harvey’s became the first national chain to introduce a veggie burger to its permanent menu.

CANADIAN NAMES IN THE KITCHEN

CANADIAN NAMES IN THE KITCHEN

Canadians spend long hours in the kitchen whipping up favourite dishes for family and friends.

Food BITE!

A road in Barrington, Illinois, is the source for the name of one of Canada’s most popular restaurant chains. Back in the 1970s, when Paul Jeffery and his brother were visiting a friend in Barrington, they frequented a bar on Kelsey’s Road. Jeffery liked the name “Kelsey’s” enough to slap it onto the front of the first roadhouse-style eatery he opened in Oakville, Ontario, in 1978. these days there are over 140 Kelsey’s locations, stretching from Ontario to British Columbia.

And as they’ve steamed, stirred, and sautéed their way into the hearts and stomachs of their loved ones, they’ve encountered names such as Catelli, Goudas, Red-path, Schneider, and Loblaw.

Familiar monikers to be sure, but did you know there were real people behind them with fascinating tales to tell?

Next time you open the cupboard, buy groceries, or reach into the refrigerator, think of the stories of a handful of innovative Canadians who have been putting food on Canadian tables for many years.

Carlo Catelli

Carlo Catelli

Pasta lovers can twirl their forks in thanks to Carlo Catelli. Born in Vedano, Italy, Catelli came to Canada in 1866, and one year later started the Catelli Macaroni Company in Montreal. At first, he needed just three bags of flour a day to satisfy his customers’ palates for pasta, but by the end of the 19th century the business was flourishing and he was a respected leader of the country’s Italian-Canadian community.

Catelli was also a founder of the Chamber of Commerce in Montreal and was its president from 1906 to 1908. He was also created a chevalier of the Crown of Italy in 1904 for his work in building Italian-Canadian relations. Once described as “a respectable gentleman who has achieved commercial success,” Catelli was chosen the Honorary Canadian Representative to the International Exposition in Milan in 1906.

He retired from business in 1910, but continued to be a key figure in the city. At the outbreak of the First World War, the firm was controlled by Tancredi Bienvenu, and by the start of the Second World War, the company not only dominated the pasta and tomato paste market in Canada but had a tremendous presence in Britain, too. In fact, after the war, Catelli and other companies were exporting macaroni to Italy!

During his life, Catelli also helped found an orphanage in the city. The prosperous pasta pioneer died on October 3, 1937, at his home in Montreal on City Hall Avenue and was survived by a son, Leon, and a daughter, Marguerite. He was an important enough business figure beyond Canada to have received a brief obituary in the New York Times.

After Catelli was gone, the company that continues to bear his name dominated the pasta and tomato paste market in Canada. After the Second World War, Catelli products were even being exported to Italy, the home of great pasta. In June 1989, Borden Inc., an American firm, purchased Catelli, and two years later spent $20 million to double production capacity at the Montreal plant.

The Catelli business was sold to H.J. Heinz Inc. in 2001 and they continue to run the division.

William Mellis Christie (Christie, Brown & Company)

William Mellis Christie (Christie, Brown & Company)

Mr. Christie, the man who has filled millions of tummies with cookies, crackers, and snacks, is a Canadian who changed the course of the baking industry in North America. In 1848, at age 19, William Mellis Christie came to Canada from Huntley, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, where he had apprenticed as a baker. He soon formed a partnership with James Mathers and Alexander Brown, working as an assistant baker and travelling salesman. When Mathers retired in 1850, Brown took Christie into the partnership, and 28 years later, Christie became the sole owner of Christie, Brown & Company.

Around that time, Christie attended the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition with samples of his biscuits and returned with silver and bronze medals. He became known throughout Canada for his high quality biscuits that today are found in kitchen pantries from St. John’s to Victoria. In 1900, Christie died of cancer in Toronto and his son Robert took over the business, which at the time employed 375 people and had offices in Montreal and Toronto. In 1928, Christie, Brown & Company was sold to National Biscuit Company (Nabisco) of the United States and has been in American hands ever since.

The company William Mellis Christie founded is now owned by Kraft Foods North America. It operates five biscuit bakeries in Toronto and Montreal, producing such well-known products as Oreo and Chips Ahoy! cookies, Premium Plus and Ritz crackers, and Peek Freans and Dad’s biscuits.

Charles H. Doerr (Dare Foods)

Charles H. Doerr (Dare Foods)

In 1892, Charles Doerr sold everything from soup to nuts at his grocery store in Berlin, Ontario (now Kitchener). But after meeting Ted Egan, a baker from nearby Guelph, Doerr and his associate focussed on making biscuits and candies.

With the opening of C.H. Doerr and Company, the seeds were sown for what would become Dare Foods, a Canadian company with a worldwide reputation for innovation and quality.

Egan eventually left the company and Doerr worked tirelessly to take advantage of the expanding Canadian market from the turn of the century until the First World War. Numerous expansions enlarged the original store on the corner of Weber and Breihaupt streets.

In the early years, Doerr did everything but bake the products. Because there were no supermarket chains or centralized buying groups, biscuits and candies were sold in bulk to individual neighbourhood stores, each visited personally by Doerr. Twice a year he embarked on sales trips to allow local grocers to sample his products.

Popular items were traditional English drop cookies and stamped biscuits; sugar, molasses, and shortbread cookies; and soda crackers. Customers also loved Doerr’s individually hand-stencilled sandwich creams and his marshmallow cookies. The company’s candy line included humbugs, toffees, gum drops, and seasonal specialties such as chocolate-coated marshmallow Easter eggs and Christmas cut rock candy. Many were handmade.

As word of Doerr quality spread, salespersons were hired and sales multiplied across Ontario. Soon, major national retail chains such as Woolworth and Kresge were distributing Doerr products across Canada. In 1919, the company landed a major contract with Hamblin Metcalf (later Smiles and Chuckles) to produce chocolate candies for export to England, added 40,000 square feet of space, and soon after bought modern chocolate-making equipment.

During his life, Doerr was known as responsible and sensible with few extravagances, other than ownership of two cars. He was cheerful and had a pleasant personality and lots of friends, many of whom were also businessmen. He was a commissioner of the Kitchener Public Utilities Commission for 17 years, liked dancing, and was generous to his nine siblings, employing a number of them in his business and supporting the distant ones with annual gifts of money.

Doerr had three wives. The first died at age 58; he then married a long-time family friend who passed away two years later. Doerr’s third wife worked for him in the company office and lived for many years after his death.

The period 1920 to 1945 was among the company’s toughest. The Great Depression caused sales to stagnate; in June 1941, Doerr died at age 72, leaving his firm to his 24-year-old grandson Carl, who had been raised by Doerr and his wife Susannah after his parents died in the great influenza epidemic. In February 1943, Carl watched helplessly as fire destroyed the company factory in the largest blaze in Kitchener’s history.

Using facilities at the Howe Candy Company in Hamilton, Ontario, which had been acquired prior to the fire, Carl Doerr was able to continue production and finance a new plant on Kitchener’s southern outskirts.

In 1945, the company and family names were legally changed to Dare because it was easier to pronounce and was an approximate equal of Doerr in sound.

Since then, the company has been responsible for several innovations in the biscuit and cookie industry, including cellophane packaging; assorted cookie packs, which contain several Dare favourites in the same package; and cookie bags sealed with a wire tie, which enables customers to reseal the bag to retain freshness. Such bags became the standard for biscuit packaging.

Food BITE!

In the tough Depression years, newly hired 16-year-old workers at Dare’s Kitchener factory were paid 17 cents an hour. At the time, Ontario’s minimum wage for adults was 22 cents an hour.

Also unique was the way Dare salespersons were trained to be merchandisers. To help retailers improve sales, they regularly arranged Dare products on store shelves and set up in-store product displays, the first in the industry to take such a hands-on approach.

In 1982, Dare introduced its Breton line of crackers; in 2001, the company completed an acquisition which added Wagon Wheels, Viva Puffs cookies, Grissol Melba Toast, Whippet chocolate-coated mallow cookies, and Loney dried soups and bouillon to its lineup.

In 2002, Dare was chosen as exclusive supplier of cookies for the Girl Guides of Canada, and in 2003 became one of North America’s first major food manufacturers to declare all of its manufacturing facilities “peanut free.”

Charles Doerr.

Photo courtesy of Dare.

The company that Charles Doerr founded was run by fourth generation members of the Dare family, led by president Carl Dare and his sons Graham, executive vice-president, and Bryan, senior vice-president, until 2002. At that time, the first non-family member, Frederick Jacques, was appointed president of operations. Graham and Bryan remain as co-chairmen of the Board of Directors.

The company operates bakeries in Kitchener, Ontario; Montreal, St-Lambert, and Ste-Martine, Quebec; Denver, Colorado; and Spartanburg, South Carolina, and candy factories in Toronto and Milton, Ontario. Its products are sold in more than 25 countries and it employs more than 13,000 people.

Peter Goudas

Peter Goudas

Lovers of ethnic foods can toast Peter Goudas, the brains behind dozens of different canned and bagged goods that bear the Mr. Goudas name. Born in Greece in 1942, Goudas came to Toronto in 1967 with 100 dollars in his pocket and no job prospects. He learned English by watching television and slept on the city’s streets on occasion.

But an idea stirred him that would endear Goudas to cooks everywhere. “There was nobody packaging ethnic food at the time. I knew there was a demand for it. So I said, why not?”

Goudas built an empire of chickpeas, spices, beans, and a wide array of Chinese, Indian, and Caribbean specialties. Today his company services more than 20 chain food stores and 3,000 independent grocers. Food wasn’t his only passion. Goudas also bought a nightclub in 1970, where he played deejay and earned the nickname “Mr. Wu” from patrons who thought he looked “Oriental.”

John Redpath

John Redpath

Cooks who use sugar might want to know the sweet tale of John Redpath, who immigrated to Canada from Scotland in 1816 as a skilled stonemason. One of his early jobs was digging outhouses in Montreal, but he later earned a fortune as a building contractor who helped to construct several buildings at McGill University and portions of the Rideau Canal, among other projects. After the Rideau Canal opened in August 1831, Redpath cooked up a scheme to construct a sugar refinery next to the Lachine Canal in Montreal; it became a city landmark and made him famous. More than 150 years later, Redpath sugar is a mainstay in restaurants, pantries, and grocery stores. A Toronto refinery bearing the founder’s name produces more than 2,000 tons of sugar used for baking and in processed foods, explosives, gasoline additives, paints, and cosmetics. All of their products are made from pure cane sugar.

The Redpath Sugar Museum was established in 1979 to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the company’s sugar refining operation. The free museum is located at 95 Queen’s Quay East in Toronto, Ontario.

The Redpath logo is believed to be the oldest continuously used trademark in Canada.

John McIntosh (McIntosh Apple)

John McIntosh (McIntosh Apple)

In the spring of 1811, John McIntosh stumbled upon a handful of apple tree seedlings while clearing land near Prescott, Ontario, where he planned to establish a farm. Instead of tossing the tiny trees onto a pile of brush that would later be burned, he transplanted them to a nearby garden. McIntosh and his farm in Dundas County south of Ottawa were about to take their place in Canada’s history books.

By the following year all but one of the trees had died. He nursed it and it slowly grew, eventually producing a red, sweet, and crisp fruit with a tart taste.

So began the story of the McIntosh apple, which by the 1960s, accounted for nearly 40 percent of the Canadian apple market and continues to be the most widely grown and sold Canadian fruit. In fact, the Mac has become accepted worldwide and is responsible for much of Canada’s domestic and export apple growing industry. Today, more than three million McIntosh apple trees flourish throughout North America, all stemming from the single tree discovered by McIntosh.

Food BITE!

To this day no one is certain how the orphan tree discovered by McIntosh arrived on his property. Experts speculate that it likely grew from the seeds of an apple core tossed onto the ground by a passerby.

Fifteen years earlier, McIntosh, the son of Scottish Highland parents, had immigrated to Upper Canada from New York State. Eventually he married Hannah Doran and set out to tame the land he had traded with his brother-in-law.

McIntosh’s discovery, near what would eventually become the village of Dundela, would not have been significant if John, and later his son Allan and grandson Harvey, had not nurtured, propagated, and marketed the apple named after his family. In 1835, Allan McIntosh learned the art of grafting and the family began to produce the apples on a major scale.

Despite Allan and his brother Sandy’s efforts, it was many years before the McIntosh Red became prominent. In fact, not until 1870, nearly a quarter of a century after John’s death, was it officially introduced and named. The Mac made its first appearance in print six years later (in Fruits and Fruit Trees of America) and began to sell in large numbers after 1900. The Mac’s hardiness, appearance, and taste made it a contender from birth, but it was only when turn-of-the-century advances in the quality and availability of sprays improved its quality that it realized its incredible commercial potential.

By that time things had changed at the McIntosh farm near Dundela, Ontario. In 1894, a fire burned down the family home and badly damaged the original tree. Though Allan made extensive efforts to nurse it back to health, the historic tree produced its last crop in 1908 and died two years later. Allan died in 1899 and Sandy in 1906, leaving grandson Harvey at the helm when the family apple became world-famous.

Early in the 21st century, the Mac accounted for more than half of the 17 million bushels of apples produced in Canada every year, making it Canada’s most commonly grown fruit. In the U.S. it ranked behind only the two Delicious varieties and has a personal computer named for it; overseas it is one of the few successful North American varieties.

Rose-Anna and Arcade Vachon (Vachon Cakes)

Rose-Anna and Arcade Vachon (Vachon Cakes)

The company that brought Canadians Jos. Louis snack cakes and a variety of other tasty pastries was launched by a modest family with a dream, a bank loan, and a brood of hardworking children.

From its beginnings as a mom and pop bakery operated by Arcade and Rose-Anna in Quebec’s Beauce Region, Vachon Cakes evolved into a multi-million dollar operation, which was referred to by one media commentator as a “treasured morsel of the province’s food industry heritage.”

In 1923, Arcade, 55, and his wife, who was 10 years his junior, left Saint-Patrice de Beaurivage, Quebec, after spending 25 years as farmers there. Under the direction of Rose-Anna, the couple borrowed $7,000 and bought the Leblond Bakery in Sainte-Marie de Beauce, about 60 kilometres from Quebec City. They had 15 dollars in the bank at the time.

Their first employee was their son Redempteur, who made bread, and with his father criss-crossed the surrounding area in a buggy selling loaves for six cents apiece.

As a way to boost sales, Rose-Anna two years later diversified into other baked goods, including doughnuts, sweet buns, shortbread, cakes, pies, and even baked beans, which she made in the wood oven in the kitchen of the family home. Simone, one of two daughters, helped sell the tasty treats after school. In 1928, two of the Vachons’ six sons, Louis and Amédée, returned from the United States to help out. The business prospered when it began exporting to Quebec City.

By 1932, sons Joseph, Paul, and Benoit had also joined the company, which by then had 10 employees and had introduced the Jos. Louis, which soon became its most popular cake. As business grew, trucks were purchased to make deliveries, and trains transported goods to more distant customers. By 1937, the company was peddling its products in Ontario and the Maritimes.

Several significant events occurred between 1938 and 1945: On January 15, 1938, at age 70, Arcade Vachon died. His wife and sons kept the company running and moved to a former shoe factory, where an 8,000-square-foot extension was built and modern production equipment installed. In 1940, the family decided to focus exclusively on snack cakes.

Food BITE!

Some snack lovers believe the Jos. Louis is named after the legendary American boxer Joe Louis. In fact, the chocolate cake’s moniker is a combination of the names of two Vachon sons — Joseph and Louis.

In 1945, at the age of 67, Rose-Anna retired and sold her interest in the company to her sons Joseph, Amédée, Paul, and Benoit, who broadened the product line to 111 different items. Rose-Anna died on December 2, 1948. Two years later a new company, Diamond Products Limited was founded to produce jams for the bakery. It was later sold to J.M. Smuckers of the United States.

In 1961, with its sinfully sweet pastries being sold in most of Canada, the company changed its name to Vachon Inc. By 1970, following several expansions and an acquisition, the company had 12,000 employees. That year, 83 percent of Vachon shares were sold to Quebec banking co-op Mouvement des Caisses populaires Desjardins, leaving 17 percent in the Vachon family’s hands.

Montreal-based food giant Culinar Inc. bought the company in 1977; in 1999, Culinar and Vachon were acquired by dairy and grocery products company Saputo Inc., of Montreal. Despite the corporate shuffle, the Vachon family name is still found on a handful of products made famous by Arcade, Rose-Anna, and their children, including Jos. Louis and May West snack cakes.

The Vachon home in Sainte-Marie de Beauce, Quebec, where Rosa-Anna did her bookkeeping and used her own recipes to bake breads and snack cakes, is a historic monument and museum.

Walter and Jeanny Bick (Bick’s Pickles)

Walter and Jeanny Bick (Bick’s Pickles)

Walter and Jeanny Bick never intended to get into the pickle business. But when warm and humid weather in the summer of 1944 produced a glut of cucumbers, the couple was desperate to salvage tons of cukes before they rotted in their fields.

The Bicks dug out a family recipe from their native Holland and began producing dill pickles in a barn at Knollview, their 116-acre farm in the former suburb of Scarborough, now part of the Greater Toronto Area. “We got into pickles by sheer accident,” said Walter.

The rest, as they say, is condiment history.

The family sold the cattle, chicken, and pigs they’d been raising since Mr. Bick’s parents George and Lena Bick bought the farm in 1939 after coming to Canada from Amsterdam. Instead of selling their cucumbers to stores and markets, they turned them into pickles, said Walter, who apprenticed in the Dutch banking industry before coming to Canada at age 22.

Food BITE!

Like a cucumber on a cutting board, the Bicks’ farm in the former Toronto borough of Scarborough was sliced in two when Highway 401 was built in the mid-1950s.

During the first few years, the Bicks packed their cucumber crop in 50-gallon barrels of brine that were sold to restaurants, butcher shops, and army camps in the Toronto area. In 1952, they entered the retail trade when they packaged whole dills in 24-ounce jars under the Bick’s name, with the now-familiar cucumber in place of the letter i on the labels.

Soon after, the business expanded into a renovated barn on their farm and Canada’s fastest-growing manufacturer of pickles and relishes was on its way to leadership in the Canadian pickle business.

As their business prospered, the Bicks saw many changes: Their product line expanded to include sweet mixed pickles, gherkins, cocktail onions, hot peppers, pickled beets, relishes, and sauerkraut; in 1958 their barn burnt in a fire and was replaced with a modern building. Gradually, sales of their products spread from Ontario to western and eastern Canada and around the world.

Bick’s Pickles brochure.

In 1966, with a staff that ranged between 125 in the summer and 65 in the winter, the Bicks made their biggest change when they sold their company, their farm, and their home to Robin Hood Flour Mills.

Food BITE!

According to Pickle Packers International, Inc., the perfect pickle should exhibit seven warts per square inch for North American tastes — Europeans prefer wartless pickles.

“We sold because the company was bigger than we could handle,” said Walter. “I was never a great delegator. In the beginning, I never realized we needed a sales manager, a purchasing agent but as business increased we had to hire these people … however the family run business way did not disappear.”

Until 2004, Bick’s was a wholly-owned subsidiary of International Multifoods of Wayzata, Minneapolis, whose products included 50 different varieties of Bick’s pickles and relishes, Habitant Pickles, Gattuso Olives, Woodman’s Horseradish, Robin Hood Flour, Monarch Cake & Pastry Flour, and Red River Cereals.

It is now owned by American food company J.M. Smucker Co, which produces Smucker Jams and Jif peanut butter and also owns such iconic brands at Crisco, Robin Hood, Folgers, Pillsbury and Eagle Brand condensed milk.

In addition to more than 30 different varieties of Bick’s pickles and relishes, its consumer products lineup includes pickled hot peppers, beets, and sauerkraut.

Food BITE!

Pickles date back 4,500 years to Mesopotamia, where it is believed cucumbers were first preserved. Cleopatra, a devoted pickle fan, believed pickles enhanced her beauty.

J.M. Schneider (Schneider Foods)

J.M. Schneider (Schneider Foods)

From button manufacturing to the butchering business.

It’s a strange shift in careers, but for J.M. Schneider, whose name today is found on hot dogs, cold cuts, sausages, and other products, it was the route to fame and fortune. John Metz Schneider was born February 17, 1859 in Berlin (now Kitchener), Ontario. He grew up on a farm, looked after the livestock, and helped his parents slaughter and dress the hogs.

As an adult, he found work on the assembly line of the Dominion Button Works earning a dollar a day and working six days a week. When he was 24, he married Helena Ahrens, and they began raising a family. In 1886, Schneider had an accident at the button factory that kept him away from work for about a month. With his hand in a bandage, Schneider, his wife, and his mother began grinding up meat and creating German sausages in their kitchen as a way of earning extra money.

Schneider sold those first sausages door to door, and though he went back to work making buttons, he began building up loyal customers who liked the taste of his sausages. After his long days at the factory, J.M. and Helena would work well into the night trying to make their new venture successful. Eventually J.M. started selling sausages to market butchers and grocers until he reached a point at which he had to choose between the security of buttons and the uncertainty of a new business venture.

When he decided to plunge into the meat business, Schneider turned his house into company headquarters and had a wooden shanty built in the backyard for butchering hogs. By 1891, he had saved enough to build a storey-and-a-half structure in which to operate his business and paid an annual licence fee of 20 dollars to run it. Schneider’s timing was good. Berlin was booming and described around that time as “the most rapidly growing and liveliest town west of Toronto.”

But the early days were still tough, leading Schneider to offer his business for sale. He changed his mind, however, and in 1895 hired a skilled German-trained butcher named Wilhelm Rohleder, who would play a significant role in the company’s growth over the next 45 years. The hard-working Rohleder developed several recipes for Schneider products that made them popular, and he was so secretive about the ingredients that he didn’t even tell J.M.

Schneider, meanwhile, was a hands-on owner from the beginning. He sold his products personally and took the lead in purchasing livestock. When not working, he led a quiet social life playing cards, devoting time to church activities, and enjoying his family. He knew all his workers by their first names and was not one for putting on airs or dressing ostentatiously.

Schneider’s sons followed him into the business when they were old enough and watched it expand in the early 20th century as electricity and refrigeration became essential to the industry. By 1910 Schneider was a wealthy man, but it was the years around the First World War that saw the company expand twentyfold to become a million-dollar business. Despite his wealth, Schneider continued to show up for work every day into his early 80s. He died in 1942, and his epitaph reads “to live in the hearts we leave behind is not to die.”

These days Schneider Foods Inc. remains a mainstay of the Kitchener economy and is a multi-million-dollar enterprise producing a wide range of products across Canada. Its sign on Highway 401 near Guelph, known as the “wiener beacon,” is one of the most recognizable advertising landmarks in southern Ontario.

James Lewis Kraft (Kraft Foods)

James Lewis Kraft (Kraft Foods)

In the world of food products, J.L. Kraft was certainly the big cheese.

His name has become synonymous in Canada and around the world with such famous products as Jell-O, Miracle Whip, and that staple of university students everywhere, Kraft Dinner.

Born in the Niagara region community of Stevensville, Ontario in the 1870s, Kraft was one of 11 children in a Mennonite family who grew up on a dairy farm. When he was 18, he landed a job at Ferguson’s grocery store in Fort Erie, Ontario before investing in a cheese company in Buffalo. In 1903, Kraft moved to Chicago with $65 to his name and decided to rent a wagon and a horse named Paddy. According to company history, Kraft bought cheese every day from the city’s warehouses and resold it to local merchants who didn’t want to make the trip themselves. From this humble beginning, Kraft built up his business to the point that he decided to manufacture cheese and brought in four of his brothers to help him with his enterprise.

Food BITE!

One of Kraft’s hobbies was to make rings with semi-precious stones and give them to employees as awards for their hard work. He had to abandon the idea as the number of workers began to grow.

In 1909, JL Kraft and Brothers Co. began importing cheeses from Europe, but it was Kraft’s dream to make cheese that would keep longer, cook better, and be packaged in convenient sizes. At the time, cheddar cheese, the most popular variety in the U.S., moulded or dried quickly and was difficult to ship long distances. As Kraft continued to sell different cheeses, however, he experimented with ways of making cheese a more marketable commodity. Kraft sold $5,000 worth of pasteurized cheese in 1915, and the next year sales jumped to $150,000.

The year 1916 would be the key one in Kraft’s life. He received a patent for what would become known as processed cheese, narrowly beating out another company that was working on a similar process. To his credit, Kraft would later share the patent rights with the company.

Four years later, Kraft entered the Canadian market selling processed cheese and bread on a national scale. The famous Kraft kitchens were also started in the 1920s, and some of the products resulting from this approach were Miracle Whip in 1933 and Kraft dinner in 1937. It was said that by the 1930s, Kraft was selling three million pounds of cheese a day. Per capita cheese consumption in the U.S. increased by 50 percent between 1918 and 1945, largely because of Kraft’s efforts and innovations.

Kraft was also an innovator when it came to advertising. As early as 1911, he was advertising on Chicago’s elevated trains, using billboards, and mailing circulars to retailers. He was among the first to use coloured ads in magazines, and in 1933 the company began using radio to advertise its products by sponsoring the Kraft Musical Review. Though he was in his seventies by the time television arrived, Kraft embraced the new medium and created the Kraft Television Theatre.

The company prospered throughout his life, and by the time Kraft died in 1953, the firm had become one of the most recognizable brand names in the world. The company merged with General Foods in 1989 and continues to produce an array of famous products including Minute Rice, Cool Whip, Maxwell House coffee, and Tang.

Not bad for a young man who started out with less than 100 dollars in his pocket.