TEN TRANSPORTATION TIDBITS

TEN TRANSPORTATION TIDBITS  TEN TRANSPORTATION TIDBITS

TEN TRANSPORTATION TIDBITS

• The Peterborough Lift Lock on the Trent-Severn Waterway at Peterborough, Ontario, is the highest hydraulic lift in the world. Work began in 1896, and when the job was completed in 1904 it enabled boaters to overcome a difference in elevation of more than 19 metres between Little Lake and Nassau Mills.

• Canada has more than 900,000 kilometres of roads and highways and a national highway system that is more than 24,000 kilometres in length.

• The idea of having white lines down the middle of highways is thought to have originated near the Ontario-Quebec border in 1930. J.D. Millar is credited with introducing the lines; his boss at the Ministry of Transportation thought the innovation was foolish.

Hundreds of highways criss-cross Canada for thousands of kilometres.

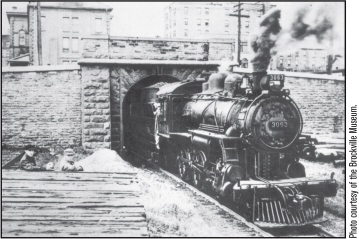

• The first train tunnel in British North America was built in Brockville, Ontario, between 1854 and 1860. The Brockville Railway Tunnel enabled Grand Trunk Railway trains to travel through a wedge of rock to the nearby waterfront. Victoria Hall, Brockville’s city hall, was constructed on top of the tunnel in the early 1860s.

• The first airmail flight in Canada took place in 1918. A military aircraft took off in Montreal in the morning with 120 letters, refuelled in Kingston, Ontario, and made its delivery in Toronto late that afternoon.

• The first electric streetcar system in Canada was installed in Windsor, Ontario, in 1886, whereas Toronto’s wasn’t in place until 1892. By the First World War, 48 Canadian cities and towns had streetcar systems.

The Brockville Railway Tunnel.

• At the time of Confederation, the Grand Trunk Railway, which ran from Montreal through parts of southern Ontario and included links to the U.S., was the largest railway system in the world.

• When the Canadian Pacific Railway introduced the streamlined, all stainless steel transcontinental train The Canadian on April 24, 1955, the rail trip between Montreal and Vancouver was reduced to 71 hours and 10 minutes. That’s 16 hours less than previous trains took to make the trek.

• The first steam locomotive manufactured in Canada was built in 1853 by James Good of Toronto. It was named Toronto and was part of the great flurry of industrial activity that marked the country’s first great railway boom in the 1850s.

• Toronto’s Yonge subway was the first subway line built in Canada. It was constructed between 1949 and 1954 and officially opened on March 30, 1954. It initially ran from Eglinton to Union Station, a trip that took about 12 minutes.

BREAKING NEW GROUND

BREAKING NEW GROUND

First Train Across Canada: Chugging into History

First Train Across Canada: Chugging into History

On June 28, 1886, nearly eight months after the last spike was driven at Craigellachie, British Columbia, the first transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railways train left Montreal for the Pacific Ocean.

At noon hour on July 4, 1886, Train No. 1, the Pacific Express, with 150 passengers on board, rolled into Port Moody, B.C. It was an occasion one history book described as “the most significant event in the history of Port Moody.” The 2,892.6-mile trip across four time zones took 139 hours.

Whatever happened to the train that made the first trip across Canada on the brand new east–west rail line?

Trivia BITE!

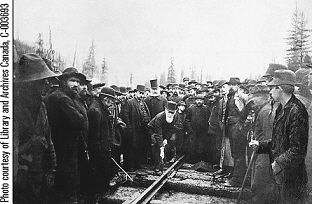

Lord Strathcona drove the last spike in a ceremony at Craigellachie, British Columbia, thus completing the Canadian Pacific Railway. The spike was made of iron, not silver or gold as some have thought.

Bring the hammer down … let the trains roll.

For starters, only two of the 10 cars that made up the train as it left Montreal — the Honolulu, a sleeper car and Car 319, carrying mail, express, and baggage — made the entire westward journey. Other cars were picked up and dropped off along the way; as the train made its way across Canada, its locomotives were changed more than two dozen times.

Locomotive 371, which was placed on the train at North Bend, B.C., just east of Port Moody, was the engine chosen to pull the first transcontinental train into the terminal at Port Moody, where Vancouver-bound passengers were transferred to a stage coach for the final 12-mile leg of the trip.

According to the Canadian Pacific Archives, Locomotive No. 371, which was built in Montreal in 1886, was scrapped in October 1915. The baggage, mail/express car, which was built in 1884 by the CPR at its Hochelaga shops, was renumbered several times before being scrapped in 1937 at Montreal. The Honolulu, built in 1886 by Barney & Smith, was renamed Pembroke in 1918, renumbered 1705 in 1926, then scrapped in 1930 at Montreal.

The first engine and rail cars to arrive on the west coast may be long gone, but another engine of significance is still intact and honoured for its historic role: Locomotive No. 374, which on May 23, 1887, became the first engine to haul a train into Vancouver once tracks were extended from Port Moody, is on display at the Roundhouse Community Arts and Recreation Centre in Vancouver.

The locomotive was extensively rebuilt in October 1915 and remained in service until July 1945, when it was retired and donated to the City of Vancouver, says CP Archives.

In the 1980s, the West Coast Railway Association and the Canadian Railroad Historical Association undertook a round of cosmetic work that restored No. 374 to the way it looked in 1945.

For more information, visit www.roundhouse.ca or www.seevancouverheritage.com/eng374/eng374.htm.

Casey Baldwin’s Airplane: First in Flight

Casey Baldwin’s Airplane: First in Flight

Frederick “Casey” Baldwin gained fame on March 12, 1908, when he flew about 97 metres (319 feet) in a biplane over icy Keuka Lake in Hammondsport, New York. By doing so, Baldwin became the first Canadian to fly an airplane.

Though he wasn’t the first to fly on Canadian soil — that would happen the following year when John McCurdy piloted the Silver Dart in Nova Scotia — Baldwin earned his place as one of the key pioneers in aviation history. His flight, watched by several spectators, is considered the first public heavier-than-air airplane flight in U.S. history. The Wright brothers’ flight in 1903 was very much a private affair.

According to accounts, Baldwin got to fly the plane, named the Red Wing, because on the frigid day he was the only one of the aviation team who wasn’t wearing ice skates. Since he was slipping on the ice, the others decided he would be most useful sitting in the cockpit. The flight had been more than a year in the making since Alexander Graham Bell established the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), whose purpose was to build a practical airplane for $20,000.

The Red Wing, designed by American Thomas Selfridge and so named because of the red silk that covered its frame, flew only some five to 10 feet off the ground during Baldwin’s sojourn but made a smooth landing. There was a small story about the flight on the front page of the next day’s New York Times, but Baldwin’s name wasn’t mentioned. The Red Wing’s final flight, five days later on March 17, was not as successful. A stiff breeze caught the plane after about 120 feet in the air and sent it and Baldwin to the ground. Although Baldwin escaped injury, the plane’s motor and wing were damaged beyond repair.

Over the next two months, the AEA team built a second plane, the White Wing, which had considerable success. Accounts from the time make no mention of what happened to the wreckage of the Red Wing, however. Was any of it salvaged and used elsewhere? Or was it simply left to the elements? At any rate, the Red Wing remains a key piece of the history of flight, and photographs of it exist to this day

Baldwin would go on to make more flights and sit as a politician in the Nova Scotia legislature before dying in 1948. Selfridge, unfortunately, suffered a cruel fate. In September 1908, during a flight in which he was a passenger, the plane crashed, severely injuring him. He later died in surgery, thus becoming the first airplane fatality in the world.

Canada’s First Automobile: Full Steam Ahead

Canada’s First Automobile: Full Steam Ahead

In 1867, Canada’s first self-propelled automobile was demonstrated at the Stanstead Fair in the community of Stanstead Plain, southeast of Montreal.

The vehicle, invented by watchmaker Henry Seth Taylor, was powered by steam, had no brakes, and could reach a top speed of just 15 miles per hour.

Despite Taylor’s pioneering efforts, it was the subject of considerable ridicule from townsfolk who considered it a “toy of exaggerated size and power,” according to an article published by the Antique Automobile Club of America in 1968.

Nevertheless, a local newspaper called the steam car “the neatest thing of the kind yet invented” and Taylor boasted that his vehicle would challenge “any trotting horse.”

The basis of the car, which Taylor started building in 1865, was a high-wheeled carriage with some bracing to support a two-cylinder steam engine mounted under the floor. Steam was generated in a vertical coal-fired boiler mounted at the rear of the vehicle behind the seat. The boiler was connected by rubber hoses to a six-gallon water tank located between the front wheels. Forward and reverse movements were controlled by a lever, and a vertical crank connected to the wheels was used for steering.

Road BITE!

Canada’s first concrete highway was built between Toronto and Hamilton in 1912 to accommodate a tremendous increase in traffic. In 1907, there were 2,130 cars on Canada’s roads; five years later, when the concrete highway was opened to traffic, 50,000 cars were in use.

The vehicle’s lack of brakes proved to be its undoing. After driving it for several years and showing it off at carnivals and parades, Taylor lost control one summer day as he drove down a hill. Before he came to a stop, the car had turned on its side, its wheels shattered.

Discouraged, Taylor put the remains in a barn near Stanstead Plain, where they sat until the early 1960s when Gertrude Sowden of Stanstead purchased the property. She recognized the value of Taylor’s creation, but when she couldn’t interest museums in it, she sold the remains to American Richard Stewart of Middlebury, Connecticut, president of Anaconda American Brass.

Eventually new wheels were made, the seat and dashboard were recovered with leather, all wooden parts were scraped, sanded, and repainted, and brakes were added. None of the engine parts needed replacing.

The Taylor steam car was acquired by the Canada Science and Technology Museum in Ottawa in 1984. Although it is on exhibit from time to time, the vehicle spends much of its time in a climate-controlled warehouse adjacent to the museum, where public access can be arranged by appointment.

In the summer of 2005, the vehicle was shown four times, twice to individuals and twice as part of a larger tour of the warehouse.

“Looking at the vehicle, one sees the origins of the automobile, even though it predates the blossoming of the auto industry by 40 years,” we were told by Garth Wilson, curator of transportation at the Ottawa museum. “It is absolutely significant in that it is first Canadian made auto and, as such, represents Canada’s entry into world of automobiles.”

For more information, visit http://www.sciencetech.technomuses.ca or call (613) 991-3044.

The Merchant Ship Simcoe: First into the St. Lawrence Seaway System

The Merchant Ship Simcoe: First into the St. Lawrence Seaway System

The St. Lawrence Seaway opened for business on the morning of April 25, 1959, when the bulk carrier Simcoe, commanded by Captain Norm Donaldson, entered the waterway from the eastern end at the St. Lambert lock on the south shore of Montreal.

There will always be debate over who invented the world’s first self-propelled automobile, but one thing is certain: Canada’s Henry Seth Taylor is in good company. The French say one of their countrymen, inventor Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot, built the world’s first self-propelled mechanical vehicle, “Fardier à vapeur” (steam wagon), in 1769. German Karl Benz, generally thought to be the father of the practical motorcar in Europe, unveiled his first vehicle, a three-wheeled, gas-powered car known as “Benz Patent Motor Car” in 1886. American Henry Ford’s initial vehicle was the gasoline-powered Quadracycle, first sold in 1896.

Simcoe, then owned by Canada Steamship Lines (CSL), was the first commercial vessel to transit the seaway, which had been five years in the making and soon became a vital artery that enabled industries in North America’s heartland to compete in export markets.

Among Simcoe’s passengers was T.R. McLagan, president of CSL. Prime Minister John Diefenbaker was aboard Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker d’Iberville, which also entered the seaway on opening day.

Trivia BITE!

Simcoe was the first merchant ship to enter the St. Lawrence Seaway but was not the first vessel to transit the waterway. That honour goes to the icebreaker d’Iberville, which entered the seaway on April 25, 1959, just ahead of Simcoe. Built in 1953 by Davie Shipbuilding & Engineering Co. Ltd. for Transport Canada’s Canadian Marine Service (later known as the Canadian Coast Guard), d’Iberville spent much of its life in the Arctic, where it activated navigational aids and delivered supplies to outposts. It also escorted ships in the St. Lawrence River and cleared ice jams to prevent flooding. The d’Iberville was retired at the end of 1982, put up for sale a year later, and scrapped in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, in 1989.

At the time, the 259-foot-long Simcoe was a CSL stalwart entering its 33rd year of service for the company. It and other ships of its size would soon be replaced by much larger lakers designed to maximize the increased size allowances offered by the seaway.

The ship was built in England in 1923 by Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson Ltd. and was known as Glencorrie under its first two owners, Glen Line Ltd. of Midland, Ontario, and Geo. Hall Coal & Shipping Corp. of Montreal. In 1926, it was purchased by CSL and its name was changed to Simcoe.

During the Second World War, the ship was chartered by the Canadian government to transport supplies for the military and was one of a handful of bulk carriers to avoid being sunk by enemy torpedoes.

It was owned by CSL until 1961 before being sold to Simcoe Northern Offshore Drilling Ltd. of Kingston, where it was converted to a drilling barge and renamed Nordrill.

In 1977, 18 years after making history as the first bulk carrier to enter the St. Lawrence Seaway, Simcoe was scrapped at Port Colborne, Ontario.

World’s First Motorized Wheelchair

World’s First Motorized Wheelchair

Recognizing the difficulties faced by veterans disabled in the Second World War, Canadian inventor George Johnn Klein invented the world’s first electric wheelchair.

The Hamilton inventor, whom the Canadian Encyclopedia describes as “possibly the most productive inventor in Canada in the 20th century,” was able to overcome challenges faced by others with an innovative 24-volt power system, separate and reversible drive units for each of the two main wheels, and an easy-to-use joystick-style control throttle.

The Canada Science and Technology Museum in Ottawa has called the wheelchair “one of the most significant artifacts in the history of Canadian science, engineering, and invention.”

It was developed by Klein at the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) in Ottawa in collaboration with Veterans Affairs Canada and the Canadian Paraplegic Association. But, alas, the chair would be produced in the United States instead of Canada.

In the early 1950s, no Canadian manufacturers were able to mass produce the device, so to promote the technology the electric prototype was presented to the United States Veterans Administration at the U.S. Embassy in Ottawa on October 26, 1955. A year later, a California company began churning out motorized wheelchairs.

The prototype wheelchair has been a coveted possession of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History since 1979. However, it was “repatriated” and has been on display at the Canada Science and Technology Museum in Ottawa since 2005.

Over the years, countless people in Canada and around the world have benefited by having access to the Klein wheelchair.

“It has all of the elements of a significant invention,” says Randall Brooks, assistant director of the Collection and Research Division at the Canada Science and Technology Museum. “It freed the disabled up to be independent because previously, anyone who did not have the use of one or both hands was completely reliant on someone else to get around.

It allowed people to get out and work, to make a living and contribute to society.”

Described in a June 2004 report in the Ottawa Citizen as “a clunky looking thing, a far cry from the sleek and speedy mobile machines used today,” Klein’s chair attracted international attention with its innovative controls, ease of operation, flexible drive system, and dependability.

Klein has been hailed as one of Canada’s most remarkable engineers. He also invented medical suturing devices, Canada’s first wind tunnel, and gearing systems for the Canadarm used on several U.S. space shuttle missions. He died in 1992.

For more information, visit the Smithsonian Institution at www.si.edu or the Canada Science and Technology Museum at www.sciencetech.technomuses.ca or call (613) 991-3044.

THE TRANSPORTATION BUSINESS

THE TRANSPORTATION BUSINESS

Joseph-Armand Bombardier (Bombardier Inc.)

Joseph-Armand Bombardier (Bombardier Inc.)

As a young lad of 14, Joseph-Armand Bombardier had a decision to make: Would he forge ahead with his religious studies and become a priest, or pursue his passionate interest in mechanics?

People whose world is covered with snow most of the time should be glad Bombardier chose mechanics.

In 1922, the boy who for years had amazed his family and friends by building toy tractors and locomotives out of old clocks, sewing machines, motors, and cigar boxes built his first snowmobile.

The prototype, tested with his brother Leopold, consisted of a four-passenger sleigh frame supporting a rear-mounted Model T engine with a spinning wooden propeller sticking out the back. As dogs barked and onlookers demanded they shut it down, the noisy and extremely dangerous contraption made its way along the streets of Valcourt in Quebec’s Eastern Townships, where Bombardier had been born on April 16, 1907.

He was only 15, but Armand had begun his lifelong infatuation with the concept of a vehicle that would travel on snow and offer relief for country folks isolated during Quebec’s harsh and snowy winters.

Two years later Bombardier dropped out of the St. Charles Baromée seminary in Sherbrooke, Quebec, and started working on engines, eventually moving to Montreal where he registered for evening courses in mechanics and electricity. He soon landed a job in a large auto repair garage as a first-class mechanic.

In 1926, with a wealth of theoretical and practical training under his belt, the 19-year-old Bombardier returned to the Valcourt area, where he opened Garage Bombardier. He was a dealer for Imperial Oil and fixed cars, as well as threshers, ice saws, and pumps. His reputation as a mechanic who could diagnose and resolve most mechanical problems quickly helped the business flourish, so much so that he hired several friends and family members to help out.

Trivia BITE!

In the late 1950s, the list price of a Ski-Doo was about $900. Today’s models range in price from $8,000 to $13,000.

His strength was his inventiveness: He built equipment with his own hands, once forging a drill and hydraulic press for producing steel and cast iron cylinders, gas tanks, and heaters. He also built his own dam and turbine to harness energy for his own use, long before the town of Valcourt introduced electricity.

After marrying Yvonne in 1929, Bombardier turned to the development of a motorized snow vehicle to replace the horse-drawn sled, which was a slow and inefficient mode of winter travel when snow made roads impassable in Quebec. For years, he wrestled with three key challenges — even distribution of the vehicle’s weight to keep it level on snow, a safe and reliable propulsion engine, and suspension that would afford passengers a comfortable ride.

A tragedy in his own family played a role in the invention of his first commercial product. In January 1934, Bombardier’s two-year-old son Yvon needed immediate hospital treatment for appendicitis and peritonitis. But with roads blocked by snow, there was no way he could get the boy to the nearest hospital, 50 kilometres away in Sherbrooke, Quebec. The death of his son made Armand all the more determined to create a snow machine that would help Quebecers avoid similar tragedies.

Two years later Bombardier invented the B7, which stood for Bombardier and the seven passengers it could carry. With its lightweight plywood cabin, many said it resembled a futuristic tank on skis. He received a patent in June 1937, for his invention of a sprocket device that made the vehicle travel over snow, and production began under the business name L’Auto-Neige Bombardier Limitée.

The B7 sold for slightly more than $1,000, “about the same price as low-end automobiles of the time,” writes Larry MacDonald in his book The Bombardier Story.

During the Second World War, a variety of models were built and the company erected new factories and added staff. After the war, production soared to 1,000 units a year. In 1947–48, multiple-passenger vehicles were the company’s mainstay and had boosted sales to $2.3 million when two events hit the company hard: The winter of that year was virtually snowless in Quebec, and the provincial government committed to keep all major roads clear of snow every winter. As a result, L’Auto-Neige Bombardier’s sales dropped by 40 percent to $1.4 million in 1948–49.

These events convinced Bombardier of the need for smaller snowmobiles for people who travelled alone, such as doctors, trappers, and prospectors. He began working on prototypes and meanwhile, the company diversified into all-terrain vehicles for the mining, oil, and forestry industries, eventually developing the Muskeg Tractor, which was unveiled in 1953 to transport supplies over snow and swamps.

Bombardier’s greatest breakthrough came in 1959, when after a long struggle to overcome financing issues and design problems, the company unveiled a small, lightweight snowmobile powered by a reliable two-cycle engine and utilizing a seamless, wide caterpillar track invented by his eldest son Germain. It was an instant hit.

In the February 1963 issue of Imperial Oil Review the machine was described as a “kind of scooter mounted on toy tracks and which growls like a runaway dishwasher.” Bombardier’s invention opened up communities across northern Canada in winter and introduced Canadians to a new winter sport — snowmobiling.

Bombardier died of cancer on February 18, 1964 at the age of 56, but not before being granted more than 40 patents and developing a robust business with sales of $10 million. Today, many of his inventions can be seen in the J. Armand Bombardier Museum in Valcourt, Quebec.

Trivia BITE!

When Armand Bombardier invented the snowmobile in 1959, he called it the Ski-Dog, but when the literature was printed, a typographical error changed the name to Ski-Doo. It stuck, and since that faux pas the company has sold more than two million snowmobiles worldwide.

Following his death, the company — now known as Bombardier Inc. — diversified further to become Canada’s most important transportation conglomerate under the guidance of Germain Bombardier, and later Laurent Beaudoin, Joseph-Armand Bombardier’s son-in-law. By the 1990s, more than two million snowmobiles had been sold and the Montreal-based company was also producing the Sea-Doo recreational watercraft, boats, and all-terrain vehicles. The firm had worldwide manufacturing interests in airplanes, trains, military vehicles, and public transportation systems. In the fiscal year that ended January 31, 2008, they posted revenues of US$17.5 billion.

Samuel Cunard (Cunard Line)

Samuel Cunard (Cunard Line)

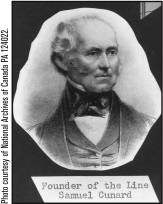

By the time Samuel Cunard died in London at age 78, he had transformed the way ships navigated the world’s oceans.

The Halifax-born son of a master carpenter and timber merchant, Cunard created a shipping line that operated the finest passenger liners in the world and dominated Atlantic shipping in the 19th century. Among its ships were the Lusitania and the Queen Elizabeth.

The hallmarks of the company were safety over profits, the best ships, officers and crew, and a handful of shipping innovations that contributed to the improvement of international navigation.

As a youngster, Cunard demonstrated remarkable business acumen. At age 17, he began managing his own general store and after joining his father in the timber business, he gradually expanded the family interests into coal, iron, shipping, and whaling. A. Cunard and Son opened for business in July 1813, and a year later its ships were carrying mail between Newfoundland, Bermuda, and Boston. Soon, the fleet numbered 40 ships.

Early in his career, Samuel Cunard recognized the economic disadvantages of ships entirely dependent on wind. He dreamed of a steam-powered “ocean railway” with passengers and cargo arriving by ship as punctually and as regularly as by train.

Although his idea was greeted with scorn, in 1833, the Royal William became the first ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean entirely by steam. Cunard was one of the vessel’s principal shareholders.

In 1839 Cunard won a contract to undertake regular mail service by steamship from Liverpool to Halifax, Quebec City, and Boston. With associates in Glasgow and Liverpool, he established the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, the direct ancestor of the Cunard Line. Four steamships were built, and in July 1840, paddle steamer Britannia crossed the Atlantic from Liverpool to Halifax, and steamed on to Boston in 14 days and eight hours, a feat that would lead to the decline and eventual disappearance of transatlantic commercial sailing ships.

In addition to an unparalleled safety record, Cunard’s company was on the leading edge of shipping innovation, initiating the system of sailing with green lights to starboard, red to port, and white on the masthead, which became the standard for the entire maritime world. Its ships were also the first to enjoy the marvels of electric lights and wireless.

Samuel Cunard.

Trivia BITE!

Not a single life was lost on a Cunard ship in the first 65 years of the company’s history until May 7, 1915, when a German submarine torpedoed the Lusitania, killing 1,200 people. The disaster occurred 50 years after Cunard’s death. Writer Mark Twain once remarked that “he felt himself rather safer on board a Cunard steamer than he did upon land.”

Cunard’s enlightened views as an employer were far ahead of his time. It was always his view that if he picked employees well, paid them well, and treated them well, they would return the favour with loyalty and pride — and they did.

In 1859, Cunard was honoured by Queen Victoria with a knighthood. He died in 1865. The Cunard group became a public company in 1878, adopting the name Cunard Steamship Limited, and eventually absorbed Canadian Northern Steamships Limited and its principal competitor, the White Star Line.

The company is now known as the Cunard Line and is operated by Miami-based Cunard Line Limited. Its flagship is the luxury cruise ship Queen Elizabeth 2, which the company touts as “the world’s most famous ship and the greatest liner of her time.”

The Popemobile: Designed to Withstand a Commando Attack

The Popemobile: Designed to Withstand a Commando Attack

They were two Canadian-made vehicles specially adapted for Pope John Paul II’s 1984 visit to Canada. Not surprisingly, they were known as “Popemobiles.”

They were used during the late pope’s September 1984 papal tour of Canada, after an assassination attempt in 1981 prompted the Vatican to demand more protection for the pontiff. One was also used by the Pope when he visited Cuba in 1998.

Both Popemobiles were built by Camions Pierre Thibault, a Pierreville, Quebec, emergency vehicle maker well known for its fire trucks. They’re modified GMC Sierra Heavy-Duty V8 trucks with a large transparent dome designed to keep the Pope fully protected and comfortable, yet completely visible.

The dome area is fully air-conditioned, and is upholstered in red velvet imported from France. The $15,000 trucks were donated by GM Canada, and the 3.2-centimetre-thick bulletproof glass is made of a special laminate valued at $42,000 and donated by GE Canada.

The cube area accommodated the Pope and four other people. The trucks were equipped with video cameras, which produced footage that was sold to the media and used for security. Total cost for each vehicle was $130,000.

Originally the property of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, one Popemobile was donated to the Canada Science and Technology Museum in Ottawa in 1985, where it is occasionally placed on display. While in storage the vehicle can be viewed by appointment only by calling (613) 991-3044. The other Popemobile is at the Vatican in Rome.

QUIZ: YOU AUTO KNOW

QUIZ: YOU AUTO KNOW

A chance to test your knowledge of Canada’s highways and byways.

1. The early 1960s slogan “Put a Tiger in your Tank” was the brainchild of what automobile fuel company?

a) Supertest

b) Imperial Oil

c) Fina

d) Texaco

2. True or false? In 1903, when Canada’s first automobile clubs were founded, there were fewer than 200 cars in the country.

3. In 1900, F.S. Evans set a speed record for the 60-kilometre trip by automobile between Toronto and Hamilton. How long did it take him?

a) 90 minutes

b) one hour

c) two hours and 45 minutes

d) three hours and 20 minutes

4. What city hosted Canada’s first automobile race?

a) Montreal

b) Halifax

c) Winnipeg

d) Toronto

e) London

5. What is Canadian driver Earl Ross’s claim to fame?

a) he was once NASCAR ’s Rookie of the Year

b) he won the first Can-Am race in the 1960s

c) he won a race against an airplane in 1917

d) he was the first Canadian to compete in the Indy 500

6. The Peck was an electric car built in Toronto from 1911 to 1913. What was the company’s slogan?

a) “This car Pecks a punch.”

b) “Keeps pecking.”

c) “A Peck of a smooth ride.”

d) “Drive a Peck today.”

7. What is the name of the scenic drive between banff and Jasper national parks?

8. true or false? ontario was the first province to establish a department of highways.

9. in 1991, Petro-canada announced one of the following. Was it:

a) a new consumer-friendly credit card

b) canada’s first customer rewards program

c) the sale of its shares to the public

d) development of a revolutionary touch-free car wash system

10. the University of british columbia’s sports teams have the same name as a popular sports car. What is it?

GET OUT ON THE HIGHWAY

GET OUT ON THE HIGHWAY

• Canada boasts the longest highway in the world, the Trans-Canada Highway at 7,821 kilometres in length, as well as one of the busiest sections of highway in the world, Highway 401 through the Greater Toronto Area. On a typical day, more than 400,000 vehicles use Highway 401 where it intersects with Highway 400.

• On May 1, 1900, in Winnipeg a horse buggy and a car collided in what was Canada’s first recorded auto accident. No word on who got the worst of it.

• In 1903, Ontario became the first province to issue car licences, which took the form of patent leather plaques with aluminum numbers. At the time, other provinces issued individual motorists a number for their vehicle and left it to the owners to make their own plates, usually from wood, metal, or leather.

• At one time in British Columbia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland, and Nova Scotia motorists used to drive on the left side of the road. British Columbia was the first to make the switch to the right side in 1920, followed by Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and PEI over the next four years. For months after the change, road signs in Nova Scotia warned motorists to stay to the right. Newfoundlanders did not switch to the right side of the road until 1947 in preparation for entering Confederation with Canada in 1949.

• Dr. Perry Doolittle, a native of Elgin County in southwestern Ontario, founded the Canadian Automobile Association in 1913 and was the first physician in Toronto to make his rounds by automobile. He is also the man who bought the first used car in Canada, a one-cylinder Winton, from owner John Moodie of Hamilton. Doolittle was president of the CAA from 1920 to 1933.