Country of origin: Germany

Date of manufacture: c. 1914–15

Location: Private collection

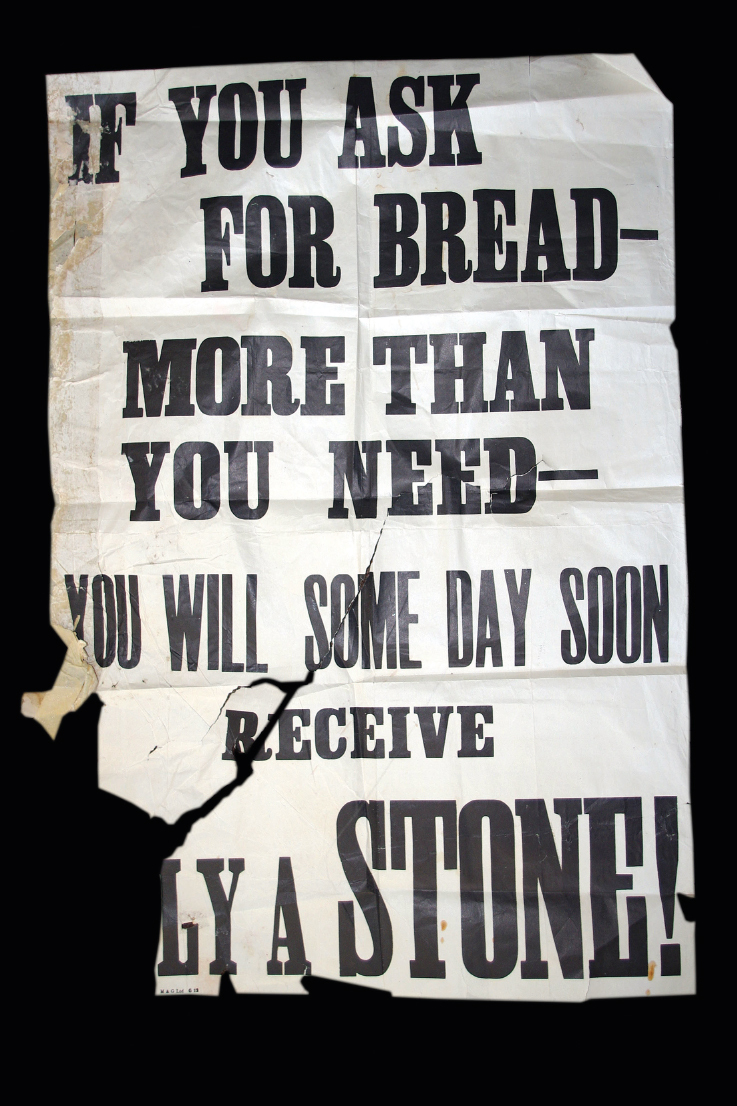

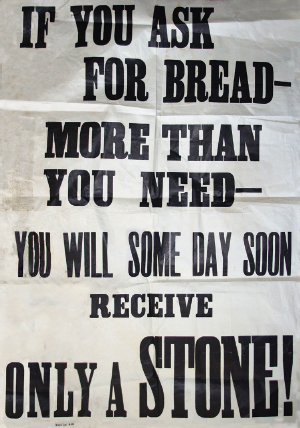

THE WAR WAS never going to be a short affair. With rapidly spiralling costs, the burden of paying for it would have to be met by the public. In Britain, for instance, while the cost of the war was estimated at £1 million per day in 1914, by its end, this had increased to around £5.7 million. Taxation could only go so far, so money had to be raised through the issue of War Bonds – Kriegsanleihe in Germany and Austria – which required personal investment in the national scheme, with the promise of rewards later. In most cases, and in all countries, War Bonds were portrayed as part of the patriotic duties of the people. In Germany, a total of nine War Bonds were issued between 1914 and 1918 that earned 98 billion Reichsmarks, which covered some 60 per cent of the war costs. And, while most belligerent countries depended on similar schemes, there is one that was typical only of Germany: the concept of freely ‘giving gold for iron’.

There was a precedent. On 31 March 1813, during the Napoleonic Wars, Princess Marianne of Prussia personally appealed to all Prussian women to hand in gold jewellery for their country in order to finance the campaigns. In exchange they received simple iron jewellery marked ‘Gold I gave for iron’ or ‘Gold for defence; iron for honour’, and very quickly the wearing of iron rings, earrings and bracelets became fashionable. With a world war in progress, the appeal was repeated in 1914, and with similar success. Though voluntary, there was huge social pressure on people to hand in their gold: watch chains, rings, jewellery of all types. The system was simple: if you wore iron jewellery you were a patriot; if you were still wearing gold, you were a traitor.

The medallion illustrated was handed out by the Reichsbank in exchange for not only gold, but also silver and bronze. It depicts a person offering gold ‘In eiserner zeit’ (In iron time), and carries the message ‘gold gab ich zur wehr eisen nahm ich zur ehr’ (gold I gave to the military I took iron). The medal was designed by the German artist and sculptor Kurt Hermann Hosaeus (1875–1958). Gold was not only given by individuals but also by institutions such as churches and public offices. Appropriately enough for a city associated with steel, in 1917 the Mayor of Magdeburg donated the city’s seventeenth-century golden chain of office in support of the war effort; the iron chain given in exchange is still in the local museum.

For the Germans, iron had a deep meaning, linked directly to Germanic mythology. During the Iron Age the process of melting and forging iron was thought to be a mystical process: few people knew the secrets that made it possible to forge weapons of iron, and with human blood tainted with the smell of iron, so this metal was considered to be the blood – or life force – of the Earth. A popular nationalistic song, Der Gott der Eisen wachsen ließ (The God that made the iron grow), written by Ernst Moritz Arndt in 1812, begins with the words: Der Gott der Eisen wachsen ließ, der wollte keine Knechte. Drum gab er Säbel, Schwert und Spieß dem Mann in seine Rechte (It was the God who let iron grow and wanted no slaves, who therefore armed the Germans with sabre, sword and spear). Giving gold for iron meant much more to the German public than simply funding the war; it meant the direct defence of the Fatherland.

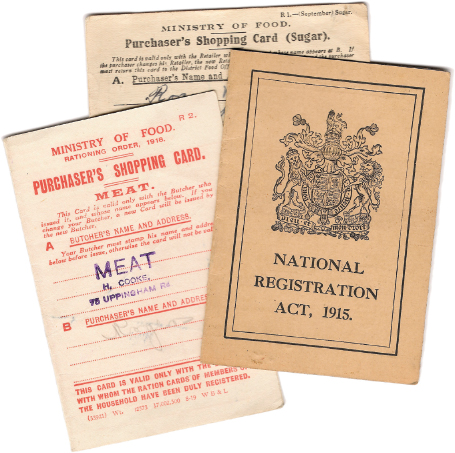

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Date of printing: 1915

Location: Private collection

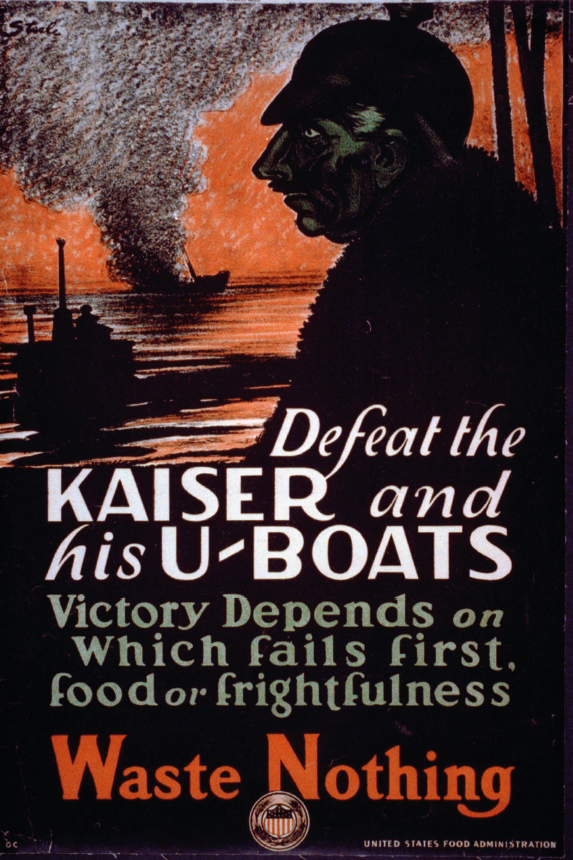

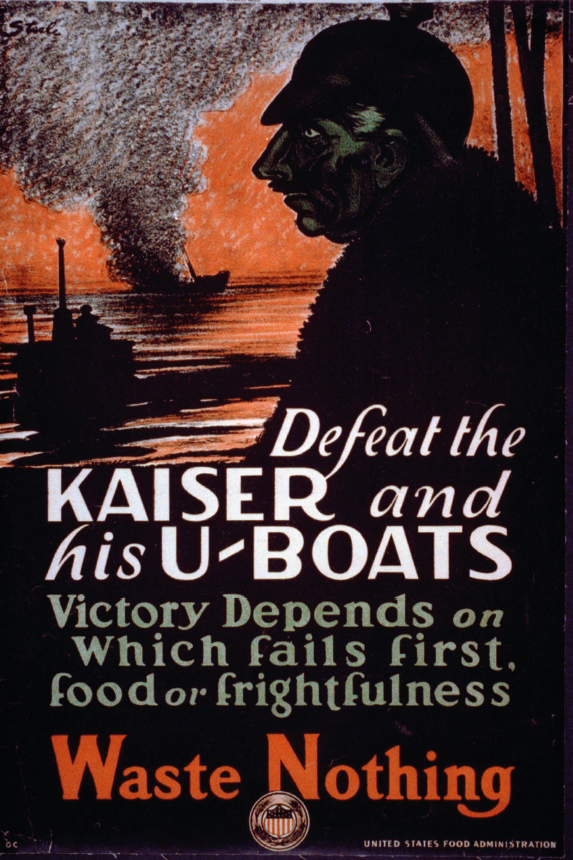

THE QUESTION OF adequate food supply was to become a major issue during the war.

Early on, with its naval dominance, the British established a blockade of the German ports, with British ships patrolling the North Sea and English Channel. The Royal Navy was intent on preventing imports of ‘contraband’ to Germany, which included foodstuffs. By 1915, imports had fallen by half and feeding the German people became increasingly difficult. The health of the nation declined, and Ersatz substitutes for staples increased, their nutritional levels much reduced. By the end of the war, some 700,000 civilians are known to have died through malnutrition and associated diseases in Germany.

With Britain so hopelessly dependent on imports (up to 60 per cent of its food stocks), it was vulnerable to attacks on its supply system. Yet early on in the Great War, food control was unheard of, and it was not until 1916 that there was a move towards some form of formal restrictions on consumption. At the outbreak of war, concerns over shortages among the middle and upper classes led to widespread hoarding. That other unholy act, ‘profiteering’, was also a major preoccupation of the newspapers, and the opportunity to make money from decreased supply was perhaps too much to miss for some retailers. Both actions were loudly condemned in the press, yet rationing was not to be enacted until 1917. Imperial Germany was intent on starving Britain into submission, with U-boats targeting any ship – neutral included – that might represent a lifeline for Britain in terms of food supply. Around 300,000 tons of shipping was sunk per month; in April 1917 alone, a record 550,000 tons of shipping was lost. This level of destruction meant that some foodstuffs were going to be in short supply.

Glasgow food poster (restored).

Food was not the only concern; housing was in crisis too. In Glasgow, with its tradition of tenement houses, families regularly squeezed into apartments with two rooms. With available tenements reduced due to the influx of munitions works, unscrupulous landlords increased rents dramatically. Militant women’s groups were raised, and there were rent strikes against profiteering private landlords. On 17 November 1915 the women of Glasgow rose up and marched through the streets to protest about rents, the rising prices and the hoarding of food. On the strength of the march, the Rents and Mortgage Interest (Rent Restriction) Act 1915 was introduced in order to rule out some of the worst practices. But ill-feeling still simmered. Our object is a poster, produced for just this one march by a local printer, which expresses the feeling of frustration by the women of Glasgow. It demands fairness and threatens violent action against those who sought to take more than their fair share – of food, in this case.

It was not until December 1916 that there was a specific government department – the Ministry of Food – to deal with such issues in Britain. Set up in the wake of concerns over profiteering and hoarding (rather than the bite being taken out of imports by the action of submarines), this body replaced the Cabinet Committee on Food Supplies that had been created early in the war to ensure that there were adequate supplies of the most important foodstuffs. Exports of food were prohibited, and a raft of subcommittees and commissions were charged with keeping prices down and ensuring supplies were adequate.

Bread was an important food reserve for much of the population – it was processed, already cooked and cheap. Attempts to increase the yield of wheat from British farms were reasonably successful, yet the supply of wheat from overseas meant that baking sufficient bread to meet demand was a challenging task. Appeals were made to ‘eat less bread’ in order to conserve stocks, with campaigns and propaganda to boot; but poorer families found this self-sacrifice to be a difficult task. In early May 1917 the king issued a royal proclamation: ‘We, being persuaded that the abstention from all unnecessary consumption of grain will furnish the surest and most effectual means of defeating the devices of Our enemies […] We do for this purpose more particularly exhort and charge all heads of households to reduce the consumption of bread in their respective families by at least one-fourth.’ For some families, this was easier said than done.

British ration books: rationing was introduced in 1915 in Germany, and 1918 in Britain.

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Date of manufacture: c. 1916

Location: Private collection

THE BRITISH MUNITIONS of War Act of August 1915 (that followed the ‘Shell scandal’ of early 1915) brought all munitions manufacturers under the control of the new Ministry of Munitions. By 1918, it managed directly 250 government factories and supervised 20,000 more. There was a bewildering array of types: National Filling Factories (NFF), National Projectiles Factories (NPF), National Shell Factories (NSF) and a whole host of industrial sites concerned with the myriad aspects of trench warfare. While just 500,000 shells were produced in 1914, in 1917 some 76 million were manufactured. In all, some 2.5 million men would work in munitions factories during the war – but this would be inadequate. New sources of labour would be required, and the government turned to the unions in order to implement what would be termed ‘dilution’ of the skilled workforce – the use of unskilled male labour, and women.

One of the phenomena of the war was the production of heraldic china mementos in the shape of tanks, ships, weapons, aircraft and a miscellany of other military subjects. Heraldic china was an output of pre-war Staffordshire, and was born from a desire of day-trippers to bring back souvenirs of their visits to the seaside. On the outbreak of war, the representation of military objects in china was a new and lucrative market, and there was no end to the ingenuity of the often fiercely competitive ‘crested china’ designers. The model illustrated is a representation of a female munitions worker, clad in simple working overalls and headgear, wearing her distinctive triangular badge and offering up an example of her output, with the words: ‘Shells and More Shells: Doing her bit.’ This model carries the crest of the huge munitions factory situated at Dornock, near Gretna, Scotland – so it may well have been the property of a ‘munitionette’, or perhaps was purchased for her family. Here, the huge National Filling Factory was constructed late in 1915, and was truly vast, stretching some 9 miles from Dornock to Longtown. The factory complex manufactured cordite – the principal propellent in munitions.

Munitions workers.

Prior to conscription, men had been encouraged to register as a ‘war munitions volunteer’, a status that exempted them from military service – at least in the short run – but required them to be mobile. Women war-work volunteers had been sought in March 1915, yet take-up of the volunteers by the factories was slow at first. Viewed with some suspicion by many male workers, agreement had to be reached between employers and unions – the first of which was attained in November 1914, followed by a variety of others leading up to the adoption of the Munitions of War Act in 1915. With this in place, further negotiations would follow to allow women to take on more and more work in what were traditionally ‘closed shops’.

With these moves, and with an increasing number of men being ‘combed out’ of war work in order to take their place on the front line, women would be called to the munitions factories as ‘munitionettes’ or as ‘Tommy’s sister’. With munitions including everything from the filling of shells through to the manufacture of boots, bandages and tents, there was a crying need for labour, and an estimated female workforce of 800,000 would be employed in all aspects of their creation, some 594,600 working under the aegis of the Ministry of Munitions in one role or another. Of these, the largest proportion, almost 250,000, would be engaged in the filling and manufacture of shells; the remainder would help create ordnance pieces, rifles, small arms ammunition; they would work with chemicals and on the myriad devices needed in trench warfare. In many cases, women would come to outnumber men in the factories. At Dornock there were some 11,576 women employed, almost 70 per cent of the workforce making cordite, nitroglycerine and other explosives.

Munitions work would be long and hard, but women were attracted to it for a variety of reasons, whether from patriotic duty or simply a desire to better their lives. They would also be reasonably well paid, typically £2 2s 4d per week; yet this was still half the amount that was paid to men – there would be a long way to go for equal treatment.

Country of origin: Canada (in United Kingdom)

Date of production: 1916

Location: Private collection

IN THE AFTERMATH of an attack many men would be stranded in no-man’s-land, sheltering in shell holes, waiting and hoping for the arrival of stretcher-bearers. Under the Hague Convention, stretcher-bearers were given non-combatant status so long as they wore an appropriate armband to identify them. In all armies, it was the duty of stretcher-bearers to search the battlefield for casualties. Regimental stretcher-bearers’ responsibilities usually ended at the regimental aid post; from here men would be dispatched to the rear areas and would be in the care of the army medical services, whose role it was to care for the wounded and to evacuate them efficiently from the front line to hospital and then home: heimat or ‘Blighty’.

Movement from the front was long, laborious and, for the wounded, painful. The chain was a long one: in the British Army, the first move would be to the regimental aid post, run by a doctor and a small number of orderlies, and which was set up close to the front line; next would be the advanced dressing station, set up at the farthest frontwards limit of wheeled transport, and run by the Field Ambulance, with three such units of men attached to an infantry division; from there the next move would be to the casualty clearing station, the first of the major hospitals and then, ultimately, to the base hospitals. At this point, doctors made the fateful decision whether or not to move the sick and wounded home. Similar chains existed in the other combatant nations.

Across the United Kingdom, as in Germany, war hospitals received soldiers ‘from the front’. In addition to military hospitals, many civilian premises were handed over to military use. Soldiers arriving from the continent by hospital trains were then dispatched across the country. They were then set up in large private houses, municipal buildings and other premises in order to satisfy the demand for suitable accommodation, often staffed by volunteer nurses. With the outbreak of war in 1914 there would be floods of volunteers in all combatant countries, not all of the volunteers being suited to medical work, and many of them with little or no experience. In Britain and Russia, the royal families led by example, with Princess Mary and the imperial grand-duchesses of Russia wearing the uniform of nurses.

It was a fashion of the day for nurses to keep albums that were used to record sentiments, poems, drawings and simple signatures penned by their patients. Many are poignant; the soldiers concerned could be patched up and sent back to the front line. Illustrated is a page from one nursing sister’s album from the Endsleigh Palace Hospital in Bloomsbury, central London. Lieutenant George Ansley Wallace of the 25th Battalion (Nova Scotia Rifles) Canadian Infantry, who served in France, recorded his appreciation: ‘They [sic] will ever be fond memories of our thoughtful sister’. The entry was written on 5 July 1916 – together with a Flanders poppy. His fondness went further: as a gift he gave his nurse a maple-leaf frame made from a shell case discarded on the field of battle. In most cases, hospitals in Britain were segregated according to rank. The Endsleigh Palace Hospital is typical. Originally a hotel, it was requisitioned by the War Office in 1915 and turned into a hospital for officers, equipped with 100 beds. Here, male medical orderlies also acted as ‘valets’ for the officers, with the nurses – a mixture of volunteers and trained staff – tending to their recovery.

Inside a war hospital.

Across Britain, some 38,000 Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) worked in hospitals – while others would serve overseas. VADs administered some 3,000 military auxiliary hospitals (created in a variety of settings, from grand houses to public buildings) and convalescent homes during the war. Some 10–15 per cent of soldiers mobilised were killed, but many more were wounded or taken prisoner, and it was relatively rare for a front line soldier to survive the war completely unscathed. Wounding was a common experience; most longed for the opportunity of gaining a minor wound that would take them back home. Not everyone would have the opportunity.

Wounded soldier in a British war hospital, recipient of the Military Medal.

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Date of issue: 1918

Location: Private collection

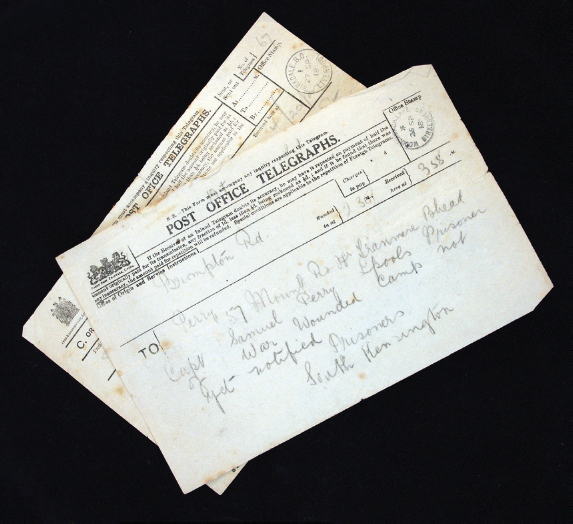

RECEIVING A TELEGRAM from the War Office was dreaded during the war; more often than not it would signify that a loved one had been killed, wounded or taken prisoner. Usually the preserve of the officer, ordinary soldiers would receive instead a standard letter with blanks filled in with the soldier’s details. Similar letters were sent by German authorities to their soldiers’ families. Sometimes, however, the first inklings of a casualty might be a letter returned home with the brutal and stark message ‘Killed in Action’ written or stamped as a cachet on its unopened cover; in other cases, letters would be written from the adjutant or chaplain to soften the blow. More often than not, these letters would profess that the soldier in question had not suffered, and had died instantly; the truth might be harder to bear. For example, in the case of Private Charles Chard of Somerset, serving with the Yorkshire Regiment, the colonel of his battalion was to write: ‘Pte Chard was killed in the Arras Sector in August 1917 while out on a daylight patrol “instantaneously”, he is buried in the Sunken Road Cemetery in Fampoux.’

Captain Perry of the 9th King’s (Liverpool Regiment) was one of the lucky ones. Captured in the German offensives of 1918, he spent the remainder of the war as a prisoner. One can only imagine what his family felt when they received a telegram from the War Office, and the fear that they must have felt as they opened the envelope. His family in Birkenhead was to receive two telegrams: one informing his family that he was missing; the other that he had been wounded but was a prisoner. The telegrams, stark in their brevity, at least brought news that he was safe. So many other telegrams would not.

For the British, some 10–15 per cent of those who joined up were killed, a figure comparable to the German Army. But it was the Scots who would lost twice as many men. The Scots were not the only group to lose heavily; with large numbers of middle-class men joining the colours in the early years, there was a disproportionate number who died, again almost one-quarter of them. Many would serve as officers, and officers would lose more in proportion than ordinary soldiers. This would be the ‘lost generation’ that would be much discussed in post-war years, the flower of British youth. For the next of kin of those who had given their lives in the war there would be a plaque that resembled an oversized penny – earning it the nickname of the ‘death’ or ‘dead-man’s’ penny – more than 1 million plaques were produced to commemorate those who died. Many more would be seriously wounded, maimed or psychologically damaged – for these men, re-adjusting to family life after the war would be a struggle.

Country of origin: United Kingdom (in France)

Date of construction: 1916 (replaced 1923)

Location: Gordon Dump Cemetery, Ovilliers, France

NOW THE COMMONWEALTH War Graves Commission, then the Imperial War Graves Commission, the CWGC has a history that dates back to the early part of the war, and to one man, Fabian Ware. At the outbreak of war, Ware was rejected for military service, but volunteered to command a mobile unit of the British Red Cross, which supplied motor ambulances to the battle front. With casualties mounting, it was obvious to Ware that the British had no effective means of maintaining a record of the battlefield graves of those soldiers who had died in action – and who had been buried by their comrades. With this important duty largely neglected, Ware set about collecting and marking the position of such burials, and in 1915 he was transferred to army control, leading the newly formed Graves Registration Commission (GRC). The GRC soon set about its task: by October 1915 it had recorded 31,000 graves; within eight months, 50,000. And with so many men posted as missing, and so many families wanting to see the graves of their loved ones while the war still raged, Fabian Ware’s GRC also acted to send out photographs of graves in an attempt to alleviate some of the suffering – 12,000 had been dispatched by 1917.

But simply recording the graves was not sufficient for Ware. He became increasingly concerned that the graves so recorded should be tended and maintained. With the support of the Prince of Wales, the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) came into being, established by Royal Charter on 21 May 1917. The IWGC faced tough choices: from its outset there would be no repatriation of the dead, there would be no distinction based on rank, and the grave markers would be uniform. There was opposition from some quarters, but the questions were finally settled: the IWGC would ensure that the sacrifice of the men and women who had served would be remembered in perpetuity.

At first, graves were marked with simple wooden crosses. That for Lance Corporal Kettlewell of the 10th Battalion West Riding regiment is typical. Killed in action on the Somme on 28 July 1916, his simple grave marker was placed in Gordon Dump Cemetery, near Ovillers on the Somme. Weather-beaten and worn, the cross was returned to his family when the IWGC commenced their long job of replacing the crosses with headstones. In France and Flanders this was a momentous task; replacing the crosses demanded 4,000 stones per week to be sent from Britain in 1923; just four years later, 500 cemeteries had been completed and 400,000 headstones were in place. Admired the world over as havens of peace and tranquillity, Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries are maintained to the highest standards; fitting tribute to the men and women who lost their lives – and to the vision of one man, Sir Fabian Ware.

Country of origin: France

Date of manufacture: c. 1918

Location: Historial de la Grande Guerre, Péronne, France

THE VAST MAJORITY of wounds suffered by soldiers in the Great War were caused by artillery fire – some estimates place the figure at 70 per cent. The scale of devastation wrought by the lethal shards of metal from artillery shells is staggering. Protection for the fragile body of the average soldier was limited; the very fact that the war had developed into parallel lines of trenches, with men garrisoned in dugouts that got progressively deeper, demonstrates the need to escape the destructive power of the artillery shell. In 1915–16, the arrival of steel helmets on the battlefield improved protection for the head, but in most cases, helmets were only proof against small fragments such as shrapnel balls and spent bullets. Both the Germans and the Italians produced heavy steel armour to protect their sentries, and some companies entered the marketplace, producing such items as the Dayfield Body Shield. But most cases, soldiers were simply caught unprotected in the ‘storm of steel’.

The figures for the wounded are stark. For both the British and German armies, some 25–30 per cent of those who served were wounded, with the wounds created by the explosion of steel artillery shells being the most traumatic. Amputation was the only option, yet surviving the operation – in the days before penicillin – depended on the soldier’s fitness and a good deal of chance. With shrapnel and shell shards carrying the dirt of the trenches into the soldiers’ bodies, the possibility of gangrene was high – particularly when men had to wait for an operation while still in the battle zone. In the British Army alone, some 41,000 men lost a limb: 69 per cent of them a single leg, 28 per cent an arm and the remainder double amputees. For the Germans, there were almost twice as many, some 74,620 amputees; of these, 21 per cent lost one or both arms and 32 per cent one or both legs, while the remaining 47 per cent had partial limb loss.

The provision of prosthetic limbs for disabled soldiers was a task that was not taken lightly. While newspapers and subscriptions to patriotic magazines such as John Bull provided insurance schemes for soldiers that would pay out £50 for the loss of a limb, £100 for two, this would be little consolation for men who might not be able to work. Limbs were expensive to make and fit; wooden ones were the cheapest, with lighter aluminium ones being preferred. Images from British war hospitals in 1916 show cheery soldiers trying out their new limbs while still in hospital. Our example is a sophisticated leather-and-aluminium creation that was intended to give functionality and was designed to mimic the missing hand as closely as possible. Yet, despite its sophistication, many men preferred simple hooks – perhaps because they were easier to handle or more robust.

Those mutilated were only too evident across Europe; the scar left by the war was deep and its effects lasting. The images of amputees begging in the streets of Europe in the harsh economic climate of the 1920s are enduring in their poignancy.

Austrian poster promoting the employment of mutilated men.

Country of origin: United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Italy, USA

Date of manufacture: 1919

Location: Private collection

THE VICTORY MEDAL was one of the many that were issued to all Allied nations. British, French, Belgian, Italian and US versions are illustrated; there are many more. The idea of a common victory medal, similar in design, came about in 1916, when the Allies together discussed the possibilities of victory.

The details of the scheme were drawn up by a committee formed by the British war cabinet, chaired by Sir Frederick Ponsonby, with representatives from every relevant government department in order to consider the question. Their findings were clear:

In wars in which European countries had been allied together, it has been the practice for the Allies to exchange a certain number of war medals, e.g., the Crimean War and the Boxer Rebellion. This was a comparatively easy matter when the forces were not so numerous, but in the present war, where armies are composed of millions, it would be practically impossible to distribute with any fairness a certain number of war medals from each ally. It would, moreover, be extremely unfair on the troops who had fought in theatres of war outside Europe, since they would probably be excluded from this distribution.

From these deliberations came the formulation of a policy that would help direct Allied thoughts. The Victory Medal was born from these discussions and came about from the meeting of the representatives of all the Allied powers in Paris in March 1919. At this meeting, it was agreed that an Allied war medal would be produced that would be called the ‘Victory Medal’. The simple principle behind this was that it was the one name that the countries of the former Central Powers could not claim for a decoration. It was agreed that the medal should be 36mm in diameter and would bear an identical ribbon of watered silk that comprised two rainbows joined by red in the centre. As the committee wished to issue the medal as soon as possible, it was also decided that, with time short, each country should apply its own design. However, central to this should be an allegorical figure of Victory on the obverse, while on the reverse there would be the inscription: ‘The Great War for Civilisation.’ Victory was to have been represented as a female winged figure; this held true for all excepting Siam and Japan, which adopted figures relevant to their cultural traditions.

In the end, Belgium, Brazil, Cuba, the new nation of Czechoslovakia, France, Greece, Italy, Japan, the newly independent nation of Poland, Portugal, Romania, Siam, the Union of South Africa, the United Kingdom and its empire and the United States all issued their own medals. The greatest number of medals issued was by Britain: some 6,334,522 medals to men and women from across the empire (though South Africa issued its own, bilingual, version). The United States (2.5 million) and France and Italy (both 2 million) come next, with the other nations issuing the medals in the thousands. An upper estimate of awarded medals might be some 14.6 million.

Country of origin: France

Date of manufacture: c. 1927

Location: Private collection

THE IDEA THAT the soil of France was sacred dates back centuries. With two German invasions within fifty years – during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 and the Great War in 1914 – France had suffered the marching boots of enemy soldiers all too often.

For one man, the sculptor Gaston Deblaize, the very soil of the battlefields of France, where the poilus had lived and died in the defence of their country, had great significance. Deblaize was a former soldier and served for forty months at the front with the 356th Regiment of Infantry. He served at Verdun, in the Tunnel des Tavannes, and was awarded both the Médaille Militaire and Croix de Guerre for his bravery. Gaston as an artist was inspired by the earth itself and by the simplicity of the soil, by the wheat that grew in the rich arable lands of France and by the comradeship of his friends. Drawing on these concepts, Deblaize developed the idea of a ceramic container that would contain the sacred soil taken from the battlefield at Verdun, acting as a monument to his dead comrades. With that ground so heavily fought over, these works had great significance.

The example illustrated is typical. It is based on the way-marker stones (‘borne’) that Deblaize happened across during his years of marching along the roads of France as a soldier. It is topped with the Adrian helmet, that symbol of the poilu; again, this reflected times when the artist had placed his own helmet on the wayside markers. Marked with the dates 1914 and 1918, it carries the immortal name ‘Verdun’, with the phrase ‘Cette borne renferme une parcelle de terre sacrée de Verdun’ (This marker contains a piece of the sacred ground of Verdun). The concept grew and the markers sold: ‘In memory of the dead of the Great War – of the Mutilated – of Veterans’ under the patronage of l’Association des Gueules Cassées (the Association of ‘Broken Faces’), remembering those men who had been horribly disfigured by the brutality of the Great War. The first to be made was presented to the president of the republic; it contained soil from the ‘trench of the bayonets’ from Verdun – a trench that contained the bodies of men permanently entombed by a collapse.

Symbolic of the link between the dead, the mutilated and the earth of France, the project was expanded to other parts of the battlefront: to Alsace, Champagne, the Somme and Yser. Mindful of the sacrifice of the soldiers for the sacred soil of France, Gaston Deblaize went on to extend his project to the construction of seven large-scale ‘bornes’, each containing ceramic containers of the soil of the battlefields. And at each harvest time, the wheat ripened, it is laid at the foot of each one, a remembrance of the capability of the land for rebirth.

Country of origin: United Kingdom (in Belgium)

Date of construction: 1927

Location: Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial, Ieper, Belgium

THERE ARE MANY memorials to the dead. In London, the Cenotaph is the national place of mourning, the impressive stone ‘empty tomb’ that sits in Whitehall. Raised as a temporary structure for Armistice Day 1919, it was reconstructed in stone for the same day in 1920 and has been the focal point for British mourning ever since, matched by equivalent structures across the British Commonwealth. In France, national commemoration is focused at the Arc de Triomphe, where from 1920 was interred the Unknown Soldier: ‘Ici repose un soldat Français mort pour la Patrie 1914–1918.’ Across Britain, France and the other Allied nations, local memorials sprang up that sought to remember the sacrifice of their men and women in war. In Germany, memorialisation was more difficult. While some local memorials did spring up, the last large national monuments were those constructed in the late nineteenth century, particularly the Kyffhäuserdenkmal in Thuringia that commemorates the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm I. With no large monuments constructed in the aftermath of the Great War, German veterans sought out these relics of their imperial past as a point of meaning.

On the battlefields of France and Flanders, the war cemeteries remained the ultimate memorial to the ‘lost generation’. For France and Germany, smaller cemeteries were combined to make visually impressive statements of loss; for France, there was the need to cleanse the soil and return it to agriculture. Here, the use of ossuaries and huge ‘national cemeteries’ was the norm. For the Germans, concentration of their soldiers’ graves into large cemeteries was required by their former enemies, there was no debate. For the British, it was different again. Small battlefield cemeteries, immaculately kept, dot the landscape and permit the reconstruction of battle lines on the ground; larger cemeteries were formed to free the soil for cultivation but also to take the bodies of those men recovered from the battlefields after the war.

The Menin Gate is one of many memorials on the Western Front that commemorate the missing, those men who fell and who have no known grave. Designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield, it took four years to build and was constructed on the site of one of the gates in the Vauban fortifications that surround the city of Ypres – and which, in part, protected it during the war. Through the gate passed the British armies on their way to the front, along the straight road that gradually rises from the clay plain of Flanders to the low hills that surround the city. The gate lists the names of 54,393 men of the British and Commonwealth armies who fell in the Ypres Salient during the war. There are other monuments of similar scale in France: the Notre Dame de Lorette, the Douaumont Ossuary and the monumental Thiepval Memorial on the Somme. But there is one thing that makes this memorial unique: here, on every night since its inauguration (excepting the years of Nazi occupation), buglers from the city’s fire brigade sound the last post in memory of the soldiers who died in the war – ‘At the going down of the sun, and in the morning, we will remember them.’