Chapter 5

My Mother, Yee Dong Sing Dere

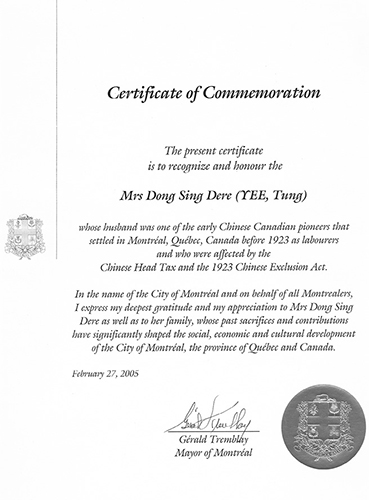

“I express my deepest gratitude and my appreciation to Mrs. Dong Sing Dere as well as her family whose past sacrifices and contributions have significantly shaped the social, economic and cultural development of the City of Montréal, the province of Québec and Canada.”

Yee Dong Sing was born in October 1905 in Shui Ben Hang, Toishan. She had two siblings. When she was young, her older brother left his young family at home and went to the Philippines to seek his fortune. He was later killed when the Japanese bombed Manila. My mother and her younger sister, Shao Chun, were left in the village to look after their parents. At that time, few girls attended school, but Dong Sing was a good learner, so her aunt, a teacher, taught her at home. When Dong Sing was nineteen, her mother told her that an auspicious marriage had been arranged for her with a Gim Shan Haak, a Gold Mountain Guest.

Would she have thought it auspicious if she had read a poem like this, I wonder:

Right after we were wed, Husband, you set

out on a journey.

How was I to tell you how I felt?

Wandering around a foreign country, when

will you ever come home?

You are wasting many joyous years of our

precious youth.

My spring heart has turned to ashes.

Poverty does not allow me the luxury of a choice.

But let it be known to all my sisters:

Don’t ever marry a young man going overseas!

Dong Sing left the Yee clan and entered the Dere clan in 1925. “At that time, I wanted to go to Canada,” she told me. “I asked your father to ask about bringing me to Canada. But he said the government did not allow it. He had to leave after a year and a half.” My father returned to the village three other times after they were married. By 1935, Mother was left at home to raise four young children and to look after the household including her mother-in-law.

Decades passed.

One of my earliest memories is of my mother and I leaving our ancestral village to go to Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong province, to stay with my second sister. She had recently married and was living there with her husband, also from a head tax family. It must have been 1951. It was early morning with a misty breeze blowing across my face as we walked out of the village past the old banyan tree that guarded the entrance. The last image as I turned my head for one last look was the “mountain”—a low hill that I climbed as a toddler. We walked to take a small boat to cross the Tanjiang River, one of the tributaries flowing into the Pearl River Delta. I recall sitting at the bottom of the wooden boat and seeing the water skimming by. The boat was controlled by a man at the rear providing both motion and direction with the to and fro movements of his paddle. On the other side of the river, we took a bus to the city. In those days, there were no bridges crossing the river; today, there are modern highways taking people from Toishan to Guangzhou.

In China, it was traditional at the time for parents to find decent men with proper families for their daughters to marry. On his last trip back to China in 1947, my father thought long and hard about this.

Pui King, my eldest sister, would end up getting married later that year. My father had met her future father-in-law on the ship back to China; the two men spent the month-long voyage planning the marriage for the number one son and the number one daughter. But when my father broke the news to my sister, she was shocked. She was in her last year of high school and hadn’t thought about marriage. “Marriage is an affair arranged by the old people, it was none of my business,” she told me much later.

When the prospective mother-in-law came to visit our family, Pui King refused to see her. “How can I allow my son to marry a girl that I’ve never seen?” Madame Fong persisted.

My mother was not enthusiastic about the marriage since Pui King was still in school and only seventeen, but people in the village encouraged her. “You have three daughters, times are hard. Give your eldest daughter an opportunity to go to Gim Shan.” Mother agreed but acquiesced to her daughter’s rebellion at not letting her future mother-in-law see her before the marriage. “If this is a blind marriage, then let them be blind,” Pui King insisted. So the battle of wills between the future mother-in-law and daughter-in-law began.

My mother compromised and allowed the mother-in-law to see her second daughter. King Sin was only fourteen. “They both look the same,” Mother said reassuringly. The mother-in-law approved when she saw King Sin, accepting my mother’s assurance that the older sister was as beautiful as the younger one.

It was a festive, boisterous affair with palanquins carrying the bridal party and the parents. Pui King was allowed to finish high school after the marriage and she had her first child shortly after. It was a marriage made in heaven. As I write this, my sister has been married to the same Gim Shan Haak for seventy years.

Marriage for my mother, of course, had meant becoming a “Gold Mountain Widow,” as she described herself. She told me late in her life76 that she always used to hope my father would come back safely and have a smooth journey. “I took care of the children and planted vegetables, grew rice to support life in China. When the kids grew up, they could go to school and it needed money.”

My mother asked my father to send back more money, but understood he could only make a little money out of working in the laundry. “Life was hard for him. He took good care of the family and sent back money even though he made little. Some village relatives had some fields but they did not have money. So, I used $400 [money sent by Father over the years] to buy the land, about 3 mou [half an acre]. The harvest provided us with half a year’s food. At that time, I had three daughters and one son.

“Your father could not return because of the Japanese invasion. [Japanese troops began occupying Guangdong in 1938.] With four children we needed a lot of food; life was fine if we have the land to grow food.

“Meanwhile, Father sent back some money. Your uncle [my father’s older brother] was the village head and he smoked opium. He took all the money Father sent, even when I was sick. During the Japanese war, we suffered and my health wasn’t good. I got sick when I didn’t have proper meals. I was sick for many months in 1944–45. There was no money from Father because of the Japanese. Luckily, I recovered with help from my neighbours. I ate the bad food and saved the good rice to cook rice soup for the children. We did not have rice to eat for months—until the harvest.”

My mother recalled the women in the village being close, “like sisters,” and sharing what they had. “It was mostly women left in the village with our children. We all knew that life was hard for our husbands in Canada. When we sat together, we would talk about whether they had sent money and some of them would say they received money.

“Father knew it was hard in the village and he felt sorry for me,” she told me. “When the war was over, Father sent back money immediately—a few thousand Chinese dollars—to Toicheng,77 where his brother operated a publishing company.” With rampant inflation, such an amount would not have been large. But my uncle took it all.

“Since I had no money, I had to borrow money from my relatives,” my mother said. “I told them that I would give them back the money when Father sent some. Life was hard. When I asked my brother-in-law to give me back the money, he didn’t. He did not even tell me that he received the money. Father sent me a letter asking if I have received it. I asked brother-in-law to give me the money, he told me he had spent it all. So, there was nothing I can do.”

With the defeat of the Japanese in September 1945, Toishan was still in turmoil. There were natural and man-made disasters. A typhoon tore through Toishan in 1946, leaving many dead and devastating the fields. The KMT government drove the local economy to bankruptcy. Mother was desperate to join Father in Canada.

“When I received money at the time, it was okay,” she said. “But when I didn’t, life was very difficult. I was very worried. I had four children. To raise them I had to worry about the school fees, the clothing, the expenses, and I was lonely at the time to think about all these problems by myself.”

When it came to power with the Liberation of China in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party developed a policy to collectivize the land. Our family had purchased some land in the village with money my grandfather and father sent back over the years. The family was categorized as landlord class since my mother had hired someone to work the field, which consisted of two plots, about half an acre altogether.

“During Liberation, my second daughter didn’t get married yet. And my youngest daughter was very bright. I sent her to Guangzhou to study and we stayed there. When the Communists came, we had to go back to the village. You were very little then, I had to carry you on my back. I was almost crazy with fear, and constantly crying in the streets.

“I was so scared and I cried a lot because the Communists have to make you work and I was so miserable at the time. The District Leader was very kind to me and explained what will happen, but I was afraid. He explained why they took the land.” He explained the Communist concept of the collectivization of land for the greater good but Mother didn’t understand.

After the war, my father wanted to sponsor my mother to come to Canada. It was only with the rescinding of the Chinese Exclusion Act that my father was able to obtain his citizenship in 1950, after twenty-nine years without civil rights in his adopted country. He had begun planning to reunite his family in Canada, and he brought my older brother, Ging Tung, to Canada first to join him and work in Grandfather’s laundry; then he worked to bring my mother and me. Ging Tung left China in 1950. After sending my brother off in Hong Kong, my mother and I returned to the village because she was worried about my three sisters.

“Your father wrote that we should join him. Your brother had already left and now it was our turn to go. I thought, life is difficult here; maybe it’ll be better in Canada.

“Those years at home were very difficult. No money was getting through since it had been sent to Hong Kong. Brother-in-law was already there and he kept the money.

“I wanted to go to Canada to be with your father. But even if I wanted to, I couldn’t. That’s why it made me so miserable. We were using all kinds of methods to come to Canada. Your second sister had married and we decided to go to Guangzhou to stay with her husband’s family. We stayed in Guangzhou for two years, and then we went to Hong Kong. This was about 1953.

“In Hong Kong we stayed with my eldest daughter’s family on Portland Street. She had already reached Hong Kong. My second daughter joined us the same year. My third daughter didn’t want to leave China. Her head was full of communist songs. But later, I persuaded her to come because we needed to keep the family together. On Portland Street, we had four households living together. The house was full of young children. You played with your little nephews and nieces. I wanted to come to Canada and experience how life was elsewhere. I wanted to be together with the family here but your brother didn’t want me to come. He wrote that it would be too cold and too difficult for me.”

In 1956, my mother received the letter saying that she had been approved to come to Canada.

“I felt so happy and relieved,” she said. She would be travelling with me and she knew it was a long distance, but she felt certain that life in Gold Mountain must be better than life in Hong Kong.

“You were about seven,” she told me. “We went to the Immigration office and you even showed me how to get there and how to use the elevator. We were very happy because you were going to see your father soon.”

Mother broke the news that changed my life forever. “Ah Wee,” she said, “you are not going to school today. Tomorrow, we are going to Gim Shan to be with Baba.” Even though she had prepared me months earlier that we would be going to Canada, it still came as a surprise when the actual day arrived. This was April 1956.

Father booked passage for us on the SS President Wilson. The fare for an economy class cabin was $345 per person, but I don’t know if he got a reduced fare for a child. The ship left Hong Kong for San Francisco in early April 1956. My mother made friends with the woman in the next cabin. She was travelling to Boston with her six-year-old daughter to join her husband who operated a hand laundry there. I remember Mother being seasick. The little girl and I went to the cafeteria to get some jook (rice porridge) for her.

At the pier in San Francisco, a Chinese agent met the Vancouver-bound passengers. He took us to a Chinese restaurant for dinner and put us on an overnight bus to Vancouver. Third Uncle78 met us in Vancouver and brought us to the train station for the trans-Canada trip to Montreal.

Mother reminisced about the trip, “Do you still remember Third Uncle? He was very kind to us. He bought you some playing cards for the train when you were seven. I saw him again in 1971 when we went to Vancouver. He passed away a few years ago.”

My mother’s experience was similar to that of other Gold Mountain widows. My parents were young enough to create a new life together in Canada. However, others were in their sixties or even seventies and those women came to nurse the elderly husbands they hardly knew. Some complained that life in China was easier than in Gim Shan.

Recalling her early days in Montreal, my mother said: “Remember? Your father picked us up in a taxi and right away, we went to the laundry. We did business in the laundry and we lived in the laundry. At that time, I only went out on Sundays and sometimes I saw some friends. They said, ‘You should rent some place to live instead of staying in the laundry.’ Your father lived in the laundry all his life and he was too cheap to pay rent for another place.

“The day after we arrived, I started to help your father in the laundry, ironing clothes. It was very hard work, the iron weighed eight or ten pounds, and the weather was very cold. When I first came, I didn’t know any English. I just hid in the laundry; I didn’t go anywhere. Your father taught me some English when we were ironing—the days of the week, numbers and a few phrases to take the bus to visit friends.”

After working for about two years and realizing they weren’t making enough money, she thought about the fact that some of her children were in Montreal too and that she didn’t have a house for them. So my mother exerted her independence by working outside the laundry, despite Father’s objections.

“I went out and met with Mr. Chang and asked him if he could find me a job,” she recalled. “After about two weeks, I met him again, and he said that a hat factory needed people and asked me if I wanted to work in a factory. So, I went to Chinatown to meet him. I went with another lady to work in the hat factory. There were about five or six Chinese women who worked there. I made friends with the Chinese women. Their husbands had laundries and gambled away their money. That is why they had to work.”

She left my father alone at home to iron clothes. “He complained that I didn’t need to work in the factory. It was harder for me, not for him. But I said if I stayed at home, I couldn’t make enough money. … I was thinking about the future and my children. I wanted to give them a house to live in. The only way was to work outside the laundry.”

Apparently my father thought differently. He believed that as long as we had enough to eat, it was okay.

“He complained that I was not helping him,” my mother said. “But I was. I finished work at four and got home at five or six. As soon as I got home, I plugged in the iron and started ironing clothes, bed sheets, pillowcases and other things until seven or eight. Then I had to cook dinner. It was worse on wash nights; sometimes we had to work until two in the morning to finish washing all the clothes. I was so tired the next morning when I went to the factory. I really felt bad at the time. I wanted more for the future.

“I saved all my money, about $5,000 and after a few more years, $10,000. Your brother also saved some money so we bought the house on Second Avenue with a loan from the family association woi. It cost $20,000 and we paid it off in two to three years.” The house was typical of Verdun at the time and “had six numbers,” in my mother’s words (it was a six-plex). So, she said, “we collected some rent to pay the expenses.”

When her children had their own lives and their own homes, she sold the house.

Like my mother, many of the women that came to Canada at the time did triple duty as wife, mother and worker in the laundry, restaurant or factory. Many were isolated, lonely and dependent on their husbands. None of them had any language skills in English or French, so they were grateful for whatever money they made outside their husband’s laundry. Like my mother, many were ambitious for the future of their family and their children. My mother was a strong and capable woman and she was the force that held our family together. She worked hard to get Father to sponsor other members of the family to Canada. There was my third sister, my mother’s younger sister and husband, and several of her nephews and nieces.

“I worked in the laundry for seventeen years,” my mother said. “I had gallstones and I was always in pain. In 1968 I had the operation to remove my gall bladder and I felt better. In the winter, the weather was cold. I did the ironing and the draft from the cracks in the wall made my legs cold. My legs were bleeding from being so chapped. My hands were sore with calluses from holding the heavy iron.79 I had no choice but to go outside to work. At the time we were trying to get your aunt, my sister, over from China. So we needed to have some money in the bank. I gave the money to your father to put in the bank. He didn’t take any of my money and he never asked for any.”

She met “some Western ladies” in the laundry. “There was one woman who always greeted me with ‘How are you?’ and I also greeted her with ‘How are you?’ She invited me to her house once. It was on our street. She had three rooms and a lot of stuff on the balcony. There were other ladies who were kind to me. When I had my operation they asked about me.

“It’s not good to complain, people will look down on you. It’s better to say good things than bad things. But your father was grumpy with me. He was very kind when he was in Toishan—here, he was different. He didn’t care about anything but the laundry. He just worked from day to day but I never held that against him.”

My father took care of the shopping, she added, going to Chinatown every Sunday to buy the rice and vegetables. “Sometimes, he would treat us to roast pork or char siu. However difficult it was, we worked together for the family. Everything is good now.”

Still, my mother said, “I like Canadian people [meaning whites], but equality is not really equality; it’s still for them, sometimes depending on the situation, it’s still to their advantage, right? It’s not very fair, but it’s a lot better than before. In the past people had to endure a lot, a lot of suffering. Now life is considered better. It is better now.”

After Father’s death in 1982, Mother went to Edmonton to live with my second sister, King Sin, and her two sons. King Sin’s husband had died a few years earlier. After a year, Mother returned to Montreal and got a subsidized apartment operated by the Chinese Catholic Mission on St. Urbain Street. For the first time in her adult life, she was not responsible for anyone but herself. The convenience of living in Chinatown allowed her to communicate in her own language. She did her own banking, took care of the rent, shopped and cooked her own meals. She found peace and serenity in her retirement years. In the apartment building there were many elderly widows who lived similar lives. She quickly made a wide circle of friends—a sisterhood—and organized mah jong groups with them. They talked about their children and grandchildren and how well they were doing.

Mother attended the same Chinese Presbyterian church where James Wing, my father’s YMCI friend, was an elder. The church or the old age club would take them for outings and organize elaborate Chinese New Year celebrations. My mother attended the church for the social companionship. But it was an old, worn, dog-eared copy of the Tao Te Ching that she brought from China and kept throughout her lifetime that inspired her life philosophy of balance and harmony. Mother practised this balance in her cooking where she tried to maintain the body’s equilibrium of yin and yang. This entailed making bitter broths made with ginseng and other herbs, which I was forced to consume as a kid.

She achieved contentment in her later years. In 1995, she talked about being happy that her children all had families. “You married a wonderful wife and have two bright children,” she told me.

“My heart is content. The government gives me a pension, about $1,000. I don’t need any money. The rent is $200. I buy some materials and make my own clothes and knit scarves and sweaters for my grandchildren. You and your brother and sisters visit me every week, sometimes twice a week. You bring me food, sometimes too much food for me to eat, so I share it with the neighbours. Some don’t have children to visit them. I don’t worry now. I feel calm, on lock.”80

Mother lived in her apartment until 1998. When she wasn’t able to cook for herself any longer, she moved in with my family. She enjoyed her time with a young grandson—Jordan was five when she moved in—and a daughter-in-law who dutifully and patiently listened to her tales of village life from so many years ago. We celebrated her one hundredth birthday in October 2005, attended by her five children, twenty-one grandchildren, seventeen great-grandchildren, and one great-great-grandchild. They came from around the world. With other relatives and friends, altogether over one hundred people celebrated her birthday.

In February 2005, Yee Dong Sing Dere was recognized by the City of Montreal with a Certificate of Commemoration presented by the mayor, who expressed his gratitude to my mother and our family for “past sacrifices and contributions” to Montreal, Quebec and Canada. My daughter, Jessica, received the award on behalf of her grandmother. The certificate could not make up for my parents’ pain and suffering caused by the racist and hateful laws, but it did recognize their history and contributions to Montreal.

In 2006, two days before Prime Minister Stephen Harper made his apology in Parliament for the Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act, Mother suffered a stroke. I informed her at the hospital of the apology. Even though she was paralyzed on the right side of her body, she smiled and said, “I am happy. You worked hard for this.”

On July 13, 2006, Yee Dong Sing passed away in her 101st year. She lived her first fifty years in China and her second fifty years in Canada. She was a true Chinese Canadian.

As much as I admire my father, my admiration for how my mother lived her life is more profound. She was a woman warrior, determined to succeed despite all the obstacles. She was caring with an overwhelming love; she wore her emotions on her sleeve. Her effect on me is immeasurable.