Jerusalem may not have been radical Islam's highest priority, but militant Islamic movements like the Taliban and al-Qaeda were nonetheless influencing the Middle East in ways that would have enormous implications for the future of the Holy City Beginning in the late 1990s a wave of unprecedented acts of religious intolerance, chiefly expressed through violent attacks on holy sites, appeared to be sweeping over a large area from Morocco out to Pakistan. It was as though an evil wind was blowing across the Middle East. Leaving a trail of desecrated and even decimated places of worship in its wake.

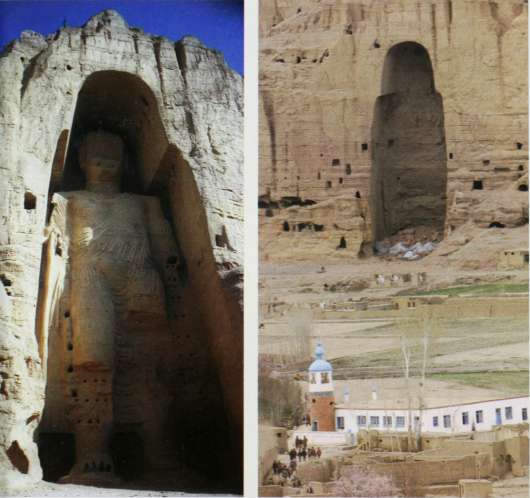

The most blatant example of this new wave, which captured headlines worldwide, occurred in early 1998 when the Taliban captured the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan, where two huge sandstone statues were located that depicted the Buddha. They were the largest Buddhist statues in the world, with one reaching a height of 165 feet and the other stretching 114 feet. They were also over 1.500 years old. : ~ The Taliban made multiple efforts to destroy the statues. In July 1998, Taliban fighter aircraft bombed the sandstone mountain in which the statues were located. Later in September. Taliban forces blew off the head of one of the Buddhas with explosives and fired rockets at the groin area of the other. The statues were damaged but remained standing.

The Taliban became determined to completely eliminate the ancient statues, despite growing international efforts to protect them. On February

26, 2001, Taliban leader Mullah Mohammad Omar ordered the final destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas "based on the verdict of Islamic scholars and the decision of the Supreme Court of the Islamic Emirate [of Afghanistan]." Secretary-General Kofi Annan interceded with the Taliban foreign minister to try to save the Buddhas. Neither the protests of the UN nor the international community, however, could stop them. A Taliban force came to Bamiyan from Kabul with a truckload of dynamite. Soldiers drilled holes in the torsos of the two statues, placed the dynamite charges inside, and detonated them, completely obliterating the Buddhas and reducing them to rubble. The entire operation was supervised by the Taliban defense minister. 15 And this was only the tip of the iceberg when it came to Taliban intolerance. Bamiyan was an area where the Hazaras resided; they were ethnically close to the Mongols and, more important for the Taliban, they were Shiite Muslims. The Taliban, who were militant Sunnis, tried to starve out 300,000 Hazara Shiites in Bamiyan; they managed to kill 5,000.

The assault on the Buddhist statues and the attempted mass murder of the Shiites was relatively new for Afghanistan, which did not have a long history of this kind of Islamic extremism. 16 Islamic armies from different dynasties had moved across Afghanistan since the seventh century. But no previous conqueror of Afghanistan had tried to eliminate the Buddhist statues. Was this a local phenomenon or part of a wider change in the Islamic world? As one writer noted, Islam had coexisted with pagan objects in the past, from the Sphinx in Egypt to the statues in Iranian Persepolis. 17 Why was this happening now?

The Taliban's religious traditions came out of the Deobandi Islamic schools of nineteenth-century India, which were not particularly extreme. What appeared to have radicalized the Taliban movement was an external source: the influence of Wahhabi Islam from Saudi Arabia on the ideological development of the Taliban leadership. After all, it was the Saudi religious leadership, the ulama, who advocated a Saudi relationship with the Taliban—this was especially true of Saudi Arabia's grand mufti in the 1990s, Sheikh Abd al-Aziz bin Baz, and the Saudi minister of justice Muhammad binjubair. Huge amounts of Saudi aid poured into the coun-

try, particularly from the large Islamic charities controlled by the ulama. 18 Jubair was known as "the exporter of the Wahhabi creed in the Muslim world." Finally, Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda also served as important conduits of militant Wahhabism to the Taliban so that in time his world-view permeated senior levels of the Afghan leadership. 19

The effects of Saudi influence became quickly apparent. There is little doubt that the financial dependence of the Taliban on Saudi Arabia and its clerics contributed to the formation of its religious and ideological outlook. The Taliban copied Wahhabi religious practices, even though when it came to the main four schools of Islamic law the Afghans traditionally had been followers of the Hanafi school, as opposed to the Hanbali school of law that was predominant among the Saudi Wahhabis. Despite these differences, the Taliban introduced religious police into Afghanistan that were modeled on the Saudi variety. Indeed, it is extremely likely that the new sectarianism that caused the Taliban Sunnis to attack Afghan Shiites also had Saudi origins.

For example, zfatwa, or religious opinion, signed by four members of the permanent committee of the Saudi ulama, including Sheikh bin Baz, asserted that the Shiites were not Muslims, but rather were to be defined as infidels. 20 Worse still was a fatwa issued in September 1991 by a member of the Saudi Council of Higher Ulama, Sheikh ibn Jibrin, arguing that Shiites were rafida —a term of opprobrium that can mean "disloyal" or even "apostate." According to ibn Jibrin, given that definition, killing them was not a sin. 21 Anti-Shiite doctrines had been part of Wahhabi Islam since the time of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab in the eighteenth century. But now those doctrines had the backing of the religious establishment of a modern Saudi state that was awash with petro-dollars, and were consequently being exported to the Saudis' Afghan client.

In order to attack religious sites that had existed undisturbed for hundreds of years like the Bamiyan Buddhist statues, the Taliban needed to internalize two messages from their Wahhabi mentors. First, they needed to see other religions—including Shiite Islam—in categories that no longer merited the protective status that Islam traditionally had granted to many groups during the various Islamic empires of the past.

This transformation was in fact occurring in Wahhabi Islam in Saudi Arabia. For the radical clerics there, Christians and Jews were no longer the "people of the book," deserving security within some second-class status, but were being called infidels. In fact, one Saudi cleric used this new demoted status for Christians and Jews to justify the use of weapons of mass destruction against them. Buddhists, or more precisely their ancient places of pilgrimage, did not have any basis for obtaining any better status than Christians and Jews.

Second, there needed to be a special religious sanction to destroy the religious sites that belonged to other faiths, especially after their status had been demoted. The Wahhabism exported by Saudi Arabia was rooted in an uncompromising campaign against shirk —any action that could be interpreted as polytheisitic, like saint or martyr worship that was frequently practiced by many religions around the tombs of holy figures. The Wahhabis particularly condemned those who petitioned these revered individuals to intervene on their behalf with God; in fact, a Muslim was not even supposed to mention the name of Muhammad in the opening of prayer, or to commemorate his birthday. In the eighteenth century, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab demolished the tombs of the companions of Muhammad, which had become objects of religious veneration.

The implementation of his doctrine reached the point that when Wahhabi armies entered Medina in 1806, they demolished many Islamic shrines and even planned to destroy the grave of Muhammad, which allegedly had led to polytheistic tendencies among Muslims. Stone idols, sacred trees, or rocks over which some Bedouin engaged in pre-Islamic religious acts of devotion were the original primary targets of destruction in Wahhabism's military campaigns. It was the Shiite adoration of Muhammad's son-in-law, Ali, and the almost divine attributes they assigned to him and his successors, from Hasan and Hussein, right out to the Twelfth Imam, that caused the Wahhabis to detest Shiism in particular, starting with the 1802 sacking of the Shiite holy city of Kerbala.

This Wahhabi insistence on destroying holy sites that might lead to polytheistic practices has in fact survived to the present day. No less that Sheikh bin Baz himself issued a fatwa in 1994 reading, "It is not permitted

to glorify buildings and historical sites. Such action would lead to shirk because people might think the places have spiritual value." 22 This was not just a theoretical legal judgement; it was put into practice in 1998—within Saudi Arabia itself—when the grave of Amina bint Wahhab, the mother of Muhammad, was destroyed by bulldozers and gasoline was then poured over the site. 23 It doesn't take much imagination to consider how the same authorities would treat ancient statues that were revered by other faiths if that is how they treated Islamic tombs. In short, the Taliban's destruction of the Buddhist statues in Bamiyan was an act that fit the Wahhabi world-view like a glove.

In fact, while the destruction in Bamiyan itself was the work of the Saudis' Taliban proteges, important clerical figures in the Saudi religious establishment issued fatwas explaining their religious support for the Taliban's demolition of the statues. For example, there was Sheikh Hamud bin Uqla al-Shu'aibi, a hard-line establishment cleric, who later would back al-Qaeda's September 11 attacks on New York and Washington. 24 A similarly militant cleric, who had been admired by Osama bin Laden, was Sheikh Sulayman bin Nasir al-Ulwan, who also issued a fatwa backing the Taliban action against the Buddhist statues. 25

These were not obscure individuals known only to the Saudi elites and their Taliban students. The writings of both these Wahhabi clerics had region-wide influence and were read by Islamic militants from Chechnya to Western Iraq to the Gaza Strip. The advent of the Internet simplified the worldwide proliferation of their ideas. For example, their religious rulings in support of suicide bombing attacks were featured on the website of Hamas, where a fatwa from a Saudi scholar was more common than the writings of Palestinian Islamists. 26

This ideology was also disseminated through printed Wahhabi texts from Mecca. The writings of Sheikh al-Ulwan that appeared in such texts were studied in one of the top Hamas schools in the Gaza Strip, called the Dar al-Arqam Model School. Finally, with its oil wealth, Saudi Arabia was able to offer generous scholarships to students from around the Middle East to study in hothouses of extremism like the Islamic University of Medina. Many Palestinians took up these offers, so that the rulings of

Saudi Arabia's clerical establishment, including its most militant elements, became easily accessible to the whole Muslim world.

In addition to the Wahhabi support the Taliban received for destroying the Buddhist statues, it is important to stress the position of Sheikh Yusuf Qaradhawi, the most important spiritual authority for the worldwide Muslim Brotherhood, including its Palestinian branch, Hamas (see below). Qaradhawi's views were doubly important because of his regular appearances on the al-Jazeera news network, where he had his own television program. Despite his open support for abducting and killing Americans in Iraq, he was often received warmly in Europe, as he was during his 2004 visit to London, where he was hosted by Mayor Ken Livingstone. Initially, Qaradhawi opposed the assault on the Buddhist statues and made a high-profile trip to Afghanistan to urge the Taliban to halt their proposed destruction. He later explained on al-Jazeera that at first he opposed the attacks because he was concerned with their effect on the status of Muslim minorities in Buddhist countries. But after visiting Afghanistan, he changed his mind and actually praised the Taliban, explaining that they were concerned with outsiders coming to Afghanistan and worshiping the statues. 27

Qaradhawi also associated himself with a 2006 Egyptian Islamic ruling against ancient Egyptian statues, declaring that "the statues of ancient Egypt are prohibited." 28 In fact, once the attacks on non-Muslim religious sites were legitimized in Afghanistan, it was not surprising to see the phenomenon spread across the entire Middle East and beyond. Wahhabi missionaries were seeking to cleanse Central Asia of the practice of venerating Muslim saints. In Iraqi Kurdistan, Islamic militants affiliated with pro-Wahhabi groups like Ansar al-hlam destroyed the graves of religious scholars, belonging to the Naqshabandi Sufi order, at which local Muslims recited prayers. In fact, in a July 2002 press release, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, led by Jalal Talabani, compared one such assault in a place called Bakhi Kon to the Taliban attacks on the Buddhist statues. 29 In April 2006, Talabani was elected the president of the new Iraq.

All these trends toward increasing religious intolerance converged in Iraq during the Sunni insurgency after the downfall of Saddam Hussein. The Sunni militant organizations that were heavily motivated by the

Wahhabi interpretation of Islam focused much of their internal campaign against the Iraqi Shiite population and its religious institutions. Shiite mosques were regularly targeted by Sunni suicide bombers. The most dramatic attack was carried out on February 22, 2006, by a team of two Iraqis and four Saudis who detonated bombs in the 1,200-year-old al-Askariya Mosque in Sammara, destroying the mosque's golden dome. 30

The special sanctity of the al-Askariya Mosque was derived from its location as the burial place of the tenth and eleventh Imams, according to Shiite tradition. Additionally, it was regarded as the place where the Twelfth Imam vanished and went into hiding in 874. The attack represented an unprecedented escalation in the severity of the war on religious sites. There had been Sunni attacks on Shiite shrines in Iraq before; besides the 1802 Wahhabi assault on Kerbala, in 1843 an Ottoman Sunni governor stormed the shrines of Hussein and Abbas in Kerbala and desecrated them by turning them into stables. 31 But the internal war roiling Iraq since 2004 has been far more intense than anything that has occurred before. And modern war on holy sites quickly became contagious in Iraq's sectarian conflict; on the day after the attack on the al-Askariya Mosque, Shiite militas in turn attacked twenty-seven Sunni mosques in Baghdad, using small arms, rocket propelled grenades, and mortar rounds.

This intra-Islamic violence had direct implications for the dwindling Christian communities of the Middle East and South Asia, who also faced more attacks during this period. In October 2001, radical Islamists opened fire inside a Catholic church in Bahawalpur, Pakistan, killing fifteen men, women, and children. Sectarian bombings of Pakistani Shiite mosques were also on the rise at the same time. There were no Shiite mosques in Egypt to destroy, but nonetheless attacks against Coptic Christians increased, including the massacre of twenty-one Christians in southern Egypt in early 2000. Eventually, the intensifying persecution of Christians and other non-Muslims by radical Islamists could no longer be ignored. 32

The Winds of Intolerance Hit the Palestinians

How these trends affected the Palestinian Arabs during the same time period requires special consideration for the issue of Jerusalem. The

dominant political force in Yasser Arafat's Palestinian Authority (PA) was al-Fatah. Its founders in the 1960s included a number of Muslim Brotherhood sympathizers, but it nonetheless sought to be perceived as a movement that would protect Christian and Muslim interests through its international arm, the PLO. Arafat spent a tremendous amount of energy cultivating a relationship with the Vatican, earning repeated audiences with the pope. The declared PLO goal for decades had been the replacement of Israel with a secular democratic state of Palestine.

Nonetheless, on the ground, the situation of Christians in areas controlled by the PA appeared to worsen in the 1990s. The PA itself was formed in 1994, a year after the signing of the Oslo Accords. The PAs draft constitution guaranteed that it would respect all monotheistic religions and guarantee freedom of worship, but also established Islam as the official religion and Islamic law as the primary source of legislation. 33

And whatever were the principles of governance that Arafat announced, in parallel to his Palestinian Authority there was the Hamas movement. A militant Palestinian Islamist terrorist organization established in 1987-88, Hamas steadily gained strength throughout the 1990s. Fatah and Hamas were political rivals, and Arafat was even willing to have its members arrested in 1996 in reaction to U.S. pressure following a devastating series of Hamas suicide bombings that killed upwards of ninety Israelis.

But Arafat was also willing to closely collaborate with Hamas, signaling to its leadership that it should resume bombing attacks when it suited his interest, as was the case in March 1997. And since Fatah had no independent body of clerics, Hamas religious leaders were frequendy employed by the Palestinian Authority. This collaborative relationship evolved to the point that Hamas eventually became a full military partner of Fatah in the confrontation with Israel in 2000. Fatah militias like the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades began engaging in suicide bombings, following the lead of the Hamas religious leadership.

In this context, it is important to remember that Hamas declared itself in its founding charter as the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, whose own record with respect to Christian Copts and local Jews in

Egypt was extremely poor. Historically, the Muslim Brotherhood regarded them both as foreigners who had exploited Egypt's natural resources. It was the Muslim Brotherhood that first coined the language of "the Zionist-Crusading War" that would become one of the main idioms of al-Qaeda years later. 34 Its literature traced much of European imperialism to the political machinations of the Church: "The West surely seeks to humiliate us, to occupy our lands and begin destroying Islam by annulling its laws and abolishing its traditions. In doing this, the West acts under the guidance of the Church. The power of the Church is operative in orienting the internal and foreign policies of the Western bloc, led by England and America." 35

Sayyid Qutb, the prolific ideologue of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood in the 1960s, would develop this theme further, blaming imperialism on "the Crusader spirit which runs in the blood of all Westerners." Subduing the Church was a constant theme of the organization's chief ideologues.

In short, the roots out of which Hamas grew were imbued with a strong anti-Christian predisposition above and beyond its more well-known anti-Israel positions. Hamas was a politically astute Islamist movement; it forged tactical alliances with local Palestinian Christians and even accepted them to its electoral slates. But its long-term ideological program for any territories that came under its control was molded by its affiliation with the Muslim Brotherhood and financial donations from Saudi Wah-habi charities which, by 2003, accounted for between 50 and 70 percent of its annual expenditures.

The effects of the arrival of Arafat's regime in the 1990s became most noticeable in the city of Bethlehem—the birthplace of Jesus and the location of the Church of the Nativity. Back in 1990, before the advent of the PA, when Bethlehem was under the Christian mayor Elias Freij and Israeli military control, Christians enjoyed a 60 percent majority in the city. This figure fell to 20 percent by 2001. 36 There were multiple causes of this dramatic demographic shift. Arafat gerrymandered Bethlehem's municipal boundaries to include large Muslim populations nearby, while his PA encouraged Muslims to immigrate to Bethlehem from Hebron and built large-scale housing projects for them there.

But there was also a massive emigration of Christians from Bethlehem. Contributing to this exodus was mounting social and economic discrimination as well as an environment of growing anti-Christian incitement. There were also many cases of land theft in which Christians were forced off their properties by an "Islamic fundamentalist mafia." 37 Holy sites were increasingly affected as well. Khaled Abu Toameh, the Arab affairs reporter of the Jerusalem Post, reported cases of Palestinian Muslims breaking into Christian monasteries to steal gold and other valuables. Christian cemeteries were also vandalized.

Priests and nuns were unable to stop these attacks and they received no help from the Palestinian security services. The Palestinian Anglican bishop, Riah Abu al-Assal, explained the growing anti-Christian environment in terms reminiscent of the views of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt: "Unfortunately, for Middle-Eastern Christians, we are perceived by some Muslims as stooges of the West. The extremists look on us as enemies." 38

In this environment, religious sites generally lost the immunity that they had enjoyed in the past. This became particularly evident in the Palestinian war against Israel, known as the Second Intifada, at the beginning of which Joseph's Tomb in Nablus and the Shalom al-Yisrael Synagogue in Jericho were attacked by armed mobs and desecrated. Christian holy sites became targets as well. In October and November 2000, gunmen from Fatah's Tanzim militia took up positions near the churches of the mostly Christian town of Beit Jalla, next to Bethlehem, in order to open fire into the nearby Jewish neighborhood of Gilo. One Christian cleric noted the case of the Church of St. Nicholas where, he explained, Arafat's Tanzim militia hoped Israel's return fire would hit the church, sparking front-page headlines about Israeli attacks on churches. 39

These attacks culminated in the dramatic invasion of the Church of the Nativity on April 2, 2002, when thirteen armed Palestinians from Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and Arafat's Tanzim militia blew open the church compound, forced their way inside, and seized clergymen as hostages. Wanted by the Israeli army, the gunmen seized the church knowing that the Israelis would be loath to raid a Christian holy site. While holed up inside, the terrorists looted church valuables, desecrated Bibles, and

planted bombs (which Israeli soldiers ultimately defused). After nearly six weeks, the attackers emerged as part of a deal sending them off to exile in Europe. 40 This single event illustrated the strikingly divergent attitudes held by the Israeli soldiers and Palestinian armed groups, respectively, toward the sanctity of Jerusalem's holy sites.

As already noted, Hamas was a full military partner of the Palestinian Authority, the latter having been led by Arafat's Fatah movement during the early years of the intifada of 2000. At that time both movements worked together under a common umbrella or joint command called "The National and Islamic Forces." In the West Bank the National and Islamic Forces were commanded by Marwan Barghouti, the local head of Fatah.

Yet by 2006, Hamas was no longer a junior partner of Fatah, for in that year it won the Palestinian parliamentary elections. Just prior to the elections, a Hamas member of the Bethlehem city council suggested that the traditional Islamic tax on non-Muslims, they/cytf or poll tax, be reinstated for Palestinian Christians as part of the imposition of Islamic law. In this new environment, George Cattan, a Palestinian intellectual, warned that the growing power of Palestinian Islamic movements was compromising the status of Christians and their holy sites: "In the West Bank and Gaza, armed Islamic movements regard Palestine as a Muslim ivaqf [religious endowment], and call to defend the places holy to Muslims while disregarding the places holy to Christians." 41

The Assertion of Palestinian Exclusivity in Jerusalem

To ascertain how all this affected Jerusalem during the period from 1993, when the Oslo Agreements were signed, until 2006, when Hamas won the Palestinian parliamentary elections, we must briefly review the Holy City s status during these years. Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin may have launched the Oslo Accords in 1993, but he was determined to keep Jerusalem united under the sovereignty of Israel. Even the Israeli-Palestinian implementation agreements clarified that the jurisdiction of Arafat's Palestinian Authority would not apply to areas that were to be discussed in future final status talks—and Oslo defined Jerusalem onlv as a future subject of negotiations. 42 In short, the Palestinians had no legal

standing in the Holy City according to the agreement that they themselves had signed.

Nonetheless, there were a number of ways through which Arafat's men sought to increase their power and influence in Jerusalem. While Rabin sought to enshrine Jordan's traditional status as the administrative caretaker of the Islamic shrines on the Temple Mount through the 1994 Washington Declaration and the subsequent Treaty of Peace between Israel and Jordan, his foreign minister, Shimon Peres, sent a secret letter of assurances to the PLO a year earlier on October 11, 1993, through the Norwegian foreign minister, Johan Jorgan Hoist, assuring the continuation of Palestinian institutions in Jerusalem.

The PLO applied this Israeli assurance liberally. It created a Ministry for Jerusalem Affairs that was headed by Faisal al-Husseini, who was not a full voting member of the Palestinian cabinet, in order to preclude any Israeli protests about PA governmental activity in Jerusalem. This was a transparent ploy to begin penetrating Jerusalem contrary to the Oslo Accords, but it was backed by many European states whose foreign ministers visited Husseini's Jerusalem headquarters in Orient House.

Moreover, in the religious sphere, during September 1994 Arafat established the Palestinian Authority's Ministry for Waqf Affairs in East Jerusalem under Hasan Tahboub. This was an affront not only to Israel but also to Jordan, which had been recognized as the paramount authority in the Muslim shrines on the Temple Mount. Indeed, a month later, when the Jordanian-appointed mufti of Jerusalem died, the PLO rushed in and appointed its own mufti, Sheikh Ikrima Sabri, who managed to win out in a struggle for influence with his Jordanian competitor. Sabri was an extremist; born in 1939, he already belonged to the Muslim Brotherhood during the period of Jordanian rule in the West Bank.

The Israeli government took no action since it was torn between Rabin's pro-Jordanian approach to the holy sites in Jerusalem and Peres's commitments to the PLO. The Clinton administration, which had hosted and witnessed the signing ceremonies for the Israeli agreements with the Palestinians and Jordan, did not get involved. But this Palestinian Authority takeover, even if it was confined to issues of religious administration,

was significant, for the Palestinian Waqf had been heavily penetrated by Hamas as well.

In the period that followed, numerous incidents demonstrated that the new Palestinian religious authorities were seeking to erode aspects of the previous status quo at Jerusalem's holy sites. The most dramatic of these occurred on April 9, 1997, when representatives of the Greek Orthodox Church alerted the Jerusalem municipality that Muslim workers associated with the al-Hanake Mosque, which was next to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, had broken into rooms belonging to the Greek Patriarch and annexed them to the mosque. After these rooms were added to the mosque, they were sealed off to the area controlled by the Greek Patriarch. 43

The entire initiative had been authorized by the Palestinian Authority Waqf. The main workers active on the site, however, were actually Israeli Arabs from Haifa and Jaffa who belonged to the Islamic Movement in Israel, which was a subsidiary of the Muslim Brotherhood and closely allied with Hamas. 44 The leader of its militant northern faction, Sheikh Ra'id Salah, was in contact with Sheikh Yusuf Qaradhawi on many issues. 45 Qaradhawi brought in the full ideological legacy of the Muslim Brotherhood. Although asked to head the organization, he instead emerged as its main spiritual guide. As noted before, Qaradhawi ultimately supported the actions of the Taliban against the Buddhist statues in Afghanistan's Bamiyan Valley. Now he was influencing Sheikh Salah.

Salah became a hard-liner; unlike the leadership of the southern faction of the Islamic Movement in Israel, he refused to let his members participate in national parliamentary elections. 46 Perhaps his family background contributed to the positions he adopted. He came from a Syrian Druze family that had converted to Islam before moving to Palestine. 47 He built up a close partnership with Dr. Mahmoud al-Zahar, the Hamas leader, who would become the Palestinian Authority foreign minister after Hamas won the 2006 Palestinian elections. He led delegations of his movement to meet with Sheikh Ahmad Yassin, the founder of Hamas. It was generally assumed that his faction benefited from the financial networks of the Muslim Brotherhood, based in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. 48

In the meantime, these workers began building a new two-stow structure in the mosque courtyard in a place that was adjacent to the northern wall of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The mosque had no building permit for the structure, which was intended to be a study hall for the Sufis. The al-Hanake Mosque dated back to the twelfth century and was dedicated by Saladin for the use of a Sufi order in Jerusalem, which still controlled the site. To make matters worse, all this construction eventually collapsed an internal wall inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. In another era, a threat of this sort to one of the holiest sites in Christianity could have sparked a war.

What also made this added construction effort especially controversial was that it included a bathroom on the second floor that also shared a common wall with the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The Fransciscans were enraged by this Muslim construction initiative. They noted that the roof of the new building was two feet higher than the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which in their view constituted an added provocation, for they felt it was intended to demonstrate the superiority of Islam over Christianity. 49 The whole situation had become explosive.

Israel preferred that the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan use its influence with the al-Haneke Mosque to correct the situation. Turning to the Palestinian Authority would be completely self-defeating since it would only enhance the status of the PA in the heart of the Old City. Moreover it was the PA-controlled Waqf that was backing the assault on Church properties. But even the Jordanians were unable to dislodge the Islamic Movement and the al-Hanake Mosque from the Greek Orthodox rooms. Jordan simply offered the Greek Orthodox Church an ancient Byzantine church near Kerak that had been turned into a mosque. In exchange, the Greek Orthodox Church dropped its claim to the two rooms next to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. 50

The immediate crisis appeared to be defused. However, the Palestinian Waqf undoubtedly emerged from the incident emboldened, since it was able to overturn the status quo in Jerusalem and get away with it. Moreover, it had expanded the area where it could exercise control in the heart of one of the most sensitive holy sites in the Middle East. It was only

a matter of time before a similar effort would be attempted in another potential tinderbox on the Old City of Jerusalem: the Temple Mount.

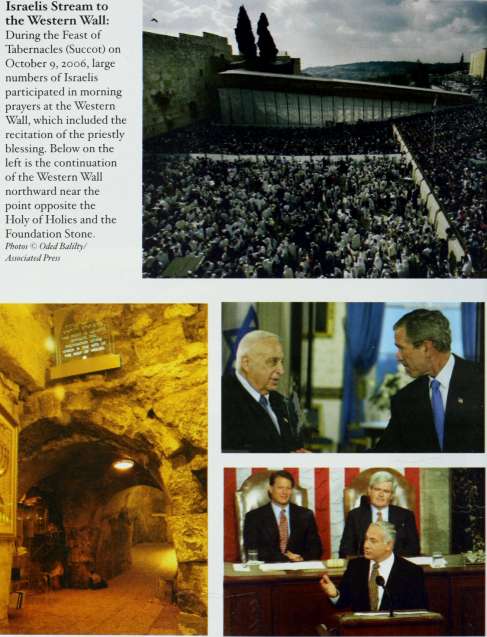

This upcoming clash would become evident in two stages. For years, Arab states had voiced their opposition to Israeli efforts to complete the development of the Western Wall area that formally began not long after the 1967 Six-Day War. The exposed area of the Western Wall used as a center of Jewish prayer was only 187 feet wide. There was another 1,050 feet of the Western Wall along the Temple Mount that was underground and which Israel completed excavating in the late 1980s. In 1991, the Western Wall Tunnel was officially opened, but it reached a dead end at the northwestern corner of the Temple Mount, requiring visitors to double back in order to exit to the outside world.

It would have made more sense for Israel to open up the northern end of the tunnel so that tourists could exit without having to do a U-turn and walk back the entire distance of the narrow underground tunnel. Tourists leaving the tunnel at the northern end would also pour into the tourist shops in the area of the Via Delarosa and increase the business of many Palestinian Arab shopkeepers.

The tunnels were full of rich archaeological discoveries including rooms from the times of King Herod, ballistae fired from Roman catapults against the Jewish defenders of Jerusalem during the Great Revolt when the Temple was destroyed, and many toppled stones from the Roman destruction from the Temple Mount above. Along the tunnels was the original masonry holding up the Temple Mount—including a 45-foot long stone weighing at least 550 tons. And at one area of the subterranean wall was a clearly marked point that designated where the Holy of Holies was located above. The potential for traffic of religious pilgrims from all over the world was enormous. Nonetheless, Israeli officials understood the sensitivity of the Islamic authorities to any changes in the area of the Temple Mount, so that even something as simple as the opening of an exit was usually proposed in consultation with the Waqf.

An opportunity to reach a quiet understanding over the opening of the Western Wall tunnel arose in early January 1996, when the Waqf authorities turned to the Israeli government, headed by Prime Minister Shimon

Peres, with a request to open up the heretofore sealed halls on the Temple Mount, known as Solomon's Stables, for Muslim prayers during Ramadan, when the numbers of Muslim visitors increases and there is a need for a covered area to give them shelter from the winter rains. Solomon's Stables, which included many subterranean halls, did not date back to the time of the United Monarchy of ancient Israel, but was actually a huge and largely abandoned structure that was used for stables by the Knights Templar after the First Crusade.

Neither side had an interest in giving the other a written agreement which stated that in exchange for opening up Solomon's Stables at the end of Ramadan, the northern end of the Western Wall Tunnel would be opened. In the past, agreements of this sort were usually concluded orally or in the form of a quiet mutual acquiescence to each side's requests. Representatives of the Minister of Police were absolutely certain that they had reached such a quiet quid pro quo from the Waqf authorities and reported this back to the Peres government. It was a strictly oral understanding. After Peres lost the 1996 elections to Benjamin Netanyahu, the new government apparently based its understanding of the Western Wall Tunnel/Solomon's stables tradeoff on a January 24, 1996, protocol from Peres's security cabinet. 51

Following the election, however, the Palestinian Waqf stridently denied that it gave any acknowledgement of Israeli rights to open up the Western Wall Tunnel, while at the same time it significantly expanded upon the rights Israel granted the Waqf in Solomon's Stables, turning a one-time permit to use the area on Ramadan alone in the event of rain, into a license to construct an entirely new and permanent mosque inside the Temple Mount—for the first time in hundreds of years. The new mosque was to consist of Solomon's Stables and another underground structure known as the Ancient al-Aqsa Mosque.

From January 1996 through the rest of the year, the Waqf, assisted by Israeli Arab volunteers from the radical faction of the Islamic Movement, worked feverishly to complete the new mosque that covered an area of 1.5 acres. They claimed that the Ummayad caliph Marwan, the father of the caliph Abd al-Malik who built the Dome of the Rock, had used Solomon's

Stables as a mosque or prayer room in the past, although there was no historical proof of this. Most of the initial work involved installing huge amounts of marble flooring and lighting. On December 10, 1996, they opened the mosque with a mass prayer of 5,000 Muslims, although the area of the new mosque could have housed double that number. 52 The volunteers from the Islamic Movement were not seeking to take over control of the Temple Mount from the Palestinian Authority Waqf. To the contrary, they appeared to be fully coordinated.

As the work proceeded, the Israeli government could have sought to halt what the Waqf was doing without a building license. Instead, it preferred to assert Israel's sovereign rights in another area of the Temple Mount by opening up the northern end of the Western Wall Tunnel. Late at night on September 23, 1996, at the end of the Jewish fast of Yom Kip-pur, Prime Minister Netanyahu ordered the stones sealing the northern end of the Western Wall tunnel to be knocked out and an exit for the tunnel to be created. His cabinet based its decisions on the understandings that had been quietly worked out months earlier by the Peres government.

Arafat immediately launched an international campaign to force Israel to seal up the opening. He recruited the Arab League, which repeated his charge that the purpose of the tunnel was to collapse the al-Aqsa Mosque and to construct in its place a new Jewish Temple. In an official complaint to the UN Security Council, the Saudi representative to the UN sought action against Israel's "opening an entrance to the tunnel extending under the Al-Aqsa Mosque in occupied East Jerusalem." 53

Of course, the Western Wall tunnel was not even near the al-Aqsa Mosque—it did not go under the Temple Mount, but rather followed a path that went parallel to the Temple Mount's western side. Nonetheless, despite the fact that the Saudi letter contained essential erroneous facts, it was not dismissed out of hand by the UN and would trigger full consideration of the Western Wall Tunnel by the Security Council.

The chronology alone should have led the Security Council to dismiss the Saudi letter. Most of the tunnel's excavation was completed back in 1987 and no damage was caused at the time to the area of the Muslim shrines; as already noted, that last stretch of the tunnel was dug out in

1991, and it involved uncovering a pre-existing tunnel that had been an aqueduct in Hasmonean times. In short, there was no new digging that had transpired in 1996 and certainly nothing remotely close to the al-Aqsa Mosque. All that had occurred was that a two-foot thick wall at the far end of the tunnel had been opened, so that it could be exited on both its ends.

The campaign against the Western Wall Tunnel had two aspects. First, after the UN Security Council considered the Saudi letter, it adopted Resolution 1073 that called for "the immediate cessation and reversal of all acts which have resulted in the aggravation of the situation, and which have negative implications for the Middle East peace process." This was an implicit call on Israel to seal the Western Wall Tunnel and it had the support of the Clinton administration, which could argue that the language of the resolution was softened and an explicit call on Israel to seal the tunnel was removed.

The second aspect of the campaign against the tunnel was more serious, for it involved outright violence. Initially there was no spontaneous reaction to the opening of the tunnel from the Palestinian street. As a result, the Palestinian Authority decided to incite mass rioting for three days; for the first time since the signing of the Oslo Accords, Palestinian security forces opened fire on Israeli soldiers, resulting in fifteen soldiers killed and about forty Palestinian fatalities.

The clear purpose of the international campaign and accompanying local bloodshed, which had been initiated by Arafat as well, was to force Israel to withdraw from exercising its sovereignty along the side of the Temple Mount, while the Palestinians would complete uninterrupted their effort to totally alter the status quo on top of the Temple Mount by finishing off their new mosque in Solomon's Stables.

Ironically, if any construction initiative threatened the stability of ancient structures on the Temple Mount or its outer walls, it was the completion of this new mosque and not the opening of the Western Wall Tunnel. Solomon's Stables were right next to the al-Aqsa Mosque, while the northern end of the Western Wall Tunnel was roughly 1,000 feet away. The goal here was Palestinian exclusive control of the Temple Mount and not some kind of modus vivendi between two monotheistic faiths. This was

clearly a political battle for the future of Jerusalem and not a struggle based on any substance regarding the issues.

The efforts of the Waqf with radical elements of the Islamic movement in Israel to take over the Temple Mount continued. During 1997, the Waqf worked to take possession of another ancient structure that the Muslim authorities called the "Ancient Al-Aqsa" which was under the al-Aqsa Mosque and an adjacent school. It was opened for prayers during Ramadan 1999. The Waqf then argued that these underground mosques would need emergency exits. This led also in 1999 to it opening a huge gaping hole through which thousands of tons of ancient debris was removed and dumped in the neighboring Kidron Valley. Israeli archeologists sifting through this material found artifacts dating back to the First Temple period. 54

What was clear was that the Waqf workers did not want anyone else to go through the material they had removed or identify it. Stones with decorations and markings were recut. Apparently, there were discoveries that the Waqf sought to hide. For example, one Waqf worker claimed to have seen writing on some stones in ancient Hebrew. He also observed five-pointed Hasmonean stars. Moreover, the trucks carrying the debris from the Temple Mount were followed to Jerusalem's municipal garbage dump, where it was unloaded and mixed with local garbage in order to make it difficult to separate out any historically significant artifacts. When the municipal manager of the city dump was informed that the trucks contained archaeologically significant debris, he redirected them to a clean zone; but after four trucks were told to move to this new area, the rest of the trucks simply stopped coming to the municipal dump. 55

In July 2000, the director of the Waqf, Adnan Husseini, tried to clarify in the Washington Post what exactly the Palestinians were doing on the Temple Mount. He denied that any damage was caused to any archaeological remains. His argument had been proven patently false in light of what had been already found in the rubble the Waqf had removed from the Temple Mount and discarded in various dump sites around Jerusalem. He then explained why they were building new mosques like the "Al-Marwani Prayer Room" in Solomon's Stables: "The Waqf's work on the Haram

al-Sharif is being done in anticipation of the thousands of Muslim pilgrims who will be able to visit the Haram after Palestinian-Israeli peace." 56

It was a weak argument since the Waqf's work on Solomon's Stables began in 1996, well before any negotiations over the future status of Jerusalem were held. But Husseini had revealed an important intention of the Palestinian Authority, in the event that it secured the Temple Mount and most of the Old City in negotiations: to open up Jerusalem to much larger scale Muslim pilgrimage than the city had ever received before. Reliable sources close to the Palestinian Authority indicated that the PLO was considering new plans for eliminating many buildings in the Old City of Jerusalem to make way for new hotel construction on a massive scale in order to house the thousands of pilgrims that it hoped to attract.

By September 2000, Arafat launched a new round of violence against Israel, the pretext of which was the visit to the Temple Mount of Ariel Sharon, who headed at the time the Israeli parliamentary opposition. According to the Palestinian Authority minister of communications, Imad Faluji, the outburst of Palestinian violence that followed was pre-planned by Arafat months earlier; nonetheless, he would call his new war the "Al-Aqsa Intifada" in order to convey the idea that the al-Aqsa Mosque was somehow endangered and hence needed to be defended. 57 Exploiting this new political environment that Arafat had created, the Palestinain Authority Waqf took one more step to assert its claim to the area of the Temple Mount; it unilaterally closed off the area to regular inspections from the Israel Antiquities Authority. The Waqf also barred non-Muslim visitors from the Temple Mount.

With Israeli oversight removed, much of the heavier work on the underground mosques could move forward without any concern about its possible disclosure. In total, some 13,000 tons of unsifted archaeological rubble had been removed to city garbage dumps and other sites. A heavy saw was introduced inside the Temple Mount that was being used to cut and destroy ancient columns. Ironically, it was during this period that the Clinton administration and the Barak government were working feverishly to conclude an Israeli-Palestinian final status accord that would have divided the Old City of Jerusalem and granted formal recognition of Palestinian control of the Temple Mount.

In early 2001, both Clinton and Barak were replaced. Still, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon understood how a direct clash with the Waqf over the Temple Mount could ignite the whole Islamic world. As a result, his government undertook quiet measures intended to end the enormous damage caused by the Waqf activities. Primarily, he sought to limit the introduction of heavy equipment and machinery into the area of the Temple Mount. Bulldozers and heavy dump trucks would no longer be permitted to enter the Temple Mount to remove tons of ancient remains, although some heavy equipment was still spotted at times by groups of private citizens who reported these instances to the Israeli authorities.

The Waqf efforts, however, were not completely halted. Hundreds of Israeli Arab volunteers still streamed into Jerusalem to work on various new projects. The use of Israeli Arab manpower provided a regular supply of laborers, since the arrival of West Bank Palestinians might be halted in the event of a deteriorating security situation. As a result, by working together, the Waqf and the militant faction of the Islamic Movement in Israel continued their efforts to stake out an exclusive claim over the Temple Mount once their heavy construction projects were arrested.

For in the meantime, the Islamic Movement discovered thirty-seven underground chambers inside the Temple Mount, some of which have large halls. It has undertaken a fundraising drive throughout the Arab world to renovate these areas. Israeli authorities assumed that the work on these underground rooms was being undertaken to build additional mosques or to create a system of passageways connecting a network of prayer halls that the Waqf hoped to create. This would have converted the whole Temple Mount into one huge mosque, and could be used as yet another reason for keeping non-Muslims out of the area. The Sharon government ordered the clean-up of the underground areas halted in August 2001 after only a few of these large halls had been prepared. 58

The following month, however, the Islamic Movement planned to import water from the Zamzam well in Mecca and pour it into ten cisterns that it had uncovered on the Temple Mount. According to Islamic tradition, the Zamzam was a spring that miraculously appeared before Hagar and Ishmael in the desert after they had exhausted the water they had in their possession upon leaving Abraham. The Zamzam well is located inside

the Grand Mosque in Mecca and is only a short distance from the Ka'bah. Its waters come from the heart of the holiest site in Islam. During the first day of the hajj, pilgrims to Mecca drink Zamzam water as one of the religious rites that they perform.

While Zamzam water may be drunk outside of Mecca and is often given to the sick, since it is viewed as having a degree of holiness, it is associated with a religious ceremony that is performed only in Mecca. This raises the question of what the Israeli Islamic Movement planned to do with the Zamzam waters they hoped to store in great quantities on the Temple Mount. Some interpreted this act as an effort to elevate the holiness of Jerusalem for Islam to a status comparable to that of Mecca. True Muslim conservatives would have raised their eyebrows had the plan been implemented; going back to Ibn Taymiyyah, they had always objected to the adoption of Islamic religious rituals in Jerusalem that were normally reserved for Mecca. The sponsors of the project admitted that its purpose was to increase the number of Muslim visitors to the al-Aqsa Mosque. 59 In practical terms if Islamic authorities could argue that Jerusalem and Mecca shared the same sanctity, then they might also rule that non-Muslims must stay away from the Temple Mount, just as non-Muslims are forbidden to enter the area of Mecca. The Islamic Movement in Israel admitted that it had received the support and financial assistance of a number of international Islamic organizations, although it did not reveal their identities.

What seemed certain was that behind this plan was an effort to link directly the sanctity of Jerusalem to that of Mecca and thereby mobilize even greater support for the continuing efforts of the Waqf and the Islamic Movement to take over the entire Temple Mount. Despite all the difficulties, Israeli authorities succeeded in preventing the completion of the Zamzam waters project. The Islamic movement had hoped to ship the holy waters from Saudi Arabia to Jordan by tanker, and then to Jerusalem via the West Bank. Ultimately, the plan was successfully halted.

As with the earlier efforts of the Waqf to destroy Temple Mount antiquities, Israel needed to adopt a number of counter-measures to halt the anarchical situation developing under the religious administration of the Palestinian Authority. But it also needed to be certain that it would not

provide an excuse for Arafat to incite a new religious war in response. This required a carefully calibrated strategy. Prime Minister Sharon had rolled back the Palestinian Authority presence in Jerusalem back in August 2001, when he closed down Orient House, the un-official PLO headquarters in East Jerusalem. This reassertion of Israeli control transpired without any incident.

The Temple Mount was a far more delicate matter. The Israeli government took its first move there in August 2003, when it reopened the Temple Mount to all international visitors after it had been closed off to non-Muslims for three years. The Israeli government insisted that the Temple Mount, which was one of the most important holy sites in Jerusalem, be made accessible to people of all faiths, in accordance with Israeli law. It was a principle that even the UN Security Council could not oppose.

The following year, Israel sought quietly to restore Jordanian influence on the Temple Mount and cut back the powers of the Palestinian Authority. Reportedly, Jerusalem's chief of police made a number of secret visits to Jordan for this purpose. Jordan raised approximately $4 million to repair the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque, as it had done in the past, and thereby asserted its continuing role in the area in a very public way. Jordan had been paying Waqf salaries for years even in the period of Palestinian religious administration, but it now sought to be more assertive with these employees, who were apparently pleased with Jordan's rising interest. Moreover, the Waqf building projects over the last number of years on the Temple Mount had weakened its southern wall; Jordanian engineers arrived to suggest repairs. 60

Nonetheless, the years of Palestinian Authority control had created the conditions that facilitated the infiltration of militant ideologies. These would be hard to counter, for throughout this period the Friday sermons given on the Temple Mount also became increasingly radical. The themes raised appeared to follow much of the jihadist agenda advanced by spokesmen of al-Qaeda. For example, an April 11, 2003, sermon attacked the current leaders in the Arab world describing their governments as "heretical Arab regimes." Since 2000 this had become a common theme in various

Temple Mount sermons. And, on November 12, 2004, Sheikh Yusuf Sneineh, one of the senior preachers in the al-Aqsa Mosque spoke before 32,000 worshipers at Friday prayers. He also called for the creation of a new caliphate, explaining that the only solution to the problems facing the Palestinians was the establishment of an Islamic state, whose flag will fly over the Temple Mount. The new state, he proposed, would be headed by an Islamic caliph. 61 While Jerusalem had never been the seat of any of the great caliphates of Islam in the past, there were calls among some clerics to convert the Holy City into the capital of the new Islamic caliphate they hoped to create.

The Palestinian Authority-appointed mufti, Sheikh Ikrima Sabri, added strongly anti-American themes to the Temple Mount sermons. Weeks before September 11, Sabri had gone so far to declare before worshipers, "Allah, bring destruction on the United States, on those who help it and on all its collaborators." He also called for the destruction of Great Britain. 62 His militant anti-Americanism continued years later. For example, on December 3, 2004, he charged the U.S. with waging a cultural war against Muslims, which was part of the "Crusader-Zionist attack on Islam." It was notable that these themes were still being voiced even after the death of Yasser Arafat and his replacement by Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen), who had been courted by the Bush administration. It probably reflected the weak control of the Fatah leadership over the religious elements in the Palestinian Authority who were coming under the influence of other movements.

Multiple sources for this radicalization of the Temple Mount sermons can be identified. There were Hamas members who infiltrated the Temple Mount—like Sheikh Hasan Yousef, who spoke to a crowd in front of the al-Aqsa Mosque on April 10, 2005. Additionally, since September 2001, supporters of Hizb ut-Tahrir (the Islamic Liberation Party) aften gave brief sermons on the Temple Mount after the main Friday prayers in the al-Aqsa Mosque. 63 One of the organization's strongest proponents among the Palestinians was a preacher named Sheikh Issam Amayra, who gave a monthly sermon in the al-Aqsa Mosque following the afternoon prayers. He would also give a weekly course during the month of Ramadan at the al-Aqsa Mosque itself.

The entry of Hizb ut-Tahrir to the Temple Mount was significant and had international implications. Members of Hizb ut-Tahrir assailed Egypt's foreign minster, Ahmad Maher, in December 2003, when he came to pray in the al-Aqsa Mosque. They also sought to surround the First Lady, Laura Bush, when she visited the Temple Mount in May 2005, but she was protected by the U.S. Secret Service and Israeli security guards. Hizb ut-Tahrir was extremely hostile to existing Arab regimes and those who supported them. According to its own platform, its paramount mission was the reestablishment of the Islamic caliphate, which will rule over the entire Muslim world instead of the present governments. 64

Moreover, Hizb ut-Tahrir was regarded by Western analysts as an al-Qaeda precursor organization that provided ideological indoctrination to its members and thereby made them ideal recruits for more militant groups like al-Qaeda at a later stage; for this reason, one analyst called them "a conveyor belt for terrorists," meaning that once a Hizb ut-Tahrir member is adequately imbued with its radical Islamist agenda, he is ready to be passed along to groups that actually conduct military operations. 65 Hizb ut-Tahrir itself believed that the reestablishment of the caliphate was a prerequisite for declaring jihad. This distinguished the organization from the main jihadist networks like al-Qaeda. But like al-Qaeda it opposes all the existing regimes in the Islamic world and seeks their replacement. 66

Hizb ut-Tahrir was founded in Jordanian-controlled East Jerusalem in 1953 by a Palestinian judge named Sheikh Taqi al-Din al-Nabhani. He came out of the Muslim Brotherhood but he felt that it had been too accepting of what he viewed as the Judeo-Christian-dominated Western state system. 67 Its religious outlook was based on Wahhabism. Despite its origins, it did not specifically state that Jerusalem had to be the seat of the new caliphate; it did not disclose its territorial ambitions. 68 Over the years, Hizb ut-Tahrir established secret cells in dozens of countries, perhaps in as many as forty, including in many states in Europe and especially in the UK.

In much of the Arab world Hizb ut-Tahrir was illegal. The Germans belatedly outlawed the group in 2003; it had been revealed that September 11 mastermind Muhammad Atta had come under its influence. However, it was still active in Britain. Pakistani prime minister Pervez Musharaf

warned the British government in the London Sunday Times on July 31, 2005, to shut down Hizb ut-Tahrir, right after the July 7, 2005, London subway bombings, thereby linking the presence of the organization with the new internal jihadist threats facing Britain. It seemed that Hizb ut-Tahrir was crossing over into terrorism or at least preparing the groundwork for the infiltration of al-Qaeda in key locations around the world. 69

Now it appeared that Hizb ut-Tahrir had sympathizers among those Palestinians in Jerusalem who were giving sermons on the Temple Mount. Presumably, the Waqf was supposed to control who gave these sermons. The clerics who preached in the Temple Mount mosques were in many cases employees of the Palestinian Authority, for they also received funds from its Ministry of Waqf Affairs. Given that the Palestinian Authority was dependent on Saudi financial largesse and Egyptian political backing, it was surprising that it would permit such inflammatory rhetoric calling for the overthrow of the regimes that had been the bedrock of its support. The Waqf had clearly opened the door to the penetration of the Temple Mount by radical Islamist elements. Indeed, Hizb ut-Tahrir even held a mass rally on the Temple Mount on March 3, 2006.

Hizb ut-Tahrir was only a part of the problem that Jerusalem potentially faced. As already noted, several months earlier in January 2006, Hamas won the Palestinian Authority parliamentary elections and formed the new Palestinian government. In recent years Hamas had, in fact, shown signs of becoming even more radicalized. While to the international community it sought to distinguish itself from al-Qaeda, internally it appeared more ready to embrace aspects of its ideology and global agenda.

Thus a Hamas poster distributed in the West Bank in 2002 featured a portrait of its founder, Sheikh Ahmad Yassin, alongside portraits of the Chechen jihadist leader Khattab and of Osama bin Laden. The poster also listed the areas where global jihadist groups had been active: Afghanistan, Kashmir, the Balkans, and of course, Palestine. And when Israel completed its unilateral disengagement from the Gaza Strip in August 2005, Hamas leaders like Mahmoud al-Zahar, expressed their hope that the Israeli pull-out would strengthen the morale of the mujahidin fighting the coalition in Iraq. Al-Zahar would become the Hamas foreign minister after the 2006 Palestinian elections.

Finally, on March 20, 2006, the head of the Hamas political bureau, Khaled Mashaal attended a Hamas fundraiser in Yemen that featured Sheikh Abd al-Majid al-Zindani, who had been designated by the U.S. Department of the Treasury as an al-Qaeda supporter and spiritual advisor to Osama bin Laden. Known to have actively recruited operatives for al-Qaeda training camps, 70 al-Zindani had fought with bin Laden in Afghanistan in the 1980s. Less than a week after the fundraiser in Yemen, the Hamas leadership visited Peshawar, Pakistan, where it was in contact with leaders of a Kashmiri jihadist group with close ties to al-Qaeda. 71 Thus, despite its denials, Hamas was increasingly reaching out to the forces of global jihad with whom it ideologically identified, while it was simultaneously seeking to be legitimized by Western powers who were anxious to see the Israeli-Palestinian peace process resumed.

What all this meant for the future of Jerusalem was becoming increasingly clear. Any expansion of Hamas influence in Jerusalem through the Palestinian Authority would open the door for even more radical Islamic elements to establish themselves in the Holy City. This had already been demonstrated in the Gaza Strip; after Israel withdrew completely from Gaza, where Hamas was already the predominant political power, it should not have come as a surprise that Israeli military intelligence determined that al-Qaeda cells had successfully infiltrated the area.

Indeed, Palestinian Authority president Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen) verified the Israeli claim in the London Arabic daily al-Hayat on March 2, 2006, when he admitted that he too had received intelligence information indicating the presence of al-Qaeda operatives in both the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. Hamas made no effort to block al-Qaeda's infiltration efforts. It stood to conclude that if Hamas could harbor al-Qaeda cells in Gaza, then this might occur wherever Hamas could exercise its control. Potentially, Hamas was in a position in which it could easily repeat in 2006 what the Taliban had done a decade earlier by hosting terrorists associated with al-Qaeda.

What that could mean for the holy sites of Jerusalem had already become evident with the limited amount of authority that the Palestinians had taken from the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan during the 1990s. In the surrounding areas under Palestinian control, the visible signs of

religious intolerance were multiplying. Israel's withdrawal from the Gaza Strip in August 2005 was immediately followed by mob attacks on the synagogues it left behind, which were set on fire. More recently in September 2006, following the controversy in much of the Arab world over the remarks made by Pope Benedict XVI about how a Byzantine leader historically viewed Islam, two West Bank churches were hit by firebombs and a Greek Orthodox church in Gaza was attacked by two small explosive devices.

It seemed that in the Hamas-dominated Palestinian Authority there was a very short fuse that could be easily lit when unexpected events transpired with religious implications. Under such conditions, if Israel withdrew from most of the Old City of Jerusalem, as was proposed in the latter part of 2000, the future security of the holy sites of the three great faiths, as well as the freedom of Jerusalem more generally, would be clearly put at serious risk.

Chapter 8

Jerusalem as an Apocalyptic Trigger for Radical Islam

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran established in the most dramatic fashion a direct connection between radical Islam's apocalyptic outlook and the future of Jerusalem. Facing a UN Security Council deadline for answering the demands of the international community that Iran freeze the production of enriched uranium, Ahmadinejad's government stated that it would give its answer on August 22, 2006. That date corresponded to the twenty-seventh of the month of Rajab, according to the Muslim calendar. 1 In Islamic tradition, that was the date when Muhammad flew on a winged horse-like beast, al-Buraq, from Mecca to Jerusalem and ascended to heaven.

Ahmadinejad has been associated with a radical apocalyptic movement with Iranian Shiism known as the Hojjatieh Mahdavieh Society. Mainstream Shiites believe in the eventual return of the Twelfth Imam, who is a direct descendant of Muhammad's son-in-law, Ali, and whose family is viewed by Shiites as the only appropriate successors to Muhammad. The Twelfth Imam went into what Shiites call the "lesser occulation" in the year 874 by which he became invisible and communicated with the outside word through special agents until the year 940, when "the greater occulation"

began and his communication with his followers ended; the Twelfth Imam is expected to return in the future as the Mahdi ("the rightly guided one"). This event is expected to usher in a new messianic-like era of global order and justice for Shiites in which Islam will be victorious. The Shiite Mahdi is also supposed to "take vengeance on the enemies of God," although his arrival is an end of time concept for the distant future. 2

The Hojjatieh, which started out in 1953 as a movement against the Bahai faith, believe that the timing of this historical process is not predetermined; it can be hastened through apocalyptic chaos and violence. And Ahmadinejad has openly stated, "Our revolution's main mission is to pave the way for the reappearance of the Twelfth Imam, the Mahdi." 3 One Western reporter conveyed that Ahmadinejad may have told his cabinet that the Mahdi will arrive within the next two years. 4 From his statements it is clear that the Iranian president sees that it is within man's power to facilitate this process of the end of days. But how exactly is the Mahdi's arrival to be accelerated?

For Ahmadinejad, the destruction of Israel is one of the key global developments that will trigger the appearance of the Mahdi. 5 It was on Iran's annual "Jerusalem Day" on October 26, 2005, that Ahmadinejad made his famous reference to the need to "wipe Israel off the map." What did not receive the same attention was another part of his speech in which he said, "We are now in the process of an historical war between the World of Arrogance [i.e. the West] and the Islamic world." He then added that "a world without America and Zionism" is "attainable." 6 Thus Ahmadinejad was talking about a war against the U.S. and its Western allies.

A month earlier, in his first UN General Assembly address, Ahmadinejad closed with a prayer that the Mahdi's arrival be quickened: "Oh mighty Lord, I pray to you to hasten the emergence of your last repository, the promised one." 7 He was recorded saying that a member of his delegation noticed that he was surrounded by an aura of light during the twenty-seven to twenty-eight minutes that he spoke, which he admitted to have felt himself. 8 Ahmadinejad shows all the signs of not only using apocalyptic language, but also believing that he has a personal role in bringing the end of times about.

But what was the connection between Jerusalem and Ahmadinejad's planned final battle? Dr. Bilal Na'im served as an assistant to the head of the Executive Council of Hizballah, the Iranian-controlled Lebanese Shi-ite terrorist organization. In an essay discussing the details of how the Mahdi is supposed to appear before the world, according to Shiite doctrine, he states that initially the Mahdi reveals himself in Mecca "and he will lean on the Ka'abah and view the arrival of his supporters from around the world."

From Mecca the Mahdi next moves to Karbala in Iraq. But his most important destination, in Na'im's description, is clearly Jerusalem. It is in Jerusalem from where the launching of the Mahdi's world conquest is declared. He explains, "The liberation of Jerusalem is the preface for liberating the world and establishing the state of justice and values on earth." 9 In short, Jerusalem serves as the launching pad for the Mahdi's global jihad at the end of days.

Sunni Apocalyptic Movements and Jerusalem

This eschatological scenario is not unique to Shiism. In the last five years, there has been a discernable increase in apocalyptic discussions on Sunni jihadist websites, according to which there are now clear signs evident that the Day of Judgment is imminent. 10 There is a common misperception that preoccupation with the coming of the Mahdi occurred only in the world of Shiism; but in fact, Sunni Islam has generated a number of figures who claimed to be the Mahdi, including the famous Mahdi of Sudan who fought General Gordon and the British in the 1880s, and most recently Muhammad al-Qahtani, who with his brother-in-law, Juhaiman al-Utaibi took over the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979. 11

It should be noted that apocalyptic speculation goes back to the beginning of Islam. Indeed, an explanation for the energy and success behind the original Islamic conquests of the seventh century was the belief at the time that the Muslim armies were eradicating evil just before the day of judgment and the end of the world. 12

There have also been strong counter-currents in Sunni Islam against what might be called Mahdism. The great Islamic philosopher Ibn Khaldun

attacked Mahdism as a form of ideological infiltration of Shiism into the Sufi orders of Sunni Islam. 13 He doubted the reliability of the hadith literature about the Mahdi, questioning the lines of transmission of these oral traditions. 14 And of course the Ottoman Empire, which was headed by a Sultan who was also caliph of Sunni Islam, fought the Sudanese Mahdi along with the British. Thus there have been powerful voices in Islam against these apocalyptic trends in the world of Sunni Islam, treating Mahdism as almost a deviation from authentic Islam.

In the Koran, there in fact is no reference to the coming of a Mahdi. The end of time is called al-sa^a or "the Hour" and it appears in several dozen places in the Koran. There are also many more references in the Koran to "the Day of Resurrection." In the hadith literature, in fact, there is reference to Muhammad saying that he was sent "with a sword" just before the Hour arrives, indicating that at the time of the rise of Islam there was indeed a perception that the end of days was imminent. This was also true of the period of Muhammad's immediate successors. For example, the Muslim historian al-Tabari records a conversation between the second caliph, Umar bin al-Khattab, and a Jew who predicted his conquest of Jerusalem in which Umar asked as well about the coming of the false Messiah, known in Arabic as al-Dajjal. The Jew responded, "What are you asking about him, O Commander of the Faithful? You, the Arabs will kill him ten odd cubits in front of the gates of Lydda [near present-day Ben-Gurion international airport of Israel]." 15

Some of the current apocalyptic speculation began to return to be a part of public discourse back in the 1990s with the publication of a number of popular books that put forward a number of common scenarios. They often began with a region of Central Asia, called in many classical works "Khurasan," which apparently refers to Afghanistan, Turke-menistan, parts of Uzbekistan, and eastern Iran. The Mahdi is supposed to appear here and lead an army that will carry black banners and arrive in Iraq. In a 1993 version of this scenario, the army with its black banners is supposed to advance from "Khurasan" through the area of Iran in the general direction of Syria "with the ultimate goal of establishing the messianic capital in Jerusalem." 16

The tradition cited about the black banners comes from a hadith attributed to Muhammad that says, "Black flags will go out of Khurasan and nothing shall thwart them until they are firmly hoisted in Iliya [based on the old Roman name for Jerusalem, Aelia]." 17 The tradition grew in the eighth century when the Abbasids were seeking to overthrow the Ummayad caliphate, for which Jerusalem was an important symbol of power. 18 This historical context was now forgotten as events in the late 1990s and in the years that followed confirmed many of these apocalyptic scenarios for radical Sunni Muslims. The rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan seemed to resemble the legendary "Khurasan" from where the truly Islamic forces were to begin their advance in the Middle East. 19 For many radical Muslims, the Taliban's special role in the apocalyptic scenario was authenticated when they ordered the destruction of the Buddhist "idols" in the Bamiyan Valley during 1998. 20

The Taliban were not the only active party in "Khurasan." There were also jihadist forces in the area of Uzbekistan as well, including Hizb ut-Tahrir, whose presence in that area was substantial. A Palestinian radical named Salah al-Din Abu Arafa, writing in 2001, identified Osama bin Laden as an apocalyptic figure who will defeat and ultimately destroy the United States. His book was a bestseller in the territories controlled by the Palestinian Authority. 21 Detailed analyses on websites identifying with al-Qaeda have characterized the confrontation between radical Islam and the West as a sign of the impending Apocalypse, according to which bin Laden's forces are the army of the Mahdi that will eventually conquer Iraq, Syria, Palestine, and Bayt al-Maqdis —that is, Jerusalem. 22

Indeed, it is Jerusalem that plays a particularly critical role in most of these Sunni apocalyptic scenarios. Muhammad Isa Da'ud, an Egyptian who has been living in Saudi Arabia, has written the most detailed and comprehensive accounts about the coming of the Mahdi. He is also one of the most prolific authors in the Arab world on apocalyptic scenarios, having authored at least eight books on the subject in the course of the 1990s that were published in Cairo. But his works have not been endorsed by the clerical establishment. 23 In his book Armageddon and What Comes After Armageddon, he writes: "The Mahdi will come to Jerusalem and will enter

the building of the caliphate near the al-Aqsa Mosque, the place from which Muhammad ascended to Heaven which is a sign that that the Mahdi will go out from there with conquests and with the honor that he will provide the religion of Allah [for] he will take people out from darkness to light, sending the flag of Islam to all of the world."

What Da'ud describes is not a spiritual conquest of the world but an actual military campaign led by the Mahdi himself. A global war begins, in his narrative, after spies from Rome are caught in Jerusalem trying to assassinate the Mahdi. He then declares his army is moving toward the Vatican after it refuses to turn over the families of the assassins to Mahdi's custody. At that point a series of military campaigns in Europe begins. Sweden accepts Islam voluntarily and Denmark soon falls as well, providing the Mahdi with a northern European base. Britain and France are the last to fall after a ballistic missile attack. Da'ud concludes, "Then what will remain for the Mahdi of Europe is just Italy and the Vatican; at that point the Mahdi declares that it is time to destroy the Cross." 24

As for Jerusalem, Da'ud portrays a bloodbath. He anticipates that most Jews in Israel will be killed and that 85 percent of the Jews in the world will perish in the Mahdi's campaign. 25 He adds that the Mahdi will also purify Jerusalem of any buildings of Jewish vintage before he establishes die Mahdist capital in the Holy City. 26 This might be interpreted as a need to erase any record of a Jewish presence in Jerusalem or artifacts of a past Jewish civilization

One immediate question that arises from all this literature is its impact. How widespread are these books and are they affecting public opinion in any way? An Egyptian writer, Sayyid Ayyub, who wrote a book called al-Masih al-Dajjal {The Antichrist), was one of the first of the current wave of authors. 27 His work was described as a "runaway hit" in Egypt and appears to have generated hundreds of other books. 28 Even those who downplay the influence of Islamic apocalyptic literature on the public at large admit that it has a strong following among Islamic radicals. 29 The apocalyptic writings of the slain Saudi militant Juhaiman al-Utaibi, who seized the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979 and declared that Muhammad al-Qahtani was the Mahdi, appear on the most important jihadist online

library—that of Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, the former mentor of the late Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. 30

Bassam Jarrar, a high-ranking Hamas operative, wrote an apocalyptic work called The Disappearance of Israel in 2022, which he claimed sold 30,000 copies in the West Bank alone—given the relatively small size of the Palestinian population, one writer noted that this is like selling two million books in the U.S. 31 He reached this date by making mathematical calculations based on the number of times certain terms are mentioned in the Koran. Jarrar's influence was probably far greater than his book sales even indicate. He was known as one of the most prominent Islamist intellectuals on the West Bank. 32 He was also a representative of the Union of Good, an international umbrella organization of Islamic charities run by Sheikh Yusuf Qaradhawi, the greatest spiritual authority of the Muslim Brotherhood. 33

Jarrar also taped anti-Semitic lectures on audio cassettes as well, such as "The End of the Israelites." Israeli security forces found dozens of these recordings in the offices of a Hamas-affiliated charity in the West Bank town of Tulkarm, along with cassettes from Saudi Arabia about the Day of Judgement, asserting that the souls of Jews transmigrate after death to the bodies of monkeys and pigs. Israeli authorities detained Jarrar on September 25, 2005, for his involvement in Hamas. 34

Additionally, Jarrar's predictions about 2022 began to appear in mosque sermons in 2001. 35 And finally, the best testament to his impact is that he seems to have influenced the founder of Hamas and its head, Sheikh Ahmad Yassin, who adopted his analysis about the inevitable disappearance of Israel, only with the slightly modified date of 2027. 36

Jarrar might claim that his speculations about the future were not part of the apocalyptic trend because he only wrote about Israel in his book, and not the end of days. But, in an internet chat in Arabic on Islamonline, the website of Sheikh Yusuf Qaradhawi, Jarrar extrapolated further on his vision, predicting the rise of Islam as a superpower—what he calls the "Second Global Islamic Kingdom." 37

Elsewhere he describes how after Muslims recover the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, the Mahdi will arrive and lead them to victory over