Memories

My grandfather, Neuto Everett, used to do a little tin mining, not much, but his real masterpiece was playing music—accordions, violins, he could play any kind of music and he’d always be there to help in sickness if someone wanted any help. He’d always go to find out if they wanted someone to sit up for a night with the sick. There was no hospital on Flinders Island to put them in until later years, when we got the bush nursing sisters and later the hospital. It was never easy for the people on the islands. In that first aid kit there’d only be castor oil, better known as a ‘blue bottle’, a fair number of Aspros, Epsom Salts, and different herbs which they made and used themselves. They always had their Epsom Salts, taken in morning. My mother used to take it at night.

It was always lovely to go for a walk, or watch the moonlight, or the full moon coming up. There always seemed to be plenty of time to study the moon, stars, skies, clouds. Sit on the hill and watch the seas, the gales—to watch the great big seas and in the end there’d be low water—to watch the tides go out and bring up a lot of shells. There doesn’t seem to be the shells there now at Flinders.

When I used to stay at Pinescrub with Johnny Maynard and family he used to ride a white horse home every week from the Five-Mile where he worked. Mrs Johnny would sit on a chair on the verandah looking over the hill and she’d say Johnny’s coming now and I’d say, ‘My word, he’s a long time coming up the road’, and she could see him just coming out of the honeysuckle scrub. That was miles before he got to the main road. But she knew when to put the kettle on to have his meal ready for him. She could always look down to see him coming through this one place. They seem to be able to see a long way away.

We also had a boy with us at Killiecrankie, although he’s dead now, and he could see bullfrogs in the dark. I think they could see in the dark. He’d go and pick up all these bullfrogs and he’d carry them home.

Uncle Bun always seemed to be around when there was trouble. If someone was sick he would come over with fruit from his orchard. Uncle Charlie Jones had a horse called Edna, she was a thoroughbred. Charlie didn’t seem to know how to ride her and many a time she’d throw him, but he was always game enough to go back and get on again. There was one time when he was galloping down the road behind Mr Barry in his ute, who used to bring the children to school. Edna went so fast that she bucked and threw Charlie right into the back of the ute. Mr Barry didn’t know Charlie was there till he got back to the shop.

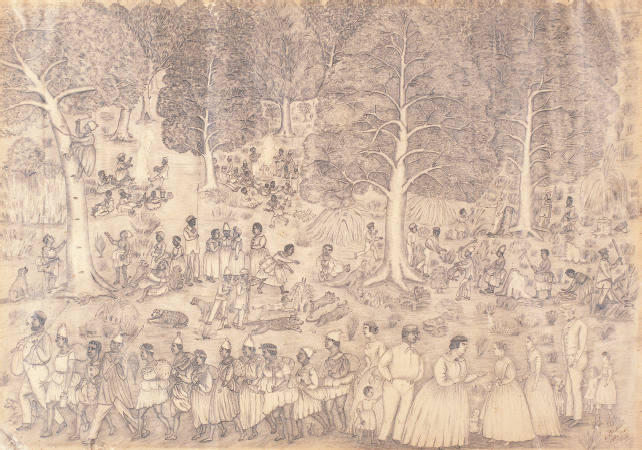

There would be dancing at Pinescrub and all the people from Robertdale would attend. Mum and Dad and the children would walk home again to Robertdale or later across the hills to Killiecrankie. We’d do it all over again because they were better times then than they are today. Mr Dickie Smith used to come to the dances and he’d have the bowyangs on. He always put his knee up before he started the polka, till the player that played the accordion got on the right note, and then he’d put his foot down and around the floor he’d go.

They were all good old-time dancers. Mr Johnny Maynard used to MC the square dances and we had to do them properly, too.

Then we played cricket with a rubber ball and I would bowl underarm. Rounders, too, was our game. We used to practise dancing in the house at Robertdale and we would cut up candles and put them on the floor to make it slippery. This time we thought we’d get some mutton-bird oil, or the dripping down, and put it on the floor. After the first lot we put down we knew we had made one great big mistake, so we got ashes and scrubbing brushes, we scrubbed all the floor out before Mum came home.

Morton Maynard, the carpenter, who built houses for us, went to Chappell Island muttonbirding and was bitten by a snake. They used to say you’d die straight away from fright. Some laughed about it, but Mr Eric Worrell said that with some snakes on Chappell, if you were bitten in the right place you could die on the spot, so that wasn’t very nice.

I can remember when the men folk had finished work at the week-end, they would always be whittling with the pocket knife, making little boats out of wood. They used to make many things. They were always doing something with their hands—whittling wood, making nets, mending nets with shuttles, and plaiting leather. As children we would plait grass tussocks and tie them together across the track. People would fall over them, but we got the stick for doing that. There were many things I can remember doing with the reeds and grass, like making mat rugs and baskets. Today we still have some of our men and women folk who can do whittling and weaving and make many things. We still have to get our knowledge of arts and craft together to pass down the little bits of culture that was given to us by our parents—like shell-necklace making, whittling, weaving and story-telling.

We drank mutton-bird oil. If you drink too much it will come out through your skin, but it’s good for your lungs. It used to be rubbed into our chests when we were children, mixed with some camphorated oil or wild garlic. We had to live the white man’s way, the white women’s way, which hasn’t been any disgrace to us. We had to learn both ways, more so than the whites because we had to live with white people. I only wish I could have learnt more about our own culture.