The wombat lay, full length,

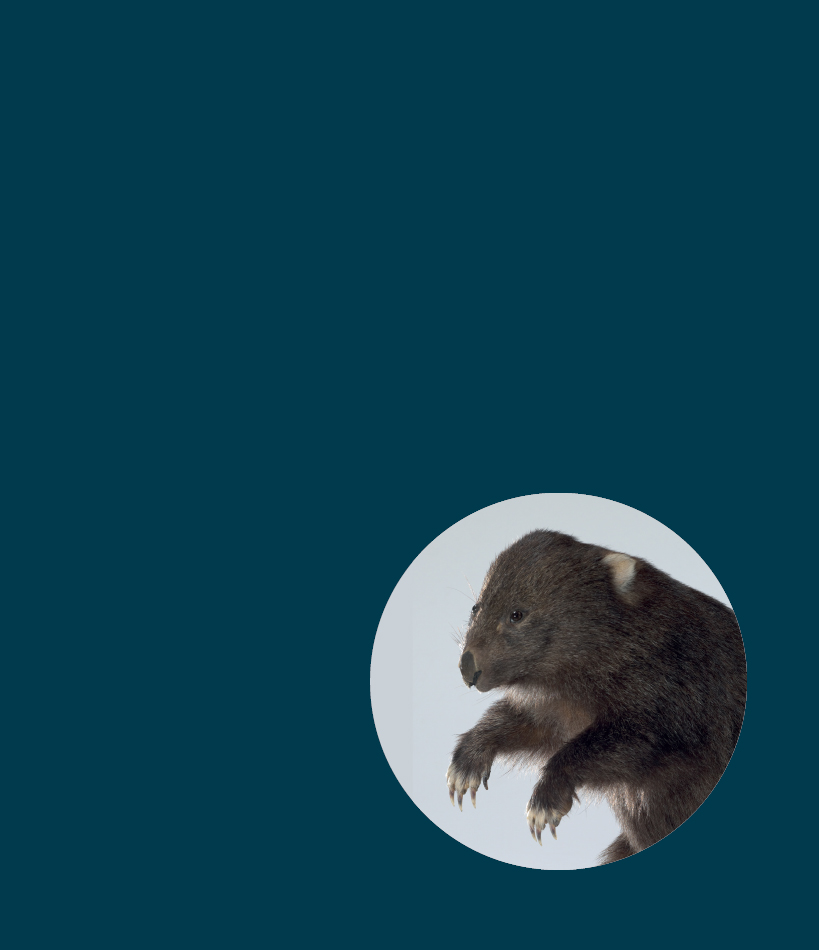

as long as a big dog, but thicker set,

a mass of weight and muscle.

Soft still, his bulk gave but didn’t shift.

It gives me an uneasy feeling

to leave an animal on a road

to flatten into fur and flesh

under so many tyre prints.

You may say that bone dust is all the same—

that morsels for ravens

or worms are neither here nor there

but those meaty silhouettes receding

into ignominious shadows

on the asphalt make me unhappy.

Here, right on the bend,

this dead wombat was a ploy

to catch the outer front wheel

unawares; someone’s wheel

some time in the night

had caught his living self by surprise.

His head was as big as a person’s

and his grey palms big and soft as

a child’s, with lines scored:

the line of fate, the line of the heart.

His fur was not like that of a possum—

even, mink-like to the touch;

his pelt was all manner of hair:

dense brown under-fleece to keep him warm,

marsupial-grey flecked outer fur he shared

with wallaby and bandicoot

for melting into landscapes;

but struck all through in one

inexorable direction from head

to rear like a boar’s or an otter’s,

these needle-thick and pointed-at-the-end

black hairs. They seemed to be

his courage and his will.

His small eyes, his lesser sense,

already dull, evacuated; his nose,

the greater part of his great head.

His claws and shoulders brought to mind

the anecdotes of those who, rearing orphan wombats

in a human house, find, returning home,

the babies have made soft work

of plywood doors and hardwood floors.

In the end, the only way to move his bulk

was to hook an arm under each of his

and haul him like a dead man

off the yellow gravel across the ditch

and leave him on the grass bank

as if in deep repose.

Somehow, his poor back leg,

already gnawed away to the bone

by a devil or a quoll or a dog,

with its missing claw

had tucked itself away out of sight.

There he lies;

the living ants and maggots will do their job:

his fur will fall apart, his mass collapse

from within, his head and claws

and massive shoulders

the last to tie him to his shape and life

as the rest recedes into two dimensions:

an arrangement of bones upon the drying grass,

summer warming up his patch of earth;

the forest ravens jawing higher up the hill,

a magpie carolling each lightening morning

and skylarks overhead

rising on each ascending note.