My brother Ambrose is a tiger hunter.

He is a man beyond the weather, with his breath in the sky and his heart on the track ahead. He walks the contours of the land wearing a cap sewn by his own hand, a jacket the fur worn bare by rough rocks and hungry trees. He stands upon the pinnacles that rise above the ocean of old forest. He looks out upon the sea of a thousand greens, reads a bearing to the next peak and descends beneath the tree cover. Invisible again to human eye, he climbs and strides through the tangled bracken and cutting grass, past moss-covered trunks and fungi-clad logs. Like a swimmer, he comes up for air, emerging a dark creature above the nodding heads of trees high on the next ridge.

No sign. No track. No tiger.

Ambrose lies in the western reaches through winter. He sets up camp in a cave where the walls are painted with black upright figures leaping after kangaroo the colour of dried blood. From the fern-fringed doorway of rock, water seeps and drips a brackish ooze. Above the cave, five solar panels stand sentinel, a clash of form against the shimmering backdrop of wilderness.

In the forest’s underbelly, wallabies tunnel, wombats burrow and tiny quoll rear babies so small four could fit on a five cent coin. A Tasmanian devil wakes at dark and watches pale shards of moon falling through bruised clouds. Its rusted howl scurries across the wind, calling to all who can hear that the Earth belongs not to the tame.

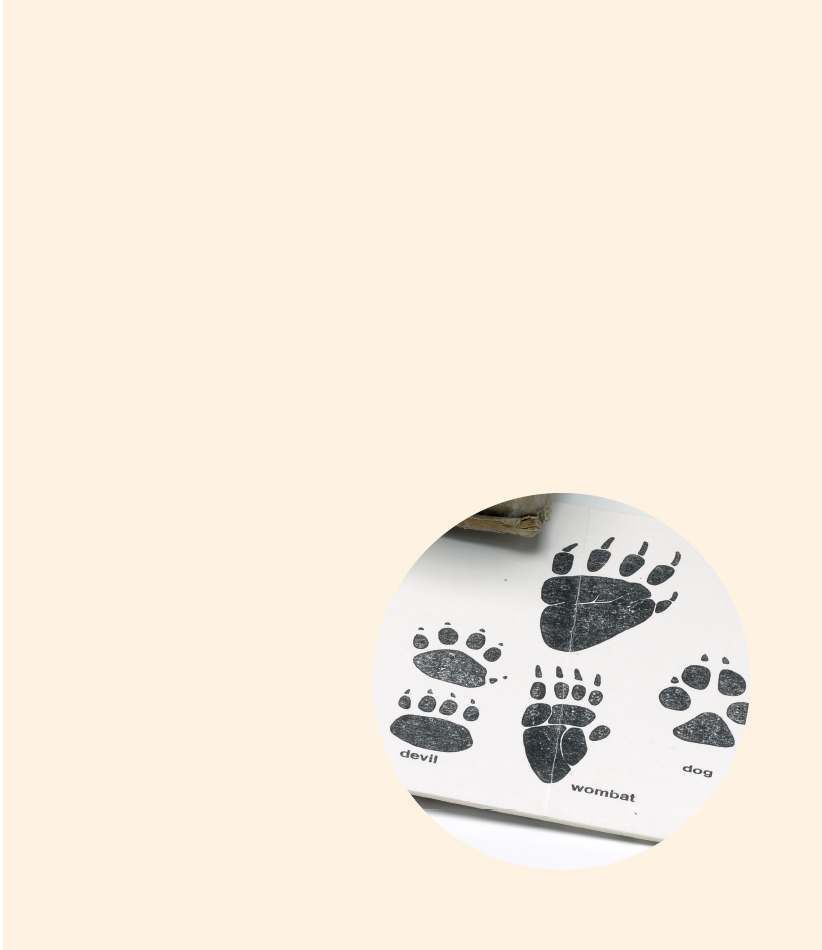

The Tasmanian tiger is striped and carnivorous. It is the largest marsupial in the world and rarer than the snow leopard of Tibet. It has a wide four-toed footprint.

On the far hinterland of forest, more than a hundred kilometres east, where humans have boundaried the wild, parents once said, Never go in the bush at night, never run through the trees after dusk, there are tigers about.

Shotguns were kept close at hand, rumour travelling ahead of the tiger until it was in people’s minds more savage than its Indian namesake.

The last tiger in captivity died in 1937, more than half a century ago. But every year reports filtered in. Some stories made the newspapers, many only got as far as the pub. For more than a decade, Ambrose had been clipping articles from The Globe when they appeared. And he’d kept his ear to the ground. He’d jot down a name overheard from a story in a remote town, and if he thought there was a whiff of truth, he always paid a visit. If a story had created a media stir, he bided his time. He let Parks and Wildlife come in and scour the ground for a week or two. And the Nature Preservation Trust and Friends of the Tiger. Then, when it had all settled down, he’d come by, take a look around and, if he thought it worthwhile, he’d have a quiet word or two with the witness.

The spring just gone, a man out the back of Mount Trial told Ambrose he’d seen a tiger by his water tank less than a fortnight before. Said it had a pup with it. Didn’t care that the whole town was laughing at him. Said it was a bloody tiger all right and no mistaking it. Had stripes. Bloody stripes all down the back of it. Said he heard it yipping at nights back up there behind the house, that yip of theirs unlike any other call in the bush. Said he’d swear on his mother’s grave it was a tiger.

Ambrose always listened carefully to the man or woman as they spoke. He’d smell the air about the farmstead, he’d rest for a while near the spot where the tiger had been seen. Then Ambrose would disappear back into the bush and people would wonder if they’d seen him at all.