Still, still and as still as death lay the Belle, face to heaven, the clear lines of her stretching body cutting the skyline.

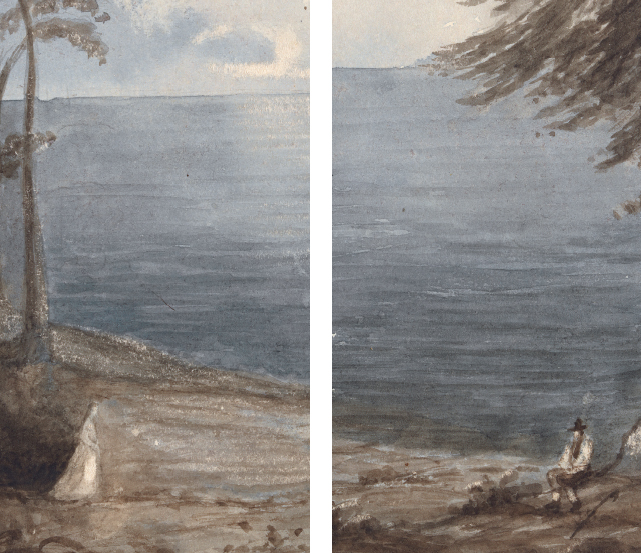

Moonlight flooded the Bay, the air tingled with a white radiance that filled him with a sense of aching oppression; why, in a world so utterly beautiful should death, cruelty, the shadows of evil minds obtrude their malignity? The soft swirl of the water under willow-shaded banks soothed him, willow leaves turned white, water turned to silver under the moon’s magic…black shadows distinct as if cut out of paper, clean cut edges of trees inimitably still in the night, and that enticing rippling sound of ceaselessly running water drew him nearer. He climbed into one of the boats and pushed off, dipping his oars so noiselessly as he guided the bow into mid-stream, that hardly a ripple stirred. Silver water fell away along the sides of his boat; from his seat the world showed through a veil, the whiteness changed to powder blue, a light film of bush fire smoke made the hills swim…Oh, the Heaven-sent beauty of the night, why couldn’t he draw calm from it? Why was it not possible to decide on one course or the other?…

He drew his oars across his knees and let the boat drift on the slow current. So intent had he been on his momentous thoughts that he had not noticed a boat creeping along towards him in the shadow of the willows, but while he rested on his oars the steady dip, dip sounded like the muffled beat of some machine, so rhythmatic was it. He sat listening, drenched in moonlight: he could hear a voice singing, pitched low yet distinct:

‘The deep air silvers

Arc on arc.

The bat is a loosened

Piece of the dark.’

Closer the boat drifted, and he saw the solitary singer. It was Ginny Gilmore. Mrs. Gilmore whom he had looked upon as a tame, staid kind of woman, rather a dear, of course, but not particularly attractive except when she played to him in the winter evenings, well then with the firelight at her back, making a halo-affair of her fair hair, she was rather jolly when she played him his favourites, Chopin’s Seventeenth Prelude and the Londonderry Air. But he had never dreamt that Mrs. Gilmore could indulge so far in romance as to come singing on the Bay in the moonlight. It tickled him and made him forget why he himself was there at midnight. He took a few swift strokes, bringing his boat closer to hers; whistling very softly the plaintive Londonderry Air, he found the two boats rubbing sides under the overhanging trees before she spoke. She said simply: ‘Why come out of your course, Simon?’

‘You don’t seem pleased to see me, or surprised.’ He gave a short laugh, ‘and yet I believe Providence sent you my way.’

‘I’m sure I don’t! If you ever hint that you found me out here I shall gladly kill you…you haven’t seen me; it’s a dream. You understand, Simon?’

He gave a long, low whistle. ‘Then he, Mr. Gilmore, doesn’t know? Golly, how do you manage?’

‘That’s easy enough,’ she dipped her oar impatiently up and down as if longing to be away. ‘We sleep soundly at Hill Farm. We snore. Now let go of my boat.’

‘No, I want to tell you things. I want you to tell me things. Why do you come out here without telling?’

‘Because I should not be here if I did tell. And because I must come or die on a night like this. I stifle, I smother in that close bedroom!…No, no Simon, I haven’t said that, that’s in the dream, too!’ and she shuddered violently, then turning to him asked rapidly:

‘What do you want to tell me? Quick, I haven’t long in this entrancing night.’

‘Shall I stay with the old man, or shall I go on with it all?’ His abruptness brought a smile to her lips. Seen so in the glamour of light filtering through the leaves she made him think of himself grotesquely as Pygmalion. She had taken some enchantment from the night, leaning forward on her oars her clumsy feet were hidden, her white dress might have been of fairy make in the shimmer the moon threw over its silken folds, her eyes were mysterious and beautiful in shadow …Galatea! He put his hand out suddenly and touched her, and before she could answer his first question asked another:

‘Are you real, Ginny Gilmore, are you?’ His question throbbed with a laugh, yet before she could answer to his foolishness he was whistling again that sweet air, so softly the notes fell like fragments of trembling moonlight.

‘Simon, be serious. Of course you are going, if you mean England, Oxford.’

‘But, Ginny (I’m going to call you that tonight, for you’re not the Mrs. Gilmore I know by day), grand is ill, something beastly wrong. I ought to stay here with him. It’s only decent of me to help look after the place.’

‘You’re not going to stay,’ she said with passionate conviction, ‘not for anything on earth must you sink down here into the life of the Bay without going through what your father planned for you’…

In the hush that comes after midnight the voice of the water seemed to rise with Ginny’s voice and urge: ‘You will go, Simon—Simon—Simon.’

He held his oar balanced above the water, letting the silvered drops gather and fall, gather and fall with a tiny trickling sound…

She pointed to the head of the Bay. ‘To-night… and the Belle,’ she whispered. ‘I bring my discontents out here and tell them to her, Simon. She never fails you. Remember. She stands for all wisdom, all tranquillity…all peace.’

The dip of the oars, sound of keels singing through lap of water, of boats floating one up,

one down the river, and, the Belle was left with her languor and her enchantment lying above, crowned with a fillet of moonlight; while below, the Bay, bright and smooth as a mirror, softly rocked the hidden treasure of her secrets and the river bore them out to sea.