• Twenty-Three •

Besides her busy studies at the theater institute, Yomei still did volunteer work with her schoolmates. In the spring of 1944, she was assigned to help in Red Aurora Confectionery factory, which was now mainly manufacturing military rations: canned food, hardtack, soft drink powder, even cigarettes. She went there two days a week. The volunteers were not paid but were allowed to eat their fill in the factory. One of the workshops was still making sweets: taffy, orange drops, hard bonbons, assorted chocolates. The volunteers were allowed to eat as many candies as they wanted, especially the malformed ones, but they mustn’t take any home. On the first day, Yomei was excited to have free candies, but soon she was sated, in spite of her sweet tooth. From the third day on, she didn’t touch the candies anymore. Yet she liked the work there, which enabled her to help the soldiers on the front. The women workers were cheerful and often sang patriotic songs together, and Yomei would join them in their songfests and jot down any lyrics that were new to her.

Lily was fascinated by Yomei’s volunteer work at the confectionery factory and said she wished she could go there once a week so that she could eat so many candies that she wouldn’t have needed the sugar ration anymore. Yomei promised to swipe some sweets for her, though it might be hard, because the candies were also a military ration, and the factory’s rule prohibited anyone from taking them out of its premises. The next time Yomei worked there, she put on a denim jumper skirt with a belt at the waist. When her shift was over, she slipped two pieces of chocolate into the front of her dress in hopes of smuggling them through the front gate. If the guard frisked the leaving workers, she’d loosen her belt beforehand so that the candies could drop to the ground before she reached the gate. Lucky for her, the middle-aged guard recognized her as a volunteer, so with a gappy smile he just waved her through.

Back in the Hotel Lux, Lily was so thrilled to have the chocolates that she ate only half a piece at a time. Yomei said this was the first time she had ever pilfered something, but she was happy to see her friend so beside herself with joy and satisfying her sweet tooth.

She planned to take back candies for Lily more often, regardless of the rule and her unease. Fortunately her volunteer work at the confectionery factory ended a week later, and the students were sent to help dismantle barricades and antitank hedgehogs to facilitate traffic and restore the former cityscape. The Nazi army was in retreat now, and unlikely to come again. Evidently the Soviet and Allied forces would be able to defeat Hitler’s army. From time to time columns of German POWs in tattered uniforms and collapsed boots marched through the streets of Moscow. Some wobbled along on crutches. In silence people watched them pass by, some limping and a few hobbling, all hanging their heads. In spite of their anger, the spectators never turned violent. At most, a few babushkas spat at them. Now, even the few Chinese expats in the capital grew restless, and some started talking about going back to China to fight the Japanese invaders and also to found a new country.

As the war continued, with one victory after another, food supplies improved considerably in Moscow in 1944. Late that year, there were even U.S. cans for sale in some stores—Spam, tuna, corned beef, luncheon loaf, beans and peas, beef stew, sardines. Both Yomei and Lily could see that the final defeat of fascism was on the horizon. Though their life had become somewhat normal now, they were busier than before. As the war seemed to be winding down, more Chinese youngsters from the children’s home in Ivanovo were coming to Moscow for college. To facilitate school admissions, they were supposed to get naturalized, and some of them became Soviet citizens. Yomei and Lily often went to the railway station to receive the girls. A number of boys got into Bauman Moscow State Technical University, but they had friends in the city and didn’t need Yomei and Lily to help them. Among the girls they received were Lily’s younger sister Linlin, Oyang Fei, Zhang Maya, and others. Maya’s mother was Zhang Ch’in-ch’iu, the highest-ranking female officer in the Chinese Red Army, who used to be the only woman commander of a division. Unlike the others, Oyang Fei, nicknamed Feifei, was an orphan and had no idea who her parents had been. It was only known that she had been saved and brought over to be raised in the Soviet Union after her parents had been killed in the mid-1920s by the Nationalists. Yomei and Lily did their best to accommodate the girls and also showed them around a little.

But when it got cold, they couldn’t receive others as before, because they no longer had their own room in the Hotel Lux. To save fuel, half of the houses and buildings in Moscow were shut down—people had to share heated rooms with others in the winter. Yomei and Lily’s room was closed, so they’d have to stay with others. Unexpectedly, Ryo Nosaka, a short, plump woman who was the wife of Sanzo Nosaka, the president of the Japanese Communist Party, noticed the two young Chinese women’s predicament. Ryo and her adopted daughter were living in a heated suite on the third floor of the Hotel Lux, so she invited Yomei and Lily to stay with her family, telling Yomei that her father Zhou Enlai was a good friend of her husband’s. “Your father is so handsome, like a movie star,” Ryo once told Yomei. Yomei replied, “Yes, that was why I have him as my dad.” Both Mrs. Nosaka and Lily laughed. Ryo said it should be the other way around because a child couldn’t choose its parents.

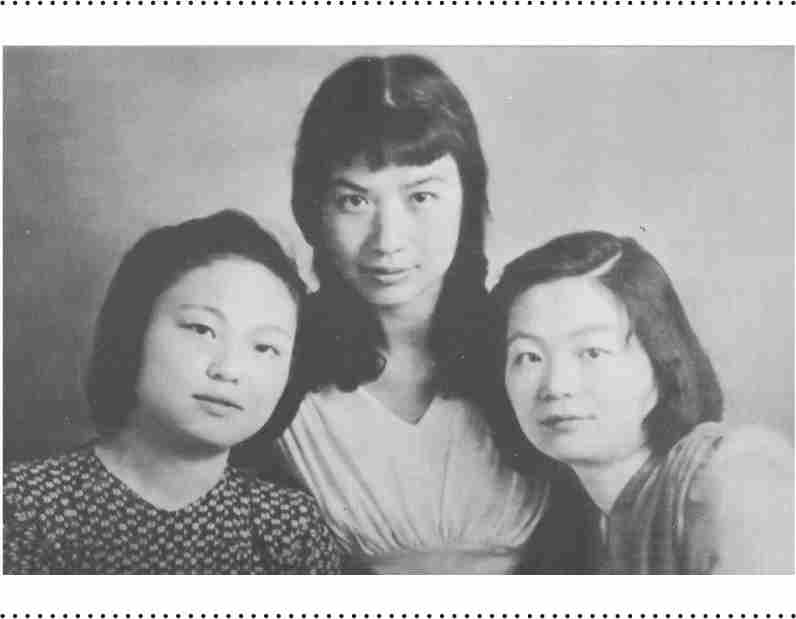

Linlin, Yomei, and Lily in Moscow, July 1945

Yomei happened to know something about Nosaka, who was in Yan’an now and who had been close to the top CCP leaders. Under the Comintern’s order four years before, he had gone there to help the Chinese people fight the Japanese invasion, supervising a small institute of Japan studies in Yan’an. His staff combed newspapers and magazines published in both Japan and China, followed the radio broadcasts, and analyzed the information they gathered. Thanks to Nosaka’s dedication, Yan’an’s intelligence work on Japan and its military was brought up to date. In the red base he began to publish in Chinese as well, using the pen name Lin Zhe. As Otto Braun had, he asked for a female companion, and the CCP assigned a pretty young woman named Zhuang Tao to be his partner. Yomei shared what she’d heard about Sanzo Nosaka with Lily, saying that Ryo might have been abandoned by her husband, though the woman often bragged that she and Sanzo had been married for two decades. On the other hand, Yomei felt that Ryo may have known the true situation of her marriage and accepted her husband’s cohabitation with a young Chinese woman as a fait accompli—like most Communists would under such circumstances. Every Party member had to sacrifice their personal interests for the revolutionary cause, so even Ryo’s marital trouble might be due to the kind of arrangement made by the former Comintern. In spite of their unease, Yomei and Lily were pleased to have a warm room in the Japanese woman’s suite.

Soon after they had moved in with Ryo, she asked them to fetch lunch for her because she couldn’t leave her small girl alone in the flat and the cafeteria was too far away, in the basement. Yomei and Lily agreed to get lunch for her, since Ryo would let them keep the soup served for her at the meal. The two would alternate running the errand, but as it wasn’t easy to climb with a plate and a bowl full of soup up all the way from the dining hall to Ryo’s suite, they just ate the soup in the cafeteria before bringing back lunch. Often they complained between themselves that Ryo was too stingy to let them have any solid food. For her work at the broadcasting station, Lily got one meal ticket a day, but Ryo, even though not working, received two meal tickets every day. More unfair was that she ate much better food. Living in the same suite with her, Yomei and Lily saw what mother and daughter would eat at breakfast: white bread, hard butter, sour cream, raspberry jam, cheese, fried peanuts, bologna, ham, preserved fruit; some of those items had been hard for common people to come by even before the war. More amazing, Ryo would drink coffee and tea with honey and creamer every morning. Small wonder the woman didn’t need the soup served at lunch—she already got enough nutrition from other foods.

More outrageous was that they soon discovered that Ryo had foodstuffs stashed away deep in a closet, which Yomei called “the little granary.” In there were stacked bags of rice, millet, cornmeal, wheat flour, peas, and soybeans, some already moldy and wormy. In private, Yomei and Lily often sighed, saying that was “a lifetime’s supply of food,” and they complained that while most people were starving, here so much stuff was uneaten in the closet and might be consumed only by worms and mice! Even though they knew this was a rare case, they couldn’t stop griping between themselves. Yet despite their unease about Ryo Nosaka, they both admitted that the woman was composed and good-natured, always treating the child like her own. Even though she must know her husband was living with a pretty young woman in Yan’an, she looked untroubled and even serene. She was an experienced Communist, and together with her husband had been to different parts of the world, including the United States, about which she often talked to Yomei and Lily. She said America was a wild country, with little civilization except for New York City and San Francisco, but its environment was pristine, the air so clean that you didn’t need to shine your shoes for months. She often sucked her teeth when speaking, as if having a toothache. Her chubby face and bespectacled eyes plus her shiny, severe bun made her appear like a professional woman, an office lady. Ryo had met Zhou Enlai several times and told Yomei that she admired her father. “Such a nice man,” she’d say, her eyes turning dreamy.

When it was getting warm, Yomei and Lily returned to their former room on the fourth floor and didn’t use Ryo’s lunch soup anymore. At long last, in early May the news of German surrender came, and many people, especially foreigners in Moscow, took to the streets to celebrate, singing and dancing with abandon, though most Russians remained quiet and looked sober and grim, perhaps because the weight of victory lay heavy on their minds. So many families had lost their loved ones in the war that they couldn’t take the great news with the jubilation of triumph now.

Soon, many Chinese expats stranded in Central Asia returned to Moscow. They had failed to cross the Mongolian border to get back to northern China, and now they hoped they could find another way to return, either through Kazakhstan and Xinjiang or through the Trans-Siberian Railway network. But first they had to come back to Moscow to get official approval and papers. For months, Yomei and Lily were busy receiving expats who resurfaced in the capital. Among the returnees were those officers who had studied at the KUTV and who were known to Yomei and Lily. First came Li Tianyou, a handsome young officer with a ramrod bearing who used to command a division under Lin Biao. Li had begun to attend the Frunze Military Academy in the fall of 1938. When Lin Biao was returning to Yan’an from Moscow at the beginning of 1941, Li left too, but he couldn’t take the same route through Almaty and Tihwa that his superior was taking. Instead, he left with some expats for Central Asia in hopes of crossing the Sino-Mongolian border. But like the others, he got stuck in Siberia and couldn’t move around. His return to China was smoother than that of the others, partly because he came back to Moscow earlier than they did—at the end of 1944. He set out for Kazakhstan right away. Before he left, Yomei and Lily treated him to lunch at the broadcasting station’s cafeteria. Known as the Tiger General, he was expected to return to Yan’an as soon as possible. Now that the war in Russia was finally over, he had to depart without delay. He said he’d tell Lin Biao that he had met Yomei in Moscow again and that she was prettier than before. She was about to say that Lin Biao had a new wife now, that Li Tianyou shouldn’t bring her, Yomei, up in conversation, but she thought better of it.

A few months later their friend Grandpa, Yang Zhicheng, came back to Moscow too, wearing a squashed felt hat as if it were still winter. In spite of the sobriquet given him by naughty Yomei, Yang was still not that old, only forty-one, but he was so famished that he was scraggy and a little bent, hardly able to walk steadily. He arrived at the Hotel Lux and told the front desk that he wanted to see Sun Yomei and Lin Lily. At first, the two women didn’t recognize him due to his emaciated, misshapen face. Then Yomei cried out, “Yang Zhicheng, Grandpa, why are you here?”

“Didn’t you go back to China?” added Lily.

He explained that he’d gotten stranded in Siberia and couldn’t get across to Inner Mongolia. Yomei realized he must be hungry and had to eat at once, so she and Lily told him to wait for them in the lobby and they’d be back in a moment. They rushed up to their room to get their meal tickets. But when they came down again, Grandpa was gone. So they went out in search of him. Yomei was worried, knowing he had no place to stay. Her plan was to let him eat something first, then find a bed for him, but why wouldn’t he just wait for them? He must have assumed that the two women were unable to help him, or maybe he thought that he didn’t want to be a burden to them. They shouldn’t have both gone back for the meal tickets, leaving him alone at the front desk. Now they had to find him.

Lily found Grandpa at a tram stop and brought him back. Yomei blamed him for running away like that. They took him to the hotel’s cafeteria, where Yomei bought a plate of fish soup for him. He began to wolf down a hunk of kringle, together with soup made of burbot and crushed tomatoes. He was eating so fast that he bit his tongue, which bled a little. “Gosh,” Yomei said, “don’t rush, don’t eat your own tongue!”

He grinned and nodded his shock of tousled hair. Lily went away with a mug to get some hot tea for him.

While munching on another piece of bread, he kept saying he must find a way back to join Commander Lin Biao’s army in Manchuria. Once he had some food in his stomach, he grew more alive. He said the two women friends looked prettier than before, more like foreign ladies now. He even asked Yomei whether she was still carrying on with General Lin Biao. To that, Yomei just answered, “He wrote me a year and a half ago and told me that he married a young woman in Yan’an. They might have a baby now.”

“Oh, that’s too bad,” Grandpa said with a shrewd twinkle in his eyes. “That wasn’t like him. He should’ve had more patience with a beautiful girl like you.”

Yomei clapped him on the shoulder and said, “Shut up! We’ll have to find a bed for you somewhere.”

They went to see Igor, the superintendent in the Hotel Lux who was employed by the IRA, and asked him to help.

Igor was a squat man in his midthirties, with a large head and a toothbrush mustache. He was fond of the two young women and often asked if he could do something for them. To Yomei’s amazement, Grandpa could speak Russian with ease now. He and Igor chatted about the Lake Baikal region, which Igor was familiar with, having grown up in Siberia. How he missed ice fishing on the lake, he told them. He assigned Grandpa a room just for himself. Yomei and Lily were delighted and told Zhicheng that they could find more food for him.

When Yomei had free time, she’d go see Grandpa and chat with him over tea. Sometimes Zhicheng would get carried away while talking to Yomei, whom he took as a close friend. Once he mentioned something that disturbed her. He said one and a half years back, in December 1943, there’d been a conference among the top CCP leaders in Yan’an. Chairman Mao presided over the meeting and demanded that every attendee do self-criticism so as to reform themselves properly. Somehow Mao singled out Zhou Enlai and asked him to confess his misdeeds in front of everyone. Zhou was so flabbergasted that he sank to his knees and apologized to Mao while blaming himself for not always having taken Mao’s side in the past struggles within the Party. Grandpa described the incident to Yomei vividly. At the beginning of the conference, Chairman Mao had announced to the audience what he was doing by using the analogy of taking a bath: “This rectification effort is to make some Party members undress and drop their trousers to show their bodies. Then with the help of your comrades, you can wash yourself clean, and some will help you scrub your backs. Once you get cleaned, you will feel comfortable again, like a sick person who has recuperated.” Mao concluded by declaring, “Now is Zhou Enlai’s turn. Please undress yourself and drop your trousers.” To everyone’s astonishment, Zhou dropped to his knees instead and said, “I admit my crimes, I admit my crimes, Chairman.” Mao was startled and cried sharply, “Why are you doing this? This is like calling me names, as if I were an emperor.” Zhou replied, “Chairman, you’re the emperor of China’s revolution. Both Comrade Liu Shaoqi and I agree about this—you’re our emperor. Without you at the helm, our ship would capsize.”

“That might be just hearsay!” Yomei said crossly.

“Anyhow,” Grandpa went on, “you shouldn’t take this to be merely a rumor. We all know that on the Long March Zhou Enlai at times washed Chairman Mao’s sore feet. That was his way of showing his love and reverence for our great leader.”

Yomei knew that Father Zhou had opposed Mao several times in the past decades, but she didn’t believe what Grandpa had told her. That must be a malicious rumor or slander. She demanded to know the source of this hearsay. Hard as she tried, Grandpa wouldn’t reveal anything more and just said he’d heard about the incident from someone who was at the conference. He shook his head and kept giggling.

In spite of Yomei’s disbelief, the rumor did throw a shadow on her mind, and for weeks she couldn’t shake off the image of Father Zhou kneeling in front of Chairman Mao at a meeting, calling him “Emperor” and begging for mercy.

Early that summer came Zhong Chibing, who had been a comrade in arms of Grandpa’s, so Igor allowed them to share the same room in the Hotel Lux. The superintendent was so generous that he gave them each a meal ticket for dinner in the cafeteria. They could eat there six times a week. That solved the problem of their board. Like Li Tianyou and Yang Zhicheng, Zhong was also a remarkable officer, but he looked more like a scholar—he wore horn-rimmed glasses and had lost his right leg and left thumb after being wounded in battles back in China. With a single leg, he had managed to complete the nine-thousand-mile trek (the Long March) and become a legendary figure in the Red Army. Then, in the summer of 1938, he was sent to the Soviet Union to get medical treatment and to study. The Russian doctors operated on the stump of his right leg and stopped it from getting infected again. (He had undergone three operations back in Yan’an, treated intermittently by the Canadian surgeon Dr. Norman Bethune, but the infection couldn’t be checked. As a consequence, he’d lost the entire leg.) Then he attended the Frunze Military Academy together with Grandpa and Li Tianyou, and they all graduated at the same time in the summer of 1941 when the Germans started the blitzkrieg on the Soviet Union. But Zhong Chibing was particularly close to Liu Yalou, Yomei’s other passionate suitor among the expat officers. Together with Yalou, Chibing went to Central Asia, but Yalou was recruited by the Soviet Eighty-Eighth Infantry Brigade in Khabarovsk and was still serving there as a colonel. Chibing revealed to Yomei that his friend Liu Yalou had often mentioned her, saying that the only woman who could possess his heart was Sun Yomei. Evidently he hadn’t given up on her, so she’d better be prepared for that man to pop up in her life again, given that the war was over and he might leave the Soviet army. Yomei begged him, “Please, don’t deputize your buddy like this! Liu Yalou is already a family man.”

Liu Yalou, Yomei’s passionate suitor, in the Frunze Military Academy, 1940

Liu and Zhong would remain close friends indeed. In the following decade Liu Yalou and Zhong Chibing would still work as a pair, Liu in charge of China’s air force and Zhong running the country’s civil aviation.

Those officers who resurfaced in Moscow would play significant roles in the CCP’s military. Soon after the establishment of the PRC in 1949, Li Tianyou and Yang Zhicheng became three-star generals, though Zhong Chibing was given two stars, probably because his work focused more on the civil services by then.

Left to right: Yang Zhicheng (“Grandpa”), Yomei, Li Tianyou, Lily, and Lu Dongsheng, who was also a general educated and trained in the Soviet Union