• Fifty-Five •

Both Lily and Lisa saw Uncle Vanya and wrote to congratulate Yomei on such a splendid production.

After Yomei and Jin Shan went back to living together, Lily stopped coming to visit, partly because she and Shan didn’t like each other. Perhaps she resented the fact that Yomei had never consulted her when she had decided to marry him. Now, she had once again ignored Lily’s admonitions and would not divorce him, as if to show that her love for this man had no bounds. As a result, Lily and Yomei could no longer remain as close as before, though they still saw each other a couple of times a year.

In her letter, Lisa said she and two other Soviet women, Yomei’s peripheral friends—Eva and Grania—had attended the play together, and they all had loved it. Yomei had known Grania for years; her husband Chen Changhao, Professor Chen, had flown to the Soviet Union on the same plane with Yomei in 1939. He had gone there for medical treatment for his gastric ulcer but later got stranded in the USSR during the war, where he worked in coal mines and also served in the Red Army. He then married a young Russian girl, Grania, who was illiterate at the time, having completed only the first year of elementary school. Lily and Yomei used to joke about the Soviet propaganda that claimed that the USSR had eliminated illiteracy, but Grania could hardly read. After coming to China with her husband in 1951, she had begun to acquire some literacy. She was a stout blonde now, working as a typist at the translation bureau together with Lily. As for the other Soviet woman in Beijing, Eva Sanber, she was quite extraordinary. She was a German Jew who, while working at the Comintern in 1934, fell in love with a Chinese poet, Hsiao San, who was fifteen years her senior. Hiao had been Mao Zedong’s classmate back in their hometown in Hunan Province. The poetry he wrote was mediocre because he believed that poems should serve like knives and bullets in fighting capitalist oppression. Having lived in Europe for decades, he knew several languages and became an accomplished translator. In order to marry him in Moscow, Eva had to become a Soviet citizen first, or she wouldn’t be able to live in the USSR, so she renounced her German citizenship and was naturalized. She lived in Yan’an for some years in the early 1940s. At the time, Yomei was studying in Moscow, though she had heard of the woman who was teaching photography at the Lu Hsun Academy of Literature and Arts in Yan’an. Not until 1952 did she meet Eva in person for the first time, at Lisa’s home. Now, she was pleased by the three Soviet women’s compliments on Uncle Vanya. Lisa even said it was “a triumph.”

Thanks to the success of the play, Yomei received a job offer from the Central Academy of Drama. They wanted her to head the program for training stage directors and to teach the Stanislavski method, which had been universally accepted in China after the production of Uncle Vanya. The students were mostly young dramaturges from all over the country. By virtue of her Russian skills, Yomei could also assist the Soviet theater experts teaching at the academy. She sensed this might be a great opportunity for her to develop and disseminate the art of directing, since the students were rising powers in provincial theater circles and would form the base of China’s spoken drama.

What’s more, Jin Shan no longer had a position at the Youth Art Theater, which had treated him harshly and stripped him of his official position and wouldn’t assign him a new job. It was time for Yomei to leave the theater. Although officially she was still the director in chief there, she wouldn’t give as much time and energy to the Youth Art Theater as before.

Soon Jin Shan and Yomei moved out of the theater’s dorm building. They moved into a courtyard with a red front gate off Zhang Zizhong Road in which several theater artists’ families resided. The enclosure was at 3 Iron Lion Alley, and at that address lived Oyang Yuchien, the master dramaturge, Cao Yu, the famous playwright, and Sha Kefu, a writer and translator who was head of the Central Academy of Drama. Yomei and Jin Shan had bought a portion of a house—four rooms—for themselves, but they were reluctant to mix with others—their neighbors were all either celebrities or officials. Shan and Yomei had a wall built to block their tiny front yard so that they could have their own entrance at the back. Life was peaceful for them now. During the day, Yomei went to work at the Central Academy of Drama, and Jin Shan, though still carrying the baggage of political problems and still without a work unit, would participate in play or movie productions on his own—usually he was given a role or asked to direct a project for a theater or a film studio. The embezzlement accusations against him were dismissed, since he hadn’t pocketed any of the Party’s funds and had returned the gold bars as soon as the acquisition of the equipment for the radio station had fallen through. But he was a non-Party person now, more like a freelance artist—such a state of life could be frightening in the new society, where everyone had to have a work unit to be a respectable citizen. Yet he took such insecurity in stride and even mocked himself as “a free soul.”

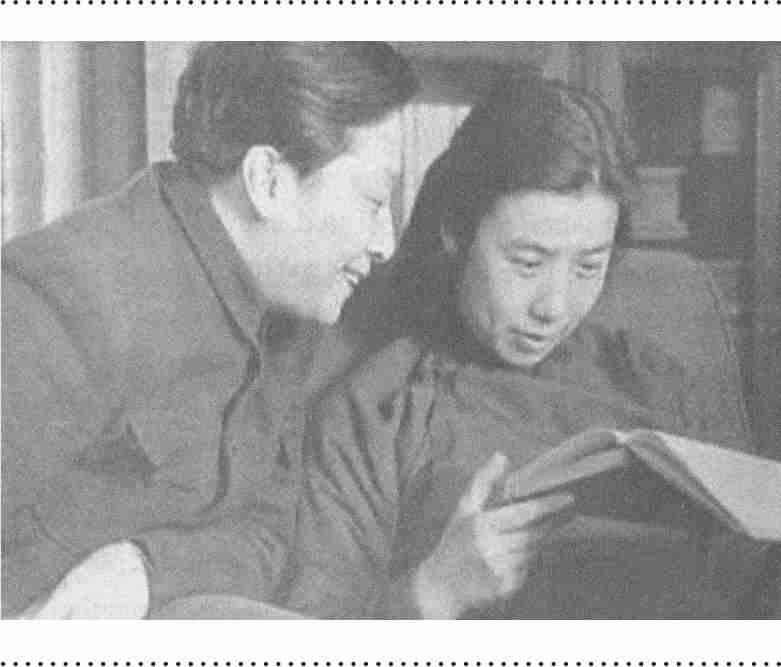

Jin Shan and Yomei

Although Premier Zhou seemed to have forgiven Jin Shan after his successful performance in Uncle Vanya, Shan wouldn’t go to the Zhous with Yomei anymore. Father Zhou once asked her, “Where’s Jin Shan? I haven’t seen him for almost half a year.”

“He’s too ashamed to come and face you,” said Yomei.

The premier chuckled. “He ought to turn the page. What has he been doing these days?”

“He’s been directing a movie called The Chrysanthemum Mountain.”

“Which studio is making it?”

“The Central Documentary Studio. It’s a good movie, and he’s quite passionate about it.”

“Tell him to come see us when he’s free.”

“I’ll let him know, Dad.”

Even though she passed Father Zhou’s invitation on to Jin Shan, he still felt uncomfortable going to the Zhongnanhai compound. At the Zhous’, by custom he’d have to call the couple Father and Mother. It was awkward, so only on holidays did he go with his wife to visit her adoptive parents. Whenever possible, he stayed home. Even when Yomei’s friends and students came to visit, he avoided them, shutting himself up in his study. He knew that his misdeed had harmed his wife’s career as well, because their superiors didn’t like her way of keeping their marriage intact, which had contradicted the Party’s principles. As a consequence, they didn’t trust her anymore, even though they couldn’t punish her overtly. Now that he held no official position, what he cared about was their family—so long as Yomei stayed with him, he didn’t give a damn about what others thought of him.

By now Yomei’s aunt Jun had moved to Tianjin, where her husband Yida had a new job in charge of the propaganda work for the city’s labor union. But the couple often came to the capital. Whenever they were in Beijing, they would come to see Yomei and Jin Shan, for whom they’d bring a carton of Great Gate cigarettes. In the beginning Jin Shan didn’t stay with them for long when they were there, but Yomei kept telling him to stay around. By and by, Jun and Yida began to get along with Jin Shan, treating him with the ease and warmth they had before. They still respected him. Yida, who was eight years younger than Shan, often joked, “By our family tree, you should call me Sixth Uncle.” That Jin Shan would never do, but they had become good friends. Because Yomei called Jun “Sixth Aunt,” Jin Shan did the same, even though he was nine years older than she was. Oddly, he didn’t feel embarrassed at all when calling her that. As for Yida, Jin Shan treated him more like a younger brother.

Among his friends and acquaintances, Jin Shan was known for his excellent cooking. When Jun and Yida were there, he’d make his signature dishes for the couple. Jun would tease as the meaty aroma wafted into her nose, “Mmmm, I wish we could come more often. We sure miss your cooking.”

Yomei gave a hearty laugh and told her, “Then you should come every other weekend.”

One Sunday afternoon in the fall, to Yomei’s ecstatic surprise, Lily came. Like everybody else at the time, she just popped by without giving a heads-up. Yomei put away the Goldoni play she had been translating. The two friends sat in the living room and drank Iron Goddess tea while Jin Shan stayed in his study. Lily didn’t look happy, because she had often been pulled away from her work at the translation bureau. She was one of the translators rendering Mao’s writings into Russian, which she viewed as her most important work for now. There were two Russians at the project too, but their Chinese was limited, so Lily’s help was essential and integrated with the Russian experts’ efforts. Yet in recent years Jiang Ching had often called her away, saying Lily was indispensable to her. Whenever Ching made such a request, the leaders of the translation bureau had no option but to let her go. Lily couldn’t help but believe that Ching was a hypochondriac who relished endless medical attention.

Just last year, Jiang Ching had stayed in a sanatorium called Liu Village on West Lake in Hangzhou city. She even had her private yacht there. Probably because she was tired of being alone, since Mao couldn’t stay with her the whole time in Hangzhou, she approached Lily’s boss in Beijing, Shi Zhe, and asked him to send Lily down to Liu Village to keep her company. Lily was unhappy about such an interruption, but had to go. The good news was that at Liu Village she had run into their mutual friend Yang Zhicheng, Grandpa. He was the vice president of the University of Military Affairs and a three-star general now, but he was in such poor health that he could hardly do any real work at his office. Grandpa and his wife were rapturous to meet Lily at the sanatorium. Zhicheng told Lily that he was elated to see Yomei’s directorial career soaring. He reminisced about their old days in the Soviet Union with a lot of feeling, telling his wife that it was Lily and Yomei who had saved his life, helping him with bed and board when he returned to Moscow from Central Asia. “I was skin and bones, so famished that I almost ate my own tongue when they bought me a bowl of fish soup and warm bread in the hotel’s cafeteria,” he said, his eyes teary, then laughing.

Lily told Yomei, “Evidently Grandpa and his wife are big fans of yours, but somehow Jiang Ching didn’t like you anymore. She once said to me, ‘Yomei, that young girl, gives herself such hoity-toity airs now.’ She seemed irked by something.”

“She still treats us like teenagers,” Yomei said. “She has approached me a couple of times and wanted me to collaborate with her.”

“On what?” Lily’s face was a little haggard, her bold eyes glowing while their lids flickered.

“I’m not sure of the specifics. She said together she and I could revolutionize China’s theater. But she and I are not in the same boat—she’s in pursuit of power, while I’m in pursuit of art and beauty, so it’s like we belong to different species. If we’ve taken different roads, our paths mustn’t cross.”

“Ching’s crazy and should stick with photography. She’s a fine photographer, you know.”

“I saw her work at an exhibition. She has her touches, but she wants to branch out into theater now.”

“She tried hard to make me stay with her and even allowed me to use her yacht to visit some little islands and waterside villages. By the way, your reunion with your husband also gave Yeh Qun some relief, I guess.”

“Why? Why would she feel relieved?”

“Last winter Lin Biao and Yeh Qun went to see Jiang Ching in Liu Village. I was with her when they arrived. I sat with them for only two or three minutes and then went out of the room, because Lin Biao was a major leader and might have important business to discuss with the First Lady. I just didn’t want to be in their way. But when I went back two hours later, Ching blamed me for leaving her alone with the Lins. Yeh Qun had sobbed and claimed that I was rude to her because I was your close friend, and still bore her a grudge. That was insane, wasn’t it?”

Lin Biao and his wife, Yeh Qun

“Hysterical. How did Ching take it?”

“I told Ching that I’d left purely out of politeness and respect. Lin Biao was a top military leader and Yeh Qun had been his wife for many years. How could she still feel insecure, threatened by you? She’s a psychopath and worked herself into a fury for no reason.”

“Did you say that to Ching?”

“Yes. Ching smirked and said, ‘That means Lin Biao hasn’t forgotten Yomei and may often have brought her up in front of his wife. Fortunately, Yomei and Jin Shan are back together, or else more trouble would start in the upper echelons.’ I said to her, ‘You know, Yomei is quite modest about herself, not interested in politics or power. She just loves the theater.’ Ching snapped, ‘The arts are always part of politics. The notion of artistic purity is totally bourgeois. In any case, if you see Yomei, tell her I’m pleased about her decision to preserve her marriage.’ ”

“What did she mean?” Yomei asked in genuine perplexity.

“To some men in the highest circles, your divorce would mean you were finally available, which might mean that more marriages might fall apart.”

“Heavens, we’re in such a manic world!”

“Just be careful about Yeh Qun and Jiang Ching. They are unbalanced and can do lots of damage.”

“You should be careful about Ching too. Don’t get too close to her. So many people despise her.”

“I’m aware of that.”

They also talked about the young man Lily had been seeing. He was an officer in the Ministry of Defense, but Lily felt that their relationship might not go anywhere, because he kept asking her for presents, particularly for things from abroad—kidskin gloves, a gilded fountain pen, a Swiss army knife, a pair of oxfords, what have you. She confessed she was no longer interested in men, much like Oyang Fei had, who had quit dating altogether, using the excuse that she couldn’t understand the accented Chinese some men spoke. Both Feifei and Lily must have been deformed by their Soviet education, making them unable to fit in the new society here. In the eyes of many Chinese, they resembled foreign girls, wearing shoulder-length permed hair and blouses and skorts in the summer and woolen overcoats and even stockings in the winter (as if to show off their legs), whereas their women colleagues just wore thick padded pants. Some called them “foreign dolls” behind their backs, insinuating that they were out of touch with life in China. They were hard to please and always opinionated, tactless and outspoken to the point of being ludicrous. Even regular Chinese sodas and street food would upset their stomachs. They couldn’t help but adopt superior airs. On top of that, they sometimes offended or embarrassed others unawares. At meetings, they talked at length as if they’d been in charge, and worse, their views were mostly impractical, coming only from books. They were like delicate flowers cultivated in a greenhouse, unable to survive the elements. If you married a woman like these “foreign dolls,” you might never have peace at home.

Yomei sensed her friends’ plight and said that Lily and Feifei must do their best to readapt themselves and think and behave more Chinese. But she amended, “Still you mustn’t lose your innocence, your purity of mind and spirit. You must live your own life, even if you can’t find a real companion.”

“Bah,” Lily grunted, “I don’t need a man. Men disgust me. To tell you the truth, I feel safer and more comfortable when mixing with women.”

“Actually, some women can be vicious and dangerous too.”

“Name one for me.”

Yomei did a double take. Though she thought of mentioning Jiang Ching, she checked the impulse, since Lily and Ching seemed to get along. Yomei realized that her friend might still be traumatized from seeing a man throw a woman into the ocean when she was a little girl on a steamer. Or maybe Lily was just frustrated by the fact she’d never gone with a man she could love wholeheartedly. What was wrong with her? Feifei had the same problem, even though she did get on well with her male colleagues. Their Soviet years seemed to have shaped their personality and mentality. It stood to reason that people viewed them like a different species. But Yomei knew they actually preferred a certain kind of man, someone like Wang Jia-hsiang, the CCP’s former ambassador to the USSR, who was a revolutionary as well as a scholar, erudite and perspicacious and capable of solving hard problems, and who knew both Russian and English. She remembered that Lily had once quipped, “If only there were a younger version of Ambassador Wang in China! I would chase such a man to the ends of the earth!” Yomei had responded, “There must be some unpolished young fellow unnoticed by you yet. So keep your eyes peeled, and find a young man full of potential and turn him into a piece of polished jade, even though he might still look crude at the moment. A good relationship should make the two persons better than their former selves.”

“You speak like a great educator.” Lily clapped her on the shoulder.

“Young women often complain there aren’t enough good men around, but most good men are products made by good women. We must try to improve them.”

“So I must find a diamond in the rough?” Lily smiled, batting her eyes.

“Yes, that should be a goal. Keep in mind, no one is polished naturally.”

Deep down, Yomei was glad she was different from her friends who had been educated in the Soviet Union and that she was fond of men, particularly a man like Jin Shan, with an artistic bent, articulate and percipient. She realized she may have meant to make him a better man all along, as if she were also a director of the domestic life.

Yet she and Lily both agreed to avoid any entanglement with the Party’s politics. Life was short, and there must be more meaningful and enjoyable things to do. Lily firmly believed that a woman’s happiness mustn’t depend on a man in her life. That Yomei couldn’t refute. When the rain had eased off, the sky brightening up, she helped Lily into her khaki windbreaker and told her to notify her before she came next time, so that she and Jin Shan could prepare a good meal for her.

“I just want to see you,” Lily said, tying her hair in a violet bandanna. She stepped out into the damp, chilly wind, cradling an oilskin umbrella in her arm.