• Sixty-One •

The Chinese translation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in 1901. The two translators, Lin Shu and Wei Yi, described the process of their translating Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel as follows: “We two wept then translated, and translated then wept, lamenting not only black people’s bitter life, but also our four hundred million yellow people who will become miserable successors to blacks. Furthermore, yellow people’s calamity will not be long before it strikes. There is already a ban on Chinese workers in North America, and our compatriots are mistreated in many countries—these facts indicate that we are not that different from black people, and actually we might be in a worse situation. From their erstwhile suffering as slaves we can imagine our future. We are becoming yellow niggers.”

Lin Shu was a famous translator and translated more than two hundred novels and plays, from Tolstoy to Shakespeare. But in point of fact, he didn’t know any foreign words. He collaborated with others who could read English, French, Russian, and Spanish, and those who could explain the stories to him. They team-translated, paragraph by paragraph. Lin Shu was such a lively, rapid writer that he declared that the moment his partner finished explaining a paragraph, he had already put it on paper. In spite of numerous imprecisions, every title he rendered was embraced by the public enthusiastically. Some became classics.

His translation of Stowe’s novel came out with an altered title: A Chronicle of Black Slaves’ Lamentation. It became an instant sensation, and several major newspapers serialized the story in China. A group of Chinese students in Tokyo were mesmerized by the novel. They had a drama club, Spring Willow Troupe, that decided to adapt it into a play. Yomei’s current neighbor Oyang Yuchien was a key member of Spring Willow Troupe, and he took part in the adaptation, playing a white man in the play. It was staged in 1907 and was so well received that soon afterward, several cities in China also put on versions of the play. Later, in the early 1930s, it was performed widely in Ruijin, the CCP’s Soviet base, to deepen people’s understanding of racial oppression in the United States. Now, decades later, when the United States had become the citadel of world capitalism, the Central Experimental Theater, headed by Mr. Oyang Yuchien, decided to stage the play again so as to reveal these dark pages of American history and also to honor the semicentennial of spoken drama, a new genre, in Chinese theater. But the early script of the play had been lost, so Mr. Oyang decided to write a new play based on Uncle Tom’s Cabin. With Yomei’s help, he produced the lengthy script, making it closer to the spirit of the current time, when people on different continents were all engaged in fighting against racism and the so-called final stage of capitalism—imperialism. Already seventy-one and with his memory failing, Mr. Oyang had to depend on Yomei to produce the play, but he served as a consultant, giving her ideas and suggestions occasionally. His reputation also helped protect the project from too much official interference.

The new script was titled Black Slaves’ Hate. It was a massive play, with nine acts and more than forty characters. Besides the animus highlighted onstage, the slaves were more active and determined in their struggle against the slave owners, fighting for their survival in the land they’d been shipped to. In the novel Stowe advocated for the humane treatment of the slaves snatched from Africa; she held that the educated Africans should eventually be returned to their homeland, where they could start a normal life and build their own democratic countries. Such a notion was already obsolete, and the new play ought to show that the black Americans’ future lay in fighting for their own decent livelihood in America and for equality and justice. So even the protagonist, Tom, was altered. He is no longer a passive Christian who followed the Bible’s teachings to the letter. When refusing to flog his two female slaves as he was ordered to by his master, he exchanges words with his cruel owner, Legree, with dignity and deep passion. Tom tells him: “True, my body was sold to you, but my soul belongs to myself. Although you can make me do the heaviest work, what’s in my mind is different from yours. I’m afraid we’ll never be the same…You can flog people like cattle, but I’ll never raise my hand against an innocent person.” Tom’s condemnation bruises his master’s pride, so Legree begins punching him, then orders his underlings to throw Tom into a deserted barn infested with vermin. He means to starve him into submission. Yet unlike in the novel, in which Legree beats Tom to death, in the new play the unyielding Tom is tied to a tree and set on fire. He is burned to death, which is more striking and more powerful onstage.

Swallowed in flames, Tom makes his last speech: “I used to think everybody could be moved by kindness, but today I have realized that American bosses like you cannot be brought around by kindness. You will have to pay the debt you owe. Even though you don’t pay now, the account will be settled sooner or later. Do you think you can clear the debt by burning me to death? No, the debt you have carved on the hearts of the sufferers will never be wiped out.” So Tom is a totally new character in Yomei’s production and is meant to be a fighter.

In preparing the new script, Yomei abided by the words that John Brown had bequeathed his children: You must hate, hate with an intense passion the source of evil—slavery. She was trying to instill some of John Brown’s spirit into Uncle Tom and the other characters, especially George and his sister Cassy.

At every opportunity, Yomei emphasized the slaves’ enmity, which in turn must also inspire rebellious actions. The undercurrent of the drama is clearly class struggle, which reflects the global élan of the 1960s.

Mr. Oyang Yuchien loved the new script, which bore his name as its author, and which was approved by the theater’s art committee within a week after Yomei had submitted it. Then she began to assemble the various actors and to rehearse the initial scenes.

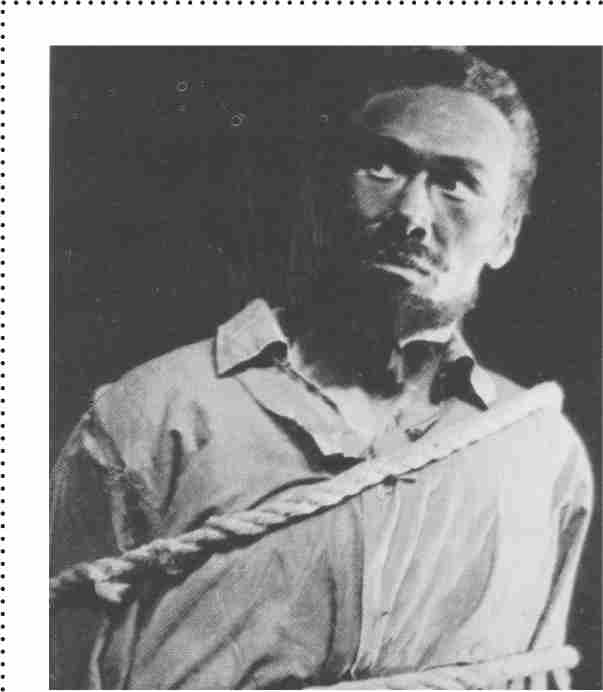

Uncle Tom, played by Tian Cheng-ren

None of the actors had been to America. All the impressions and understanding they had were mainly from writings. Even though Yomei had seen the old movie of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the black-and-white film wasn’t that helpful either, because the new play was much more intense and fiercer in its theme of class struggle and had to have more colors. Still, the movie gave her a picture of what a slave owner’s mansion on a plantation was like, white and grand and wrapped with a veranda. It also showed the interior of the slaves’ quarters. But the stage design mustn’t copy the American movie and had to be brand-new and reflect a distinct Chinese sensibility. It had to manifest a new spirit. Recently Chairman Mao had made a public statement condemning American imperialism and racism, and supporting the civil rights movement in the United States. So Black Slaves’ Hate had to reflect the struggle of the present time as well.

During their rehearsal, Patrice Lumumba, the Congolese popular leader, was arrested and murdered by the authorities of his country. A short documentary film that showed him being apprehended and executed was shown to the Chinese public. With his hands bound from behind, Lumumba was forced onto the back of a truck; he turned around, his eyes blazing with hatred. Yomei told the actors that the flames in Lumumba’s eyes must be a key mental reference in their performance—the oppressed had to fight to survive and must never have any illusions about the oppressors. The acting crew nodded in assent and felt more excited about such a powerful dramatic project.

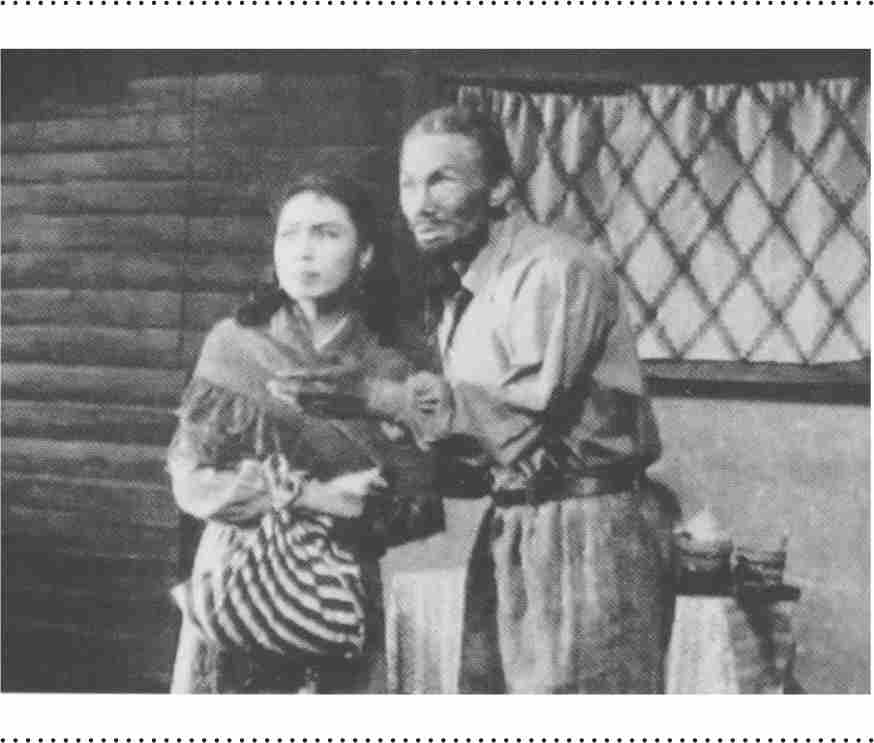

Nevertheless, there were additional small, specific problems that had to be solved case by case. Hsiao Chih, the lithe young woman playing Cassy, couldn’t imagine what the female slave, who was skilled in witchcraft, was like. Yomei couldn’t explain to her in concrete terms and images either. Then one day she chanced upon a statue of a black woman at the home of Liao Chengzhi, the former president of the National Youth Art Theater. The statue had been presented to him by a friend of his in Guyana. With excitement, Yomei took Hsiao Chih to Mr. Liao’s home, where they looked at the statue. The actress was struck by the vivacious beauty of the female figure and kept tutting with praise. Yomei asked her, “Don’t you think Cassy’s stage image should be like this, lovely, evocative, and kinetic, also memorable?” Hsiao Chih nodded in agreement. Thus she became able to proceed with her enactment of Cassy.

In act seven, Tom is viciously flogged by Legree, his new owner. Conventionally the director would ask the actor to show the pain, asking him to moan loudly and even howl. There was little else one could do. But Yomei wouldn’t take the well-trod path. She put twenty-five slaves onstage—when the whip falls on Tom with loud cracks, all the slaves groan and swing their heads from side to side as if being flogged at the same time. As a result, the whole stage trembled with their agony. Every spectator on the rehearsal ground was struck by this drastic manifestation of pain.

Toward the end of the play, Cassy and Emmeline want to flee north together with Tom, but he won’t go and instead urges them to set off without him, because if Legree finds out about their escape, he might dispatch men to track them down. Also, Tom is injured, unable to walk normally. While the two women are leaving, he smiles at them as his way of seeing them off. “That smile must reveal the kindness and depth of his soul,” Yomei told Tian Cheng-ren, the tall scraggy actor playing Tom. “This smile is also meant to assure Cassy and Emmeline not to worry about him.”

Cheng-ren worked so hard on that smile that for a time he seemed unable to smile naturally anymore. Then one afternoon, Lei Ke-sheng, who was playing George, teased him. Young Lei said, “Brother Tian, you’re not Mona Lisa, no need to make your smile too mysterious. Just imagine your wife gave birth to a husky baby boy this morning.” People around laughed. Cheng-ren smiled. Yomei caught that flitting smile on his face and cried out, “That is the smile you should give to Cassy and Emmeline, with a touch of bliss!” So from the next day on Cheng-ren grabbed Lei and wanted him to see if he was reproducing that smile. Eventually he managed to do it with ease onstage. When the play was performed, some people commended that heartbreaking but beatific smile, shaded by a veil of moonlight, saying it displayed so much of Tom’s generous character.

Cassy and Tom in Black Slaves’ Hate

The play turned out to be a huge success. Several rave reviews appeared in newspapers, including a long laudatory article in The People’s Daily by Tian Han, a top playwright serving as the head of the theater bureau in the Ministry of Culture. A visiting African writer saw the play and enthused, “This is so different from the novel and so nuanced. The director is a genius!” One evening a few Congolese among the audience wouldn’t leave after the curtain dropped. They begged the crew to perform the play in Africa and even said that at least it should be recorded on film so that more people could see it. Premier Zhou came to see it too and was greatly impressed. He told Yomei, “I saw several productions of this play, and yours is by far the best.” He also invited the crew to perform it in the Huairen auditorium in Zhongnanhai, where many top leaders saw it, including Liu Shaoqi, Zhu Deh, Chen Yun, and Deng Xiaoping.

Jiang Ching also saw it. She sent along a note of congratulations, saying Yomei must be the number one female spoken drama director in China now. Ching also mentioned two “amazing plays” she’d been working on: Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy and The Legend of the Red Lantern. She was converting them into Beijing operas. Yomei wrote back to thank Ching and said she couldn’t wait to see Ching’s operas. She realized it would be impossible to separate theater from politics and that she might not be able to shun Ching altogether. She’d better learn how to deal with her without making an enemy of her or being exploited.