CHAPTER ELEVEN

“Living in a Tomb”

On Monday, May 22, the night before the Grand Review, Jefferson Davis was incarcerated at Fort Monroe. He did not know whether he would ever see his wife and children again. When he parted with Varina, he told her not to cry. It would, he said, only make the Yankees gloat.

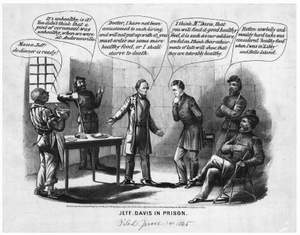

In his captivity, the jailers refused to address him as “President.” They called him “Jeffy,” “the rebel chieftain,” or “the state prisoner.” Soon, through insult, isolation, silence, shackling, constant surveillance, sleep deprivation, and dungeonlike conditions, they would seek to humiliate him and break his spirit. He was, in the words of some newspapers, the archcriminal of the age, a man “buried alive” who must never be set free.

Lincoln had once spoken of this kind of imprisonment:

They have him in his prison house; they have searched his person, and left no prying instrument with him. One after another they have closed the heavy iron doors upon him, and

now they have him, as it were, bolted in with a lock of a hundred keys, which can never be unlocked without the concurrence of every key; the keys in the hands of a hundred different men, and they scattered to a hundred different and distant places; and they stand musing as to what invention, in all the dominions of mind and matter, can be produced to make the impossibility of his escape more complete than it is.

But Lincoln was not, in these 1857 remarks on the Dred Scott decision, speaking of Jefferson Davis. He was, instead, speaking of the “bondage…universal and eternal” of the American slave. Now, the leader of the vanquished slave empire found himself locked in a “prison house” as secure as any built during the previous two and a half centuries of American slavery. Millions of his enemies in the North hoped he would never emerge from his dungeon alive.

The night Davis was placed in his prison cell, Mary Lincoln moved out of the White House. She took with her a suspiciously large number of trunks. Benjamin Brown French was not sorry to see her go. He called on her before she left the presidential mansion: “Mrs. Mary Lincoln left the City on Monday evening at 6 o’clock, with her sons Robert & Tad (Thomas). I went up and bade her good-by, and felt really very sad, although she has given me a world of trouble. I think the sudden and awful death of the President somewhat unhinged her mind, for at times she has exhibited all the symptoms of madness. She is a most singular woman, and it is well for the nation that she is no longer in the White House. It is not proper that I should write down, even here, all I know! May God have her in his keeping, and make her a better woman. That is my sincere wish…”

No government or military official in Washington regretted that Mary would be absent from the next day’s parade.

Early on Tuesday morning, before the Grand Review got under way at 9:00, photographers claimed their positions on the south grounds of the Treasury Building, east of the White House. From there they pointed their cameras up Pennsylvania Avenue to capture the panorama of troops marching toward them, framed by the Great Dome rising in the distance. Other cameramen took photos of the huge crowds gathered in front of Pennsylvania Avenue storefronts. At the Capitol, one photographer aimed his lens at the North Front, where crowds had gathered to watch the troops march up East Capitol Street and swing around the Capitol building on their way down the avenue. When he removed his lens cap, he froze a wondrous, ephemeral moment: blurred figures in motion; a man carrying, on a pole, a sign reading WELCOME BRAVE SOLDIERS, and, strolling through the frame, a young girl wearing a hoopskirt and a straw hat, trailing festive ribbons.

Gideon Welles delayed a trip south to witness the “magnificent and imposing spectacle,” and recorded in his diary:

[T]he great review of the returning armies of the Potomac, the Tennessee, and Georgia took place in Washington…It was computed that about 150,000 passed in review, and it seemed as if there were as many spectators. For several days the railroads and all communications were overcrowded with the incoming people who wished to see and welcome the victorious soldiers of the Union. The public offices were closed for two days. On the spacious stand in front of the executive Mansion the President, Cabinet, generals, and high naval officers, with hundreds of our first citizens and statesmen, and ladies, were assembled. But Abraham Lincoln was not there. All felt this.

General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, who would receive the Medal of Honor for his defense of Little Round Top at Gettysburg, felt it too when he and his men came opposite the reviewing stand: “We miss the deep, sad eyes of Lincoln coming to review us after each sore trial. Something is lacking in our hearts now—even in this supreme hour.”

From his front porch, Benjamin Brown French watched the Ninth Corps of the Army of the Potomac march west, down East Capitol Street on its way downtown, and to President Johnson’s reviewing stand. French, who as commissioner had draped all the public buildings in Washington in mourning for Lincoln, including the Capitol, the Treasury Department, and the White House, now decorated his own house with symbols of joy: “I put a gilded eagle over the front door and festooned a large American flag along the front of the house, the centre being on the eagle, and above the eagle, in a frame placed in the window.”

Then he went to the Capitol, climbed the narrow, twisting staircase to the Great Dome, and beheld the magnificent sight: “We went on the dome, from which we could see troops by the thousands in every direction…more than 50,000 in sight at one time, as we could see the entire length of Maryland Avenue west, Pennsylvania Avenue east, New Jersey Avenue south, and all of Pennsylvania Avenue west from the Capitol to the Treasury, and they were all literally filled with troops. It was a grand and brave sight.”

While Union troops were marching in Washington, others at Fort Monroe entered Davis’s cell and told him they had orders to shackle him. Davis saw the blacksmith with his tools and chains. He told them all that he refused to submit to the humiliation and pointed to the officer in charge and said he would have to kill him first. Davis dared his jailers to shoot him. Soldiers lunged forward to grab him, but Davis, exhibiting some of the strength he had displayed decades earlier when wrestling slaves, knocked one man aside and kicked another away with his boot. Then several men ganged up on him, seized him, and held him down while the smith hammered the shackle pins home. This was supposed to have been done in secret, but like many of the events to unfold in the days to come at Fort Monroe, word was leaked to the press. The Chicago Tribune reported the scuffle, claiming in one headline that Davis was “On the Rampage.” Little did Davis know, his enemies had done him a huge favor.

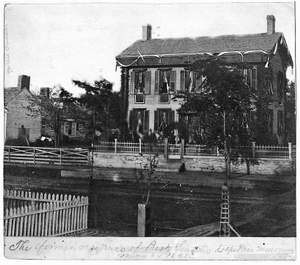

Dy May 24, Lincoln’s home in Springfield, viewed by thousands of funeral visitors during the first week of May, was no longer a center of attention. The delegations of dignitaries who had lined up in front of the house to pose for dozens of souvenir photographs had all left town. But on this day an anonymous photographer, probably local to Springfield, showed up to make the last known image of the Lincoln home draped in mourning. In the photograph, the black bunting, exposed to the elements for weeks, hangs askew, windswept and weather-beaten. No one poses for the camera, and the big frame house looks abandoned, even haunted. Green leaves—new life—sprout from the tree branches that frame the image. All across the nation, people could not bear to take down their wind-tattered, sun faded, and rain-streaked habiliments of death and mourning. Better, many thought, to allow time and the elements to sweep them away.

The May 29 issue of the Richmond Times shocked loyal Confederates who had remained in the city. “Mr. Davis Manacled,” announced the headline. The news was several days old, but Davis’s humiliation was still raw:

[He] has manacles on both ankles, with a chain connecting about three feet long. He stoutly resisted the process of manacling. Rather than submit, he wanted the guards to shoot him. It became necessary to throw him on his back and hold him until the irons were clinched by a son of Vulcan. He exhibited intense scorn, but finally caved in and wept. No knives

WEEKS AFTER THE FUNERAL, THE LAST PHOTOGRAPH OF LINCOLN’S SPRINGFIELD HOME DRAPED IN MOURNING, MAY 24,1865.

and forks are allowed in his cell; nothing more destructive than a soup spoon. Two guards are in his casements continually. The clanking chains give him intense horror.

The Times did not know that by the time it published its report, public outrage, including in the North, had compelled Stanton to telegraph orders to Fort Monroe to have the shackles taken off on May 27 or 28.

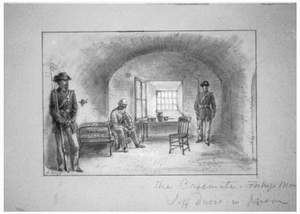

The newspaper report described other details of Davis’s imprisonment: “The windows are heavily barred, and the doors securely bolted and ironed. Two guards constantly occupy the room with him, while in the other room are constantly stationed a commissioned officer and a guard, all charged with the duty of seeing that the accused does not escape. Davis is not permitted to speak a word to any one, neither is any one permitted to speak a word to him. He is literally living in a tomb.”

Feeling in the North was mixed about what should be done with the Confederate president. Some people favored execution. Others suggested mercy, if not for Davis’s sake, then the country’s. On May 29, the Richmond Times reprinted an article from the Springfield, Massachusetts, Republican that warned Northerners of the danger of persecuting Jefferson Davis.

Do we wish to finish the rebellion, to turn out its very ashes? Then make no martyrs. The wounds inflicted in cold blood are what keep animosities alive. At this moment there are a million women in the South who would give all they had to save Jeff. Davis’s life, who would conduct and shelter him…If his life is taken they are ready to dip their handkerchiefs in his blood, to beg locks of his hair, and to perpetuate for a hundred years the sentiment of vengeance. Unless we present them their grievance, in five years he will be remembered only as the author of innumerable woes.

On June 1, the North held a national day of mourning for Abraham Lincoln. Across the nation on the same day, communities remembered their fallen chief and the funeral pageant. Frederick Douglass praised Lincoln as “the black man’s president” in New York City at Cooper Union, and in Providence, Rhode Island, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison honored the Great Emancipator. The timing was not auspicious for Jefferson Davis. Given the bereaved and vengeful mood of the North, Davis was lucky not to find himself on trial before a military tribunal with the eight assassination conspirators locked up at the Old Arsenal. Although Davis did not sit in the prisoner’s dock beside Lewis Powell, David Herold, Mary Surratt, and the others, his reputation did.

But zealous efforts by the government to implicate the Confederate president failed. Indeed, several witnesses who during the trial of the conspirators would give harmful testimony against Davis were exposed as imposters and perjurers. This was the first hint that it might not be so easy to prosecute Jefferson Davis for bloody crimes against the United States. But that did not prevent people from opining on what should be done with him. Through the spring and summer, President Andrew Johnson received many letters advising him to hang Davis or to torture him to death. Few correspondents urged mercy. Hate mail poured in to the Confederate president, taunting him about the terrible doom that must await him.

Two men, one his jailer, the other his doctor, figured prominently in Davis’s imprisonment at Fort Monroe. The War Department appointed a Civil War hero, Major General Nelson A. Miles, to take charge of the state prisoner. Miles, only twenty-six, had fought in the battles of Seven Pines, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville, had been wounded in each engagement, and would receive the Medal of Honor for his valor at Chancellorsville. He was not awed by or sympathetic to the rebel president, and he became Davis’s principal antagonist. It was Miles, acting under the discretionary authority granted him by Stanton, who ordered that Davis be shackled. He would regret that decision.

The chief medical officer of the fort, forty-three-year-old Lieutenant Colonel John J. Craven, was a self-made physician, inventor, and businessman, and he immediately empathized with Davis’s plight. He requested an extra mattress and pillow for Davis’s iron bed frame, provided tobacco, and objected to the shackles. Craven saw his patient every day, and Davis charmed—even mesmerized—him. Soon they fell into the easy habit of conducting long conversations on a variety of subjects. They became friends, and Craven tried to improve the harsh conditions of Davis’s imprisonment in every possible way.

The assassination conspiracy trial continued through June, and its coverage dominated the headlines all month long. Every day, newspapers published transcripts of the previous day’s testimony, and the public devoured each new, sensational revelation. The trial of the century stole attention from other events in Washington, including the first anniversary of the funeral for the victims of the Arsenal explosion and fire. On June 17, 1865, a monument to the women was erected over their common grave. The white stone sculpture by artist Lot Flannery depicted a mourning girl with clasped hands and downturned head standing atop a tall pillar inscribed on three sides with the names of the dead. On the front side was a panel carved in deep bas-relief that froze in time the laboratory building at the moment of the explosion, with rays of blinding light, fire, and smoke. Winged hourglasses ringed the monument to remind all viewers that life is fleeting. But no one was present on June 17 to heed that warning. The monument was erected without a dedication ceremony. The dignitaries and crowds who had thronged there one year earlier were absent that day. No reporters wrote stories. Perhaps the national capital was spent, its emotions drained. Perhaps there were no more tears left to shed.

On July 6, the most thrilling news since the capture and death of John Wilkes Booth raced through Washington. All eight defendants in the conspiracy trial had been convicted, three had been sentenced to life in prison, and four would be put to death by hanging the next day. Many Americans, although disappointed that Davis was not the fifth criminal standing on the scaffold at the Old Arsenal on the blazing hot afternoon of July 7, relished the verdicts. By the end of the

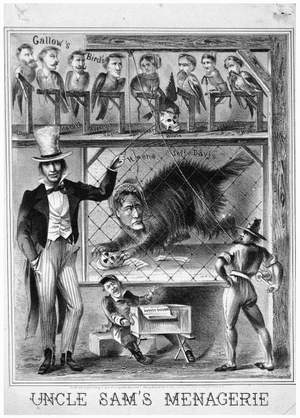

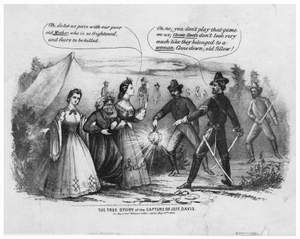

THIS FANCIFUL PRINT DEPICTS DAVIS AS A CAGED HYENA WEARING A LADIES’ BONNET. THE LINCOLN ASSASSINATION CONSPIRATORS PERCH ABOVE HIM ON GALLOWS, FORESHADOWING THEIR EXECUTION.

trial, sober government officials had to concede that no credible evidence linked Davis to Lincoln’s assassination. The Confederate president felt no empathy for his fallen foe, but would have considered it dishonorable to order his murder, and beneath his dignity to exult in it. If he was to be tried, it would be not for Lincoln’s murder but for treason and war crimes.

Nonetheless, the hanging of the conspirators was an ill omen for Jefferson Davis. It showed that the War Department was ready to impose postwar death sentences, even upon Mary Surratt, the first woman executed by the federal government. Soon a Confederate officer, Captain Henry Wirz, would go on trial for crimes committed against Union prisoners of war confined at Andersonville where, allegedly, soldiers had been murdered, starved, and torn apart by vicious dogs. By now Davis had been given access to newspapers, and he must have read accounts of the gruesome hangings—the snap of the rope had not broken the necks of all the condemned and some of them strangled to death slowly—and speculated whether a similar fate awaited him.

On July 13, six days after the execution of the assassination conspirators, New Yorkers meted out symbolic punishment to the rebel chief when they hanged him in effigy. It began with P. T. Barnum. Back in May, when Stanton had refused to sell him the spurious “capture” dress, the brilliant entertainer was inspired to concoct a more exciting exhibit. He created a life-size wax figure of Jefferson Davis, dressed in a bonnet, hoopskirt, and boots, and displayed the mannequin in a tableau surrounded by other life-size figures dressed as Union cavalrymen in the act of apprehending the Confederate president.

This was not the only wax Jefferson Davis that entertained Americans in the summer of 1865. Professor Vignodi, an ambitious talent of the paraffin arts, created a life-size tableau of Lincoln and Booth in the box at Ford’s Theatre, a presidential funeral hearse, and, for the benefit of those who missed the opportunity to view the corpse, a replica of Lincoln’s coffin with a life-size figure of the dead president resting inside it. He followed up these morbid, self-proclaimed masterpieces with a life-size wax figure of Davis. A third wax figure of the rebel president showed up at a Sanitary Fair in Chicago.

On July 13, a fire broke out at Barnum’s huge, four-story American Museum. While flames engulfed the entire building, thousands of New Yorkers rushed to the scene and watched as the live animal exhibits, injured by hideous burns, fled the museum and died agonizing deaths in the street. The New York Times described desperate efforts to save the exhibits. “On reaching the main salon, where the wax figures stood, [a performer] found great confusion existing. A man was endeavoring to save a Swiss animated landscape, while others tried to get out various other articles, including the wax figures…the crowd rushed to the front windows, and speedily emptied their arms of the gimcrack articles, throwing them indiscriminately into the street.” Somebody in the museum tried to rescue President Davis, which amused both the Times and the crowd in the streets.

One man had the JEFF. DAVIS effigy in his arms and fought vigorously to preserve the worthless thing, as though it were a gem of rare value. On reaching the balcony the man, perceiving that either the inanimate Jeff. or himself must go by the board, hurled the scarecrow to the iconoclasts in the street. As Jeff. made his perilous descent, his petticoats again played him false, and as the wind blew them about, the imposture of the figure was exposed. The flight of dummy Jeff. was the cause of great merriment among the multitude, who saluted the queer-looking thing with cheers and uncontrollable laughter. The figure was instantly seized, and bundled off to a lamp-post in Fulton Street, near St. Paul’s Church-yard, and there formally hanged, the actors in the mock tragedy shouting the threadbare refrain, commencing the “sour apple” tree.

The image of a cowardly Confederate president masquerading as a woman titillated Northerners but outraged Southerners. In Georgia, Eliza Andrews received letters and Northern newspapers from friends in Richmond and Baltimore that outlined the accusation. On August 18 she recorded in her diary her first encounter with the Davis caricatures:

I hate the Yankees more and more, every time I look at one of their horrid newspapers and read the lies they tell about us…The pictures in “Harper’s Weekly” and “Frank Leslie’s” tell more lies than Satan himself was ever the father of. I get in such a rage when I look at them that I sometimes take off my slipper and beat the senseless paper with it. No words can express the wrath of a Southerner on beholding pictures of President Davis in woman’s dress; and Lee, that star of light…crouching on his knees before a beetle-browed image of “Columbia,” suing for pardon! And these in the same sheet with disgusting representations of the execution of the so-called “conspirators” in Lincoln’s assassination. Nothing is sacred from their disgusting love of the sensational.

If the first wave of Davis caricatures in newspapers and prints angered Eliza, then the sheet music artwork and satiric lyrics would have infuriated her even more. Davis was pilloried in popular song, many further perpetuating the widespread belief that he had been captured dressed in women’s clothing, wearing a bonnet while carrying a large knife and a bag of gold. Lyrics referenced with delight the circumstances of his capture on the run:

One bright and shining morning, All in the month of May,

The C.S.A. did “bust” up, and Jeff he ran away;

He grabb’d up all the specie, And with a chosen band,

This valiant man skedaddled, To seek some other land…

But good old Uncle Sam, Sent his boys from Michigan,

And in the state of Georgia, They found this mighty man;

He’d girded on his armor, his SKIRT it was of STEEL,

But when he saw the soldiers, Quite sick did poor Jeff feel…

So when this gallant SHE-ro, Did see the blue coats come,

He found he had business, A little way from home;

In frock and petticoat He thought he could retreat,

But could not fool the Yankees They knew him by his feet.

Another song repeated the accusation that Davis had fled dishonorably, with stolen gold:

Jeff took with him the people say, a mine of golden coin.

Which he from banks and other places, managed to purloin:

But while he ran, like every thief, he had to drop the spoons,

And may-be that’s the reason why he dropped his pantaloons!

For one song, “The Last Ditch Polka,” printed sheet music shows a rat with Jefferson Davis’s face pictured inside a cage within a prison cell surrounded by chains, guarded by an eagle. Some lyrics, more dark in tone, imagined with delight the punishments awaiting Davis:

And when we get him up there boys, I’m sure we’ll hang him high,

He will dance around on nothing, in the last ditch he will die.

Another, “Hang Him on the Sour Apple Tree,” described as a “sarcastical ballad,” has a cover engraving that pictures a noose on a tree and describes the traitor Jefferson Davis getting what he deserves, speaking in Davis’s voice: “Now all my friends both great and small, / A warning take from me. / Remember when for ‘plunder’ you start, / There’s a Sour Apple Tree!” In bars and public places all across the North, people gathered and sang the chorus from the most popular song that spring: “We’ll hang Jeff Davis from a sour apple tree.”

Varina Davis is a prominent character in the story of her husband’s capture, rumored to have spoken harshly, defiantly, to the soldiers who captured the president: “His wife now like a woman true, / Said don’t provoke the President / Or else he may hurt some of you. / He’s got a dagger in his hand.”

After several weeks of silence, Varina received her first letter from Jefferson since his capture. It was the beginning of a moving jail-house correspondence under difficult conditions.

21 Aug. ‘65

My Dear Wife,

I am now permitted to write you, under two conditions viz: that I confine myself to family matters, and that my letter shall be examined by the U.S. Attorney General before it is sent to you.

This will sufficiently explain to you the omission of subjects on which you would desire me to write. I presume it is however permissible for me to relieve your disappointment in regard to my silence on the subject of future action towards me, by stating that of the purpose of the authorities I know nothing.

To morrow it will be three months since we were suddenly and unexpectedly separated…

Kiss the Baby for me, may her sunny face never be clouded, though dark the morning of her life has been.

My dear Wife, equally the centre of my love and confidence, remember how good the Lord has always been to me, how often he has wonderfully preserved me, and put thy trust in Him.

Farewell…Once more farewell, Ever affectionately your Husband

Jefferson Davis

In October, the conditions of Davis’s confinement improved. He was removed from his damp cell in the casemate wall and relocated to private rooms in Carroll Hall in the fort’s interior. Better treatment was a sign that he might be staying awhile, and that he would not be leaving soon for trial.

The familiarity between Davis and Craven did not go unnoticed by Miles, and in the fall of 1865, it was rumored that Craven would be replaced. Davis wrote him a letter: “With regret and apprehension I have heard that you are probably soon to leave this post. To your professional skill and brave humanity I owe it…that I have not been murdered by the wanton tortures and privations to which my jailor subjected me. Loaded with fetters when but little able to walk without them, restricted to the coarsest food, furnished in the most loathsome manner…and confined in a damp casemate the atmosphere of which was tainted by poisonous exhalations, you came to my relief…you have alleviated my sufferings and supplied my wants…you have been my protection.”

In November, Henry Wirz, the commander of the Andersonville prisoner of war camp, was found guilty of war crimes and hanged at the Old Capitol Prison, across the street from the U.S. Capitol. Photos taken of the execution show Wirz standing on the scaffold, the rope around his neck, with the Great Dome as the backdrop. Davis may have seen woodcuts of the hanging in Harper’s Weekly. This was the first postwar execution by the federal government for crimes unrelated to the Lincoln assassination. It set an ominous precedent for Davis.

The next month, Davis was allowed his first visit from Rev. Minnegerode. Both men had traveled far since that beautiful April Sunday morning in church nine months ago. The War Department warned the minister to limit his conversation to spiritual matters. The department was possessed by a paranoia that rebel daredevils might break Davis out of prison, and that any visitor might be transmitting secret messages of the plot.

In December, after Craven had one of Davis’s tailors send a fine and warm winter coat, Miles and his superiors became incensed. Who was this rebel chief to enjoy such luxuries, and who was this doctor so eager to supply them? Craven was removed as Davis’s physician on Christmas Day, and a month later he was mustered out of service and returned to private life. But he had the last laugh. Unbeknownst to Miles, Craven had kept a diary about the conditions of his patient’s imprisonment.

Christmas was a hard time for Davis. A year ago, his family had sat around their dining room table in Richmond, feasting on turkey and a barrel of apples that an admirer had sent them as a gift. Now all Varina could offer was a sad letter: “Last Christmas we had a home—a country—and our children—and yet we would not be comforted for our ‘little man’ [Joseph Evan Davis, who had fallen to his death several months before] was not—This Christmas we have a new child, who has seen but one before.” Overcome, she thought of dead sons and cemeteries: “That little grave in Richmond, the other in Georgetown [for Samuel Emory Davis, 1852–1854] is ever fresh to me.” Perhaps realizing that her letter had turned too morbid, Varina told Jefferson that her love for him was stronger than sad memories: “But fresher—more enduring still is the love which at this season nearly twenty two years ago filled my heart, and has kept it warm and beating ever since.”

As the new year came, the U.S. government still had not decided what it wanted to do with Jefferson Davis. Would 1866 bring him life? Or death?

On January 29, 1866, a young girl in Richmond, Emily Jessie Morton, wrote to Davis to cheer him up:

I hope that you will not think me a rude little girl to takeing the liberty of writing to you, but I want to tell you how much I love you, and how sorry I feel for you to be kept so long in Prison away from your dear little children…I go to school to Mrs. Mumford where there are upwards of thirty scholars all of which love you very much and are taught to do so. When we go to Hollywood [cemetery] to decorate our dear soldiers graves on the 31st of May your little Joes grave will not be forgotten.

She told him she loved him so much that her teasing schoolmates called her little “Jefferson Davis.”

From the time of Davis’s capture in the spring of 1865 to the winter of 1866, Varina Davis waged a relentless one-woman campaign to obtain better treatment for her husband, to visit him in prison, and, ultimately, to gain his freedom. She had been a popular and well-liked figure in antebellum Washington, including among important Northern politicians, and now she used every social and political skill she had learned since her Mississippi girlhood to save her husband. She wrote letters, secured personal meetings, and influenced newspaper coverage.

Six months later, on April 25, 1866, Varina Davis sent a letter to President Andrew Johnson: “I hear my husband is failing rapidly. Can I come to him? Can you refuse me? Answer.” Her note alarmed Johnson, who asked Stanton to advise him immediately. The secretary of war, who had kept Jefferson and Varina apart for one year, relented. Miles warned his superiors what a dangerous foe she could be, and a few weeks after she arrived at Fort Monroe, several newspaper articles accused him of punishing his prisoner with inhuman treatment. Enraged, on May 26 Miles forwarded the articles to General E. D. Townsend at the War Department: “It is true I have not made [Jefferson Davis] my associate and confidant or toadied to his fancy…[but] the gross misrepresentations made by the press infringes upon my honor and humanity and I am unwilling to let such statements to go unnoticed.” The newspaper stories were nothing compared with what was coming. Dr. Craven had written a book.

Varina received permission to visit Jefferson. She arrived at Fort Monroe on May 3, 1866, and brought her little girl with her. She had left the rest of her children in the care of others, deciding her first duty was to save her husband’s life. But before she was permitted to see him, the War Department had demanded that she promise in writing that she would not help him escape, or smuggle “deadly” weapons—including pistols, knives, or explosives—into his cell: “I, Varina Davis, wife of Jefferson Davis,” she agreed, “for the privilege of being permitted to see my husband, do hereby give my parole of honor that I will engage in or assent to no measures which shall lead to any attempt to escape from confinement on the part of my husband or to his being rescued or released from imprisonment without the sanction and order of the President of the United States, nor will I be the means of conveying to my husband any deadly weapons of any kind.”

The former first lady of the Confederacy might have bristled at the language—she considered it her right, not a “privilege,” to see her husband, and she viewed their one-year separation an outrage, but now was not the time to argue. President Johnson had yielded to her will. She signed the document and gave her parole. Now nothing would stop her from reuniting with her beloved “Banny.”

This visit was followed a few weeks later when Davis signed a parole that gave him liberty to wander the fort with Varina during the day.

FORT MONROE, May 25, 1866

For the privilege of being allowed the liberty of the grounds inside the walls of Fort Monroe between the hours of sunrise and sunset I, Jefferson Davis, do hereby give my parole of honor that I will make no attempt to nor take any advantage of any opportunity that may be offered to effect my escape therefrom.

JEFFERSON DAVIS

Varina had won the first round. She had been reunited with her husband. Soon she won another victory—the right to move into the prison and share Jefferson’s quarters. If she could not take him home to live, then she and their daughter would live with him at Fort Monroe. Now she prepared for the next stage of her battle with federal authorities—her effort to win his freedom.

In June 1866, a New York publisher released Craven’s book under the long-winded title Prison Life of Jefferson Davis, Embracing Details and Incidents in His Captivity, Particulars Concerning His Health and Habits, Together with Many Conversations on Topics of Great Public Interest. It caused a sensation and created nationwide sympathy for the imprisoned fallen president, just as Craven hoped. Even most of Davis’s enemies did not want to see him languish and die in captivity. As a literary effort, Prison Life was riddled with exaggerations and errors. Indeed, when Davis obtained a copy he penciled corrections in the margins of almost two hundred pages. Some critics said that the book was a fraud. It did not matter. As a piece of political propaganda, the book was a work of genius. The month after its publication Joseph E. Davis wrote to his brother: “The prison life by Dr. Craven is I think exerting an influence even greater than expected.” In Europe, public opinion favored Davis. The Pope sent him an inscribed photograph and a crown of thorns.

Three months later, Miles would be relieved of his command. The fifteen-month assignment had not been to his liking, but he resented leaving his post under a cloud. His career survived the embarrassment, and he enjoyed future success in the west fighting Indians, and rose in rank until he commanded the entire U.S. Army.

In the summer of 1866, two ghosts from the Lincoln assassination visited Fort Monroe. On June 5, Surgeon General Joseph A. Barnes called upon Davis. Barnes had watched Lincoln die. On August 12, Assistant Surgeon General Charles H. Crane visited Davis. He and Barnes had witnessed the autopsy and watched Curtis and Woodward cut open Lincoln’s head and remove his brain. They had come to evaluate Davis’s health and to ensure that he did not die while in Union captivity. Stanton wanted no martyrs. Did Davis know what they had seen? No records survive to indicate whether the doctors discussed the assassination with him.

By the fall of 1866, the government had still taken no action to prosecute Davis for treason. He welcomed his trial, whatever its result. If he was acquitted, then the South was not wrong—it did have the constitutional right to leave the Union, and secession was not treason. If he was found guilty, he was happy to suffer on behalf of his people. His death, he believed, would win mercy for the South. The U.S. government wanted neither result. A federal court verdict declaring secession not treasonable would overturn the whole purpose and result of the war. Some of the ablest attorneys in America had offered to defend Davis, and a guilty verdict was by no means certain. And a guilty verdict, followed by Davis’s execution, would create a martyr and might inspire the South to rise up again. John Reagan said it would be best for all concerned to release Davis: “I urged that the welfare of the whole country would be subserved by setting him free without a trial; for the South it would be a signal that harsh and vindictive measures were to be relaxed; and for the North it would indicate that they were willing to let the decision of the right of secession rest where it was and not try to secure a judicial verdict…the war had passed judgment and that hereafter secession would mean rebellion.”

While the government dithered, Davis lingered in legal limbo through the winter of 1867. But by the spring, the federal government finally decided that it wanted Davis off its hands. He would be released on bail, preserving the right to try him at some future time. By prearrangement, his attorneys would initiate proceedings to free him and the government would not oppose them. On May 8, 1867, former president Franklin Pierce visited Davis in prison and congratulated him on his pending release.

On May 10, the second anniversary of Davis’s capture, a writ of habeas corpus was served on the commander of Fort Monroe. At 7:00 A.M. on May 11, Burton Harrison, Joseph E. Davis, Jefferson’s brother, and several others escorted the former Confederate president, not quite a free man yet, to the landing at Fort Monroe, where he boarded the steamer John Sylvester for Richmond. At 6:00 P.M. Davis reached Rocketts, the same place where, two years earlier, Abraham Lincoln had landed in Richmond to a tumultuous welcome from the city’s slaves. Now the white citizens welcomed Davis back to his old capital. As he passed, men uncovered their heads and women waved handkerchiefs. “I feel like an unhappy ghost visiting this much beloved city,” Jefferson told Varina. A carriage drove them to the Spotswood Hotel, where they were taken to the same rooms they occupied in 1861.

On Monday morning Davis and his counsel appeared in federal court, in the same building once occupied by his presidential office. The $100,000 bond was signed by an unexpected list of names: Davis, Horace Greeley, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Gerrit Smith, the famous abolitionist, and one of the “Secret Six” who had backed John Brown. Smith proclaimed that the war had been the fault of North and South: “The North did quite as much as the South to uphold slavery…Slavery was an evil inheritance of the South, but the wicked choice, the adopted policy, of the North.” After Davis was freed on bail, he left the courtroom and was surrounded by a crowd of supporters; according to his principal legal counsel, Charles O’Connor, “poor Davis…wasted and careworn, was almost killed with caresses.” Davis returned to the Spotswood, where he and Varina received friends.

On May 13 Davis posted bail, the court released him, and he walked out a free man. In 1867, the Lincoln assassination conspirators were either dead or in prison, Captain Wirz had been executed for war crimes and Jefferson Davis was allowed to leave custody as a free man, never having been tried, let alone found guilty of any crime. The man who led the campaign to divide the nation, the man who gave orders to fight and kill Union soldiers, was never tried. The importance of this cannot be overstated. To Davis’s partisans, this meant that no federal court had ever ruled that secession was unconstitutional or treasonous. Thus, they believed, Davis had done no wrong. To Northerners, whatever happened or did not happen to Davis in a court of law, he remained a traitor. If he was freed, it was for prudential reasons, to heal the wounds of war, not to achieve legal justice. His first act, one that would set the tone for the remainder of his life, was one of remembrance. He took flowers to the grave of his son Joseph Evan Davis at Hollywood Cemetery, and while there he also decorated graves of Confederate soldiers. A friend wrote to Varina Davis to assure her that in the joy over the president’s release, the people of Richmond had not forgotten their dead son: “Last Friday [June 1], Hollywood was glorified with flowers. The little one who sleeps here was not forgotten. Garland upon garland covered every inch of turf and festooned the marble that bore the beloved name, some with the touching words, ‘for his Father’s sake.’”

On June 1 a Confederate officer who had served under President Davis sent him a heartfelt letter that described the “misery which your friends have suffered from your long imprisonment,” adding that “to none has this been more painful than to me.” The letter rejoiced in Davis’s freedom: “Your release has lifted a load from my heart which I have not words to tell, and my daily prayer to the great Ruler of the World, is that he may shield you from all future harm, guard you from all evil, and give you the peace which the world can not take away. That the rest of your days may be triumphantly happy, is the sincere and earnest wish of your most obedient faithful friend and servant.” The letter was signed by Robert E. Lee.

After his release, Davis was forced to ask himself questions for which he had no immediate answers. What did the future hold? Where would he go? What would he do? How would he live? How would he earn money? Like much of the South, his life was in ruins. He had lost everything. He had no cache of secret gold. His plantation was in ruins, no crops grew there, and he owned no slaves to work the fields. They had all been emancipated. Union soldiers had looted his Mississippi home of all valuables. They even stole his old love letters from Sarah Knox Taylor.

He also had to decide what he must not do. His behavior would be scrutinized by Northerners and Southerners alike. He vowed to do nothing to bring dishonor upon himself, his people, or the Confederacy. Because so many Southerners were poor, he decided that he would not shame himself by accepting charity from his supporters while others were in need. He would not speak publicly against the Union or Reconstruction, he decided, out of fear that his words might cause his people to be punished. Nor would he run for public office. He knew without doubt that he could be elected to any political position in the South. But to seek office, he would have to take a loyalty oath to the Union, something he would never do. To swear that oath, to recant his views, to say the South was wrong, would betray every soldier who laid down his life for the cause. He would rather suffer death. And, last, he decided he would never return to Washington, D.C., the national capital he once loved and the scene of many of his greatest achievements and happiest days.