CHAPTER TWELVE

“The Shadow of the Confederacy”

For the first time in his life, Davis needed a job. It was a shocking predicament for a member of the elite, planter class. But he had no choice. He needed money and stability, and the quest for it preoccupied him. For the next two years, he wandered and pursued opportunities that led nowhere. In November 1869, he was offered the presidency of the Carolina Life Insurance Company at the impressive annual salary of $12,000—nearly half the pay of the president of the United States. He took the job. But Davis’s days as a “business man” were numbered. An epidemic killed too many customers, and the economic downturn put the company out of business. Davis pursued other moneymaking opportunities, and he considered various schemes that others proposed to him, but he never achieved the financial success that he craved. Failure embarrassed him.

In 1870, the whole South mourned the death of its great general, Robert E. Lee. Davis spoke at the memorial service with sadness and great eloquence, and it was there that he found the true purpose of his remaining days—remembering and honoring the dead. Soon,

the theme of “The Confederate Dead”—the idea of a vast army of the departed who haunted the Southern landscape and memory—swept the popular imagination. Soon, veterans’ groups, historical societies, and women’s associations labored to recover the dead from anonymous wartime graves, to build cemeteries for them and to mark the land where they shed their blood with monuments of stone, marble, and bronze. Later, Davis became the symbol of this movement. He was the link between the Confederate living and the dead. For now, Lee’s unexpected death was a warning to Davis that he should not wait too long to tell his story. As early as March 30, 1870, Davis told Burton Harrison that he wanted to write a book: “It has been with me a cherished hope that it would be in my power before I go down to the grave to make some contribution to the history of our struggle.” Lee had hoped to do the same. The general had begun to gather documents. He examined his official papers. But before he could write his memoirs, he died.

In the 1870s, Davis hit his stride as a keeper of Confederate memory. He wrote articles. He read histories of the war written by generals and political leaders. He kept up an active correspondence and answered countless inquiries about the conduct of the war. He supported the creation of the Southern Historical Society. The North may have won the war on the battlefield, but the South would not lose it a second time in the books. Davis became the titular head of a shadow government, no longer leading a country, but leading a patriotic cause devoted to preserving the past.

Davis became a fixed symbol in a changing age. He witnessed the passing of an era and the rise of a different, modern America. The U.S. Army fought new wars on the western frontier, and in 1876, when America was set to celebrate its national centennial, the flamboyant Civil War general George Armstrong Custer found death at the Little Bighorn, eleven years after Appomattox. To take advantage of the patriotic fervor during the centennial, grave robbers plotted to kidnap Lincoln’s corpse and ransom it for a huge cash payment. They broke into the tomb but were arrested. Davis witnessed the industrialization of the nation, the invention of electric lights, and the first hints of America’s future role as a global power. He also witnessed the plight of blacks during Reconstruction in the postwar South, and what happened to them after 1877, when the last of the federal occupying troops returned to the North. In a few years he would read of the assassination of another president, James Garfield, who survived the Civil War only to be shot in the back at a Washington, D.C., train station.

Throughout this era, Davis experienced financial insecurity and

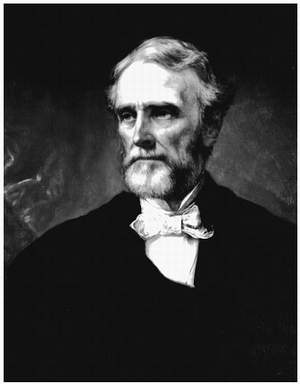

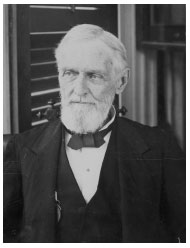

domestic instability. He lacked a proper income or a real home. In 1877, he found his sanctuary at last. A longtime friend and widow, Sarah Dorsey, invited Davis to visit her Mississippi Gulf Coast estate, Beauvoir, near Biloxi. The visit became permanent, and Dorsey willed the property to Davis upon her death. Beauvoir became his haven. It relieved him of significant financial distress, gave him a place to live, and allowed him to finish his book. As Davis labored to complete his memoirs, he also found here, fourteen years after the end of the war, and twelve years since his freedom, a kind of peace. As the years passed at Beauvoir, he became more handsome. His face softened. Photographs from the Gulf coast years capture a gentle smile absent from photos taken earlier in his life, in the 1850s and 1860s.

In 1881, Jefferson Davis published his magnum opus, his two-volume memoir Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. This was not a conventional memoir that tells the story of the subject’s life. Instead, Rise and Fall was in large part a massive, legalistic, dense, and impersonal defense of state’s rights, secession, and Southern independence. It was a dry work of history and politics, not an emotional telling of a riveting life. Yes, partisan publications, including the Southern Historical Society Papers, reviewed it favorably. Loyal Confederates purchased more than twenty thousand copies, but the work did not become a national sensation. It was no more than a moderate, regional success. The heavy volumes may have revealed the contents of Davis’s analytical mind, but they did not unlock the secrets of his heart.

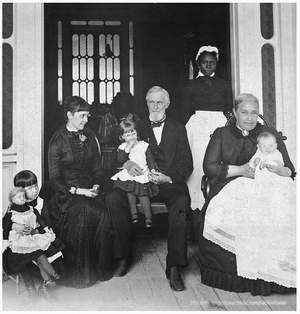

His memoir done, Davis seemed destined for a quiet life at Beau-voir: receiving guests, dining with friends, writing letters, and sitting on the veranda sporting a jaunty straw hat and enjoying the sea breezes. Visiting journalists seemed surprised when they found not an embittered old man, but a genial host and superb conversationalist.

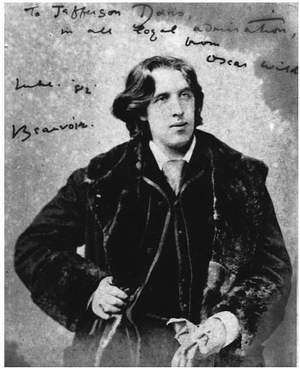

In June 1882, Davis received the most unusual guest to ever visit Beauvoir—the Irish author Oscar Wilde. During his lecture tour to Memphis, an interviewer found him in his hotel room with a set of Davis’s Rise and Fall on the table. Wilde said, “Jefferson Davis is the man I would most like to see in the United States.” Wilde dispatched a letter to Davis asking if, after Wilde lectured in New Orleans, he might visit Beauvoir. The press learned of the fascination, and on June 23, the Mobile Register wrote this about the forthcoming meeting: “We understand that ex-President Davis has invited Mr. Wilde to pay him a visit at Beauvoir…and that the aesthete has accepted.” Almost half a century—and other experiences—separated the seventy-four-year-old senior statesman from the twenty-six-year-old literary voluptuary. The Register could not resist commenting on the bizarre appointment:

“It is scarcely conceivable that two persons can be more different than the ex-President of the Confederacy and the ‘Apostle of aestheticism,’ as known to report; and we confess to sufficient curiosity to desire to know the bent of their coming, protracted interview.”

Interviewed in New Orleans in advance of the meeting by the Picayune, Wilde spoke well of the Confederacy and Davis: “His fall after such an able and gallant pleading in his own cause, must necessarily arouse sympathy.”

At dinner, Varina Davis, her daughter Winnie, her cousin Mary Davis, and Oscar Wilde did most of the talking. Jefferson did not say much as he scrutinized the man who must have appeared to him an odd, even alien, creature. The former president retired early, and afterward, Wilde delighted the literature-loving women until late in the night. The next day, after Wilde departed, Davis rendered his laconic verdict to Varina: “I did not like the man.”

Wilde came to the opposite conclusion about his taciturn host. He left a special gift on Davis’s desk—an oversized, presentation photograph inscribed: “To Jefferson Davis in all loyal admiration from Oscar Wilde, June’“82—Beauvoir.” In Davis’s world, it was a cheeky gesture. He did not solicit the memento, and its presentation suggested that Wilde considered himself a peer of the Confederacy’s first man. It was Davis’s introduction to America’s burgeoning popular culture of celebrity.

In the 1880s, Davis did not seek out feuds, but when insulted or provoked, he was not one to seethe in silence. He planned to speak at the dedication of the Robert E. Lee mausoleum in Lexington, Virginia, on June 28, 1883. But when he learned that his archenemy, General Joseph E. Johnston, would preside over the event, Davis backed out. He refused to share the stage with the man who had surrendered his army to Sherman in North Carolina, dooming, in Davis’s opinion, the Confederacy’s last hope east of the Mississippi in April 1865. And it was Johnston who, in an outrageous defamation, had accused Davis of stealing a fortune in Confederate gold. In his youth, Davis would have challenged Johnston to a duel. Instead, his surrogates advised him to remain above the fray while they unleashed a ferocious verbal assault.

In November 1884, Davis counterattacked against charges by General Sherman that Davis had been at the center of a conspiracy to “enslave” the North and not merely win Southern independence. As proof, the general claimed that he had seen secret letters and overheard private conversations implicating Davis. Davis savaged his antagonist. “I have been compelled to prove General Sherman to be a falsifier and a slanderer in order to protect my character against his willful and unscrupulous mendacity…He stands pilloried before the public and all future history as an imbecile scold, or an infamous slanderer—As either he is harmless.”

By early 1886, Jefferson and Varina were living a quieter life at Beauvoir. Jefferson received inquiries from strangers, or from people he once knew. Many asked if he remembered them. He maintained his passionate interest in Confederate history and how the war was remembered. He hoped to live to celebrate his eightieth birthday in two years. But given his lifelong health problems, he must have felt he that he was lucky to have lived that long. Many times over the years, death had tried to pull him into the grave, but his stubborn body had fought back and willed itself to live. He had lived long enough to write Rise and Fall, to correct errors in the record, to survive many of his foes, and to make his own peace with the past. The once-stern expression on his face had softened, and, strangely, the older he got the happier he looked. Yes, he had suffered. He could tally his losses: his first love, Knox Taylor; his first country, the old Union of the United States; his cause of Southern independence; his war; and his presidency; for a time, his liberty; and his sons, now dead, all of them. But in 1886, Davis was serene and at peace at his Gulf Coast sanctuary. His days as a public man seemed at an end. He planned to make no more public appearances, deliver no more speeches before tumultuous crowds, and undertake no more tours of his vanished empire.

Then the invitation came. Would he, the letter from the mayor of Montgomery asked, come to lay a cornerstone for the monument to Alabama’s Civil War dead? And perhaps their former president would agree to say a few words in memory of them? Davis could not say no.

When, accompanied by his daughter, Winnie, he boarded the train at the depot half a mile from Beauvoir, he could not have known that he would return from this trip a different man. He did not know his journey would bring to the surface emotions long buried in Southern hearts, and his own. He did not know that by its end, almost a quarter century after the end of the war, the South would love him more than it ever did. Reporters went on the trip, including Frank A. Burr of the New York World. Burr had pursued other ghosts from the war. He had written about the Lincoln assassination, and, years after the war, he traveled to Garrett’s farm in search of the legend of John Wilkes Booth. Lincoln and Booth were long dead. Now, on this journey, Burr would travel with a living ghost from the past.

On a stop on the way to Montgomery, Davis had two encounters with well-wishers. “At one station,” reported the Atlanta Constitution, “a soldier with a wooden leg got on board and bidding goodbye to Mr. Davis slapped his wooden leg and said: ‘That’s what I got from the war but I’m proud of it.’ To this Mr. Davis responded with a hearty ‘God bless you.’ At another station an old colored woman, a former slave of Mr. Davis, was loud in her blessings of her old master.” These were the first hints of what lay ahead.

Davis arrived in Montgomery, the first capital of the Confederacy, on April 28. Just before the train rolled into the station, General John B. Gordon, one of Davis’s favorite Confederate officers and who now sought a political career, spoke to the crowd: “Let us, my countrymen, in the few remaining years which are left to our great captain, seek to smooth and soften with the flowers of affection the thorny path he has been made to tread for our sake.” Then train pulled in, cannon fire erupted, and thousands cheered. A drenching rain thwarted a major public reception at the railroad depot. When Davis disembarked from his car, he got into a carriage that drove him to the Exchange Hotel, where he had spent the night before his inauguration as provisional president. Bonfires and electric lights illuminated the route.

Davis prepared to exit the carriage and walk into the hotel. He stood erect, but stayed in the carriage. He paused and looked over the immense crowd. Then he spoke: “My countrymen, my countrymen, with feelings of the greatest gratitude I tender you my most sincere thanks for your kind reception.”

The next day the New York Times filed its report. “Dixie Reigns Supreme,” the headline blared. “This city has simply gone wild over Jefferson Davis.” Davis was welcomed by a “tumultuous crowd that shouts itself hoarse.” The Times could not understand the symbolism: “The explanation of all this is not easy. There are other incidents as strange and perplexing as those already outlined. The leaders of the throng tell you that it means nothing; that it is but a passing show to please their old chieftan, a day of sound and fury, signifying nothing. It is all a conquered people can offer him…it is useless to wonder how much more there is stored up in their hearts.”

From the moment he arrived, women flocked to his side, praising him, teasing him, and flirting with him. Some soothed him with fans. They filled his room at the Exchange Hotel with roses. One woman who shook his hand exclaimed, “I am more of a rebel right here than ever before.”

Davis’s old friend Virginia Clay witnessed some of these encounters: “I saw women shrouded in black fall at [Davis’s] feet, to be uplifted and comforted by kind words. Old men and young men shook with emotion beyond the power of words on taking [his] hand.”

That night, when Davis spoke at the old capitol, the mayor introduced him as the representative Southern man: “It is with emotions of the most profound reverence that I have to introduce you to that most illustrious type of southern manhood and statesmanship—our honored ex-president, Jefferson Davis.”

Davis rose and began to speak. His lips moved, but no one could hear him. The sound of thousands of cheering voices drowned him out. “A cheer long pent up since 1861 rent the air, was taken up by the crowds on the streets, and echoed and re-echoed all over the city,” reported one paper. Davis bowed to his right and left and tried to make himself heard above the roar.

“Brethren,” he cried, in that same clear, pleasing, distinctive voice that had once charmed Varina the day they met, and that had thrilled listeners when he spoke on the floor of the U.S. Senate. That single word—“brethren”—incited the throng to shout even louder. Women stood on their chairs and, weeping and laughing from joy, flapped their handkerchiefs in the air like the wings of birds, or like little signal flags.

In his seventy-eight years, Davis had never seen anything like it, not even on the day when, twenty-five years ago, he was inaugurated the Confederacy’s president. The audience silenced itself and allowed him to speak.

“My friends,” he began, “it would be vain if I should attempt to express to you the deep gratification which I feel at this demonstration; but I know that it is not personal, and therefore I feel more deeply grateful, because it is a sentiment far dearer to me than myself.” With those words, Davis reminded his listeners that he did not return to the first capital of the Confederacy to claim honors for himself, but to tender honors to others—the Confederate dead. “You have passed through the terrible ordeal of a war which Alabama did not seek…a holy war…Well do I remember seeing your gentle boys, so small, to use a farmer’s phrase, they might have been called seed corn, moving on with eager step and fearless brow to the carnival of death; and I have also looked upon them when their knapsacks and muskets seemed heavier than the boys, and my eyes, partaking of a mother’s weakness, filled with tears. Those days have passed. Many of them have found nameless graves…” The poetic image of the “seed corn” that never grew to maturity broke the hearts of the parents of those boys. Davis, the old master orator of the U.S. Senate, still knew how to read a crowd. His audience was on the verge of a frenzy.

Then Davis uttered the words that forever more united past and present through the dream of the Lost Cause. “But they are not dead—they live in memory and their spirits stand out a grand reserve of that column which is marching on with unfaltering steps towards the goal of constitutional liberty.” Davis transported his listeners back to the beginning of the Civil War:

I am standing now very nearly on the spot where I stood when I took the oath of office in 1861. Your demonstration now exceeds that which welcomed me then…the spirit of Southern liberty is not dead. Then you were full of joyous hope, with a full prospect of achieving all you desired, and now you are wrapped in the mantle of regret…I have been promised, my friends, that I should not be called upon to make a speech, and therefore I will only extend my heartfelt thanks. God bless you, one and all, men and boys, and the ladies above all others, who never faltered in our direst need.

His remarks done, Jefferson Davis sat down.

What happened next stunned the reporter from the Atlanta Constitution. “Such a cheer as followed the speaker to his seat cannot be described,” he noted. “It was from the heart. It was an outburst of nature. It was long continued. Mr. Davis got up again and bowed his acknowledgments. Men went wild for him; women were in ecstasy for him; children caught the spirit and waved their hands in the air.” Then a lone Confederate veteran shouted, “Hurrah for Jeff Davis!” as loud as the old rebel could yell and within moments, thousands of voices repeated the salute.

The Atlanta Constitution reporter followed Davis back to the Exchange Hotel, and later wrote: “Your correspondent, presuming upon a previous acquaintance formed in Brierfield, called upon the noble old Mississippian in his room. He was greeted by a grasp of the hand which proved that Mr. Davis still had a good grip…he expressed himself as in the best of health for one of his years, and judging from his face, in the best of spirits.” A procession of well-wishers, starting with the mayor, interrupted the interview. Soon admiring and swooning women filled the former Confederate leader’s room.

Davis left Montgomery on April 29, but he did not go home to Beauvoir. He had accepted an invitation to go to Atlanta and speak there at the dedication of a sculpture of Ben Hill. Frank Burr wrote, “At every station along the route from Montgomery Mr. Davis was met by tremendous delegations, who shouted and cheered from the moment the train came in sight until it was out of hearing.” Burr penned an extravagant speculation: “All the South is aflame…and where this triumphant march is to stop I cannot predict.” When Davis arrived in Atlanta, he found fifty thousand people waiting for him at the railroad depot. Eight thousand children lined the route—more than a mile—from the station to the home of his host, his old friend Ben Hill. Two thousand Confederate veterans followed Davis’s carriage. Every business closed its doors except for the U.S. Post Office. The authorities in Washington had refused to permit it. At the dedication of the statue on May 1, newspaper editor Henry Grady gave Davis a stirring introduction: “This outcast…is the uncrowned king of our people…the resurrection of these memories that for twenty years have been buried in our hearts, have given us the best Easter we have seen since Christ was risen from the dead.”

Next, Davis traveled by train to Savannah, where he would attend the centennial of a local militia unit, the Chatham Artillery, and participate in the unveiling of two bronze tablets on the monument to the Revolutionary War hero General Nathaniel Greene. This simple forty-foot marble shaft, “the first monument ever erected in the South to a Northern man,” said the New York Times, had stood in the public square forty years barren of inscriptions. To celebrate the Chatham Artillery, the Georgia Historical Society offered to attach the tablets. The train sped three hundred miles from Atlanta to Savannah, making, by one hour, the fastest time ever recorded between those two cities. The five-car train was decorated with rich bunting, and nailed to each side of the train in large letters was the motto: “He was manacled for us.” At the end of Davis’s car, the last one, his portrait, captioned “Our President” in flowers formed into the shape of letters, delighted onlookers. Along the tracks, people gathered to watch the train fly by. At every platform, crowds thronged. When the rain stopped at Macon for twenty minutes, Davis spoke of being brought here as a prisoner twenty-one years earlier.

Davis arrived in Savannah that evening for a four-day visit. The streets were impassible. “As in Atlanta,” the New York Times reported, “flowers were rained upon him from the multitudes.” It was a triumphant return to the city from which Davis had been sent by sea to his captivity in May 1865.

By his second day in Savannah, Davis began to lose his strength. The tour had exhilarated him, but he was also exhausted by the travel. The New York Times reported on his weakened condition:

He is beginning to feel the effects of the demands which his people have made upon his waning strength, as well as those which he himself has imposed. The kindly expressions and demonstrations…have warmed his heart, so that he wants to meet whatever exactions in the way of speechmaking or handshaking are asked of him. When he started, a week ago, he was reluctant to speak more than a few words of thanks…Since then his disposition has changed completely, and he submits himself willingly to the calls from the shouting multitudes for speeches. “Do they want me?” he asked several times yesterday as he lay in his couch in the railway car and heard the rousing cheers at several stations. “All right,” he would continue; “tell them I’m coming.” And then, taking his stout cane in hand to aid his frail steps, he would walk slowly out to the platform and talk.

By that night, Davis had regained his strength and he spoke to more than ten thousand people from the steps of the Comer residence.

That night was another triumph, but it was also the end of the tour. Davis had not planned it, but he had enjoyed it. When it began, he was not sure that anyone would want to see him again. When it ended, he knew he held a place in Southern hearts.

It was no surprise that the next year, in October 1887, he agreed to return to Macon, which had been but a brief stop during the first tour to attend a Confederate reunion and the Georgia State Fair. This time Varina accompanied him. She marveled at the reception, but worried that it would kill him. A newspaper article warned citizens that this was Davis’s “last journey,” and that they must do nothing to tax his feeble strength, not even shake his hand. He was seventy-nine and weaker than he had been the previous year. When Varina cautioned him that he might die during the visit, Davis retorted: “If I am to die it would be a pleasure to die surrounded by Confederate soldiers.”

Several thousand of them did surround him when they charged the house where he was staying. It was like Pickett’s Charge all over again. When they produced a battle flag, David said: “I am like that old flag, riven and torn by storms and trials. I love it as a memento; I love it for what you and your fathers did. God bless you! I am glad to be able to see you again.” Then Davis took the flag and waved it through the air. The veterans went wild.

At the climax of the visit, Jefferson and Varina presided over Children’s Day at the fair. Beginning with the orphans, the Davises blessed and laid hands upon several thousand children. It was as though, by his touch, he sought to pass on the values of the Lost Cause to a new generation. He returned to Beauvoir, confident that he had made his last public appearance.

In March 1888, Davis accepted an invitation to speak to an audience of young men in Mississippi City, Mississippi. He was prepared to decline, but accepted because the venue was not far from Beauvoir, and the composition of the audience appealed to him. It turned out to be one of the shortest—and one of the most remarkable—speeches of his life:

Mr. Chairman and Fellow Citizens: Ah, pardon me, the laws of the United States no longer permit me to designate you as fellow citizens, but I am thankful that I may address you as my friends. I feel no regret that I stand before you this afternoon a man without a country, for my ambition lies buried in the grave of the Confederacy. There has been consigned not only my ambition, but the dogmas upon which that Government was based.

Davis sounded like he was about to indulge in bitter sectionalism. But then he changed his tone:

The faces I see before me are those of young men; had I not known this I would not have appeared before you. Men in whose hands the destinies of our Southland lie, for love of her I break my silence, to speak to you a few words of respectful admonition. The past is dead; let it bury its dead, its hopes and its aspirations; before you lies the future—a future full of golden promise; a future of expanding national glory, before which all the world shall stand amazed. Let me beseech you to lay aside all rancor, all bitter sectional feeling, and to make your places in the ranks of those who will bring about a consummation devoutly to be wished—a reunited country.

Davis reached a milestone on June 3, 1888—his eightieth birthday. He had been inaugurated president of the confederacy twenty-seven years ago; the Civil War had ended twenty-three years ago, and he had survived Abraham Lincoln by the same measure of time; and he had been a free man for the last twenty-one years. Lincoln was only fifty-six when he was assassinated, and he had no time to savor his victory. Davis had almost a quarter century to reflect upon his defeat. From all across the South, from people high and low, congratulations and gifts poured in to Beauvoir. From the state of Mississippi came the gift of a crown, this one fashioned not from thorns, but silver.

One letter, from a former Confederate soldier of no prominence and unknown to Davis, spoke for all the anonymous, faithful veterans who had survived the war.

Lewisville, Arkansas

June 3d. 1888

Hon. Jefferson Davis

Beauvoir, Miss.

My dear Sir:

Permit me to cordially congratulate you upon becoming an octogenarian. As a native of Ponotoc, Miss., and as an ex-confederate, who entered the army at 17 years of age and remained till the last gun had fired, may I not claim a few moments of your time by tendering to you my congratulations on this your eightieth birthday? May Divine Providence bless you with good health and unalloyed happiness.

Many thousands of the old soldiers yet live to congratulate you…but many thousands, in the past two decades, have passed over the river…and they, and the grandest of all armies, our fallen heroes, with those grand commanders, Lee, Johnston and Jackson, are awaiting the arrival of their Commander in chief. All of us are indeed proud that you have been permitted to remain with us until the ripe age of eighty and we pray earnestly that you may be permitted to enjoy many more years of health, happiness and prosperity…My heart goes out to you in your declining years as warmly as when it was beating to the martial tread upon the fields of battle.

…I beg you to pardon me for imposing this long letter upon you. I only intended to express to you my joy upon your attaining your 80th birthday—and wishing you a longer life with us, and greater happiness in the beautiful life “over there”…

With an earnest prayer for your welfare, I am, with great respect,

Yours truly—

W. P. Parks

Dr. Harker’s patent medicine company, manufacturers of “the only true iron tonic” that “beautifies the complexion” and “purifies the blood,” published a handsome advertising card bearing Davis’s image, implying that the venerated former president owed his longevity to its dubious concoction.

In December 1888, former confederate general Jubal Early, a favorite of Davis, visited Beauvoir. He noticed Davis’s threadbare clothes and offered to buy him a new suit. No, Davis demurred, he could not accept such generous charity, but he would be willing to accept just the fabric. He would pay his own New Orleans tailor, Mercier, who still kept his measurements on file, to fashion the garment. Early ignored him. He bought the wool and instructed Mercier to cut a simple, elegant suit. It was a fine garment of Confederate gray.

In 1889, Davis received an unexpected communication that jolted him back a half century in time to his youth. A woman from the North, Miss Lee H. Willis, wrote to him from the town of Richview, in Washington County, Illinois. She had discovered an old, lost love letter from him to Sarah Knox Taylor. Would he like it returned to him? The inquiry resurrected long-buried memories from his remote past. He remembered the letters that Knox had written to him, a romantic correspondence lost for decades. Oh yes, “you rightly suppose it has much value to me,” he replied in a letter to Willis dated April 13, 1889: “The package containing all our correspondence was in a writing desk, among the books and papers I left in Mississippi when called to Alabama [in 1861 as president], and it would be to me a great solace to recover the letters Miss Taylor wrote to me, and which were with the one you graciously offer to restore.”

Memories fifty years old rushed back to him, of the girl he once wrote in December 1834: “Dreams my dear Sarah we will agree are our weakest thoughts, and yet by dreams have I been lately almost crazed, for they were of you…I have read…your letter to night. Kind, dear letter, I have kissed it often…Shall we not soon meet Sarah to part no more? Oh! How I long to lay my head upon that breast which beats in unison with my own, to turn from the sickening sights of worldly duplicity and look in those eyes so eloquent of purity and love.” Davis never found the package of lost letters he’d hoped to recover.

Knox Taylor was not the only memory stirring inside Davis. He brooded over many things. “The shadow of the Confederacy,” Varina confided to her friend Constance Cary Harrison, “grows heavier over him as the years weigh his heart down.” Now, she wrote, “he dwells in the past.”

In November 1889, Davis departed Beauvoir alone for one of his periodic trips to inspect his lands at Brierfield, and he became ill during the trip. It was his lungs, with complications from his lifelong foe, malaria. He was rushed to New Orleans, where Varina, summoned by an emergency telegraph, joined him. Through newspaper reports, the whole South kept a vigil at his bedside. For a time Davis rallied, then declined. Near the end, when Varina

THE TWILIGHT YEARS AT

BEAUVOIR.

raised more medicine to his lips, he declined: “I pray I cannot take it.” He fell asleep, and shortly after midnight, on December 6, 1889, he died peacefully in his bed, his wife’s hands folded into his.

It was nothing like the death of Abraham Lincoln, which was unexpected, sudden, violent, bloody, and when he was in his prime. Neither Lincoln, nor his family, nor the people had time to prepare for it. Lincoln had no time to say good-bye. He enjoyed no final, long look back to recall his life and tally his deeds. Jefferson Davis was granted this privilege. He enjoyed the gift of years to live, to write, and to reflect. He had fallen and yet lived long enough to rise again. And the people of the South had nearly a quarter of a century to prepare themselves for his death. Davis had the chance to review his life in full, and to retrace his journey to the beginning.

For Lincoln, the end was only darkness. But in one way their deaths were the same. Just as April 15, 1865, symbolized to the North more than the death of just one man, so too the death pageant that followed December 6, 1889, was not for Davis alone.

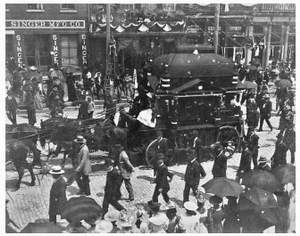

JEFFERSON DAVIS IN DEATH, NEW ORLEANS, DECEMBER 1889.

After Davis was embalmed, while he lay in state, a photographer set up his camera and lights to take pictures of the corpse. But there would be no repeat of the scandal that had occurred after Lincoln’s remains had been photographed in New York City in April 1865. Varina had given permission for one photographer to make several dignified images of her husband’s body, and she allowed at least one print to appear in a memorial tribute volume published by a trusted friend and longtime supporter, the Reverend J. William Jones. These photos of Davis’s corpse, taken much closer to the body, and offering far greater detail than Gurney’s images of Lincoln, captured Davis in elegant repose, dressed in the coat of Confederate gray that Jubal Early had given him, and clasping in his folded hands sheaves of Southern wheat. His lips formed a faint, subtle smile. Varina also consented to a death mask, an application of wet plaster to the deceased’s face that would result in a perfect, life-size, three-dimensional likeness of Davis’s visage. Edwin M. Stanton had not allowed a death mask of

Abraham Lincoln—it was too morbid and disrespectful, he might have reasoned. For Davis, it would be a necessary artifact for the many monuments his supporters intended to build in his honor. Lincoln’s two life masks, made in 1860 and 1865, had proven priceless for this purpose. So too would Davis’s death mask.

In Washington, the government of the United States took no official notice of the death of Jefferson Davis. The mayor of New Orleans had sent a clever telegram notifying the War Department of the death of, not the former president of the Confederate States of America, but of a former secretary of war of the United States. Protocol dictated that the department fly its flag at half-staff and close for business. But Secretary of War Proctor declined to recognize the passing of Davis, and he refused to lower the American flag. If federal authorities refused to take notice of the death of the former cabinet officer, that did not deter at least one sympathetic private citizen in the nation’s capital from mourning the Confederate president. On Capitol Hill, across the street from the Watterston House, home of the third librarian of Congress, and a local landmark visited by Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and other luminaries, blatant symbols of mourning adorned a town house, causing a local sensation. The Washington Post reported the unusual occurrence:

A STRIP OF BLACK CLOTH. A Washington Lady Shows Her Grief at Jeff. Davis’ Death. Probably the only outward evidence of sympathy for “the lost cause” and tribute to the memory of Jefferson Davis to be seen in this District is to be found at No. 235 Second Street southeast, occupied by Mrs. Fairfax. The shutters of the house are all closed and the slats tightly drawn while running across the entire front of the house, between the windows of the first and second floor, is a broad strip of black cloth looped up with three rosettes—red, white, and red. Mrs. Fairfax is known to have been an ardent supporter of the Confederate cause, and married State Senator Fairfax, of Fairfax County, Va. During the war of the rebellion she gave all the assistance to the South possible, and repeatedly crossed the lines, carrying to the Confederates both information and substantial assistance. It was through knowledge obtained by such expeditions as this that leaders of the Confederate side were enabled to anticipate movements of the Union armies and in a number of instances checkmate them. The house on Second street yesterday attracted more attention, probably, than ever before, and the emblems of mourning were the cause of considerable comment among the neighbors and travelers on that street.

In Alexandria, Virginia, where George Washington had kept a town house, where slave pens and markets once flourished, where Colonel Elmer Ellsworth was killed twenty-eight years ago, and where Lincoln’s funeral car was built in the car shops of the United States Military Railroad, the sounds of mourning rose above the city and echoed over the national capital. Old Washingtonians remembered when the bells had tolled for Lincoln. Now they heard them toll for Jefferson Davis.

There was a magnificent funeral in New Orleans, a huge procession just like the one in Washington for Lincoln, and Davis was interred at Metairie Cemetery. But on the day Davis was buried, everyone knew this was only a temporary resting place. It was understood that Varina Davis would in due course select a permanent gravesite elsewhere. Several states, including Mississippi, vied for the honor. In 1891, Varina stunned Davis’s home state. She vetoed its proposal and chose Virginia. Davis would return to his capital city, Richmond.

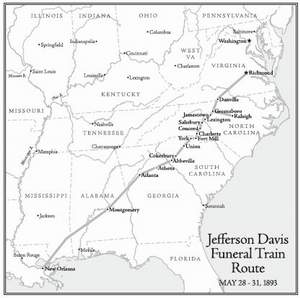

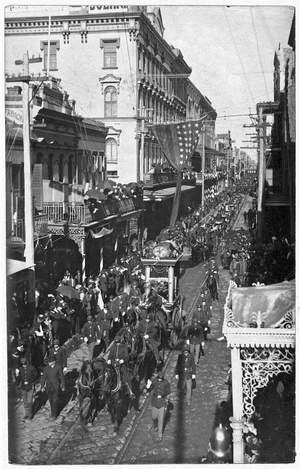

On May 27, 1893, almost three and a half years since Davis’s death, his remains were removed from the mausoleum at Metairie Cemetery. A hearse carried his coffin to Camp Street, to Confederate Memorial Hall, a museum crammed with oak and glass display cases filled with Civil War guns, swords, flags and relics. From 5:00 P.M. on the twenty-seventh until the next afternoon, Davis lie there in state. Then a procession escorted his body to the railroad station, where it was placed aboard the train that would take him to Richmond. Like Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train, the one for Jefferson Davis that left New Orleans on May 28 did not rush nonstop to its destination. First it paused at Beauvoir, where waiting children heaped flowers upon the casket. The train stopped briefly at Mobile shortly after midnight on May 29 to change locomotives, then stopped at Greenville, Alabama, at 6:00 A.M. People lined the tracks, and wherever the train halted, mourners filled Davis’s railroad car with flowers.

Arriving in Montgomery during heavy rains early on the morning of May 29, the train was met by fifteen thousand people. For the first time since Davis’s remains left New Orleans, they were removed from the train. A procession escorted the hearse to the old capitol, where in 1886 he experienced his great resurrection. While Davis lie in state in the chamber of the Alabama supreme court, bells tolled and artillery boomed. A large banner reminded mourners that “He Suffered for Us.” To anyone who remembered the Lincoln funeral cortege, the sight of another presidential train winding its way through the nation, its passage marked by crowds and banners, and by the scent gunpowder and flowers, the experience was familiar and eerie. Floral arches erected in towns along the route of Davis’s final journey proclaimed “He lives in the Hearts of his People.” Once, identical words greeted Lincoln’s train.

Davis’s train reached Atlanta at 3:00 P.M. on May 29, and forty thousand people passed by his coffin. The train pushed on through Gainesville, Georgia; Greenville, South Carolina; and then into North Carolina, where it passed through Charlotte, Salisbury, Greensboro, and Durham. All along the way, people built bonfires, carried torches, rang bells, and fired guns to honor the esteemed corpse. At Raleigh, the coffin was removed again, placed in a hearse, and paraded through town. After lying in state there, Davis was taken to Danville, Virginia, his first refuge after he left Richmond the night of April 2, 1865.

The funeral train arrived in Richmond at 3:00 A.M. on May 31. In the middle of the night, a silent procession escorted the coffin from the station to the state capitol. Artillery fire woke the city later that morning, and twenty-five thousand people, including six thousand children, passed by his casket. At 3:30 P.M. a grand procession escorted his remain to Hollywood Cemetery. There, a simple gravesite ceremony and a bugle playing taps ended his last journey.

In preparation for this day, word was sent to Washington, D.C., to Oak Hill Cemetery, where workers opened a small grave that had gone undisturbed since 1854, almost forty years before. The body of Samuel Davis was brought to Richmond to rest by his father. And

THE RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA, FUNERAL PROCESSION,

ON THE WAY TO RICHMOND.

in Hollywood Cemetery, another grave was opened so that Joseph Davis, buried in 1864, could rest beside his father too.

Jefferson Davis had survived Abraham Lincoln by twenty-four years. Now, his journey also done, he joined him in the grave.

For several years after Davis’s reburial, efforts to raise a memorial to him in Richmond floundered. The Jefferson Davis Monument Association, organized in 1890, had, in collaboration with the United Confederate Veterans, been confounded by disagreements about the location, artist, cost, and design of the monument. Finally, in 1893, 150,000 people attended the laying of the cornerstone. Fifteen thousand Confederate veterans marched in the parade. Then the project stalled again, and in 1899 the men of the UCV admitted defeat and handed the task over to the women of the South, who had founded the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

Adopting the motto “Lest we forgot,” the UDC rolled out a strategic and passionate campaign to raise the necessary funds. Not only had Davis been the chief executive and chosen leader of the Confederacy, exhorted the UDC in a fund-raising letter, “he was our martyr, he suffered in his own person the ignominy and shame our enemies would have made us suffer. This was thirty-five years ago, and his monument is yet to be built. The women of the South have solemnly sworn to wipe out this disgrace at once.”

The campaign worked. As the money rolled in, the women beseeched the famous Southern sculptor Edward Valentine, renowned for his bronze bust of Robert E. Lee and also his Lee sculpture in the chapel at Washington and Lee University, to design the Davis monument and its companion sculpture. In 1907, fourteen years after Davis’s reburial in Richmond, his monument was ready. On April 16, Confederate veterans, aided by three thousand children, pulled on two seven-hundred-foot ropes and dragged the eight-foot-tall bronze of Davis along Monument Avenue. Dedication day was scheduled for June 3, Davis’s ninety-ninth birthday, and the climax of a major, weeklong Confederate reunion in the city.

Two hundred thousand people stood along the parade route from the capitol to the monument, more people than had lined Pennsylvania Avenue for Abraham Lincoln’s funeral procession. An additional 125,000 people gathered near the monument. After an address by Virginia governor Claude A. Swanson, Margaret Hayes, Davis’s sole surviving child, unveiled her father’s sculpture. Cannon fired a twenty-one-gun salute, an honor traditionally reserved for the president of the United States. Behind the bronze figure of Davis, his right arm outstretched and pointing to the old capitol of the Confederacy, there arose a sixty-foot-tall column topped by a female figure, Vindicatrix. Three mottoes adorn the base: “Deo Vindici” (the motto on the wartime Great Seal of the Confederacy); “Jure Civitatum” (for the rights of the states); and “Pro Aris Et Focis” (for hearth and home). Below the bronze figure a tablet bears the dedication: “Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate Sates of America, 1861-1865.”

After the ceremonies were over, the greatest crowd that had ever assembled in his name went home.