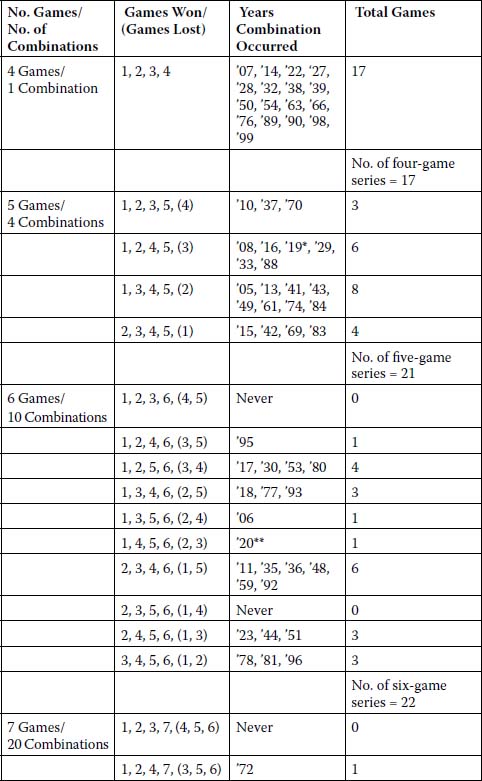

There are thirty-five ways of winning a World Series (i.e., there are thirty-five possible combinations of wins and losses in a World Series).1 Seven of these—two six-game combinations and five seven-game combinations—have never occurred.

For example, the seven-game combination in which the winning team wins games one, two, six, and seven and loses games three, four, and five has occurred twice (Minnesota’s victories in 1987 and 1991). Note, incidentally, that the one, two, six, and seven combination we use as an example is the only one in which a team lost any three consecutive games and won the series (i.e., no team has won a series by winning games one, two, three, and seven (and losing four, five, and six); by winning one, five, six, and seven (and losing two, three, and four); or by winning four, five, six, and seven (and losing one, two, and three).

It is interesting to compare the percentages of 4-, 5-, 6-, and 7-game World Series with what would be expected in a “coin-toss series.”

A coin-toss series is one played by two teams identically matched in every way, who play on a neutral field, and are unaffected by previous games; in other words, neither team has any advantage. The two teams are a “heads” team and a “tails” team, with the former winning if the coin lands heads and the latter winning if the coin lands tails. The series is won by the team that first wins four tosses.

One might suspect that, because in a real World Series one team is often better than the other, the series would tend to be shorter than the coin-toss series with their equally matched teams.

The cynic, on the other hand, might expect the players in the real World Series to stretch the series to increase profits. (Players only share in the receipts for the first four games, but it does not take that much cynicism to wonder whether the increased owners’ profits from a longer series might not indirectly profit the players.)

To compare the real World Series to a coin-toss series one must, of course, calculate the expected lengths of coin-toss series. To do this, one does not, as would seem reasonable, base the calculation of probabilities on the thirty-five real possibilities listed in the table above on pages 52 through 53. The most common error in probability assessment is forgetting that a calculation of probabilities must be based on equally likely possibilities. The thirty-five real possibilities are not equally likely.

There are 128 equally likely sequences of wins and losses (heads and tails) in a seven-game series. Ninety-three of these cannot happen in a real World Series (e.g., W, W, W, W, L, L, L), but they are counted when figuring probabilities. (The 128 is 27, or 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2; each 2 represents a game in which a team can win or lose.)

Thus, the expected probabilities in the coin-toss series (rounded to nearest full percentage point) are

13%—about one in eight—of the coin-toss series will be a four-game series.

25%—about one in four—of the coin-toss series will be a five-game series.

31%—about one in three—of the coin-toss series will be a six-game series.

31%—about one in three—of the coin-toss series will be a seven-game series.

How does this compare with the real World Series (rounded to nearest full percentage point)?

18% (17 of 95; about one in six) of real World Series have been a four-game series.

22% (21 of 95; about one in four-and-a-half) of real World Series have been a five-game series.

23% (22 of 95; about one-in-four-and-a-half) of real World Series have been a six-game series.

37% (35 of 95; about four-in-ten) of real World Series have been a seven-game series.

The only really significant divergence from randomness is the fewer six-game series and greater number of seven-game series than would be expected if skill, home advantage, and so on, played no role. This is probably owing primarily to the human factor: the one who is threatened with being eaten fights harder than the one anticipating the meal.

There is, however, an important additional reason: one team has a 3–2 advantage in home games in the first five games, and this is evened up in the sixth game. The team that is home in the sixth game is more often the team that is down, rather than up, 2–3, and home teams win more often than they lose. Therefore, the probability of a series going to the seventh game if it reaches the sixth is greater than the 0.50–0.50 of the coin toss. (Home teams down 2–3 have won sixth games nearly twice as often as they have lost them because the present configuration of home and away games was introduced.)

It is an axiom of contemporary science that there is no a priori knowledge of the world.

Some aptitudes may require no empirical experience (i.e., human beings clearly have the ability to distinguish one thing from another; if everything looked the same to an infant, there would be no possibility of human development.) However, discovery of facts about the world always require at least an initial empirical observation (from daily life or formal experiment). (That is, the aptitude to make distinctions does not become knowledge that there are distinctions in the real world until the infant observes the real world.)

In other words, science cannot be deductive in the way mathematics can. Mathematics defines its own world. Thus, if A is a real number greater than B and B is a real number greater than C, A is greater than C. There is no need of empirical observation because A is defined as being greater than B, and B is defined as being greater than C. Note that what would rule this out as science is not our deducing logically that A is greater than C, but the absence of even an initial observed empirical fact.

This point is important because people occasionally—when distinguishing the (deductive) logic of mathematics from the inductive logic of science—understate the importance of deductive logic’s ability to discover new facts. In reality, it is very often the case that we learn new facts through deduction from known—empirically discovered—old facts. (This is because at least one initial fact must be known from empirical observation that this is science, not mathematics.)

Let us take an example from everyday life, assuming that we all know that the World Series is won by the first team to win four games and that the first, second, and, if they are necessary, sixth and seventh games are played in one team’s ballpark, while the third, fourth, and if it is necessary, fifth game are played in the other team’s ballpark.

Note that the above information does not represent discovered facts but our construction of a World Series, something approaching a definition more closely than a discovered fact. Which team is home in which game is more a rule than a fact. Note also that we can deduce from our construction that a series must go the full seven games for a team to lose any three consecutive games and win the series and that it must go the full seven games for the home team to win every game.

Now, following the 1987 World Series, the newspapers reported what we will call

Fact One: This was the first World Series in which every game was won by the home team.

To know this fact the newspaper men had to look to the reported observation of empirical reality (i.e., the record book); there is no purely logical way to know that no team had previously won the World Series by winning its four home games.

“So what?” you may well be asking at this point. The “so what” is this: when going to the record book, an astute reporter could have noticed

Fact Two: No team had ever lost any three consecutive games and won the World Series.

Fact two is superior to fact one in that (a) it is more general and (b) it permits one to logically deduce fact one. It is more general because it tells us not merely that before 1987 no team had won games 1, 2, 6, and 7 (the only way a team can win by winning its home games), but also that no team ever won a World Series by winning games 1, 2, 3, and 7 or 1, 5, 6, and 7 or 4, 5, 6, and 7. Thus, for example, fact two tells us that no team has ever won a World Series by winning all of its away games (which also requires winning games 1, 2, 6, and 7).

Fact two tells us more about reality than fact one while also telling us fact one.

Fact one does not permit us to logically deduce fact two. The fact that 1987 was the first time that the home team won every game does not tell us that it had never been the case that the away team won every game or that no team had won the World Series by winning games 1, 2, 3, and 7 or 1, 5, 6, and 7 or 4, 5, 6, and 7.

We’re not talking e = mc2 here, but we are talking about the same relationship of logic and science. We live in the same physical universe that Einstein did, and we can learn about that physical universe only through the same logic and science that Einstein did.

British author Simon Singh, who specializes in writing about mathematics and science, in his excellent Fermat’s Enigma gives a wonderful example of the difference between the deductive method of mathematics and the inductive method of science.

Picture a regular chess board or checkerboard with two opposing corner squares cut off the two opposing white squares. This leaves 32 white squares and 30 black squares. Now take 32 dominoes, each the size and shape of two squares. (Ignore the numbers on the dominoes; they are irrelevant.)

Here is the question: can you place the 32 dominoes on the board in such a way that the board is exactly covered? (A domino must cover two squares exactly, so it cannot be cut in two or placed on two diagonally touching squares.)

The scientific method of doing this would be to test a good number of combinations and, finding that none of them precisely covered the board, tentatively conclude that it is impossible to do so. But this would never give certainty because someone might subsequently find a combination that does the trick.

The mathematical method is this:

Note that the two removed opposing corners were the same color (as they had to be; whether the two were both white or both black does not matter).

Note that no two (nondiagonally) adjacent squares are the same color.

Each domino must cover two adjacent squares.

Therefore, the first 30 dominoes cover 30 white squares and 30 black squares, leaving 2 black squares.

Thus, you are always left with 2 squares of the same color.

But the final domino must, like all the others, go on squares of two different colors (because it must go on adjacent squares, and adjacent squares are always two different colors)

Therefore, the 32 dominoes can never exactly cover the board.

It is not uncommon for mathematicians to find that a guess (a conjecture) or an educated guess (a hypothesis) turns out to be incorrect. It even occasionally happens that a proof whose conclusion is true is found to be faulty (i.e., not prove what it claims to be true.) In such cases, a later proof virtually always proves the conclusion.

What almost never happens is that a seeming proof turns out to be faulty and its conclusion turns out to be false. Marcus du Sautoy, professor of science and mathematics at Oxford, gives an example that comes close. The French mathematician Augustin-Louis Cauchy believed he had a proof that all geometric solids satisfied a certain equation. It turned out that Cauchy’s equation failed for a cube with a hole in its center.

I know what you are thinking: So Cauchy did have a proof for solids without holes, and if a solid has a hole it is not a solid. No mathematician buys this, and, anyway, a proof that covered solids with holes was soon discovered.

While there are various views of precisely what probability is, and while probability on a quantum level is a property of nature herself, in practical terms, probability is usually a measure of ignorance. Consider, for example, your chance of guessing the suit of the bottom card in a deck. It is one in four.

But now consider the situation if you get a peek at the bottom card—just enough of a peek to see that it is black. You now know that the suit must be a spade or a club, so your chance of guessing the suit is one in two. The only thing that has changed is your ignorance, which has been cut in half.

Remember those 15 Puzzles you played as a kid? They were small, black-and-white square things with fifteen small squares numbered one to fifteen (in consecutive order) and one empty space. You could slide the numbered squares around to make different combinations of numbers.

You may remember that the companies that made the puzzles offered tremendous prizes to anyone who could move the pieces around and end up with certain combinations. You never could manage to get these combinations. But it was not your fault. They were impossible.

You would have saved a lot of time if you had known the simple way of finding out whether a combination was possible.

Count the number of times a number is followed by a lower number until a higher number is reached. So, for example, the desired combination is 15-14-13-12-11-10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1. This combination is possible because there is an even number (14) of decreases. Now consider 1-15-2-14-3-13-4-12-5-11-6-10-7-9-8. This is impossible because there is an odd number (7) of decreases.

It had been suspected for centuries that no map on a flat surface required more than four colors for every district (i.e., country, state, etc.) to have a different color from any bordering country. We refer here not just to a map of the real world, but a map of any possible configurations of countries (as long as no country or state is—like Michigan—divided into two or more separate parts and no countries meet at only a single point).

However, as of 1976, no one had been able to prove that there could not be a configuration requiring five colors. Then, in 1976, Wolfgang Haken and Kenneth Appel, colleagues and mathematicians at the University of Illinois, discovered a proof—a proof that required twelve hundred hours of computer time. This proof required some brilliant mathematics in addition to the computer time, but words cannot describe how much mathematicians despise it. The proof cannot be checked by a mathematician in a hundred lifetimes (except by rerunning the programs). In other words, the four-color proof is a bit lacking in the snappy elegance of Euclid’s proof of an infinity of primes.

A river divided the city of Konigsberg. In the river were two islands. Island A had a bridge to Island B and a bridge to each bank. Island B had the bridge to Island A and two bridges to each bank.

For many years the residents of Konigsberg added interest to their Sunday strolls by attempting to cross every bridge once and only once. (It was not necessary to end the stroll at the starting point.) No one accomplished the task, but some residents kept trying.

Had they consulted the great mathematician Leonhard Euler they could have saved a lot of shoe leather. Consider that the three bridges of Island A could be crossed in four ways:

1.Cross all three bridges by walking toward Island A.

2.Cross all three bridges by walking away from Island A.

3.Cross two bridges by walking toward Island A and one bridge by walking away from Island A.

4.Cross two bridges by walking away from Island A and one bridge by walking toward Island A.

Obviously 1 and 2 are impossible: you cannot walk to a place three times without walking away from it, and you cannot walk away from a place three times without walking to it.

Choices 3 and 4 are each possible, but because the number of bridges of Island A is odd (i.e., three), the stroll must either begin (4) or end (3) at Island A.

Now consider one of the two banks of the river. It also has three bridges, so the stroll must either begin (4) or end (3) on this bank.

Fine. The stroll might begin on Island A and end on the bank or begin on the bank and end on Island A.

But wait. The other bank also has three bridges. The stroll must begin or end here too. Because the stroll cannot begin at two different places or end at two different places, the stroll is impossible. If one more bridge were appropriately added (which, in fact it has been), the stroll would be possible.

In general, whatever the number of “points” (in this case islands and banks) and paths or “lines” (in this case, bridges), you can cover all paths without retracing your steps only if the number of points (in this case, islands and banks) at which an odd number of paths meet is 0 or 2.

Since ancient times, many people have attempted to solve the following three problems using the tools of Euclidian geometry, invoking only straight lines and circles or parts of circles and using only a straightedge and a compass:

1.Doubling of the cube: create a cube with sides double that of a given cube.

2.Trisection of an angle: divide an angle into three equal angles.

3.Square the circle: create a square with the same area as a given circle.

You would be better off spending your time training a cow to jump over the moon. We do not know that there could never be a cow that can jump over the moon. We do know that the above problems cannot be solved. There are proofs that they are unsolvable.

Okay, okay. You want one standard logic puzzle. Here is a classic. About 2 or 3 percent get this one right within ten minutes. It has no “catch” and is particularly elegant in that every fact given is necessary.

On a train, Smith, Robinson, and Jones are the fireman, brakeman, and engineer, but Smith is not necessarily the fireman, Robinson is not necessarily the brakeman, and Jones is not necessarily the engineer. Also on the train are three businessmen: Mr. Smith, Mr. Robinson, and Mr. Jones. We know these facts:

1.Mr. Robinson lives in Detroit.

2.The brakeman lives exactly halfway between Detroit and Chicago.

3.Mr. Jones earns exactly $20,000 dollars a year.

4.The brakeman’s nearest neighbor, one of the passengers, earns exactly three times as much as the brakeman.

5.Smith beats the fireman at billiards.

6.The passenger whose name is the same as the brakeman’s lives in Chicago.

What are the names of the fireman, the brakeman, and the engineer?

While we will not consider this a brainteaser (it takes too long), the answer is given at the end of the book.

Over “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” “my true love gave to me” 364 gifts. (On the first day, my true love gave to me: 12 + 11 + 10 + 9 + 8 + 7 + 6 + 5 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 78. On the second day: 11 + 10 + 9 + 8 + 7 + 6 + 5 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 + 66, etc. 79 + 66 + … = 364.)

Here is a simpler way:

| Twelfth day: 12 + 11 + 10 … 1 | = 78 |

| Eleventh day: 78 minus the twelfth day’s 12 | = 66 |

| Tenth day: 66 minus the eleventh day’s 11 | = 55 |

| Ninth day: 55 minus the tenth day’s 10 | = 45 |

| … | |

| First day: 3 minus second day’s 2 | = 1 |

This problem has two rules:

1.When you have an odd number, triple it and add 1.

2.When you have an even number, halve it.

Now, select any positive whole number and proceed.

Say you select 6. Because 6 is even, halve it—giving 3. Because 3 is odd, triple it and add 1—giving 10. Because 10 is even, halve it—giving 5. Because 5 is odd, triple it and add 1—giving 16. Because 16 is even, halve it—giving 8. Because 8 is even, halve it—giving 4. Because 4 is even, halve it—giving 2. Because 2 is even, halve it—giving 1. Because 1 is odd, triple it and add 1—giving 4. Because 4 is even, halve it—giving 2. Because 2 is even, halve it—giving 1. Because 1 is odd, triple it and add 1—giving 4.

Notice anything? The sequence has entered an unending 4-2-1-4-2-1 … loop. “No big deal,” you say. How about this? The same is true for every positive whole number through 27,000,000,000,000,000. Is it true for every positive whole number over 1,000,000,000,000? No one has been able to prove it is or to find an exception. But it is not for a lack of trying.

As George G. Szpiro points out in his fascinating book The Secret Life of Numbers, if there is an exception, it must be a number greater than 27 quadrillion (i.e., 27 with fifteen zeros) and must have at least 275,000 steps before settling down to 1.

You may have been a bit dubious about the claim that 0.99999 … is the same as 1. But consider this: 0.33333 … plus 0.33333 … plus 0.33333 … equals 1/3 plus 1/3 plus 1/3, which equals 1.

You might think that there would be no practical application of mathematics more easily accomplished than this: a traveling salesman must visit thirty-three cities, and he needs to know the shortest route that gets him to every city at least once.

You saw way back on page 2 that not only can the mathematician not give you the shortest route, he cannot even tell you whether there is any way other than trial and error for finding the shortest route with certainty. And when there are more than a few cities, even a fastest computer using only trial and error would make for a hopeless task; fifty cities, for example, would have to check 1062, a task that would take millions of years. There are algorithms guaranteeing a route not more than a few percent longer than the shortest route.

This problem, the “packing-bin” problem discussed in Chapter 5, and a million other problems all resist the discovery of a practical algorithm. If an algorithm for even one of these problems were found, it would work for all of them. If it can be shown that there can be no efficient algorithm (see “Pack Those Bins,” on page 49) for even one of these problems, then there can be no such algorithm for any of them.

This simple equation has never been solved in positive integers, nor has anyone ever proved that there is a solution or that there is no solution (other than 0): (x + y + z)3 = xyz

You have to count to one thousand before the letter “a” is required to spell an integer.

You see an endless line of squares of concrete:

You toss a coin. Whenever it is heads, you go to the right. Whenever it is tails, you go to the left.

Intuition tells you that on any long walk it is likely that you will be to the left of the center line about as often as to the right; in other words, there will be a lot of “switching sides” (i.e., crossing the center line).

But this is not the case. No matter how long the walk, the most likely situation is that you never switch sides. The second-most likely is that you switch sides only once. The third-most likely is that you switch sides twice, and so on.2

The sum of two even numbers is an even number. The sum of two odd numbers is an even number. The sum of an even number and an odd number is an odd number. Thus, if you select two numbers at random, the odds are 2–1 that the sum will be even. Correct? No, incorrect.

The most common error in probability, an error that can very subtle, is that which considers possibilities as equally probable when they are not. When you select two numbers at random, there are four, not three, equal possibilities (many people incorrectly conflate 2 and 3):

1.even-even = even sum

2.even-odd = odd sum

3.odd-even = odd sum

4.odd-odd = even sum

Thus, it is fifty-fifty; you will get as many odd sums as even.

If you do not believe this, get a random-numbers table. Add the first two digits in each of the first hundred numbers. In the overwhelming majority of the hundred cases, it will be obvious that percentages of even and odd sums are converging on fifty-fifty. However, in a very small percentage of cases, one actually does get even sums approaching or even surpassing two-thirds. This is expected. Those who get this result are urged to sum another two hundred pairs. In nearly every case, these additional sums will make it clear that even and odd sums are converging on fifty-fifty. In such extraordinarily rare cases that it would not be worth mentioning except that we know as surely as we know anything that they will arise in a statistically predictable (tiny) percentage of the cases, there will still be two-thirds of the sums coming up even. If this should happen, do another four hundred numbers. If there is still no convergence on half and half, we will know that the messiah has come (or returned, depending on your point of view) and you are him.

The number of cubes needed to sum to 239 is nine (i.e., 239 = 43 + 43 + 33 + 33 + 33 + 33 + 13 + 13 + 13). No higher number takes more than eight cubes, and it has been conjectured (but not proved) that there is some number after which it never takes more than seven cubes.

A recent test of the mathematical literacy of high school students included a question that was both elegant and interesting.

Let us say that a person is not taxed on the first $10,000 of income, but is taxed 6 percent on all income above $10,000. How much would one have to make for the tax to be 6 percent of the entire income?

The answer is that no matter how large the income over $10,000, if it is taxed at 6 percent, the omitted $10,000 will always make the tax rate on the total income less than 6 percent.

1.The formula for determining that there are thirty-five possibilities is CrN = N! /R!(N - R)! (i.e., # combinations = (7 × 6 × 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1)/(4 × 3 × 2 × 1)(3 × 2) = 35

The formula does not, of course, tell you what the thirty-five sequences are; that must be done by rote.

2.Martin Gardner, Mathematical Circus.