Thousands of years ago, mathematicians wondered whether there is a greatest prime number after which no other number is prime. As mentioned previously, it turns out that there is no largest prime. No matter how large a prime you specify, there is always a larger prime. Later, we shall see the stunningly elegant and simple proof of this.

In Chapter 2 we introduced the idea that in mathematics, “simple” does not mean “easy to do” but rather “relatively few steps from question to answer.” A simple mathematical proof may go undiscovered for millennia and be discoverable only by the greatest of geniuses. This proof did not go through all the possibilities, which is obviously impossible. Nor did it try a lot of possibilities and figure, “Hey, if we haven’t found one by now, there must be none.” Such inductive reasoning, the method that has made science so successful, is not permitted in mathematics. Mathematics requires proof that something is true, or could not be true, of numbers unimaginably large. There is no “very probably” in mathematics.

For a bit of the feel of what a proof is, consider this question: can two consecutive whole numbers both be even? Even without working through the proof, you know that the answer is no. If one number is even, the next will be odd. You do not have to try the impossible task of checking all the numbers. You do not even have to check out every number from 1 to 100. You simply have to point out that when a number is even, the next number will, when divided by 2, leave a remainder of 1. A number divided by 2 that leaves a remainder of 1 is not even. Therefore, there cannot be two consecutive whole numbers that are both even.

You might be thinking, “Yeah, but ‘even’ is practically defined as meaning two consecutive integers cannot both be even.” That is true, but, as we shall see, it is true of all mathematics. The difference is not that it is true of some proofs and not others. It must be true for proof to be possible. The difference between two proofs is that one is obvious and the other is only obvious to a great mathematician.

A mathematical truth differs from a scientific truth in another crucial way. A scientific truth—a fact about the real world—is always tentative. If Mount Everest floats away tomorrow for seemingly no reason, we would not say that, because such an event is seen as impossible by our theories of gravity, Mount Everest could not have really floated away. We would go back to the drawing board and attempt to develop a theory that succeeds in every way the old theory did and also explains why Mount Everest floated away. Likewise, while we are pretty sure that we will never discover a Brazilian tribe of people with two heads, our confidence is based only on probability (an extremely high probability).

Between two randomly chosen consecutive squares, say, four and nine, no one has ever failed to find at least one prime (in this case, five and seven). Are there any consecutive squares that fit within the gap between consecutive primes (i.e., that have no prime in their span)? No one has found such a pair of consecutive squares or proved that there could not be one.

Similarly, between any integer and its double (other than one) there is a prime. This was proved by math genius Paul Erdös at age twenty.

* * *

Is there a solution to this equation (no zeros permitted)?

(x + y + z)3 = xyz

You guessed it. No one knows.

The above two entries are based on Tomorrow’s Math: Unsolved Problems for the Amateur by C. Stanley Ogilvy.

I guess by now you are ready to tackle a problem no one has solved, and you have half an hour to kill before Law and Order. So try this.

A transcendental number is a type of number whose nature was discovered after the types of numbers mentioned in the introduction. It is a number, like e, that is not a solution to an algebraic equation with integer coefficients.

Most numbers—though not those you and I are familiar with—are transcendental. Deciding whether a specific number is transcendental is difficult beyond belief.

Posted on August 4, 2011 by Deskarati

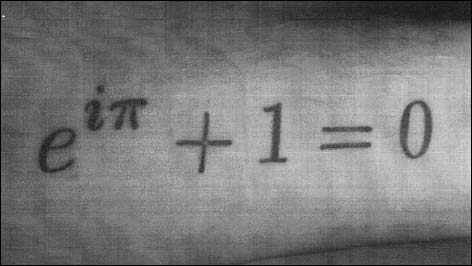

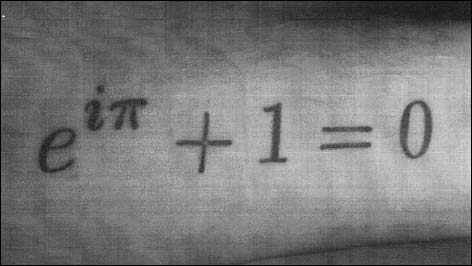

This formula by Leonhard Euler, known as Euler’s identity, was called “the most remarkable formula in mathematics” by theoretical physicist Richard Feynman, for its single uses of the notions of addition, multiplication, exponentiation, and equality, and the single uses of the important constants 0, 1, e, i and π. In 1988, readers of the Mathematical Intelligencer voted it “the Most Beautiful Mathematical Formula Ever”. In total, Euler was responsible for three of the top five formulae in that poll.

Pi is, among other things, the ratio of the circumference of a circle to the circle’s diameter.

The e is, among other things, the base of the natural logarithms.

The basic “imaginary” number i is the square root of −1.

The 0 is the godhead of all numbers.

Euler showed that the relationship among these is:

eiπ + 1 = 0

Many a mathematician claims to have seen the face of God in this equation.

The sum of the sequence of odd numbers always equals the square of the number of numbers.

1 (1 number) = 1sq

1 + 3 (2 numbers) = 2sq

1 + 3 + 5 (3 numbers) = 3sq

1 + 3 + 5 + 7 (4 numbers) = 4sq

1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 (5 numbers) = 5sq

1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 + 11 (6 numbers) = 6sq

1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 + 11 + 13 (7 numbers) = 7sq

1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 + 11 + 13 + 15 (8 numbers) = 8sq

Why?

Consider the middle number of each sequence. In the case of 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 + 11 + 13, the middle number is 7. In the case of a sequence with an even number of numbers, the middle number is the average of the two middle numbers; that is, the middle number of 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 + 11 is 5 plus 7, all divided by 2, or 6.

Note that in each sequence the number of numbers times the middle number equals the sum of the numbers. For example, in 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 + 11 + 13 the middle number (7) times the number of numbers (7) equals 49, or 72. The next sequence is 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 + 11 + 13 + 15. Here the number of numbers (8) times the middle number (8) equals 64. Every increase to the next odd number works in the same way.

It is obvious that a positive times a positive is a positive; negatives never enter the picture. And it is easy enough to see why a positive times a negative is negative (or vice versa); ten times minus (i.e., a debt of) a hundred dollars is minus a thousand dollars, and a hundred times minus ten dollars is minus a thousand dollars.

Nearly everyone knows that a negative times a negative is positive, but most people take this on authority and never quite understand why. In his book The Art of Mathematics, Jerry P. King gives a beautiful explanation.

Consider the number x. Assume that we have proven that there exists an x that can be defined as follows and so define it:

(That is, each solution equals x, so solutions equal each other.)

And: x = (-a)(-b)

Therefore: ab = (-a)(-b)

Which is the same as: (-a)(-b) = ab

Or: (in other words) a minus times a minus is a plus.

In 1993, the IBM Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York ran 566 processors—each effectively a computer—for a year in a test of the theory of quantum chromodynamics, the heart of our understanding of particle interaction. The computers performed over a hundred million billion calculations. The theory passed the test.

In Roman times, the subtractive method of writing numbers was rarely used; 4 was IIII, not IV, and 9 was VIIII, not IX. The subtractive method was not common until the late Middle Ages.

Both methods can be seen on a present-day clock that uses Roman numerals: 4 is usually written IIII, but 9 is never written VIIII.

Euclid

Old Euclid drew a circle

On a sand-beach long ago.

He bounded and enclosed it

With angles thus and so.

His set of solemn greybeards

Nodded and argued much

Of arc and of circumference,

Diameters and such.

A silent child stood by them

From morning until noon

Because they drew such charming

Round pictures of the moon.

—Vachel Lindsay