B REATHING

“It’s not hocus pocus, it’s physiology.”

—Wim Hof

W e started the chapter on cold with the assumption that you prefer temperatures of around 20-21°C (68-70°F). We explained how cold can have a positive effect on your mood and your health. There is a good chance that you have become accustomed to breathing in a certain way—and that can be improved, too.

Many people breathe 13, 15, 17, 20 or as many as 22 or more times a minute. Even when they are sitting quietly in a chair, reading a book. A resting respiratory rate of between six and ten times a minute is enough. Is it bad if you breathe faster than that? Yes, it can be—and we explain why below.

Breathing exercises are considered to have many benefits. They can:

- Help you relax

- Give you more energy

- Help you sleep better

- Help relieve headaches

- Are good for extreme athletes

- Help relieve back and neck problems

- Help relieve intestinal problems

Before we tell you more about the physiology of breathing, first take a look at how you are breathing right now.

DO-IT-YOURSELF:

CHECK YOUR OWN RESPIRATORY RATE

Count how often you breathe in a minute. Each breath begins as you start to breathe in and ends when you stop exhaling, just before you inhale again. Count how often you breathe in 60 seconds and you will know your respiratory rate at this moment.

Just by counting your breaths, you will probably start breathing differently, simply because you are paying attention. So it won’t be a completely accurate picture of how you were breathing before you started to count, but it will give you an idea.

If you breathe more than ten times a minute, then your body is ready for action, but your respiratory rate is not compatible with sitting quietly. Imagine sitting on a chair while you are breathing about 18 times a minute—you would be breathing as though you are running through the park. Of course, you can’t keep that up all day—never mind weeks on end. People suffering from fatigue often look at the cyclists in the Tour de France in admiration and amazement. It’s tough to cycle more than 150 km (93.2 miles) every day for three weeks. Yet, people who feel tired and have a high respiratory rate are working nearly as hard. When a competitive cyclist rests, he breathes only six times a minute and has a heart rate of less than 40 beats per minute. People who are tired breathe too quickly all day and mostly have a resting heart rate of 70 beats per minute or higher.

If a rapid respiratory rate becomes normal for you, you will start to develop health problems.

I have described the benefits of calm breathing earlier in, Verademing , a book I wrote with psychiatrist Bram Bakker. In that book, we showed how irregular breathing leads to health problems. Irregular breathing is either breathing too fast or deeper than necessary.

There is growing interest in correct breathing. More and more doctors and psychologists recommend practicing breath work to relax. Yoga, meditation and mindfulness are becoming increasingly popular. There is growing scientific evidence of the benefits of breathing exercises and meditation. Science is building a bridge between ancient meditation techniques and the much younger Western medicine.

B REATHING T ECHNIQUES: B UTEYKO AND V AN DER P OEL

There are many techniques for breathing besides meditation. The methods of Konstantin Buteyko and Stans van der Poel are very popular in the Netherlands. Buteyko (1923-2003) was a Ukrainian doctor who studied medicine in Moscow. He discovered the effect of breathing exercises on health on October 7, 1952. He had to diagnose a patient who was breathing heavily and who sometimes gasped for breath. Buteyko thought he was dealing with an anxious asthma patient. To his surprise, there were no signs of asthma, but the patient had high blood pressure.

Because Buteyko also suffered from high blood pressure, he started thinking. He observed that he also breathed deeply and heavily. So, he went to his surgery and tried to make his breathing as calm as possible. To his surprise, he noticed that his blood pressure decreased, and his headache faded away.

Buteyko started looking for other links between breathing and health problems. With a lot of practice, he even managed to get his blood pressure back to a normal range without medication. He used this experience to start helping his patients to breathe more calmly and less deeply. He noticed that asthma patients could stop attacks by continuing to breathe calmly.

At the end of the 1950s, Buteyko had his own laboratory fitted out with modern equipment, and he was put in charge of a team of medical specialists. The time was ripe to study the link between breathing and a wide variety of chemical processes in the body and several diseases from a scientific perspective. Buteyko’s research showed that deep, fast breathing can cause a variety of health problems, including high blood pressure, asthma, allergies, panic attacks, chronic bronchitis, hay fever, sleeping problems and headaches.

This knowledge was slow to filter through into regular medicine. For many years, former pulmonary function laboratory assistant Stans van der Poel (1955) worked to give breathing and breathing exercises a more prominent place in health care. If you breathe more calmly, your heart rate will slow down and you will improve the ratio of oxygen to carbon dioxide in your blood. Van der Poel developed equipment to measure breathing, respiratory rate, heart rate and heart rate variability. The advantage of this equipment is that you can measure whether specific breathing exercises work or not.

Van der Poel discovered—in addition to Buteyko’s diagnoses—that people with chronic fatigue, burnout, fibromyalgia and myalgic encephalomyelitis also breathe more rapidly or deeply than is necessary. Patients who could observe the measurements of their decreased heart rate were motivated to start doing the exercises. Besides the exercises, van der Poel urged people to take up a sport. During fitness activities, breath rate is an important indicator of whether people are overexerting themselves. During a stress test, breathing can also indicate the optimal heart rate for energetic recovery. That is very important to know, especially for people who suffer from fatigue.

Our knowledge of breathing can be used and repurposed in various ways. Because of yoga, meditation, Russian doctors, and a Dutch pulmonary function lab assistant, we now have equipment and a number of apps to help us. Western doctors and ordinary people are now recommending and practicing the exercises, with Wim Hof leading the way.

So why are breathing exercises becoming so popular? To find out, we will first take a look at the physiology of breathing.

O XYGEN AND C ARBON D IOXIDE

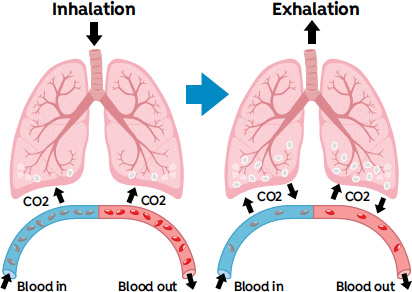

A quick recap: You breathe oxygen in and carbon dioxide out. Oxygen is transferred to your bloodstream by your lungs and carried around your whole body. Excess carbon dioxide is transported in the opposite direction. The lungs have a hierarchical structure and consist of two parts: the left lung and the right lung.

Oxygen enters the lungs through the windpipe (trachea). It passes through the main bronchus into smaller branches known as bronchioles. The bronchioles come out in the alveoli, the air sacs in the lungs where the oxygen comes into contact with the blood. During this “gas exchange”, the ratio of oxygen to carbon dioxide in the lungs and in the blood is the same because of the law of “communicating vessels”. The ideal ratio of oxygen to carbon dioxide in the blood is 3:2.

Oxygen is important for releasing energy from nutrients, while carbon dioxide is important for keeping the blood vessels open. Carbon dioxide is often incorrectly seen as waste—something that must be expelled from the body. But, it is essential that your blood vessels stay open so that oxygen can reach everywhere in your body.

Gas exchange in the lungs

Breathing is not only directly connected to the oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in your blood, but also to your heart rate. Your heart and lungs are inextricably linked to each other. If you breathe faster, your heart rate will almost certainly increase. If you breathe differently, your heart rate changes, as does your heart rate variability. Heart rate variability or heart rate coherence is the variation in time between two successive heartbeats. Someone with a resting heart rate of 60 beats per minute may have a pause of about a second between each beat. But, it is also possible to have intervals between a half and one-and-a-half seconds between beats. The second case is much better than the first.

Contrary to what most people think, it is important for the intervals between heart beats to vary. A healthy heart will beat faster at rest during inhalation than exhalation. In his bestseller, Healing Without Freud or Prozac , French psychiatrist David Servan-Schreiber writes extensively on the importance of good heart rate variability. He claims that people suffering from depression, stress, cancer, or who are in the final stages of life have low heart rate variability without exception. Servan-Schreiber backs up these bold claims with a whole series of scientific studies. He also explores the link between heart rate variability and the autonomic nervous system.

In Healing Without Freud or Prozac , Servan-Schreiber describes how he no longer helps people with anxiety disorders and depression solely with medication, but also gives them exercises to help improve their heart rate variability. He calls this “complementary treatment”. He writes:

“We can witness this interplay between the emotional brain and the heart in the constant variability of the normal heart rate. Because the two branches of the autonomic nervous system are always in equilibrium, they are continually in the process of speeding up and slowing down the heart. That change is why the interval between two successive heartbeats is never identical. This heart rate variability is perfectly healthy; in fact it’s a sign of the proper functioning of the brake and the accelerator, and thus of our overall physiological system.”

H EART R ATE V ARIABILITY, THE N ERVOUS S YSTEM AND B REATHING

The “brake” and “accelerator” mentioned in the previous quote are also known as the parasympathetic and the sympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic nervous system is associated with everything to do with action. If it dominates, your body will be in “fight-or-flight” mode. You will breathe faster, your digestive system will stop working momentarily, and your blood will move from your skin to your muscles, internal organs, and your brain. That is why the sympathetic system is often compared to a car’s accelerator.

The parasympathetic nervous system regulates everything relating to recovery: a slow heart rate and breathing, a good flow of blood to the skin, and an active digestive system. Therefore, the parasympathetic system is sometimes known as the body’s brake pedal.

In their 1989(!) book on the relationship of the parasympathetic nervous system to stress and mental and physical illness, Pieter Langendijk and Agnes van Enkhuizen described the influence of the parasympathetic nervous system on our health. The book also contains concise research data gathered for the Dutch research institute TNO by Professor Tony Gaillard. The results show a direct correlation between decreased activity of the parasympathetic nervous system and physical health problems. It is also clear that breathing exercises can activate your parasympathetic system. (For the record, sex is also primarily a parasympathetic activity).

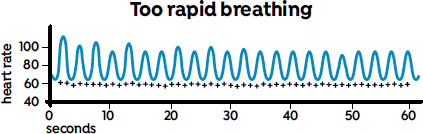

The graphs on the next page show how breathing influences your heart rate variability.

The wavy line is your breathing; it goes up when you breathe in and down when you breathe out. Each time the line goes up then down again is one breathing cycle. The plus signs show heart rate. The vertical axis indicates heartbeats per minute and the horizontal axis is time in seconds. This graph shows the breathing of a 42-year-old woman, sitting on a chair for one minute. Her respiratory rate is 22 and her average heart rate is 61 bpm. Her heart rate is nice and low, but her respiratory rate is high, showing that she is not calm. To further illustrate that, see the graph below which shows her results after practicing breathing exercises for a one minute.

Her respiratory rate is automatically much lower, since she is now concentrating on her breathing. She now breathes only seven times a minute, rather than twenty-two times. Her respiratory rate falls sharply, and her heart has also responded to the exercise: her average heart rate is a little higher at 62 bpm, but the heart rate variability is noticeably better. As these graphs clearly show, if you have a good breathing pattern, your heart rate varies along with the pattern.

Focused breathing exercises are a very good way to improve your heart rate variability. If you have a clear picture of your heart rate variability, you can determine which breathing exercises work well for you. Stans van der Poel’s Co2ntrol , for example, can be very effective, but is very expensive for private individuals. You can still do a lot on your own by concentrating on your heart rate. The cheapest heart rate monitors are a good start. Sit down, put on a heart-rate monitor (if you haven’t got one, you can probably borrow one from a friend who is a keen sportsman or woman) and check your heart rate after two minutes. Do the breathing exercises described in this chapter and see what happens. If your heart rate varies with your breathing, then everything is OK.

B REATHING AND H EALTH P ROBLEMS

Breathing incorrectly can cause a whole range of health problems. We will explain five of them:

- Pain in the shoulders or neck

- Agitation

- Intestinal problems

- Tiring quickly

- Heart palpitations

These problems are all related to breathing in different ways.

1. PAIN IN THE SHOULDERS OR NECK

We have accessory respiratory muscles in our necks that help us breathe faster for short periods. If you continually breathe more rapidly than necessary, these muscles will become overtaxed and start to hurt. The pain is similar to the feeling in your leg muscles after running for a long distance. If you rest, the pain in your legs goes away, and the same applies to the muscles in your shoulders or neck. If you breathe more calmly, the pain will disappear.

2. AGITATION

You feel agitated because breathing too quickly will disrupt your body’s hormone management. You will produce too much adrenaline and that will make you feel agitated and restless.

3. INTESTINAL PROBLEMS

If the balance between oxygen and carbon dioxide in your blood is disrupted, it will have a strong effect on your intestines. Many people with incorrect breathing patterns feel bloated, belch frequently or suffer from flatulence. These problems can be very inconvenient, even though they are not serious.

4. TIRING QUICKLY

Breathing too fast can make you physically exhausted because you are continually using your high-energy glucose reserves. Roughly speaking, the body has two sources of fuel: fats and glucose. If you breathe too fast, your body uses its glucose reserves more quickly than necessary. We have fewer reserves of glucose than of low-energy fats. Burning up your body’s fuel incorrectly in this way means that you will crave sugar and sweet foods more often.

5. HEART PALPITATIONS

Excessive expulsion of carbon dioxide makes your blood vessels contract—the same blood vessels that expand again after exposure to the cold. Your heart tries to compensate for this by pumping blood through your body as quickly as possible. That is a smart response by your body, but it makes a lot of people anxious or short of breath and they often get palpitations.

B REATHING AND S ERIOUS S TRESS-R ELATED D ISORDERS

Besides these five common health problems, psychiatrist Bram Bakker also establishes a link between a high respiratory rate and certain psychiatric disorders. The more serious a psychiatric problem is, the more difficult it is to imagine breathing exercises could offer a solution. Yet, it is still worth considering breathing exercises when addressing serious psychiatric disorders.

Breathing too fast is a sign of stress—and, in the case of any stress-related psychological problem, the patient may have a high respiratory rate. Although stress is a factor in most psychological problems, in practice it is primarily and most commonly linked with anxiety disorders and depression. Rapid breathing also plays a significant role in many as yet unexplained physical complaints that affect more and more people.

Stress only appears explicitly in two diagnoses: acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Both disorders can only be diagnosed as such if the patient has had a traumatic experience. This means by definition, unexpected and radical events that could have resulted in serious injury or even death. Such events can lead to stress and psychological problems and can affect the breathing in the short term or more permanently.

Besides these two stress-related disorders, other anxiety disorders are accompanied by agitated breathing. The most common of these is panic disorder, previously known as hyperventilation syndrome. This diagnosis is no longer used since there is no direct causal link between hyperventilation and panic attacks. In other words, hyperventilation does not always lead to anxiety attacks, and people suffering from panic attacks do not always hyperventilate. An important point in this discussion is to consider how hyperventilation may be defined. In very clear-cut cases, it makes no difference. For example, what is the significance of a slightly higher respiratory rate in a situation where someone is sitting on the couch at home while breathing twice as rapidly as necessary?

As far as we know, this has not been studied, but we suspect that many people who suffer from an anxiety disorder have an excessively high respiratory rate at rest.

Breathing and relaxation exercises have been widely researched and have been found to be effective for anxiety disorders. Yet, they are hardly used by psychologists and psychiatrists. “Applied relaxation” is in the official guidelines for treating general anxiety disorder, but only if cognitive therapy is not available or cannot be applied for some reason. Cognitive therapy only works for people of average or higher intelligence, while applied relaxation—like the WHM—works for everyone. Applied relaxation can be used to help someone recognize the early signals of panic and gain control through relaxation exercises. First, the patient will learn to relax. Then, relaxation can be associated with a certain word that has a calming effect. When panic signals occur, this word can be used to stop the panic from getting worse.

Our short detour into psychiatry was to emphasize the importance of breathing for treating a wide range of health problems—and to show that there are other exercises besides the WHM breathing exercises that can be used for relaxation.

W HY D O M ANY P EOPLE B REATHE S O R APIDLY?

Why do so many of us breathe incorrectly? Breathing calmly should be as automatic as many of our other bodily functions. Our body temperature is always 36.8°C (98.2°F), our hearts keep on beating, and our eyes blink by themselves. Why don’t we breathe calmly as a matter of course—especially if it is healthier for us? It seems that excessive stimulation, worry, preoccupation, and persistent mental pressure all affect our breathing.

B REATHING AND THE B RAIN

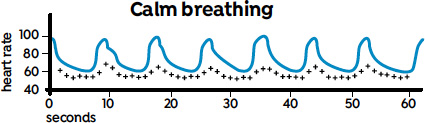

The neocortex is the part of the brain that distinguishes humans from other animals. “Neo” means “new” in Latin and, in evolutionary terms, the neocortex is the youngest part of the brain. We use it to analyze and calculate, and it is also our language center. But, it is also the part of the brain that allows us to worry about what will happen in two weeks’ time—or allows us to stay irritated about a past event.

The “mammalian” or emotional brain is where we process the emotions we share with other mammals, such as fear, aggression, love and sorrow. The limbic system is found in this part of the brain.

A layer deeper is the reptilian brain, where we find the functions we share with reptiles. Our blood pressure, heart rate, and breathing are regulated here. Likewise, the reptilian brain keeps our body temperature at 36.8°C, without our conscious attention.

The neocortex also filters external stimuli. Research has shown that today we are exposed to as many external stimuli in one day as someone living in the Middle Ages encountered during a lifetime. We make an average of 2,800 choices each day—every day. So, it is not surprising that at some point, we will receive too many signals to handle. One way the resulting agitation manifests itself is in more rapid breathing.

An over-stimulated neocortex can make us breathe faster. But you can also use the neocortex to slow down your breathing.

B REATHING E XERCISES TO H ELP Y OU R ELAX

The exercises in my book, Verademing , are mainly focused on relaxation, and restoring a normal balance between oxygen and carbon dioxide in the body.

Here are two breathing exercises that are good for relaxation:

— Breathe in through your nose

— Breathe out through your nose

— Pause

— Breathe in through your nose

— Breathe out through your nose

— Pause

Don’t pause as long as possible, but just until you feel the need to breathe in again.

If this exercise doesn’t relax you, breathe out through your mouth:

— Breathe in through your nose

— Breathe out through your mouth, prolonging the breath a little

— Pause

— Breathe in through your nose

— Breathe out through your mouth, prolonging the breath a little

— Pause

You can easily prolong your breath by holding back so that your cheeks puff out a little as you breathe out. It is good to relax by practicing these breathing exercises for two minutes before you start doing the WHM exercises. The WHM exercises are completely different and serve a different purpose—which will be explained later.

T HE WHM B REATHING E XERCISES

The Wim Hof breathing exercises are not intended to relax you—at least not while you are doing them. They are designed to enable you to control your mind and body, so you can influence your autonomic nervous system.

At first, the WHM exercises will make you light-headed. It is hard work to keep your attention focused while doing the exercises properly.

So far, we have only referred to breathing exercises and not to meditation. Yet, Hof’s exercises have their origins in a Tibetan technique known as Tummo meditation.

Tummo is a form of meditation with its roots in the Indian Vajrayana tradition. Vajrayana is a religion that probably emerged around the fourth century AD, and which was heavily influenced by Tantric and Hindu teaching. Vajrayana works from a cause and effect perspective. The aim is to transform every experience into fearless wisdom, spontaneous joy and energetic love. Hof emphasizes that this does not necessitate or imply faith in a higher power—rather, that what you experience be true for yourself. Followers of Vajrayana see the method as the most important link in achieving enlightenment through the Buddha’s teaching.

T UMMO T ECHNIQUE

Tummo combines breathing with visualization. It involves breathing in deeply and breathing out slowly. While breathing, practitioners visualize flames, as a method to help raise their body temperature. Because they focus on experience and not on faith, they also embrace science. In the scientific journal PLOS ONE , researchers from the National University of Singapore described their study of nuns who practiced Tummo meditation. They discovered that the nuns could generate extra body heat, increasing their temperatures to 38.3°C (100.9°F), in an ambient temperature of -25°C (-13°F). With their bodies, they were also able to dry wet clothes which were wrapped around them.

Wim Hof did not study Tummo directly. He learned everything from nature, not from a religion. However, after his own experience, a knowledge of Tummo helped Wim gain a deeper understanding of the power of cold. And what most appeals to him is the idea that Vajrayana is a religion based on experience, not faith. It is about experiencing, not believing. Every proposition can ultimately be checked against your own experience. One of Wim’s favorite one-liners is: “feeling is understanding”. And that’s exactly what the Tummo techniques encourage.

DO-IT-YOURSELF:

THE WHM BREATHING EXERCISES

A word of warning in advance: Don’t do this breathing exercise in a position or location where fainting might be dangerous, such as in the shower, underwater, while standing up, or in the car. Do it under supervision the first time.

— Breathe in deeply, and then exhale

— Breathe in deeply, and then exhale

— Breathe in deeply, and then exhale

— Breathe at a pace and rhythm that feel most comfortable

— Repeat this 30 times

— The last time, breathe out completely, then in again very deeply, out again slowly, and then wait.

Breathe in deeply, without forcing yourself, and then out again slowly. By not fully breathing out, a small amount of air remains behind in the lungs. After doing that 30 times, hold your breath after breathing out, and wait until you feel the need to breathe in again. Repeat this exercise until you feel tingling, light in the head, or sluggish.

By breathing in deeply and out slowly, you expel a lot of carbon dioxide. The CO2 concentration in your blood will decrease and your blood vessels will contract. When you hold your breath after breathing out, your body retains a large quantity of carbon dioxide, and your body compensates by releasing more oxygen in the mitochondria. Mitochondria supply the energy for your body’s cells. More oxygen in the mitochondria generates more energy. Waste substances are expelled and the oxygen has more room to penetrate deeper into the cell. Holding your breath after exhaling leads to a parasympathetic reaction (in other words, you relax). This leads to aerobic dissimilation in the cell. By breathing more deeply and consciously, we can therefore generate more energy in the cell.

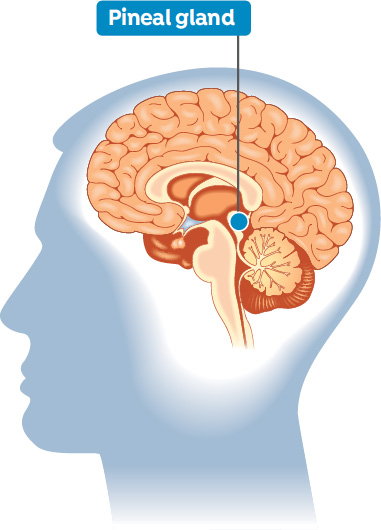

P INEAL G LAND

After these breathing exercises, many people experience an expanded form of consciousness. This is likely from the mitochondrial activity in the brain cells releasing chemicals in the pituitary and pineal glands. The pineal gland (epiphysis cerebri) is very important for determining our state of mind. It produces melatonin, a hormone that plays an important role in our sleep-wake and reproductive rhythms. Our hypothesis is—that through the WHM breathing exercises—much more oxygen enters the pineal gland, so the body will generate a lot more oxygen. That explains why the exercises work so well in combating jetlag, sleeping problems and depression.

Interestingly, in Eastern philosophies, the pineal gland is seen as the seat of the soul. The French philosopher René Descartes (1596-1650) also considered it to be the link between body and soul. He was one of the first Western thinkers to “promote” the pineal gland.

B REATH R ETENTION

You can check whether your body changes during the breathing exercises by measuring how long you can hold your breath. Check how long you can hold your breath before doing the exercises, and then again afterwards. You will notice that you can hold your breath longer and longer.

It is good if your retention time (the time between breathing out and back in again) gets longer, but don’t make a competition out of it. It is a way to determine if the method is working, not an end in itself.

S UMMARY

- Many people breathe quicker or deeper than necessary

- A disrupted breathing pattern is related to a series of health problems

- Breathing exercises affect brain activity

- There are exercises you can use to relax

- The WHM uses breathing to access the pineal gland

- Oxygen activates the expulsion of waste substances

- Carbon dioxide opens the blood vessels