A

Pneumoperitoneum (gas in the peritoneal cavity)

Pneumoperitoneum literally means free gas in the peritoneal cavity. It usually indicates bowel perforation. Free gas may also be seen up to 3 weeks after abdominal surgery and in trauma (e.g. stabbing).

Main causes of pneumoperitoneum:

- Perforated peptic ulcer

- Perforated appendix/bowel diverticulum

- Post-surgery

- Trauma

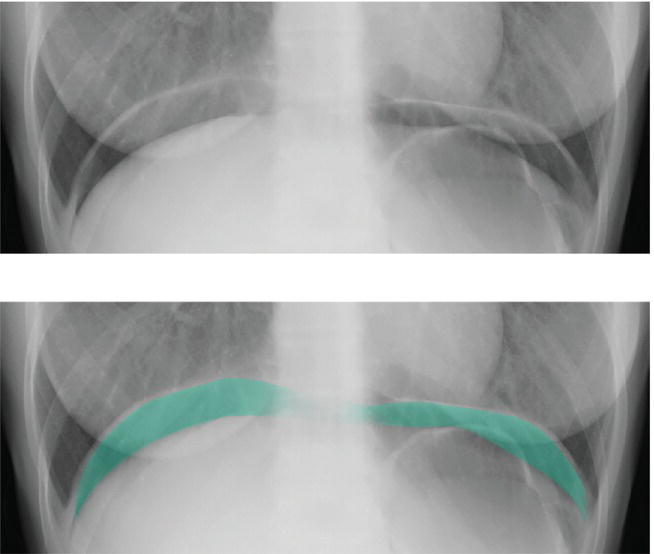

Figure 17: Two identical erect radiographs of the lower chest. The lower radiograph shows the pneumoperitoneum marked in turquoise.

The radiological signs of a pneumoperitoneum are as follows:

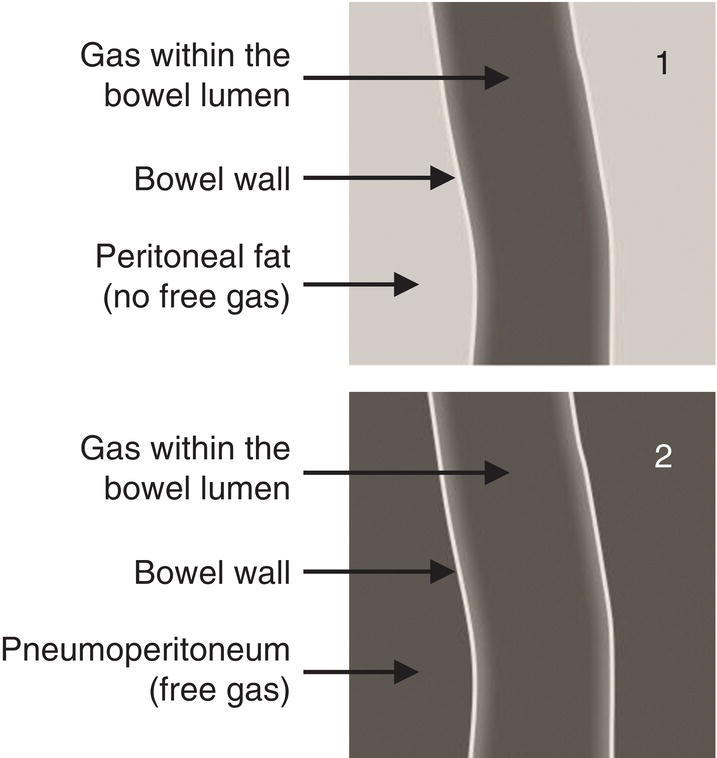

- Rigler’s sign: Also known as the double-wall sign, this is seen when gas is present on both sides of the intestinal wall (i.e. gas within the bowel and free gas in the peritoneal cavity).

Normally the bowel wall is only just visible, outlined by the gas within the bowel and peritoneal fat outside of the bowel. With a pneumoperitoneum the bowel wall is easily seen as it is outlined by gas within the bowel and gas outside of the bowel.

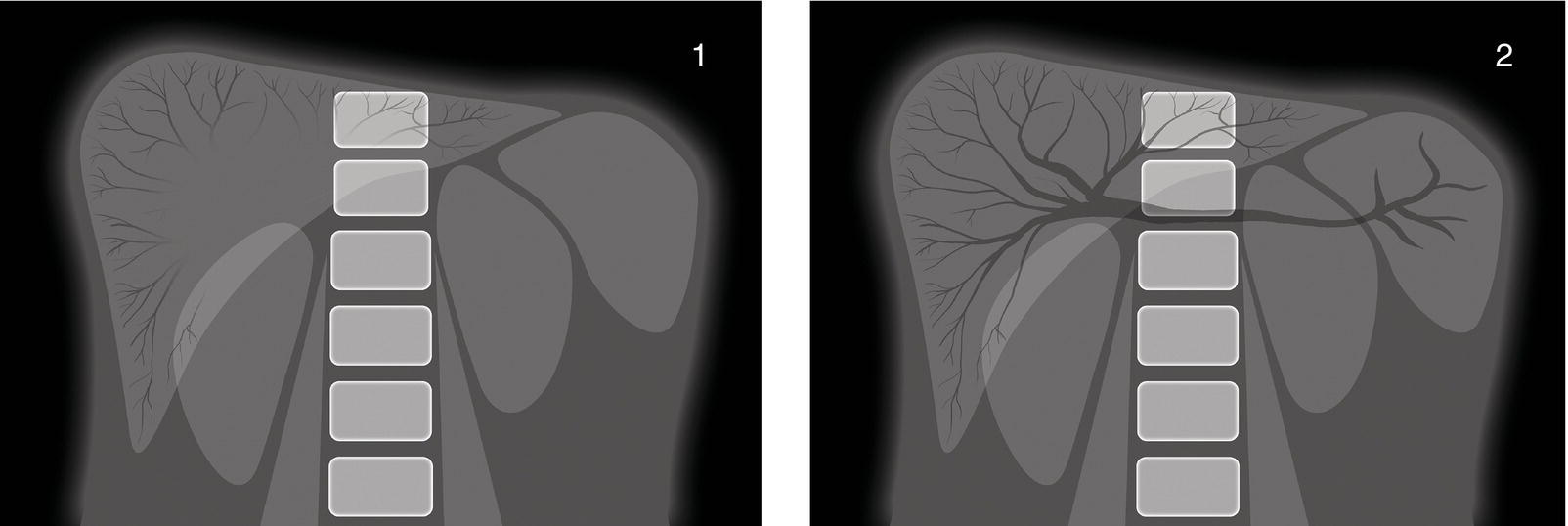

Figure 18: 1. Diagrammatic representation of normal appearances of the bowel wall. The lumen of the bowel contains gas. You can see the bowel wall, but there is little contrast between the bowel wall and the peritoneal fat outside of the bowel. 2. Diagrammatic representation of Rigler’s sign (double-wall sign). The lumen of the bowel contains gas, and there is also gas within the peritoneal cavity. The bowel wall is therefore clearly seen outlined by the gas either side.

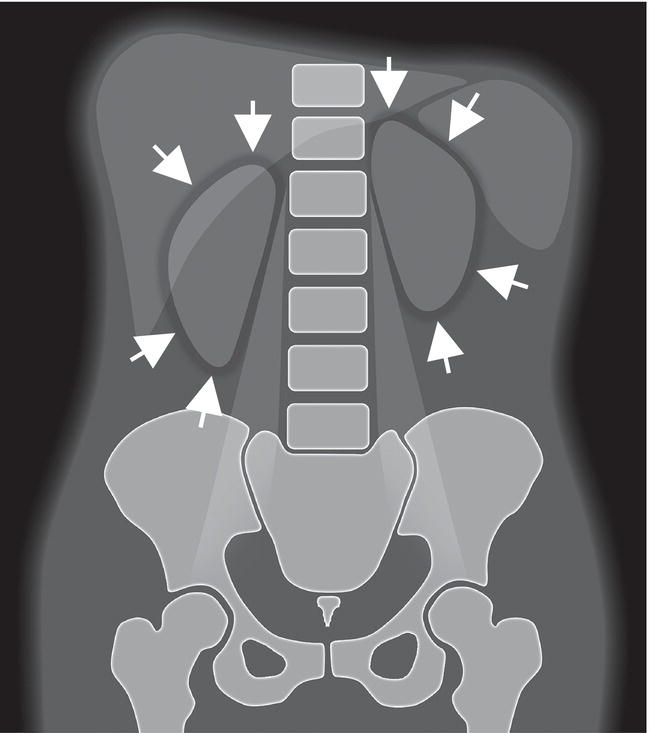

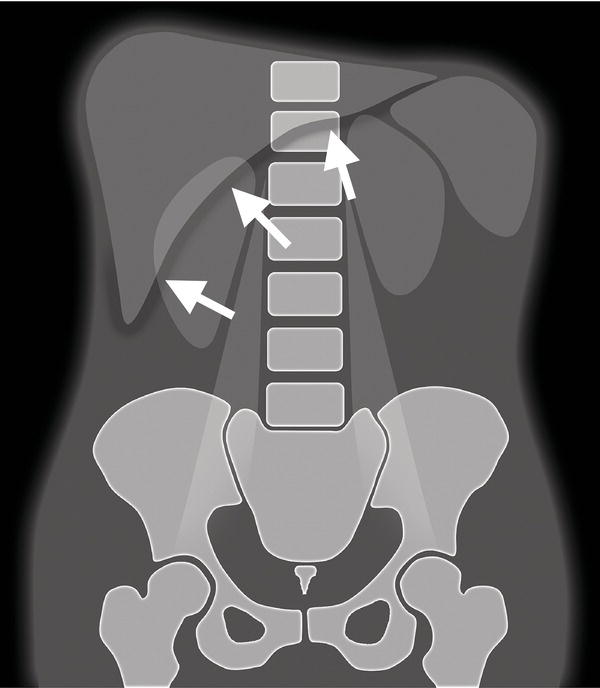

- Gas outlining the liver: The liver edge may become easily visible due to surrounding free intra-peritoneal gas. Normally the liver (light grey) is outlined by peritoneal fat (dark grey). However, if there is a pneumoperitoneum, the liver is outlined by gas (black) giving a much greater contrast and therefore better visualisation of the liver edge.

Figure 20: Diagrammatic representation of gas outlining the liver. When free gas is present in the peritoneal cavity, the liver edge is seen much more easily. The position of the liver edge is shown by the white arrows.

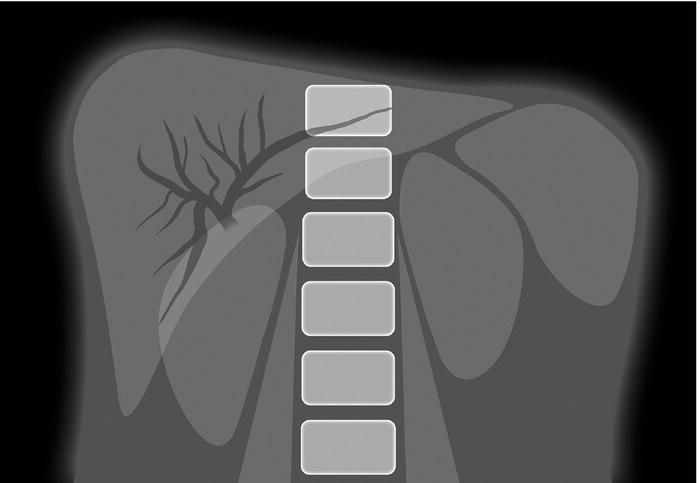

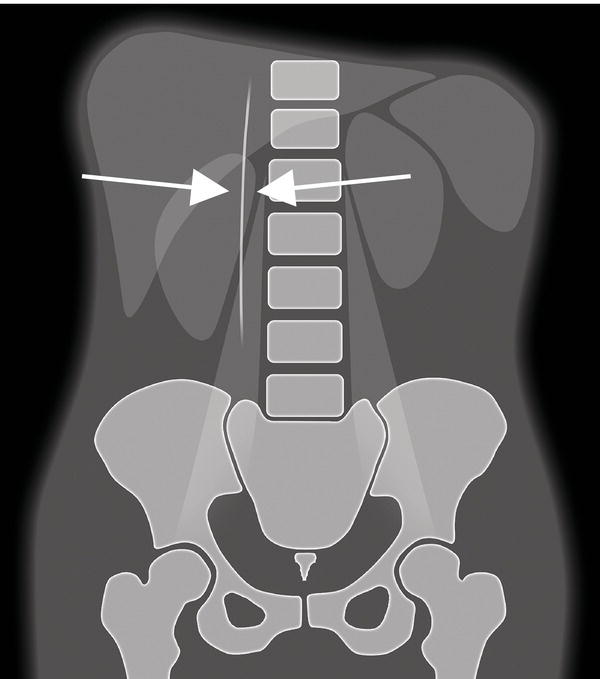

- Falciform ligament sign: The falciform ligament is a ligament attaching the liver to the anterior abdominal wall (a remnant of the umbilical vein). Normally it is not visible; however, the ligament may become visible if outlined by free intra-peritoneal gas either side of it in a supine patient.

Figure 21: Diagrammatic representation of the falciform ligament sign. When free gas is present in the peritoneal cavity and the patient is lying supine, the falciform ligament becomes visible in the right upper quadrant as an opaque line extending inferiorly from the liver. This line appears in the position as shown by the white arrows.

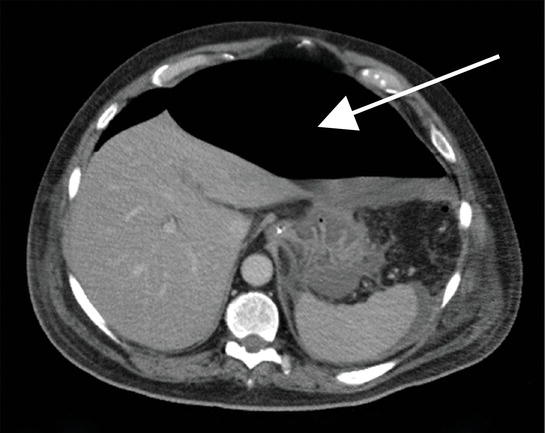

Figure 22: A CT slice through the abdomen showing a pneumoperitoneum. The gas is marked with an arrow.

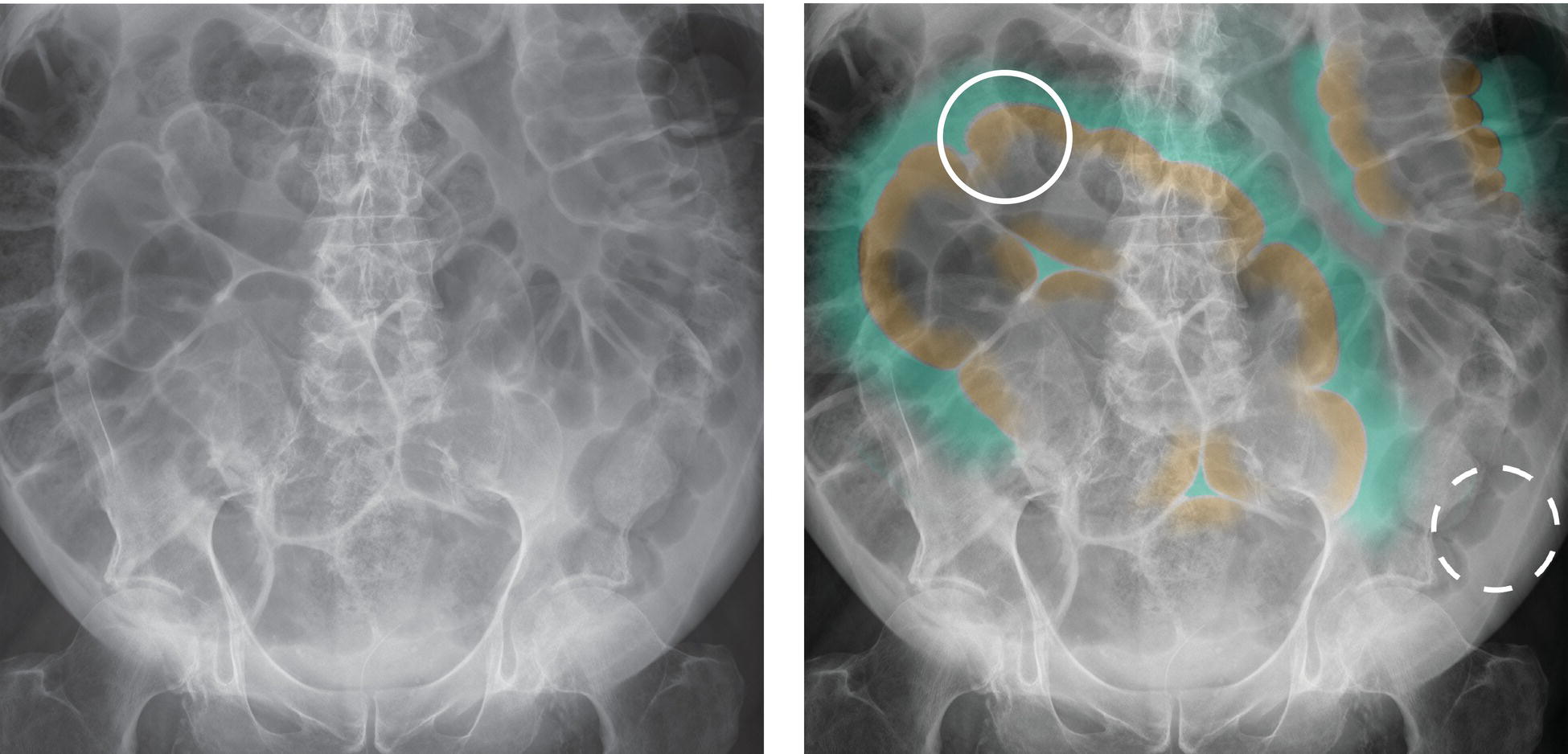

Example 1

Figure 23: Two identical abdominal radiographs showing a pneumoperitoneum. There are loops of bowel with gas outlining both sides of the bowel wall in keeping with Rigler’s sign. The right radiograph shows in turquoise and brown the areas where Rigler’s sign is most clearly seen. The lumen of the bowel is marked in brown and the free gas outlining the bowel wall marked in turquoise. The best example of Rigler’s sign is marked with a white circle. An area of normal appearing bowel wall is marked with a white dashed circle for comparison. (You can also see dilated loops of large bowel.)

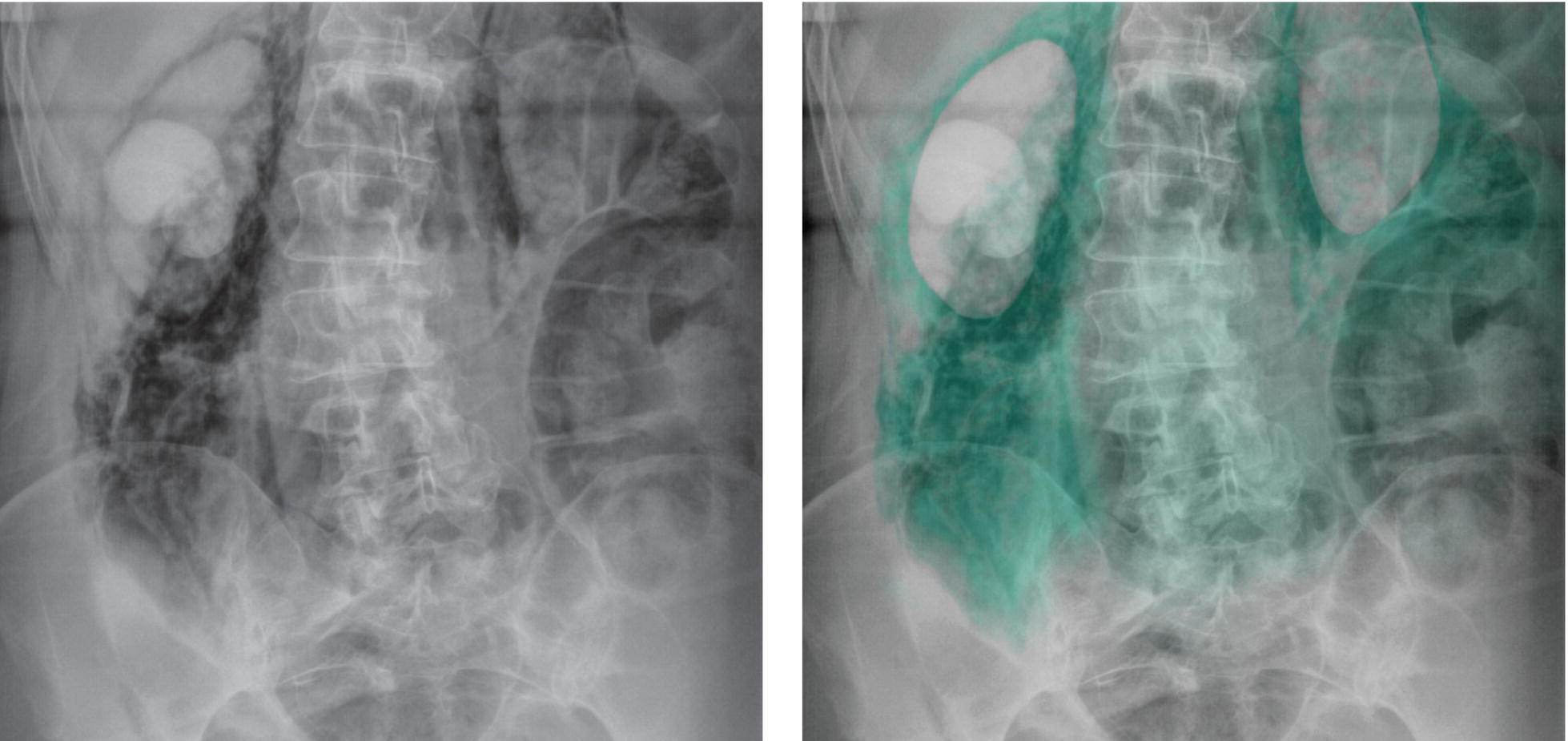

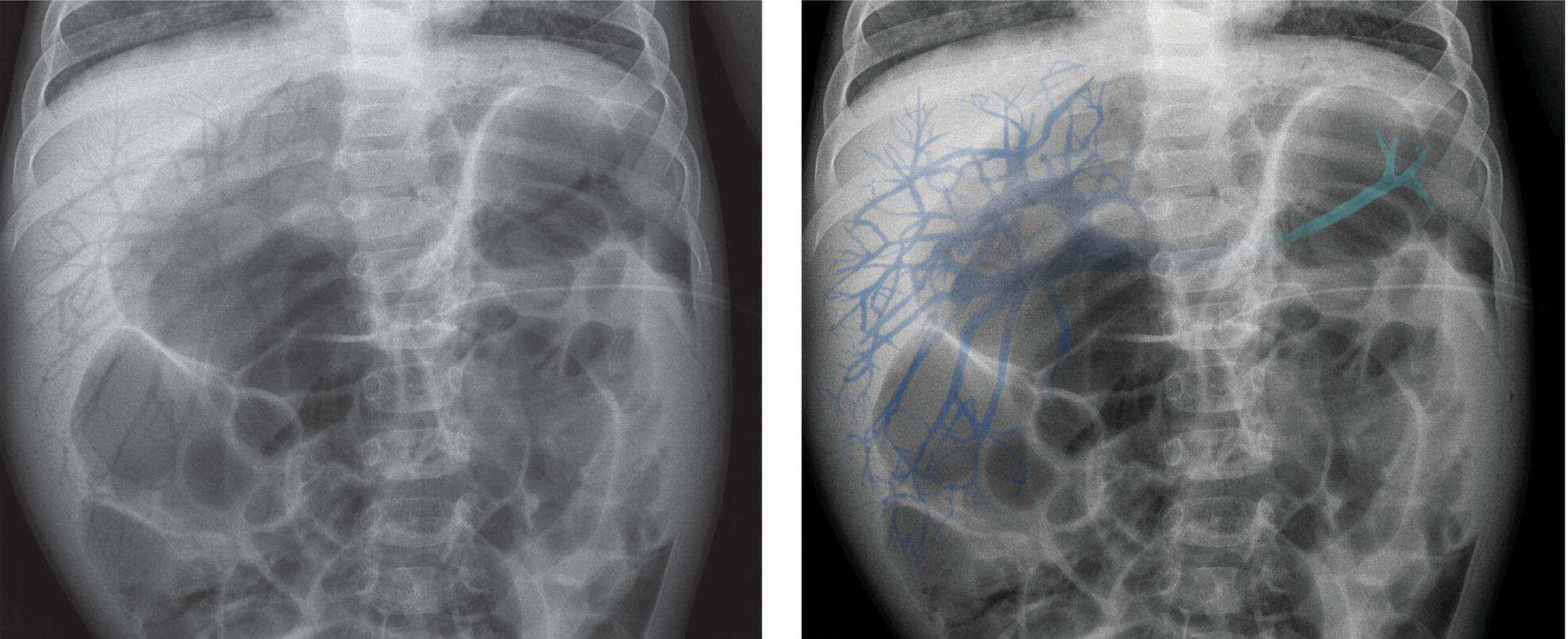

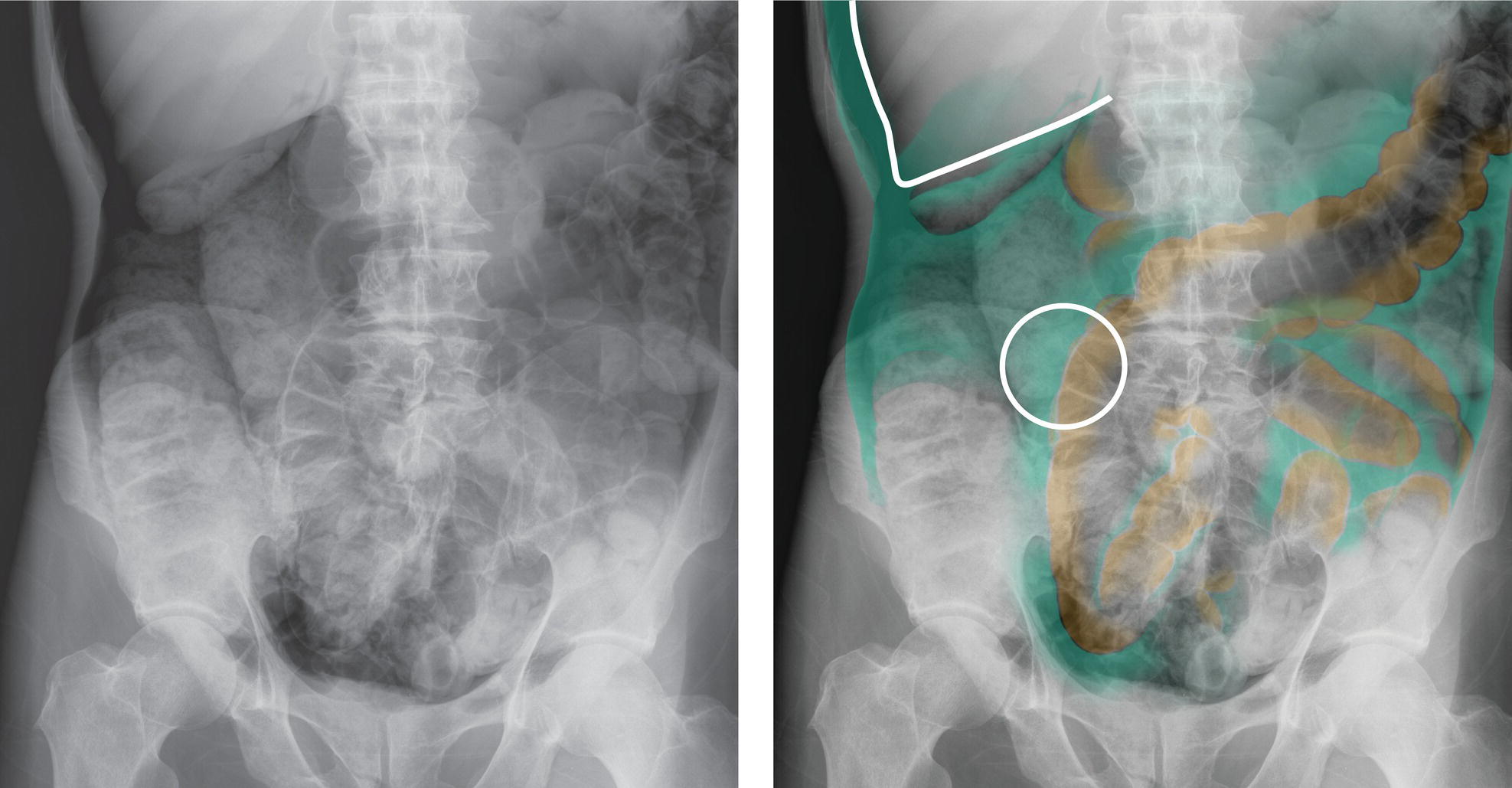

Example 2

Figure 24: Two identical abdominal radiographs showing a large pneumoperitoneum. There are loops of bowel with gas outlining both sides of the bowel wall in keeping with Rigler’s sign. The right radiograph shows in turquoise the areas where the pneumoperitoneum is most clearly seen. Where Rigler’s sign is most clearly seen, the lumen of the bowel is marked in brown. The best example of Rigler’s sign is marked with a white circle. You can also see gas outlining the liver as shown by the white line.

Example 3

Figure 25: Two identical abdominal radiographs showing a pneumoperitoneum. There is a dilated loop of bowel with gas outlining both sides of the bowel wall in keeping with Rigler’s sign. The right radiograph shows in turquoise and brown the areas where Rigler’s sign is most clearly seen. The lumen of the bowel is marked in brown and the free gas outlining the bowel wall marked in turquoise. The best example of Rigler’s sign is marked with a white circle.

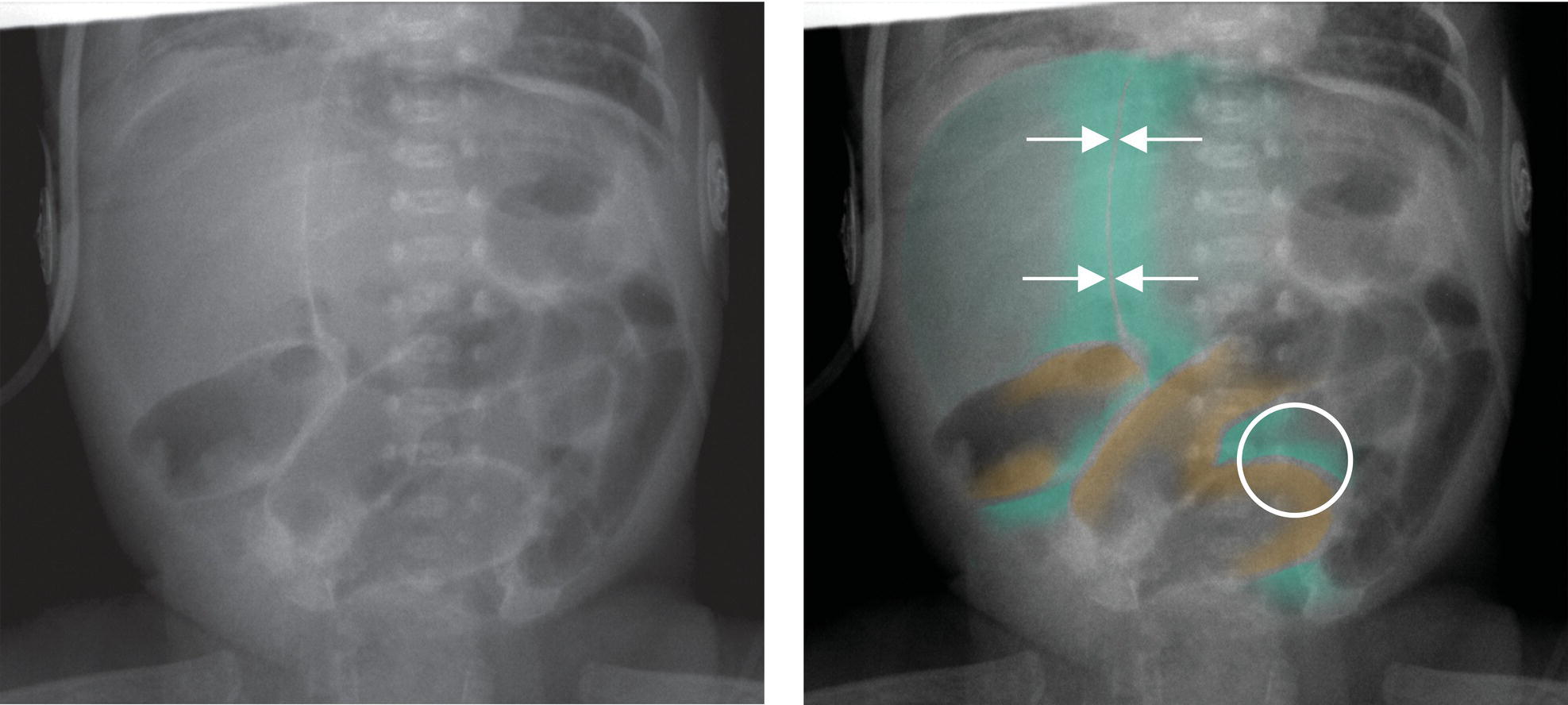

Example 4

Figure 26: Two identical abdominal radiographs of a young child showing a pneumoperitoneum. There are loops of bowel with gas outlining both sides of the bowel wall in keeping with Rigler’s sign, and there is gas outlining the falciform ligament in keeping with the falciform ligament sign. The right radiograph shows in turquoise and brown the areas where Rigler’s sign is most clearly seen. The lumen of the bowel is marked in brown and the free gas outlining the bowel wall marked in turquoise. The position of the falciform ligament is shown with white arrows. The best example of Rigler’s sign is marked with a white circle. (You can also see dilated loops of bowel.)

Example 5

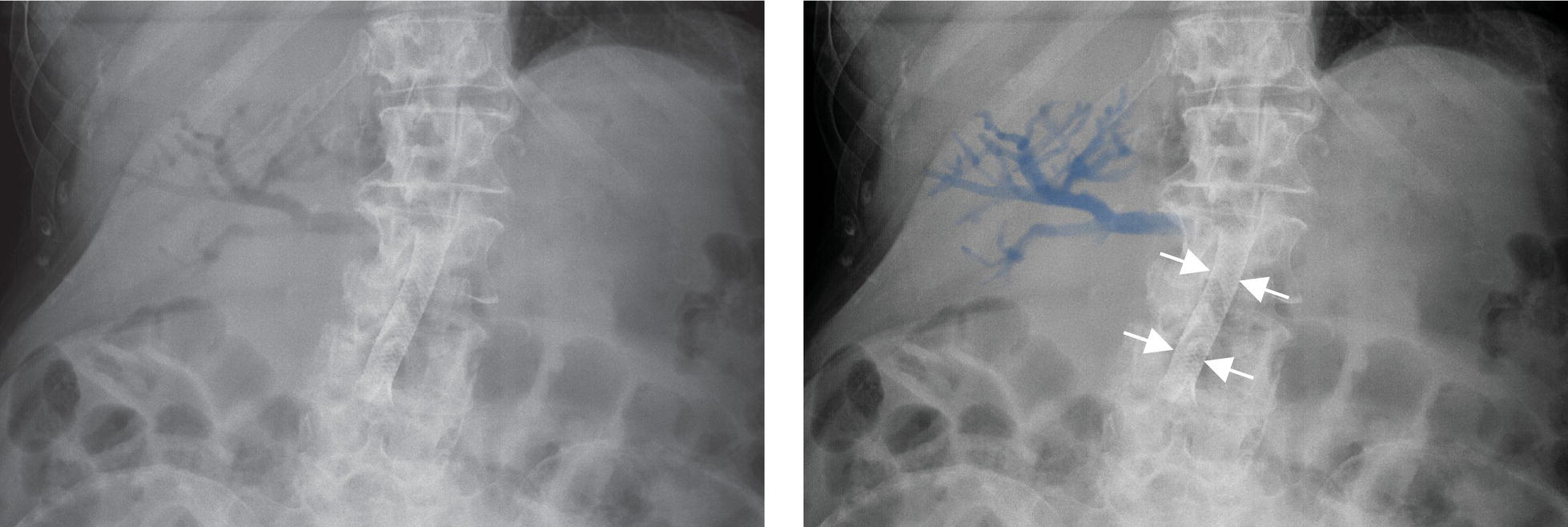

Figure 27: Two identical abdominal radiographs of the upper abdomen showing a pneumoperitoneum. There is gas outlining the falciform ligament in keeping with the falciform ligament sign and there is also gas outlining the liver. The right radiograph shows in turquoise the areas where the pneumoperitoneum is most clearly seen. The position of the falciform ligament is shown with white arrows and the outline of the liver edge is shown by the white lines.

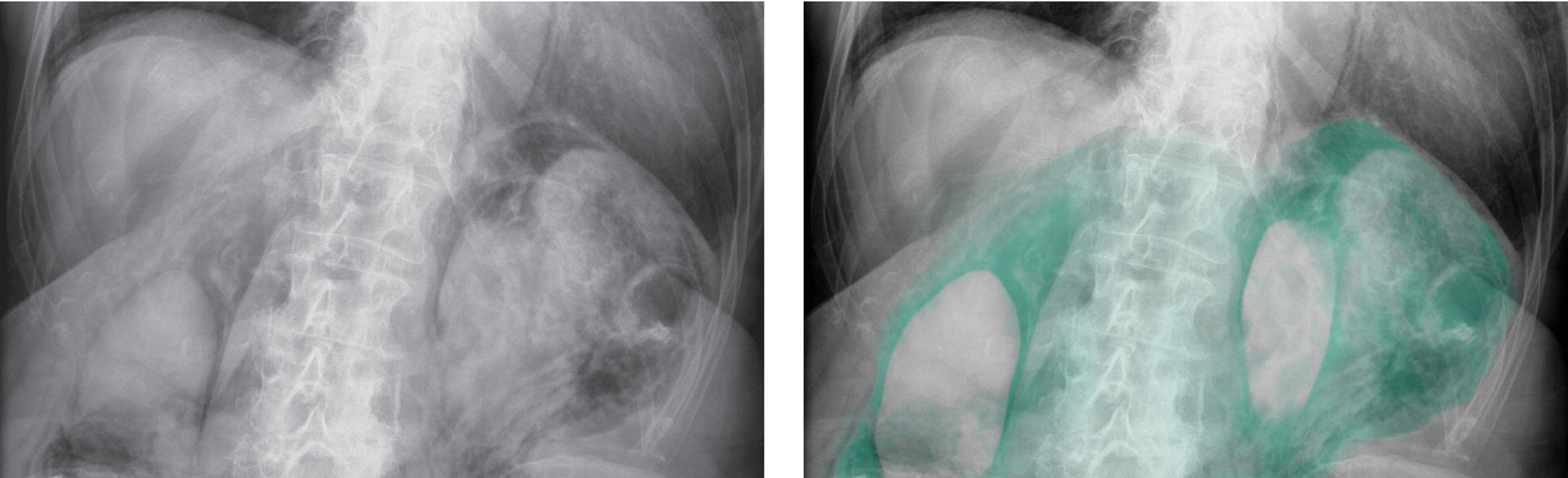

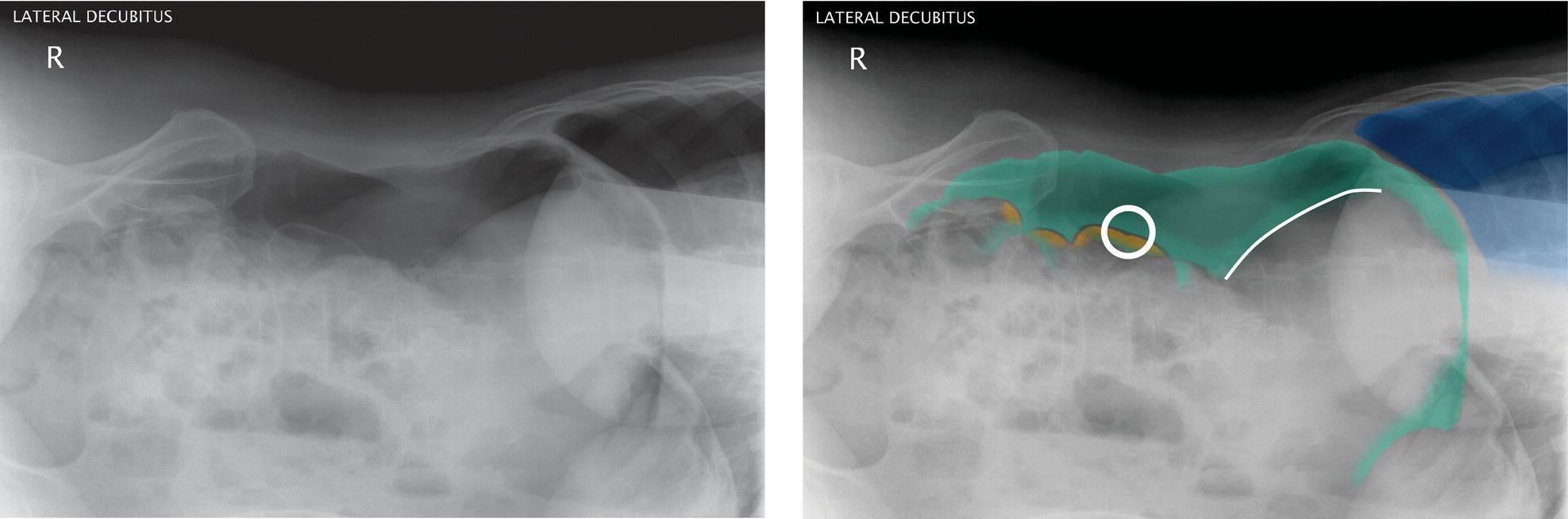

Example 6

Figure 28: Two identical abdominal radiographs taken in the left lateral decubitus position showing a large pneumoperitoneum. The patient is lying on their left side. You can see the bony pelvis on the left of the image, and the dark area on the top right of the image is the base of the patient’s right lung. There are loops of bowel with gas outlining both sides of the bowel wall in keeping with Rigler’s sign and there is also gas outlining the liver. The right radiograph shows in turquoise the areas where the pneumoperitoneum is most clearly seen. Where Rigler’s sign is most clearly seen, the lumen of the bowel is marked in brown. The best example of Rigler’s sign is marked with a white circle. You can also see gas outlining the liver as shown by the white line. The right lung is marked in blue.