Any day Rose expected to receive her “special” fruitcake, in which apples and raisins were replaced by a wad of Confederate bills and a letter detailing her escape route to Richmond. When a guard finally came to her room, holding a cake aloft, he said that he had investigated her original confection with the aid of a penknife and had found it unsuitable: perhaps she would instead accept this version, with all of the usual ingredients? His lips tugged up into a smirk, waiting for her response, for her fury to rise like cream, and she couldn’t stop herself from yielding. She yanked the cake from the platter and hurled it down the stairs, watching it bounce once and split against the wood, listening to the guard laugh behind her.

Two weeks later, on Saturday, January 18, Rose was reading in the library while Little Rose sat at her feet, playing with her dolls. A guard appeared in the doorway and told her that, after five months of house imprisonment, she was being transferred to a military prison on Capitol Hill. She had two hours to pack, including the time it would take to examine each article before it was placed in a bag. To her surprise, she was permitted to bring her pistol but no ammunition, a situation she hoped to remedy from behind bars. Little Rose would be accompanying her, staying in the same cell, and she also hoped that together they could continue spying from the inside.

Pinkerton ordered that the windows of Rose’s house be boarded and all paper removed from the premises. He wanted to transport her in a covered wagon with military escort, but one of her more sympathetic guards, Lieutenant Sheldon, insisted that she ride in a private carriage. “Good-bye, Sir,” Rose said, and paid him the highest compliment she could muster for a Yankee: “I trust that in the future you may have a nobler employment than that of guarding defenseless women.” Little Rose looped her arms around his neck and hugged him.

Rose seized one more opportunity to bedevil her captors, leaving two bottles of synthetic ink, the kind used to encode messages, next to her sewing machine—a way to distract attention from her real means of communication. She took one last look at the framed portrait of Gertrude—her daughter had inherited her “same strange fancy of the eye”—and left her home, she feared, for the very last time.

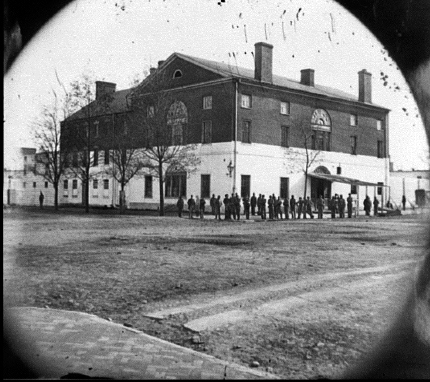

Old Capitol Prison.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The Old Capitol Prison stood on the east side of First Street, a dreary jumble of structures that had temporarily housed Congress when the British burned the unfinished Capitol during the War of 1812. Its heart was a three-story pile of brick dominated by a large arched window, barred with wood latticing to deter escapes. For Rose, the building embodied a piece of personal history. In a previous incarnation it had been Hill’s Boarding House, her aunt’s establishment and her very first home in Washington, the place where she and her sister came to live after their father was killed and their mother could no longer care for them.

She was only three or four years old, living in Montgomery County, Maryland, on a farm called Conclusion, where fifteen slaves planted wheat and tobacco and obeyed her father’s every order. John O’Neale (the final e was dropped from the family name in Rose’s early childhood) was a libertine, with a particular taste for horse racing, cockfighting, and drinking. He often brought his favorite slave to the local tavern. Jacob was his most prized possession, twenty years old and freakishly double jointed, able to execute astounding acrobatic feats for the amusement of John’s friends. One night in April 1817, John and Jacob went out drinking, but only Jacob came home.

Early the next morning Jacob set out to look for his master and saw him on the road, about 150 yards from the house, thrown from his horse and lying on the ground, bleeding from the head. He rushed home and sought help from another slave, who advised him go back and make sure that John was dead—or else he might blame Jacob for his injuries. Jacob allegedly complied, hoisting a rock and crushing his master’s skull. A doctor’s examination discovered three head wounds, one from the rock and two from the fall, but it was impossible to conclude which was the fatal blow. Jacob asserted his innocence, was tried and found guilty, and was hanged six months later. For Rose, her father’s murder became a hazy, shapeless memory, but one that colored every moment of her life.

Rose’s mother, Eliza, found herself a widow at twenty-three, with four daughters and another on the way, and only $2,600 to her name. The price of wheat and tobacco was plummeting and she would soon be forced to sell the farm. In 1828, eleven years after John’s death, she sent her second and third daughters, the “extra” ones, Ellen and Rose, to their aunt’s boardinghouse in Washington, hoping the city would be kind to them.

Behind the walls of this building, as a teenager, Rose lived among Whig and Democratic congressmen from North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee, who stayed there when Congress was in session. Rose and Ellen, two years older, always joined the men for dinner, passing heaping platters of crab cakes and baked perch from the Chesapeake Bay, listening to political gossip, learning the nuances of cronyism and the etiquette of the backroom deal. These conversations, more than her occasional lessons in a classroom, constituted Rose’s true education. When weather permitted, she donned her best bonnet, took a carriage to the Capitol, and watched debates in the Senate chamber, where hickory logs smoked in two rusty stoves and streams of tobacco juice trickled across the floor. She scrutinized the politicians’ body language as closely as their speech, noting how the slightest gesture—a twitch of the jaw, a dip of the brow—could betray doubt or weakness. She delighted in the hidden meanings skimming below the surface of their sentences, the art and power of the unspoken. She grew acutely aware of her own physical idiosyncrasies and quirks, of how her voice sounded inside her own ears, and she practiced controlling its resonance and timbre; no one would ever have cause to misconstrue her words.

The men noticed Rose, too, with her black eyes and sleek skein of hair, her figure that curved like a vase. She had learned enough about politics to compare rumor and truth, and cultivated an air both regal and flirtatious. “She was a celebrated belle and beauty,” one acquaintance said, “the admiration of all who knew her,” and numerous men vied to escort her about town. Tennessee congressman Cave Johnson was an early suitor and, at twenty years her senior, thirty-six to her sixteen, old enough to be the father she’d barely known. He introduced her to his powerful friends, including Pennsylvania congressman James Buchanan, who, nearly thirty years hence, would seek Rose’s advice during his successful presidential campaign. Every night, Rose especially looked forward to sitting in the parlor with South Carolina statesman and future vice president John C. Calhoun, who became her “kindest and best friend.” She was at Calhoun’s bedside when he died in 1850, and now, entering the prison, she recognized the room in which he had drawn his last breath.

A guard led her and Little Rose to the office of Superintendent William P. Wood. He was thirty-six years old and a solid block of a man, seemingly as wide as he was tall. One colleague described him as “short, ugly, and slovenly in his dress; in manner affecting stupidity and humility, but at bottom the craftiest of men.”

Little Rose stepped forward and looked up at him. “You have one of the hardest little rebels here you ever saw,” she said. “But if you get along with me as well as Lieutenant Sheldon”—the one guard both she and her mother liked—“you will have no trouble.”

For once, Rose objected to her daughter’s bravado: “Rose, you must be careful what you say here.”

The Old Capitol Prison had originally been intended only for Confederate prisoners of war but soon housed a motley assortment of inmates. The two northerly buildings were occupied by blockade runners and bounty jumpers—men who enlisted in a regiment, collected the on-the-spot cash bounties given to volunteers, and then deserted, only to magically turn up a few weeks later in a different state, under a different name, to join another regiment. Confederate soldiers captured in battle were confined to the lower floor and basement, and a four-story structure in the middle section held suspected spies.

Rose and her daughter settled into their quarters, a room in the back with a view of the prison yard; Superintendent Wood feared Rose might connect with Southern sympathizers strolling along the sidewalk out front. The space was ten feet by twelve and furnished with a straw bed, soiled cotton sheets, a small feather pillow (“dirty enough,” Rose observed, “to have formed part of the furniture of the Mayflower”), a few wooden chairs, a wooden table, a fireplace, and a cracked mirror. Every breath carried the overwhelming stench of the latrines, located across the prison yard in a wooden building that doubled as the hospital and apothecary.

A carpenter arrived to install bars on the windows. He told Rose that the prison’s commanding general had sketched the drawings himself, placing the bars to block maximum air and sunlight. When Superintendent Wood protested that this measure wasn’t necessary, Andrew Porter, Washington’s provost marshal, scoffed. “Oh Wood,” he said, “she will fool you out of your eyes. She can talk with her fingers.”

The following morning she opened her barred window, hoping for a sip of fresh air.

“Get away from that window!” a guard called from the yard below. He raised his musket and she responded in kind, leveling her unloaded pistol at his head. She’d heard he had orders “not to shoot the damned Secesh woman, who was not afraid of the devil himself,” and kept her aim steady long after he had given up.

The guards knew exactly how to retaliate, Rose had to admit, filling the cells around her with escaped slaves, who streamed into Washington from Virginia and were admitted to the prison as an act of charity. She did not appreciate being taunted by these Negroes, who told her, “Massa Lincoln made me as good as you,” and insisted that they be called “gem’men of color.” Whenever a Negro servant entered to clean Rose’s room, the guards bolted and locked the door. She screamed and rapped her knuckles raw against the iron, begging to be let out.

“The tramping and screaming of Negro children overhead was most dreadful,” she wrote. “The air was rank and pestiferous with the exhalations from their bodies; and the language which fell upon the ear, and sights which met the eye, were too revolting to be depicted. . . . Emancipated from all control, and suddenly endowed with constitutional rights, they considered the exercise of their unbridled will as the only means of manifesting their equality.”

As the news spread about her incarceration, Rose became a curiosity, the oddest and most exotic creature in the jungle, expected to perform on command. Large parties of Yankees paid guards $10 for just a brief glimpse of the “indomitable rebel,” staring into her cell through the barred door. An editor from a Rochester journal tried flattery, telling Rose she had been detained because of her writing talent, which was on a par with that of Madame de Sévigné, a French aristocrat known for the wit and brilliance of her letters. Next descended a group of Boston society women, one of whom challenged: “Confess that it was love of notoriety which caused you to adopt your course, and you have been certainly gratified.” They called out to Little Rose, asking her to twirl around and say a few words.

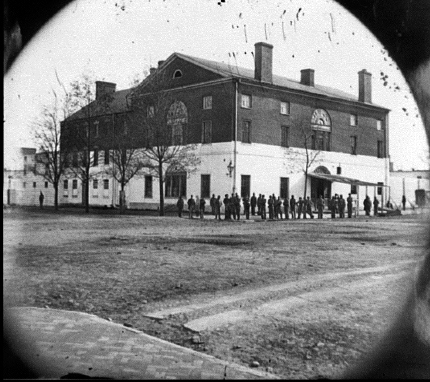

Rose and Little Rose in the courtyard of Old Capitol Prison, 1862, taken by Mathew Brady.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

(My little darling,” Rose whispered to her daughter, “you must show yourself superior to these Yankees, and not pine)

“Oh Mamma, never fear—I hate them too much,” Little Rose said. “I intend to dance and sing ‘Jeff Davis is coming’ just to scare them!”

The days slogged into weeks. At night Rose spent hours sifting through her daughter’s hair for bedbugs and burning them off the walls. They lay in squeamish silence, listening to rats scuttling across the floor. The straw bed prickled against their skin, and Little Rose wept against her neck: “Oh Mamma, the bed hurts me so much.” When she was able to sleep, she screamed herself awake from dreadful dreams. She was occasionally allowed outside to play in the prison yard, only to return in tears after the guards insulted her mother. The girl cried constantly from hunger. “To-day the dinner for myself and child,” Rose wrote, “consists of a bowl of beans swimming in grease, two slices of fat junk, and two slices of bread. Still, my consolation is, ‘Every dog has its day.’”

Little Rose awoke one morning in mid-February unable to rise from the bed, seized by a slow and nervous fever. Her tongue turned red, with matching spots sprouting across her chest and down her limbs, and her eyes were all pupils. Rose pressed her hand to her daughter’s forehead, noting that her “round chubby face, radiant with health, had become pale as marble.” She had camp measles, one of the fastest-spreading diseases; during the previous summer, one of every seven Confederates serving in northern Virginia had contracted measles, with more than eight thousand cases reported in three months. It could be fatal, leading to a collapse of the immune system and engorgement of the lungs, and Rose feared that her daughter was “fading away.” She thought of the Lincolns’ son, eleven-year-old Willie, on his deathbed from typhoid fever.

On February 18 she sent a letter to the provost marshal, begging for a visit from the family doctor, “unless it be the intention of your Government to murder my child.”

A few hours later the prison physician, Dr. Stewart, let himself into her room. “Madam,” he said, “I come to see you on official business.”

Rose positioned herself between Little Rose and the doctor, whom she silently nicknamed “Cyclops.” She did not trust this Yankee doctor to touch her daughter; she would hold out for her personal physician, even if it meant delaying Little Rose’s care. “Sir,” she replied, “I command you to go out. If you do not, I will summon the officer of the guard and the superintendent to put you out.”

The doctor stepped around Rose and started for the bed, where Little Rose lay shivering. Rose thrust out an arm. “At your peril but touch my child,” she warned. “You are a coward and no gentleman, thus to insult a woman.”

Stewart refused, his voice shaking as he spoke: “I will not go out of your room, madam.”

Rose pushed around him and pounded at her door. “Call the officer of the guard!” she shouted, and a lieutenant appeared. “Sir,” Rose said, “I order you to put this man out of my room, for conduct unworthy of an officer and a gentleman, and I will report you for having allowed him to enter here.”

The lieutenant glanced at the doctor, who was his superior officer, and back at Rose. He tried diplomacy: “I am sure Dr. Stewart will come out if you wish it.”

She shook her head. “Do your duty; order your guard to put him out.”

The doctor gave up. As soon as the door shut behind him she began to laugh, and the very sound of it—so strange and unexpected, and so long since she’d heard it—set her off again, pounding at the walls in bleak hysteria. “It was farcical in the extreme,” she wrote, “this display of valour against a sick child and careworn woman prisoner,” and she slid to the floor, giggling into her knees, giddy with the notion that the careworn woman had won.

Rose’s personal doctor visited and tended to Little Rose. The girl became herself again, eyes brightening and cheeks fattening, but Rose now sensed herself fading away. Her mind felt dim, slower to latch on to thoughts, and she developed a nervous tic, an involuntary jerking of the head. It was March, two months since she’d been taken from her home, with no resolution or even word of her case. She heard the guards boast about the Union’s recent capture of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in Tennessee, major victories for Ulysses S. Grant; Kentucky would remain in the Union, and now Tennessee was vulnerable to an invasion. Curious visitors still came to gawk and prod and taunt. A New York Times correspondent observed that her “vivacity is considerably reduced since her rebel plumage has been clipped with Yankee shears.”

As much as Rose loathed these intruders, she realized their potential value; they might divulge further news of the outside world if she asked sly enough questions. When her attempts failed, she summoned up all of her strength and pried loose a plank in the floor of her cell, creating a gap for Little Rose to slip through. Clutching her daughter under her arms, she lowered her to the cell below, which held Confederate prisoners of war. The men caught the girl by her legs, soon sending her back up with reports about the Union army.