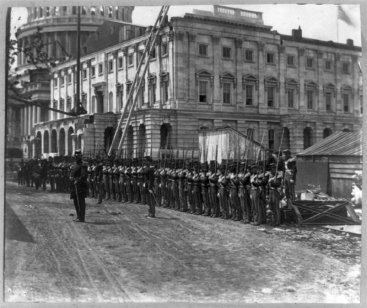

Soldiers in front of the Capitol, Washington, DC, 1861.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

By July 4, Franklin Thompson had been a Union soldier for six weeks, undergoing basic training in the Federal capital and waiting for orders to march on Virginia. He’d never expected to join an army or fight in a war—although a sharpshooter, he had yet to aim his gun at a man—but when President Lincoln called for volunteers, he posed the question to God, who made the decision for him.

Frank, as he preferred to be called, always believed that God was with him, protecting him even during—perhaps especially during—his transgressions. At night, after taps at 9:00 p.m., when the last light was extinguished and the last voice silenced, his mind sometimes conjured his most recent and serious trespass: the afternoon, six weeks earlier, when he took his place in line at Fort Wayne in Detroit, waiting for his turn with the medical examiner.

Official protocol of the US War Department dictated that all recruits strip and undergo a thorough physical examination, but doctors across the country flouted these rules. They had quotas to fill and needed bodies, quickly. It didn’t matter if a recruit was prone to convulsions or deaf in one ear or suffering from diphtheria. He merely required a trigger finger, the strength to carry a gun, and enough teeth with which to tear open powder cartridges. One recruit recalled the doctor pinching his collarbones and asking, “You have pretty good health, don’t you?” before passing him. Another was welcomed into the army after receiving “two or three little sort of ‘love taps’” on the chest.

Frank stepped forward. He was five foot six, two inches shorter than the average Union army recruit, solid but thin. He told the doctor he was nineteen years old, twenty come December. The doctor’s eyes skimmed his shoulders and back, torso and legs. He coiled his fingers around Frank’s wrist and lifted up his hand. He turned it over as if it were a tarot card, studying its nuances, noting the absence of calluses, the smooth palm, the slim and tapered fingers. For the first time he looked Frank directly in the eye.

“Well,” the officer said, “what sort of living has this hand earned?”

Frank was suddenly and strangely conscious of his voice. He willed his words to flow smoothly, to sound convinced of their own authenticity and tone. They would get him to the other side.

“Up to the present,” he replied, “that hand has been chiefly engaged in getting an education.”

Without further questioning the doctor marked Frank Thompson fit to serve as a private for Company F, 2nd Michigan Infantry. Frank took the oath of allegiance to the United States, solemnly swearing to Almighty God to support the Constitution and maintain it with his life. He assured himself that this was a calling, that he had to do what he could “for the defense of the right,” and that if he was careful no one would discover his secret: Frank Thompson was really Emma Edmondson, and had been posing as a man for two years.

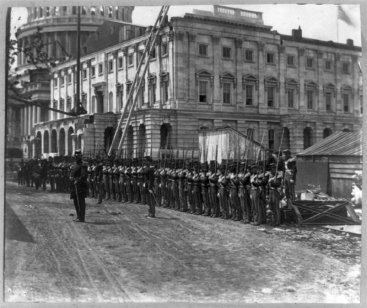

Emma Edmondson as Private Frank Thompson.

(Library and Archives, Canada)

Emma was one of fifty thousand Union soldiers currently in the nation’s capital, and she had never seen so many men in one place. Trainloads of fresh recruits clattered into Union Station each day; some came with pieces of rope tied to their musket barrels to use as nooses for Southern prisoners. Hotels overflowed with businessmen angling for government contracts and pursuing the city’s most eligible women. Soldiers lounged on the cushioned seats of the Capitol and reclined in easy chairs inside the White House. They spilled from the doorways of saloons and brothels and drove convoys of army wagons along the dusty streets. After dark, they accosted passersby in alleys for spare change and fired gunshots into the sky. Thousands of white army tents dotted the hills surrounding the city. Runaway slaves from Virginia and Maryland began slipping into the capital, and District police jailed those who lacked sufficient documentation of their freedom. The air reeked of garbage and manure and the contents of overburdened sewers. On July 4, she and the other recruits paraded for President Lincoln, who faced pressure to follow up the recent success in the Shenandoah Valley with a decisive attack that would end the rebellion.

In preparation they began each day at 5:00 a.m.: reveille, breakfast, and drills, endless drills: getting accustomed to orders and marching in columns; practicing how to “dress the line” by turning heads right or to the center; learning the drum and bugle calls that signaled whether to charge or retreat. “The first thing in the morning is drill,” one private complained. “Then drill, then drill again. Then drill, drill, a little more drill. Then drill, and lastly drill.” During the exercises the soldiers’ boots collected as much as fifteen pounds of mud and clay each. Emma kept pace with all of them; she was lithe and hard-muscled from a childhood spent working on the family farm. The city boys did not even know how to load their cartridges ball foremost, and she took furtive pleasure in teaching them. Members of the Seventh New York Infantry, known as the “silk stocking regiment,” had arrived in Washington with sandwiches from Delmonico’s and a thousand velvet-covered campstools on which to eat them. Many of the immigrant regiments—the Italian Legion, the German Rifles, the Steuben Volunteers—couldn’t understand orders in English. Some commanders conducted drills without live ammunition for fear that the neophyte troops would injure themselves before they even saw battle.

Over time Emma had become Frank Thompson—it was impossible to measure where one ended and the other began—but she now regarded her creation from a strange and subtle distance. Frank had never been tested this way, living in such tight quarters and under continuous scrutiny, and she grew keenly aware of each honed mannerism, the practiced and precise tenor of his voice. She took careful note of her comrades’ first impressions: they all knew that Frank hailed from Flint, Michigan, by way of Canada, and that despite his slight stature and oddly smooth face he had enjoyed a reputation as a ladies’ man before the outbreak of the war, squiring them around town in the finest horse and buggy, complete with a “silver mounted harness and all the paraphernalia of a nice turnout”—the fruits of a brief but successful career as an itinerant Bible salesman. They nicknamed him “our woman” and occasionally joked about his falsetto voice and small feet—so small he couldn’t wear standard-issue boots and had to bring his own—but they seemed to believe Frank was one of them, and considered him their equal. Emma liked to think they had more in common than not, the greatest distinction being that she had already died once and was willing to die again, this time for a cause much greater than her own.

If Frank faltered, Emma could be arrested and jailed. Even worse, in her mind, she would disappoint God and lose the chance to act in “this great drama,” as she liked to call the war. She was grateful for a few small mercies. To save time to prepare for roll call in the morning, most of the officers remained partially clothed for bed. Some even turned in wearing coats and boots, so no one would consider her odd if she didn’t strip down to her linens. She was lucky to count one tent mate as an old friend: Damon Stewart, a twenty-six-year-old shopkeeper from Flint, Michigan, whom she’d known before the war. They’d even double-dated on occasion, a history that now provided Emma some comfort; during downtime, gathered around the fire, her stories of sweethearts back home had a witness. Men were accustomed to seeing women in crinolines and bonnets and had no concept of what one would look like wearing trousers and a kepi cap. They could go for months without bathing or changing. Most of them avoided the long, filthy trenches that served as latrines and instead took care of “the necessaries” privately, in the woods. The stress and physical demands of her new role would almost certainly stop her menstrual cycle, and if she did bleed, her soiled rags could be passed off as the used bindings of a minor injury—hers or someone else’s.

Her smooth face and high voice were attributed to her youth, as was her disdain for swearing, drinking, and smoking. She had to be careful not to appear too adept at domestic skills like cooking and washing. Like the others, she sponged her plate with a piece of soft bread dampened with a few drops of coffee, or scoured it with dirt and rinsed it with her spit. Occasionally an enterprising officer would offer to clean or sew for others, charging a steep price, but Emma couldn’t afford to take the risk. It was the crucial details that might give her away.

She didn’t personally know any other female recruits, but she was not alone. As many as four hundred women, in both North and South, were posing and fighting as men. Some joined the army with a brother, father, sweetheart, or husband; one couple even enlisted together on their honeymoon. Some, like a twelve-year-old girl who joined as a drummer boy, were fleeing an abusive home situation. For poor, working-class, and farm women, the bounties and pay ($13 per month for Union soldiers, $11 for Confederates) served as an incentive. A small number of women had been living as men prior to the war and felt the same pressure as men to enlist. One Northern woman was a staunch abolitionist who fought because “slavery was an awful thing.” A Southern counterpart sought adventure, yearning to “shoulder my pistol and shoot some Yankees.”

Not so bloodthirsty, Emma had no intention of aiming her musket at any rebel, male or female. Every morning after roll call the medical staff had sick call, a task for which she eagerly volunteered. Believing there was a “magnetic power” in her hands to “soothe the delirium,” she tended to the soldiers suffering from typhoid fever and dysentery and the resulting chronic diarrhea, illnesses that would ultimately kill twice as many Union troops as would Confederate weapons. (“Bowels are of more consequence than brains” was a common jest.) She examined tongues and pulses, dispensed quinine and “blue mass”—a common compound of mercury—and offered “a little eau de vie to wash down the bitter drugs.” Once they received marching orders, she planned to work alongside army surgeons, hauling the wounded off battlefields, assisting with amputations, serving as the lone witness to whispered last words.

The last time Emma aimed her gun at any living being was two years ago, in 1859, before she’d ever imagined fighting in a war. She had just reinvented herself as Frank Thompson, selling Bibles door-to-door, and longed to see her mother, Betsy, who had no idea she was now living as a man. On one brisk October day Emma returned to the family farm in Magaguadavic, New Brunswick, dressed, ironically, in an army uniform, a cap tilted atop her tight brown curls. She approached the front door of her childhood home, introduced herself as Frank Thompson, and asked for something to eat. Betsy invited her inside and called Emma’s sister, Frances, to help prepare a meal for “the stranger.” Watching her sister, Emma glimpsed what her life would be had she stayed behind and bent to her father’s will. She would be married by now to her neighbor, the elderly widower who’d always watched too intently as she tended to her chores on the farm.

Emma’s brother, Thomas, sat down to join them. Her father, Isaac—“the stern master of ceremonies of that demoralized household”—was not around. Years earlier he had gone about selecting a wife who would be a good breeder in much the same way he chose a female animal for a stud, hoping to raise a large family of sons to help grow potatoes, the most important crop for New Brunswick farmers. Instead his wife gave birth to four daughters in quick succession and a son who suffered from epilepsy, an affliction Isaac viewed with disgust. He had always been prone to violent rages, a tendency that increased with the birth of each child, and when Betsy became pregnant in 1841 for the sixth and final time, she prayed every day for a boy. Instead, on a cold December day came Sarah Emma Evelyn, Emma for short. Betsy wept as the midwife cleared away the evidence of her betrayal. “My infant soul was impressed with a sense of my mother’s wrongs,” Emma later said, “although I managed to outgrow it immeasurably.” She learned to hunt and fish and break wild colts, trying her best to be the boy her father wanted, but never heard one word of praise.

Emma was relieved by his absence, and after an hour or so of idle chat, Betsy turned to Frances and without warning began to cry. “Fanny,” she said, “don’t you think this young man looks like your poor sister?” At this, Emma rushed to kneel beside Betsy and asked, “Mother, dear, don’t you know me?”

Betsy stared at her. She removed Emma’s cap and ran her fingers through her hair. One fingertip trailed down her daughter’s face. “No,” she said, “you are not my child. My daughter had a mole on her left cheek, but there is none here.”

“Mother,” Emma replied, “get your glasses and you will see the scar. I had the mole removed for fear I might be detected by it.” She jumped up to retrieve the glasses herself, reveling in her mother’s reaction: “She cried and laughed both at once, and I caught her up in my strong arms as if she were a baby, and carried her around the room, and held her and kissed her until she forgave me.”

Emma stayed as long as she dared, glancing frequently at the door, fearing that her father might walk in at any moment. Her family assured her they would say nothing of the visit, lest Isaac Edmondson set off to hunt his daughter down. Thomas accompanied his sister to the train depot, and along the way they spotted six partridges. He had never learned how to handle a gun. One by one Emma shot the birds herself, cleanly in the head, and gave the quarry to her brother to take home.

She would lose her aversion to shooting rebels sooner than she could have imagined.

Despite their inexperience Emma and her fellow recruits were eager for action; they worried that the war would be over before they even had a chance to meet the enemy. Lincoln agreed that it was time. Every day Horace Greeley, the outspoken and influential editor of the New York Tribune, egged him on with the same bold headline: “FORWARD TO RICHMOND! The Rebel Congress must not be allowed to meet there on the 20 of July! By that date the place must be held by the National Army!” The fighting in the Shenandoah Valley had made headlines but resolved little, and the Union army had a tentative plan: Major General George McClellan, the commander of the Department of the Ohio, would bring his troops eastward to support General Patterson in Martinsburg, Virginia. Together they would prevent Confederate forces from leaving the Valley to reinforce Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard at Manassas, twenty-five miles west of Washington. Brigadier General Irvin McDowell, commander of the Union troops around the capital, would dispose of Beauregard and push on to Richmond. A Union victory at Manassas and the capture of the Confederate capital would effectively crush the rebellion.

But McDowell was not yet ready to fight. He had an undersized staff and didn’t even possess a map of Virginia that showed anything beyond the main roads. Most of his recruits were ninety-day volunteers and still too ill trained to go to war.

“This is not an army,” he warned President Lincoln. “It will take a long time to make an army.”

“You are green, it is true,” Lincoln replied. “But they are green, also; you are green alike.”

It was decided: thirty-seven thousand Union recruits, Emma included, would soon march onward to Virginia. “No gloomy forebodings,” she wrote, “seemed to damp the spirits of the men.” They looked, to her, as though they had an overabundance of life, and all that life was darting about inside them, making every word louder and movement quicker. How “many, very many” of them, she wondered, would never go home? She felt suddenly and strangely out of harmony, but Frank Thompson buoyed her along.