Just as McClellan was about to order the first “decisive step” of the final advance on Richmond, he received another ominous report from Pinkerton. Under interrogation, a deserter from Stonewall Jackson’s command had revealed that Jackson’s entire force, still en route from the Shenandoah Valley, would attack Union general Fitz John Porter’s corps on the north side of the Chickahominy River. McClellan nevertheless kept to his plan, ordering two divisions to advance just twelve hundred yards, taking a dense oak grove that sprawled between the Union and Confederate front lines.

Emma’s regiment was held in reserve, but she could feel the heat of the gunfire and see the men in the rifle pits, muddy water up to their knees, looking like “fit subjects for the hospital or lunatic asylum.” By late afternoon she heard voices rise high and clear, the ringing cheers of the Union laid over the sharp, wild yip of the rebels, a malevolent refrain on endless repeat. When it finally stopped, Union troops had given McClellan half of what he wanted—six hundred yards, gained at a cost of one casualty per yard.

The general declared that his men had “behaved splendidly” at Oak Grove, the first of what would become known as the Seven Days Battles, but two hours later found himself in a panic. A fugitive slave, newly escaped from Richmond, reported that rebel officers boasted of two hundred thousand troops ready for the “big fight,” prompting McClellan to telegraph Washington: “I regret my great inferiority in numbers, but feel that I am in no way responsible for it. . . . I will do all that a general can do with the splendid army I have the honor to command, and, if it is destroyed by overwhelming numbers, can at least die with it and share its fate.”

In reality Lee had just eighty thousand men and was taking an enormous risk throwing fifty thousand of them at McClellan’s right flank, leaving a mere thirty thousand to defend Richmond—less than half of the Union force now surrounding the Confederate capital. His plan depended on precise timing, flawless coordination between his generals, and a belief that McClellan would fail to capitalize on his numerical advantage and instead cower under the rebel assault. Lee would strike the following morning, at first light.

But Stonewall Jackson was late, delayed by exhausted troops and confusing, vaguely mapped roads through the thick lowlands, and Lee had to move without him. At last, at 4:00 p.m. on June 26, a dozen guns sounded by the Chickahominy, the booms melding into thunder, as many as forty shots per minute. Emma’s division was near the front line and she heard the rebels before she saw them—again that feral, primal yell that evoked the cry of hounds on the scent.

Elizabeth heard it, too, riding in her carriage to Henrico County, just northeast of the city, to visit her Unionist friend John Minor Botts. “The excitement on the Mechanicsville Turnpike was more thrilling than I could conceive,” she wrote that night in her diary. “Men riding and leading horses at full speed; the rattling of their gear, their canteens and arms; the rush of the poor beasts into and out of the pond at which they were watered. The dust, the cannons on the crop roads and fields, the ambulances, the long line of infantry awaiting orders . . . I realized the bright rush of life, the hurry of death on the battlefield.” The windows of Botts’s home rattled without pause, offering a view of bursting shells and dingy coils of smoke. She still kept McClellan’s room—the charming spare chamber with the pretty curtains—ready for him, complete to the water drawn for his bath.

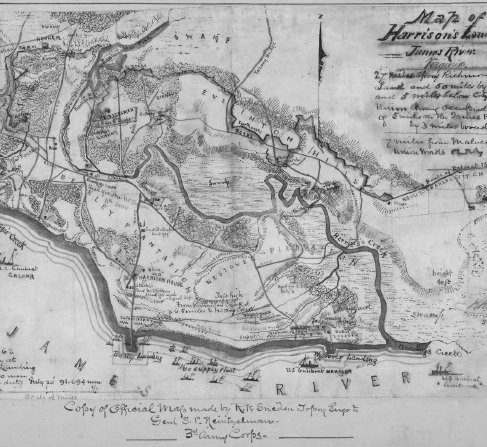

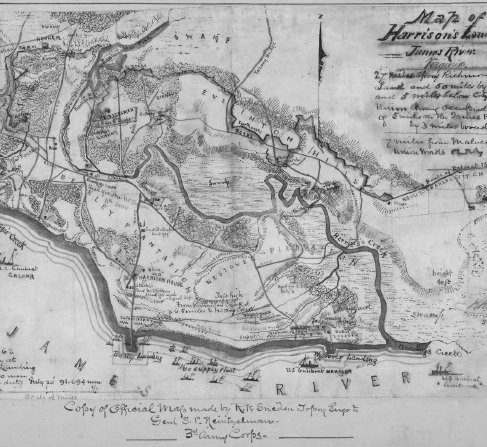

The battle of Beaver Dam Creek at Mechanicsville lasted six hours and culminated in a Union victory, 361 casualties to the rebels’ 1,484, and McClellan sent a triumphant wire to Washington: “I almost begin to think we are invincible.” He changed his mind after learning that Stonewall Jackson had finally arrived, but not in time to fight—which meant that his right flank had faced only a portion of Lee’s force, and that the rebels were sure to attack again the next day. Although the Confederates were disorganized and outnumbered, and Richmond was more vulnerable than ever, McClellan decided that his most imperative goal was to move his base of operations from White House Landing on the York River to Harrison’s Landing on the James River, which snaked along the downtown neighborhoods of Richmond. Once he was settled there, he reasoned, he could refocus his attention on the Confederate capital. He would call it not a retreat but a change of base—“one of the most difficult undertakings in war.”

But a retreat it was. Lee began chasing the 120,000-man Army of the Potomac, with its wagons and supply trains, its guns and provisions, even its 2,500 head of cattle, as it fled south to the safety of the James. On the third day, as Lee battered Union forces north of the Chickahominy, Emma volunteered to warn surgeons, nurses, and all ambulatory patients to flee as soon as possible or else risk falling “into the hands of the enemy.” All morning she rode from one hospital to another, repeating these words, shouting over the percussion of gunfire, desperate to reach the one person who mattered.

She found Jerome Robbins just after noon at his hospital in Talleysville. He looked older than he was, overtired and dusty. She was conscious of her own flushed face and dampened hair, the wild, spinning panic in her eyes. He had to leave, she told him. They were coming, closer and closer. They were out there now—listen. He refused to leave his patients. She tried again, screaming now. Still he refused. She left him there, standing by the beds, guarding the neat rows of mutilated men, and found her way back to the river.

The rebels chased the Union army through the marshy muck of White Oak Swamp, two days of marching with no food or sleep, until they reached Malvern Hill, eighteen miles southeast of Richmond. There they got busy building defense works and positioning more than 250 guns until the men finally collapsed—all except the guards, who paced back and forward in front of the line, ready to arouse the sleepers at any moment. Emma awoke to the sound of cannon and the battle raged all day with terrible fury: “hour after hour, the enemy advancing in massive column, often without order but with perfect recklessness; and the concentrated fire of our gunboats, batteries, and infantry mowing down the advancing host in a most fearful manner, until the slain lay in heaps upon the field.” General McClellan, meanwhile, was safely ensconced on a navy gunboat on his way to Harrison’s Landing, just six miles downstream from Elizabeth’s family farm.

Elizabeth was quietly furious about the Union retreat. Richmond should have fallen; the war should be over. She should be celebrating Independence Day by unpacking her Union flag and raising it over her home. Instead her neighbors wore supercilious smiles and spoke in pious tones, asking for donations for the Confederate bazaar at Ninth and Broad Streets, or for the “Ladies Aid and Defense Association,” which raised funds for the construction of a gunboat to defend the James River. Elizabeth found the whole enterprise “supremely ridiculous,” and consoled herself by working harder on behalf of the Union.

Increasing numbers of escaped officers were finding their way to her home, or to one of many Union safe houses she’d established, through her money and connections, in and around the city. She supplied all of the men with food, clothing, and forged exemption tickets, which identified them as employees on Confederate government contract works, and her servants guided them toward the Northern lines, keeping watch for pursuing cavalry. Once the escapees made it to Union territory, they headed straight to McClellan’s headquarters, reporting prison gossip about the rebels and their plans. Now, with McClellan stationed at Harrison’s Landing, so close to her family’s vegetable farm, Elizabeth devised another way to pass on information about the enemy. Her connection—Mary Jane Bowser’s husband, Wilson—was already set up at the farm on the other end, but any number of things could go wrong before her dispatches made it that far.

One afternoon in the first week of July she sequestered herself in her library, a straight pin between her fingers and a book on her lap, chosen not for its text but for the quality of its pages: clean and stiff, with no dog-ears, tea stains, or rips. She had to be careful to hide her actions from her nieces, now eight and five years old. Their mother had recently told John she did not want her children being raised by any “damned Yankees,” an intended slight against both her husband and Elizabeth. Mary kidnapped the girls; fled to her family’s estate, Bellefield, just outside the city; and went on a celebratory bender—what Elizabeth called a night of “awful sin.” John rescued the kids, bringing them and their “mammy” to live permanently at the Church Hill mansion. It was a terrifying, traumatic event, and Elizabeth wanted to return some peace and routine to the girls’ lives, insomuch as peace and routine were possible during a war.

They were smart, curious girls, always asking questions about what was happening to their city, counting the charges of musketry as if they were raindrops tapping the roof, noticing the people who crossed to the other side of the street rather than acknowledge their aunt. Once, unbeknownst to Elizabeth, Annie followed her upstairs on tiptoe, watching her disappear into the secret room at the end of the hall. When her aunt crept back downstairs, Annie went to investigate. She found the door to the room slightly ajar. Peeking behind it she saw two men, foul-smelling, faces streaked with dirt. One of them pressed a grimy fingertip to his lips.

“Keep it all a secret,” he whispered, “or else we will die.”

Annie backed away slowly and pushed the door closed. When she checked the room the next day, the men were gone.

Now the girls sat by Elizabeth’s feet, wondering why their aunt was sticking a pin through the pages of her book. Elizabeth asked Annie if she would take her sister to her room and play quietly for a while; if they needed anything, they could find Grandma. Her niece obeyed, and she was alone again.

She began on page 1, poking precise holes into a sequence of letters, the letters forming words, the words forming requests: Give me the names and ranks of imprisoned officers. Are you hearing anything about Confederate troop numbers and movements? About Lee’s plans? About Confederate forces in Manassas? Satisfied, she asked a servant to load several items into her carriage: a table, an armchair, a looking glass, a dozen new towels, pen and ink, paper. She carried her book and a bundle of clothing, making sure to leave pins pushed through the collars, and asked her driver to take her to Libby Prison, Twentieth and Cary Streets. Officials still forbade her to enter the prison proper but gave her access to its hospital, the first room on the east side.

She alighted from her carriage, carrying the books and clothing, being careful not to disturb the pins in the collars. Her servant stayed behind, unloading the rest of the items to drop off at the main prison. A man stood by the doorway. As far as Elizabeth could tell, he was a civilian—he wore no rebel uniform—but he held up a hand in a way that made her stop.

“Are any of the prisoners related to you?” he asked.

“No,” she answered, and pulled her package closer.

“Are you acquainted with any of them?”

She glanced skyward toward the prison’s upper floors, where the windows offered a clear view of the bridges across the James River to Manchester, from which trains departed south and west. The men had nothing but time, which they spent playing endless games of cards, covering the walls with graffiti (“The Union Must Stand and Shall Be Preserved” was a favorite slogan), and whittling a variety of items from soup bones: pipes, spoons, crosses, chess pieces, intricate earrings and brooches for their sisters or wives. They could easily keep watch out those windows, looking for things of interest to Washington.

“I do not know any of them,” Elizabeth said. “I visit them on the grounds of humanity.”

The man shook his head once, back and forth. “You could show your humanity better by visiting our sick soldiers around the city.”

She lifted her chin and spoke with calm certainty: “The Bible states we must visit our enemies.”

“But it does not say we must visit them before visiting our sick friends.”

She assured the man that she had charitable intentions to spare, slid past him, and headed left to the hospital.

Scanning the room, she memorized the layout, noting the proximity of the guards. In one far corner a small partition concealed medicine and supplies. Four rows of cots extended the entire length of the space, all of them occupied by sick and wounded men. She found an officer who seemed awake and alert, his eyes flitting in her direction as she sat next to him. She thanked him for his service and said how honored she was to bring him and his fellow inmates some new clothing; he must excuse her if she inadvertently left some pins in the fabric. Then she placed the book in his hands, floated her mouth by his ear, and whispered, “Read the pinpricks.”

A few days later Elizabeth retrieved the book and transcribed the answers—information about imprisoned soldiers and scuttlebutt from the rebel guards—connecting the dots letter by letter, word by word, sentence by sentence. She crept out to the stables and slipped the letter beneath the driver’s seat of a wagon. One of her servants would make the trip to the farm. He would be unaware that he was carrying anything but manure; she wanted to involve as few people as possible for as long as possible. At the other end Mary Jane’s husband would be waiting, and knew exactly what had to be done.

General McClellan established headquarters at Berkeley Plantation on Harrison’s Landing, six miles downstream from Elizabeth’s family farm.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

That night, lying in bed, Annie and Eliza sound asleep, Elizabeth pictured it as it happened: Wilson Bowser, message hidden in his shoe or inside his drawers, lowered himself into a rowboat and pushed off, drifting in midriver under a pale and lusterless moon. He coasted to the Union gunboats patrolling near the Appomattox-James confluence, holding up his hands to show he was unarmed. He explained to the officers that he had a note for the Union high command from a knowledgeable source in Richmond, information that needed to be delivered to Harrison’s Landing right away. The dispatch was sent up the chain, landing, hopefully, in the hands of a Union colonel Elizabeth never named, an old family connection from the North.

Over the next few weeks Elizabeth learned that a portion of Lee’s army had begun to move away from Richmond and toward northern Virginia, threatening Union troops at Manassas. If McClellan vacated Harrison’s Landing to reinforce them, she would have to establish another route for her dispatches. And considering the Union’s faltering performance on the Peninsula, those dispatches should contain more reliable and vital information than what she’d gleaned from prisoners. She needed to connect with Mary Jane Bowser and finally turn her servant into a spy—a much riskier prospect now than it was last year: one mole in the Confederate White House had already come to light.

Jefferson Davis’s enslaved coachman, William Jackson, had recently escaped from his employers and fled to Union lines at Fredericksburg, Virginia. During a meeting with Secretary of War Stanton, he provided information about the rebel army that could have come only from inside the Confederate White House and gave interviews to the Northern press, calling his former boss sickly and irritable and Varina a devil. Elizabeth knew that the Davises would from now on keep a wary eye on other servants. One small indiscretion could lead to Mary Jane, and that would implicate Elizabeth.

Nevertheless she strolled across the street to Eliza Carrington’s home to meet with her friend’s seamstress, whose name no one ever divulged. Elizabeth inquired about Mary Jane’s schedule, wanting to know which days and times she dropped off the First Lady’s dresses. She told the seamstress she’d return soon, on a day her servant would be there.

A few days later, while she was walking through Church Hill, a man dressed in civilian clothing fell into step beside her. She lifted her skirts an inch, picking up her pace.

He kept up with her. His voice was a gruff whisper: “I’m going through the lines tonight. Do you have anything for me?”

She stopped and turned, facing him straight on. She had never seen him before but she knew what he was, and what he was trying to do. She shrugged and walked on, muttering to herself, as if she hadn’t understood a word he said.