Rose O’Neal Greenhow, circa 1861.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

As soon as Emma received her marching orders, Rose O’Neal Greenhow summoned a courier to her home at Sixteenth and K Streets near Lafayette Square—“within easy rifle range of the White House,” as her friend, Confederate general Beauregard, liked to joke. She had to warn him that the enemy was coming, that swarms of Yankee soldiers would soon be filing from the city and heading to Manassas, Virginia, ready to fight the first major land battle of the war. The courier, Bettie Duvall, was just sixteen years old, but Rose trusted her to make this delivery. Bettie was a Washington socialite, the daughter of an old family friend, but for this mission she would play the part of a simple farm girl returning from the market, a disguise unlikely to arouse suspicion among Union guards. The Confederacy was counting on Rose to provide intelligence about the enemy’s plans, and she needed to secure a victory for the South. The new nation would not survive if the rebel army lost.

Rose led Bettie to her vanity and pulled the girl’s hair as if it were a bridle, cinching the strands around her wrist. Her other hand held a purse stitched of the finest black silk. After her husband’s death seven years before, she’d used the same silk to make a mourning dress—a dress she now wore again in memory of her twenty-three-year-old daughter, Gertrude, who’d succumbed to typhoid fever two weeks after Lincoln’s inauguration. Gertrude was her fifth child to die—she’d lost four within three years—and she had three daughters left but only one living at home. Little Rose, the third daughter she’d named after herself, was eight years old, and would become an important part of her plans.

She buried the purse in Bettie’s hair, coiling it into a tight cocoon and clasping it with a comb. The hair would not come undone until Bettie arrived at Beauregard’s headquarters and shook it loose.

Rose gave the girl meticulous instructions: Wear this tattered calico frock and drive a milk cart along a dirt road on the Washington side of the Potomac River. Pass by the endless stretch of Union camps—the 1st Massachusetts, the 2nd Wisconsin, the 2nd Michigan—and, after the last, veer left onto the Chain Bridge. Union artillerymen will be perched atop their fortification, guarding the area, but she should just proceed calmly, passing into Virginia as if she has nothing to hide. Once she reaches the countryside, she must be wary of Yankee scouts and pickets; it would probably be best to stop somewhere for the night.

In the morning, she’ll continue on to Beauregard’s headquarters at Manassas Junction. Tell the Confederate pickets she has important information for the general. Once inside, unwrap her chignon and deliver the contents of the silk purse: a slip of paper with a coded message: “McDowell has certainly been ordered to advance on the sixteenth. ROG.” The Confederates would understand that the Union forces under Irvin McDowell planned to leave Washington for Manassas one week later. Rose had gotten the information from a “reliable source,” possibly a high-ranking Northern official, who had a copy of the order to McDowell. Another source provided her with a map, used by the Senate Military Affairs Committee, showing the Union army’s route to the battlefield.

Rose had been the head of the city’s Confederate spy ring since April, when Captain Thomas Jordan, a West Pointer, distinguished veteran of the Mexican-American War and quartermaster in the US Army, came to call on her. Jordan was forty-one, six years younger than she, with close-set eyes and a tangled beard. She invited him into her back parlor, pulling a curtain of red gauze behind her, and offered him tea. She sensed he did not wholly trust her; she had earned her nickname, “Wild Rose.”

Jordan, like the rest of Washington, had heard gossip about her late-night gentlemen callers: abolitionists, secessionists, senators, representatives, diplomats, and even their lowly aides. Perhaps he had heard similar gossip about himself, rumors that he enjoyed “the same kind of intimacy” with her. If Jordan stayed late, she might replace the tea with brandy. She might unwrap her own chignon, letting her black hair skim the small of her back.

Jordan told her he had decided to switch sides to fight for his native Virginia and needed to create an espionage ring in the Federal capital—a ring he wanted Rose to organize and oversee. He and President Jefferson Davis considered her the ideal candidate for the job, both despite and because of her occasional indiscretions, and Rose accepted on the spot. No woman in Washington knew more men of power and influence, of both the Northern and the Southern persuasion.

In 1835, at age twenty-two, she’d married Dr. Robert Greenhow, a physician and scholar who served as a high-ranking official in the State Department. His tenure spanned twenty years and seven presidential administrations, and over time Rose became a greedy prospector of the powerful. She dined with Martin Van Buren and counted the late former vice president John C. Calhoun as a mentor. An avid proponent of slavery, Calhoun would sip old port and muse about the South’s “peculiar institution,” insisting it was “indispensable to the peace and happiness” of the entire country and a “positive good.” Rose worshipped him, calling him “the best and wisest man of this century,” and let his politics shape her own. She served as a close confidante to President James Buchanan and attended masquerade balls with then Mississippi senator Jefferson Davis. The New York Times, in reviewing one such event, declared her “glorious as a diamond richly set.”

As Washington became increasingly polarized over the issue of slavery, the Greenhows considered settling in the American West to prospect in land and gold. In February 1854, during a trip to San Francisco, Robert slipped off a section of planked road and fell six feet to the ground, badly injuring his left leg. An infection set in and he died six weeks later. Rose learned of the news in a letter from the head of the California Land Commission: “Robert Greenhow Esq,” it read, “is no more.” Little Rose was only ten months old.

After Robert’s death Rose strove to maintain her social position and relevance by any means necessary, disregarding neighbors’ catty talk about her “confidential relations.” She heard whispers that her “widowed tears were soon dried up” by the $10,000 settlement she received from the City of San Francisco (money she lost speculating in stocks). Although there was no relation, some compared Rose to the notorious Peggy O’Neale Eaton, who reportedly cheated on her husband and wed too soon after his death; this second marriage, to a Tennessee senator and adviser to Andrew Jackson, led to the dissolution of that president’s cabinet. But like Peggy, Rose retained numerous admirers, men who appreciated her wit and savvy as much as her figure, who knew she needed no one to come to her defense. Confederate naval secretary Stephen Mallory marveled at the way she “hunted man with that resistless zeal and unfailing instinct . . . she had a shaft in her quiver for every defense which game might attempt.” Union colonel Erasmus D. Keyes called her “one of the most persuasive women that was ever known in Washington”—persuasive enough to wheedle classified information from him in between their alleged trysts. Next came Senator Joseph Lane, Democrat from Oregon, who came to call on her as often as his health would allow. “Believe me, my dear, I am not able to move as a young man should,” he wrote. “Please answer.”

Rose’s latest conquest was Henry D. Wilson, an abolitionist Republican senator, Lincoln’s chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs, and future vice president. Wilson was a particular challenge, said to be devoted to his wife and reticent with his opinions. Rose lapped at him with her questions, increasing their force and frequency, smoothing his resistance and wearing down his will, a process that felt more like erosion than seduction. Afterward he allegedly sent torrid letters, some written on congressional stationery, all signed only “H.”

“You know that I do love you,” read one. “I am suffering this morning. In fact I am sick physically and mentally and know nothing that would soothe me so much as an hour with you. And tonight, at whatever cost, I will see you.”

If “H” was indeed Wilson, he was fully aware of Rose’s secessionist proclivities and apparently didn’t care. The letters contained no breach of national security, but neither he nor Rose ever divulged what was said behind closed doors.

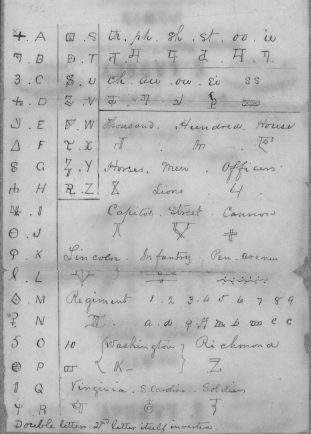

Jordan taught Rose a rudimentary cipher of the type used in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Gold-Bug,” in which mysterious-looking symbols each conceal a different letter, number, or word. She was to address all correspondence to his alias, Thomas J. Rayford. Certain combinations became familiar: “Infantry” was two parallel lines adorned with small circles; “Pennsylvania Avenue,” a series of squiggles framed by dots; “President Lincoln” (whom Rose alternately called “Beanpole” and “Satan”) looked like an inverted triangle bisected by a single slash. Jordan pointed out that the upper windows on one side of her home were easily visible through a telescope on the Virginia side of the Potomac. He gave her a copy of the Morse code and demonstrated how to manipulate the window shades to indicate dots and dashes. Each day at 10:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m., he would order a scout or picket to watch the windows for any important news. On the street she could achieve the same effect with precise flutterings of her fan.

Rose Greenhow’s cipher.

(National Archives)

Rose immersed herself in her new role. Days that had once been spent shopping and making social calls to other women—the same women who gossiped about her late-night visitors—were now devoted to practicing her cipher and plotting her next move. The work overtook her mind, muting the dull, relentless drumbeat of thoughts about what her life had become. She was a widow with no steady income, forced to take seamstress jobs and put up furniture as collateral for rent money. With the end of the Buchanan reign and nearly thirty years of Democratic rule she’d lost her place as the doyenne of Washington society. Her daughter Florence, who was married to a captain in the Union army, sent carefully worded letters pleading with her to choose a different path: “I am so much worried about the latest news from Washington. They say some ladies have been taken up as spies. . . . Dear Mamma, do keep as clear of all Secessionists as you possibly can. I so much fear everything for you all alone there.” Her very way of life was in danger of extinction, with the Yankees intent on liberating those Negro “beasts of the field.” This war was the only hope of restoring her past and securing her future, and she would employ “every capacity with which God has endowed me” to aid the rebel cause.

She understood that the Confederate espionage system had certain advantages, circumstances she could exploit to gather intelligence. Washington, DC, was a Southern city in both character and origin; a third of its residents had been born in the slaveholding states of Virginia or Maryland. In Maryland, the Lincoln ticket received less than 3 percent of votes cast; in Virginia, barely 1 percent. Nearly every member of the Confederate government had once been a Federal official and, as such, possessed intimate knowledge of government operations. Jefferson Davis himself had served as secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce. Even the city’s mayor, James G. Berret, was said to “smack of sympathy with secession.”

The office of Attorney General Edwin M. Stanton, soon to be Lincoln’s secretary of war, was so riddled with Southern sympathizers that he had to walk to its entryway to speak confidentially with a Republican senator. Even the White House was vulnerable, more or less open to any citizen seeking a meeting with the president, who held court in a second-floor office behind a pigeonhole desk. Mary Todd Lincoln, a Kentuckian with a brother, three half brothers, and three brothers-in-law in the Confederate army, once discovered that a Southern guest was in the habit of eavesdropping outside the cabinet room doors. Such ill-gotten information would be delivered via the Underground Railroad—not, in this context, a secret route for escaped slaves but a complicated chain of couriers, boats, and horses connecting Baltimore and Washington with Richmond.

The Confederate government had no fund set aside to employ spies, but volunteers abounded, and the willingness to work without payment was a test of sincerity and loyalty. Rose had to choose carefully; the currently disorganized nature of Union intelligence did not preclude a savvy spy or two from gathering information to use against the rebels. At least one Union agent, who secretly worked as a telegraph operator, had ingratiated himself with Beauregard, persuading the general to introduce him at the Manassas Junction station as “a railroad man willing to undertake any work you may have for him to do.” Meanwhile, he was already busy sweeping out the telegraph station, listening to every message that came in.

In early May, as Union troops began to arrive in Washington, Rose began assembling her network. She called them her “scouts” but they were technically spies, the difference being that a scout was an official member of the army and a spy was a civilian. If a scout was captured, he would be treated as an enemy combatant, while a spy would be summarily hanged. Her group included a lawyer with roots in South Carolina; a clerk in the Post Office Department; a dentist who, during frequent visits to his son in the Confederate army, delivered messages and documents; a banker who traveled throughout the South under an assumed name; a professor, a cotton broker, an opium smoker, and a Sister of Charity; a widow who agreed to deliver messages for the money, completely ignorant of the true nature of her job; and various society women who had known Rose for years and their young daughters, among them Bettie Duvall, who, on July 9, began the journey from Washington to Beauregard’s headquarters, carrying news of the enemy’s plans.

Bettie rode her farm cart through Georgetown, passing by a series of Union camps, a thread of canvas tents stretched as far as she could see. Bold curls of black smoke spiraled toward the sky, carrying the scents of grease and burned sugar. She heard the jumpy plink of a banjo, the hypnotic skip of a fiddle. Confederate and Union soldiers sometimes exchanged fire across the river, but she refrained from snapping her reins to push faster; panicking would only draw attention. She turned left and rattled onto the rickety boards of Chain Bridge. If she peeked upward, past the brim of her bonnet, she would see the Union artillerymen at Battery Martin Scott, a two-tiered stone-and-turf fortification overlooking the bridge. Iron twelve-pounder guns mounted at the end of the bridge could sweep the span, and three forty-two-pounders loomed a hundred feet up the hill. No one stopped her as she rumbled across, pushing into the Virginia countryside. She had left Rose’s home hours earlier and was still not even halfway to her destination.

At sundown Bettie worried about Yankee scouts and pickets; she, like Belle Boyd, had heard of “Yankee outrages” against women. For safety’s sake Bettie stopped for the night at Sharon, a plantation owned by a family friend just west of the village of Langley. In the morning she shed her calico dress for a riding habit, abandoned the cart, and borrowed a saddle horse. She cantered off, passing abandoned wood houses and weathered ox fences, reaching a Confederate outpost near Vienna. The provost marshal brought her to Beauregard’s top aide, Brigadier General Milledge Luke Bonham, who was surprised to see the “beautiful young lady, a brunette with sparkling black eyes, perfect features, the glow of patriotic devotion burning in her face.” Bettie told Bonham she had important information for Beauregard. Would he receive it and forward it immediately? If not, might she deliver it herself?

Bonham promised that he “would have it faithfully forwarded at once.”

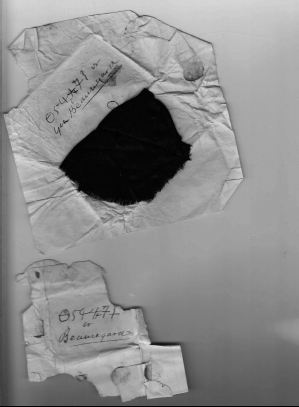

Satisfied, the girl took out her tucking comb and let fall the “longest and most beautiful roll of hair” he had ever seen. From the back of her head she retrieved a small package, not larger than a silver dollar, sewed up in silk. Without checking its contents, Bonham rushed the packet to Beauregard, who sent it by courier to Jefferson Davis.

A piece of Rose Greenhow’s silk purse and part of an encrypted message.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

On July 16, six days after Bettie’s delivery, Rose felt a hand press on her shoulder. She awakened to see her maid, Lizzie Fitzgerald, who whispered that a gentleman was at the door. Rose tightened her dressing gown, checked on Little Rose sleeping in her room, and hurried down the stairs. The night had thinned and the sky cracked open a dim yolk of sun, lighting a familiar face: George Donnellan, former clerk at the Department of the Interior and a close associate of Thomas Jordan’s. As an extra precaution, Rose requested further identification. Without a word Donnellan dropped a crumpled scrap of paper into her hand. She closed her fingers around it as she raised it to her eyes. Just two words, written in her cipher, but the two words she needed to read:

Rose nodded, the messenger stepped inside, and they closed the city out.

She hurried to her library, sat down at her desk, and conjured the proper symbols for her next enciphered message, confirmation of the intelligence she’d sent a week earlier:

“Order issued for McDowell to march upon Manassas tonight. The enemy is 55,000 strong.”

Donnellan stuffed the message into the hollowed-out heel of his boot and scuttled out the door. Once he disappeared around the corner of Sixteenth Street, Rose pictured the rest of his route: a few miles by buggy, a few more on horseback, down the eastern shore of the Potomac to a ferry in Charles County, Maryland, where he crossed into Virginia and handed the message to a Confederate cavalry officer, along with these fervent instructions: “This must go thro’ by a lightning express to Beauregard.” Confederate troops stationed along the Potomac included fifty-eight cavalrymen ready to participate in a relay system designed for maximum efficiency. Stations were ten to twelve miles apart, with fresh horses available at each, and by 8:00 p.m. Beauregard was studying Rose’s deciphered note. Within a half hour the general telegraphed the information to President Jefferson Davis. The Southern army had a few days to prepare before the enemy arrived.

The following morning, Donnellan returned to Rose’s home with Jordan’s reply: “Let them come. We are ready for them.”