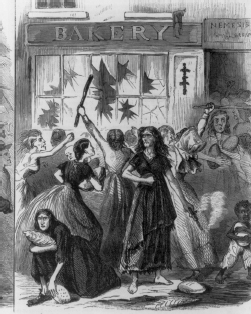

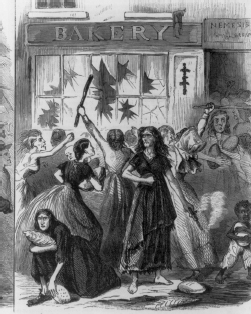

Illustration of the Richmond bread riot, April 1863.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

On March 27 Jefferson Davis declared one of his numerous “fast days,” in which he called upon the citizens of the Confederacy to attend church and abstain from food and drink. On such occasions Elizabeth and her family instead enjoyed a better dinner than usual and even sweet tea and dessert; brother John frequently returned from his trips north with sugar, a rare delicacy in these long, lean days of the blockade. Guilt always accompanied this act of defiance, as Elizabeth heard stories and witnessed firsthand how Southerners were starving. In Atlanta a dozen women held up a butcher shop, brandishing guns and escaping with armfuls of meat. In Richmond a war clerk complained that he had lost twenty pounds, and his wife and children were emaciated. In Vicksburg, Mississippi, people turned to eating rats, dogs, and cats, and a local newspaper wrote of “the luxury of mule meat and fricasseed kitten.” One mother fed her daughter soup containing the remains of the girl’s pet bird.

“Alas for the suffering of the very poor!” Elizabeth wrote in her journal. “Women are begging with tears in their eyes, and a different class from ordinary beggars . . . There is a starvation panic on the people.”

Such circumstances, to her thinking, had but one positive effect: declining morale among the populace aggravated declining morale among the entire Confederate army.

The events of April 2, less than a week after the last fast day, unfolded as if Elizabeth had choreographed every moment, starting with a young girl waiting on a bench in Richmond’s Capitol Square, her body a rigid structure of stark angles and jutting bones. She turned to an old lady sitting next to her, said she was too weak to stand, and raised a skeletal arm to adjust her bonnet. The old lady gasped, fluttering a hand over her mouth, and the girl gave a hard laugh. “That’s all there’s left of me!” she said.

People started filing into the square, hundreds and hundreds of them, taking their places amid the blooming forget-me-nots and sweetly trilling birds. They wielded axes, hatchets, clubs, knives, hammers, guns, stones. A black maid hurried to the square to collect her wandering charge, worried that the child might “catch something from them poor white folks.” A chorus of voices shouted “Bread or blood! Bread or blood!” a rolling drumbeat that matched the pace of their steps.

More rioters joined in, thousands of them now, punching their fists toward the sky, funneling through the alleys, charging into stores and grabbing everything they found, bread and turnips and hams and shoes, hoisting them into carts and wagons lined along the curb, where female getaway drivers waited in stern complicity. They smashed locked doors with their hatchets and hammers and stones, working with a terrible earnestness, looting both necessities and luxuries: bonnets, tools, cornmeal, piles of bacon, barrels of flour, strings of glinting jewels. One merchant rolled up his sleeves and stood guard at the door of his shop, waving a six-shooter, vowing to defend his property at the risk of his life. Another tossed out boxes of needles, hoping that would be enough to placate the crowd.

Within the hour the Public Guard filed up Seventeenth Street, Jefferson Davis close behind. The president clambered into a cart and looked out over the crowd, which fell instantly and utterly silent. In a mournful tone he urged the people to “abstain from their lawless acts” and wondered why they had stolen jewelry and finery when they claimed to be starving. No response. The president turned out his pockets and gathered a thin roll of Confederate graybacks in his fists.

“You say you are hungry and have no money,” he said. “Here is all I have; it is not much, but take it.”

“The Union!” the mob screamed. “No more starvation!”

He tossed the money and watched the people dive to catch it. “We do not desire to injure anyone, but this lawlessness must stop. I will give you five minutes to disperse. Otherwise you will be fired upon.”

The crowd murmured and rustled but stayed rooted in place.

“Captain Gay,” Davis intoned, “order your men to load with ball cartridges.”

“Load!” the captain shouted.

There was a swift clattering of ramrods as the soldiers obeyed, stuffing powder and balls down the muzzles of their muskets.

“Captain Gay,” he said again, “if this street is not cleared within five minutes, order your men to fire down the street until it is cleared.”

The president lifted his pocket watch into the air to count the tick of the hands.

All at once the rioters gave up. They broke off in pairs and threes, hatchets and clubs dangling by their sides, stones dropping to the ground, loot lying forgotten in the carts and strewn across sidewalks, broken glass crunching under their plain brown work shoes. Police tracked down and arrested forty-seven of them.

By nightfall all of Richmond seethed with suspicion, convinced that the “bread riot” was the work of Yankee spies. “This demonstration was made use of by the disaffected in our midst,” one resident declared, “for the misrepresentation and exaggeration of our real condition.” The city council ruled that whoever planned the riot had “devilish and secret motives,” and the War Department ordered newspapers to stifle coverage so that the Confederacy would not be further humiliated. The Richmond Examiner nevertheless condemned the rioters as “emissaries of the Federal Government” and found it “glaringly incongruous” that so many of the supposedly impoverished suspects were able to post bail and retain expensive counsel, paying as much as $500 cash—money supplied by Elizabeth and a few wealthy Unionist friends.

The Richmond Underground made sure news of the bread riot reached the Union army and the Northern press, along with personal updates about the Confederate president. The current year, in the words of Varina Davis, had opened “drearily” for her husband. He was still morose over the fall of numerous Southern cities in the western theater: Donelson, Tennessee (the battle that earned Ulysses S. Grant the nickname “Unconditional Surrender”); Nashville (whose citizens, the Northern press reported, were all “hard up”); and Memphis, where, said one correspondent, “secession had made havoc of all female charms and graces,” infecting women like a “contagious disease.” Davis’s health, always poor, was worsening by the day. He suffered from gastric distress, bouts of malaria, and constant inflammation in his left eye, which Varina treated with mercury drops. Chronic neuralgia left even his face in constant agony. Often he was too sick to walk the half mile to his official office near Capitol Square and instead worked at home, Mary Jane lingering with her duster, cleaning the adjacent children’s nursery until she could get to his desk. She was there after he penned a response to the bread riot, reprinted in the Yankee press, in which he appealed to Southerners to “respond to the call of patriotism” with continued sacrifice and prayer.

Most of Richmond’s prominent families responded, stripping their beds of blankets, sheets, and pillows; packing up the contents of their pantries; gathering coats and shoes; and sending everything off to Confederate soldiers. Some even offered their horses to replenish the army’s dwindling supply; thousands of mounts, on both sides, were lost to convalescent camps, where they recovered from battle fatigue and the equine equivalent of “soldier’s heart,” an early term for post-traumatic stress disorder. General Lee, in an April 16 letter to Davis, confided his anxiety over “the present immobility of the army, owing to the condition of our horses and the scarcity of forage and provisions.” Civilians who didn’t willingly contribute risked a visit from rebel “impressment agents,” charged with confiscating food, fuel, slaves, horses, and anything else the army might need. Elizabeth witnessed the agents seize horses from bread carts and unsuspecting peddlers arriving at the market. Most of the livery stables on Franklin and other streets had been completely swept of their steeds. Some residents, in anticipation of the coming agents, mounted diminutive slaves on their horses and sent them, under whip and spur, in the opposite direction.

The agents already had come to Elizabeth’s door three times, shaking papers from the War Department in her face and claiming they had the right to her horses. They did not pay her on the spot as they had been instructed to do. Three of her brilliant white horses were gone, never to be seen again, and she stashed her last remaining horse in the smokehouse. There she considered him safe until agents again made the rounds in her neighborhood, creeping behind the mansions and peering inside stables. One night, when all was clear, she rolled up her Oriental rugs and led her horse inside her home. She wrapped his hooves with rags and spread straw across the floor of her study.

She implored the horse to stay quiet, scratching his withers and sending her nieces with baskets of fresh apples to keep him company. To her amazement he stayed in the study for days at a time, until the officers gave up, never neighing or stomping loud enough to be heard. It was, she marveled, as though he “thoroughly understood matters”—that in the South’s “dear young Government” there was no safety for anyone, not even an innocent beast.