No matter how tightly she drew the curtains or how low she turned the gaslight, Elizabeth always feared that someone was watching, aware that even her simplest movements were not what they seemed. General Winder had left her home and Richmond for Andersonville, Georgia, but his detectives remained vigilant, especially since her brother John had finally been forced to the front lines and deserted during the Battle of Cold Harbor, escaping to Philadelphia to live with their sister Anna. His friends told the Richmond press and officials that he’d been captured and carried off by a Yankee raiding party, but rumors persisted that he’d fled north, and that “Beast” Butler had hired him as a spy. “Van Lew rode out from his friend’s in Hanover with a nigger in a buggy,” the Confederate police chief observed. “The nigger and the buggy came back, but Van Lew didn’t. It is damned strange if the Yankee raiders took Van Lew that they didn’t take the nigger and buggy, too.”

Elizabeth began varying her methods of delivering dispatches, both to throw off the detectives and to meet increased demand from Union officials. In one note she told them that her spying “puts me to a great disadvantage and I do not wish to do it unless it is received welcomely.” It was, especially with General Grant now in charge of the eastern theater, headquartered twenty miles south of Richmond. She mined her contacts in the Confederate government, deployed members of the Richmond Underground to gather information, and picked up Mary Jane’s reports from the seamstress, sitting in her study and interpreting each piece of information. Three days per week, after either encrypting her dispatches or writing them in invisible ink, she closed her fist around them and walked slowly, casually, to the ornamented iron fireplace at the far end of the room.

On either side of the fireplace grate stood two slender columns, each topped by a brass figurine of a lion preparing to pounce. She had loosened one of these so it could be raised like the lid of a mailbox. With her back to the mantel, she slipped the dispatches beneath the crouching lion and left the room; her part was finished. In a few moments one of the housemaids would enter and go about her work, seemingly intent on polishing each brass curve and mahogany spire, humming as she made her way to the lion and lifted the lid, tucking the letters down her homespun dress.

The maid took it from there, looping a basket around her arm and strolling down to Old Market Hall. She passed by the vegetable benches and butcher stalls, where ribbons of moist pink flesh dangled from strings; bacon was now $20 per pound, about $300 in today’s dollars and a 6,700 percent increase from before the war. She stopped at a cart where she recognized the merchants: two men, also Van Lew servants, who’d come from the family farm in Henrico County. The maid feigned interest in the contents of the cart, sifting through the pile of corn and potatoes and peas, picking a few pieces for her basket. Instead of money she paid with dispatches, which the servants discreetly plugged inside the soles of their shoes. The shoes were great strong brogans made by a Richmond cobbler working with the Underground, and he fashioned the soles so they were double and hollow, capable of holding letters and even maps. Shoes, like everything else, had become exorbitantly expensive—high-laced shoes cost $100, and a new pair of boots $225—but Elizabeth’s servants all had two pairs each and changed them every day, never wearing out of Richmond the same shoes they wore into the city each morning.

When the soles were filled to capacity, the men hollowed out an egg or a turnip, compressing the notes into slender scrolls and sliding them inside, hiding the dummy goods among the real thing. They departed after dusk, connecting with a Union scout at one of five Underground rendezvous points between Richmond and Grant’s headquarters at City Point, at the junction of the James and Appomattox Rivers. The servants’ preferred route was Charles City Road, which meandered southeast to the banks of the James, but if it was closed to civilian traffic they abandoned their carts and continued on foot, bushwhacking their way through thirty-five miles of woods, a journey of two days. Either way the guards passed them through the lines without question or incident; they were just slaves obeying orders, running errands for their mistress, not so much above suspicion as below it. Before daylight the Union scout, dispatches in hand, reported to headquarters, sometimes bringing along a Richmond newspaper and flowers from Elizabeth’s garden, still fresh when they arrived on the general’s breakfast table.

On the evening of September 27 an old family friend, Miss Lucy King, called at the mansion. She stood in the doorway, hands shielding her face, and whispered, “Do you think I am being watched?”

Elizabeth glanced left and right and hustled her inside.

Lucy told a story: one recent morning, while she lay in bed sick, her maid came to her room and said a detective was asking for her. She sent word she was ill. The detective returned the following day and left a handwritten message requesting her to report immediately to Eleventh and Broad Streets. Captain Thomas Walker Doswell, the new provost marshal, was seeking testimony against the Van Lew family, and her cooperation would be most appreciated.

Miss King felt she had no choice but to go.

Doswell pulled out a chair for her and smiled, the tip of his full brown beard grazing his cravat. He assured her she had nothing to fear. He, like his predecessor, General Winder, was well acquainted with the Van Lews. He had been a dinner guest in their home. He knew Elizabeth and her mother were upstanding Christian women, and he certainly did not want them to be lured into danger by the wrong sort of people, risking their lives for false and foolish ideals. Perhaps she was privy to information about the Van Lews? Information that, if they were on a wayward course, might help set them straight? He understood the “delicacy” of the situation, and promised that her name would not be mentioned to the Van Lews.

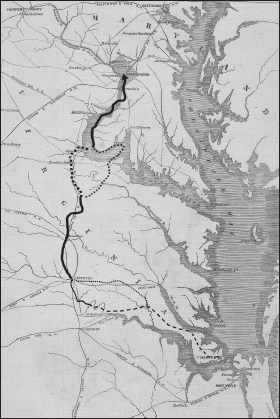

Routes of the Richmond Underground: first, seventy-five miles southeast to “Beast Butler” at Fort Monroe; and later, tweny miles southeast to Grant at City Point.

(Library of Virginia)

He leaned forward, waiting, lips pushing to maintain his smile.

“I am not with them as a spy,” Miss King responded.

Doswell let her go, suggesting she keep his words in mind.

Elizabeth was relieved her friend had not succumbed to the pressure, and hoped that the new provost marshal would give up.

He didn’t.

Next he sent detectives to interview various neighbors and associates. A neighbor had no direct knowledge of disloyalty but heard his sister damn the Van Lews as “good Yankees.” A businessman distinctly recalled Elizabeth saying, “I wish the Yankees would whip the Confederates.” The minister of the Third Presbyterian Church had heard Elizabeth praise the “violent and outrageous federal raiding parties.” A Richmond grocer remembered Elizabeth’s advice to “go to the Yankees and take the oath of allegiance.”

The detectives were particularly interested in this last bit of testimony, given Elizabeth’s brother John’s suspicious absence from his Confederate regiment. They had one last person on their list: John’s estranged wife, Mary, who surely harbored many incriminating secrets about the family, and who would be all too willing to share them.

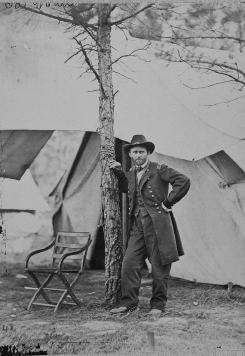

General Ulysses S. Grant at City Point, fall 1864.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)